11.3 Congressional Representation

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the basics of representation

- Describe the extent to which Congress as a body represents the U.S. population

- Explain the concept of collective representation

- Describe the forces that influence congressional approval ratings

The tension between local and national politics described in the previous section is essentially a struggle between interpretations of representation. Representation is a complex concept. It can mean paying careful attention to the concerns of constituents, understanding that representatives must act as they see fit based on what they feel best for the constituency, or relying on the particular ethnic, racial, or gender diversity of those in office. In this section, we will explore three different models of representation and the concept of descriptive representation. We will look at the way members of Congress navigate the challenging terrain of representation as they serve, and all the many predictable and unpredictable consequences of the decisions they make.

TYPES OF REPRESENTATION: LOOKING OUT FOR CONSTITUENTS

By definition and title, senators and House members are representatives. This means they are intended to be drawn from local populations around the country so they can speak for and make decisions for those local populations, their constituents, while serving in their respective legislative houses. That is, representation refers to an elected leader’s looking out for constituents while carrying out the duties of the office. 26

Theoretically, the process of constituents voting regularly and reaching out to their representatives helps these congresspersons better represent them. It is considered a given by some in representative democracies that representatives will seldom ignore the wishes of constituents, especially on salient issues that directly affect the district or state. In reality, the job of representing in Congress is often quite complicated, and elected leaders do not always know where their constituents stand. Nor do constituents always agree on everything. Navigating their sometimes contradictory demands and balancing them with the demands of the party, powerful interest groups, ideological concerns, the legislative body, their own personal beliefs, and the country as a whole can be a complicated and frustrating process for representatives.

Traditionally, representatives have seen their role as that of a delegate, a trustee, or someone attempting to balance the two. Representatives who see themselves as delegates believe they are empowered merely to enact the wishes of constituents. Delegates must employ some means to identify the views of their constituents and then vote accordingly. They are not permitted the liberty of employing their own reason and judgment while acting as representatives in Congress. This is the delegate model of representation .

In contrast, a representative who understands their role to be that of a trustee believes they are entrusted by the constituents with the power to use good judgment to make decisions on the constituents’ behalf. In the words of the eighteenth-century British philosopher Edmund Burke, who championed the trustee model of representation , “Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests . . . [it is rather] a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole.” 27 In the modern setting, trustee representatives will look to party consensus, party leadership, powerful interests, the member’s own personal views, and national trends to better identify the voting choices they should make.

Understandably, few if any representatives adhere strictly to one model or the other. Instead, most find themselves attempting to balance the important principles embedded in each. Political scientists call this the politico model of representation . In it, members of Congress act as either trustee or delegate based on rational political calculations about who is best served, the constituency or the nation.

For example, every representative, regardless of party or conservative versus liberal leanings, must remain firm in support of some ideologies and resistant to others. On the political right, an issue that demands support might be gun rights; on the left, it might be a woman’s right to an abortion. For votes related to such issues, representatives will likely pursue a delegate approach. For other issues, especially complex questions the public at large has little patience for, such as subtle economic reforms, representatives will tend to follow a trustee approach. This is not to say their decisions on these issues run contrary to public opinion. Rather, it merely means they are not acutely aware of or cannot adequately measure the extent to which their constituents support or reject the proposals at hand. It could also mean that the issue is not salient to their constituents. Congress works on hundreds of different issues each year, and constituents are likely not aware of the particulars of most of them.

DESCRIPTIVE REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS

In some cases, representation can seem to have very little to do with the substantive issues representatives in Congress tend to debate. Instead, proper representation for some is rooted in the racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, gender, and sexual identity of the representatives themselves. This form of representation is called descriptive representation .

At one time, there was relatively little concern about descriptive representation in Congress. A major reason is that until well into the twentieth century, White men of European background constituted an overwhelming majority of the voting population. African Americans were routinely deprived of the opportunity to participate in democracy, and Hispanics and other minority groups were fairly insignificant in number and excluded by the states. While women in many western states could vote sooner, all women were not able to exercise their right to vote nationwide until passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, and they began to make up more than 5 percent of either chamber only in the 1990s.

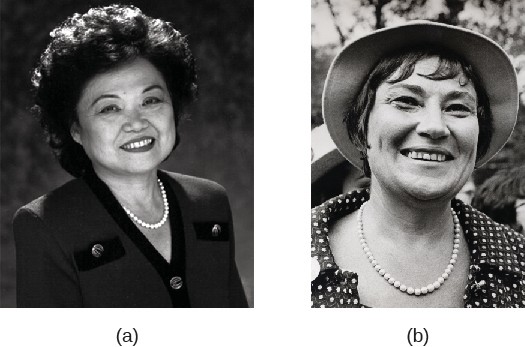

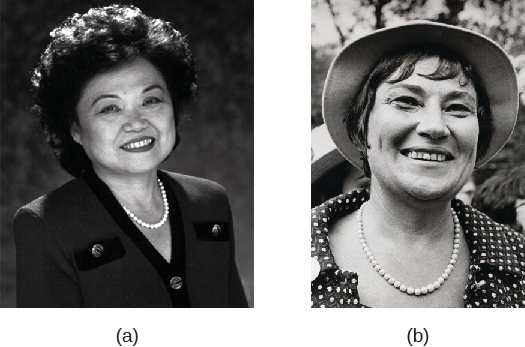

Many advances in women’s rights have been the result of women’s greater engagement in politics and representation in the halls of government, especially since the founding of the National Organization for Women in 1966 and the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) in 1971. The NWPC was formed by Bella Abzug ( Figure 11.11 ), Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and other leading feminists to encourage women’s participation in political parties, elect women to office, and raise money for their campaigns. For example, Patsy Mink (D-HI) ( Figure 11.11 ), the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, was the coauthor of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX of which prohibits sex discrimination in education. Mink had been interested in fighting discrimination in education since her youth, when she opposed racial segregation in campus housing while a student at the University of Nebraska. She went to law school after being denied admission to medical school because of her gender. Like Mink, many other women sought and won political office, many with the help of the NWPC. Today, EMILY’s List, a PAC founded in 1985 to help elect pro-choice Democratic women to office, plays a major role in fundraising for female candidates. In the 2018 midterm elections, thirty-four women endorsed by EMILY's List won election to the U.S. House. 28 In 2020, the Republicans took a page from the Democrats' playbook when they made the recruitment and support of quality female candidates a priority and increased the number of Republican women in the House from thirteen to twenty-eight, including ten seats formerly held by Democrats. 29

In the wake of the Civil Rights Movement , African American representatives also began to enter Congress in increasing numbers. In 1971, to better represent their interests, these representatives founded the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), an organization that grew out of a Democratic select committee formed in 1969. Founding members of the CBC include Ralph Metcalfe (D-IL), a former sprinter from Chicago who had medaled at both the Los Angeles (1932) and Berlin (1936) Olympic Games, and Shirley Chisholm, a founder of the NWPC and the first African American woman to be elected to the House of Representatives ( Figure 11.12 ).

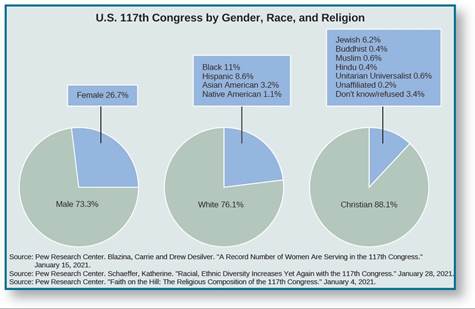

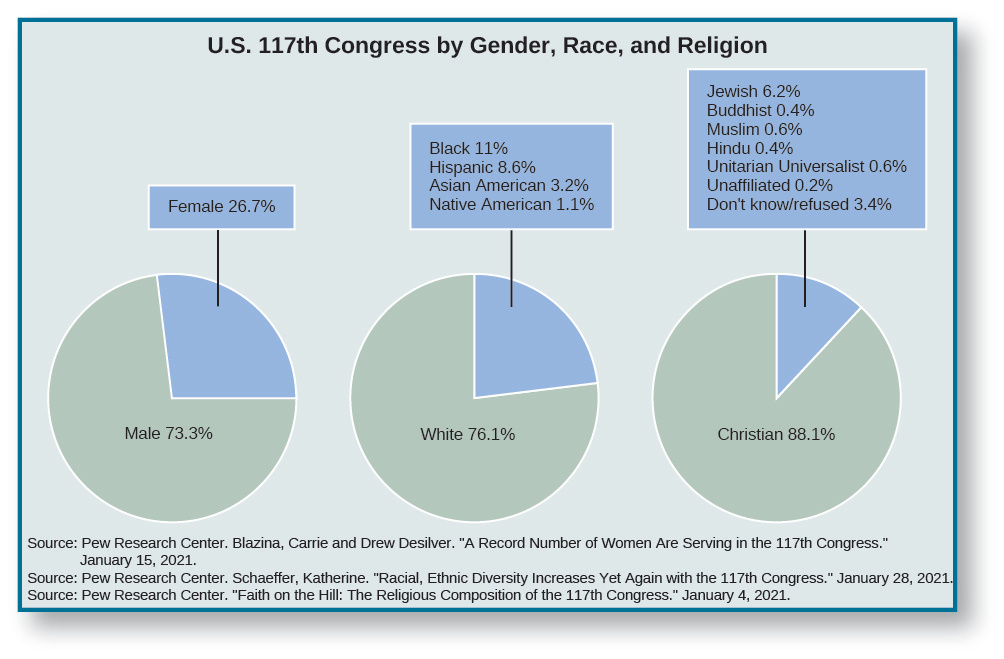

In recent decades, Congress has become much more descriptively representative of the United States. The 117th Congress, which began in January 2021 had a historically large percentage of racial and ethnic minorities. African Americans made up the largest percentage, with sixty-two members (including two delegates and two people who would soon resign to serve in the executive branch), while Latinos accounted for fifty-four members (including two delegates and the Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico), up from thirty just a decade before. 30 Yet, demographically speaking, Congress as a whole is still a long way from where the country is and is composed of largely White wealthy men. For example, although more than half the U.S. population is female, only 25 percent of Congress is. Congress is also overwhelmingly Christian ( Figure 11.13 ).

REPRESENTING CONSTITUENTS

Ethnic, racial, gender, or ideological identity aside, it is a representative’s actions in Congress that ultimately reflect their understanding of representation. Congress members’ most important function as lawmakers is writing, supporting, and passing bills. And as representatives of their constituents, they are charged with addressing those constituents’ interests. Historically, this job has included what some have affectionately called “bringing home the bacon” but what many (usually those outside the district in question) call pork-barrel politics . As a term and a practice, pork-barrel politics—federal spending on projects designed to benefit a particular district or set of constituents—has been around since the nineteenth century, when barrels of salt pork were both a sign of wealth and a system of reward. While pork-barrel politics are often deplored during election campaigns, and earmarks—funds appropriated for specific projects—are no longer permitted in Congress (see feature box below), legislative control of local appropriations nevertheless still exists. In more formal language, allocation , or the influencing of the national budget in ways that help the district or state, can mean securing funds for a specific district’s project like an airport, or getting tax breaks for certain types of agriculture or manufacturing.

Get Connected!

Language and metaphor.

The language and metaphors of war and violence are common in politics. Candidates routinely “smell blood in the water,” “battle for delegates,” go “head-to-head,” and “make heads roll.” But references to actual violence aren’t the only metaphorical devices commonly used in politics. Another is mentions of food. Powerful speakers frequently “throw red meat to the crowds”; careful politicians prefer to stick to “meat-and-potato issues”; and representatives are frequently encouraged by their constituents to “bring home the bacon.” And the way members of Congress typically “bring home the bacon” is often described with another agricultural metaphor, the “earmark.”

In ranching, an earmark is a small cut on the ear of a cow or other animal to denote ownership. Similarly, in Congress, an earmark is a mark in a bill that directs some of the bill’s funds to be spent on specific projects or for specific tax exemptions. Since the 1980s, the earmark has become a common vehicle for sending money to various projects around the country. Many a road, hospital, and airport can trace its origins back to a few skillfully drafted earmarks.

Relatively few people outside Congress had ever heard of the term before the 2008 presidential election, when Republican nominee Senator John McCain touted his career-long refusal to use the earmark as a testament to his commitment to reforming spending habits in Washington. 31 McCain’s criticism of the earmark as a form of corruption cast a shadow over a previously common legislative practice. As the country sank into recession and Congress tried to use spending bills to stimulate the economy, the public grew more acutely aware of its earmarking habits. Congresspersons then were eager to distance themselves from the practice. In fact, the use of earmarks to encourage Republicans to help pass health care reform actually made the bill less popular with the public.

In 2011, after Republicans took over the House, they outlawed earmarks. But with deadlocks and stalemates becoming more common, some quiet voices have begun asking for a return to the practice. They argue that Congress works because representatives can satisfy their responsibilities to their constituents by making deals. The earmarks are those deals. By taking them away, Congress has hampered its own ability to “bring home the bacon.”

Are earmarks a vital part of legislating or a corrupt practice that was rightly jettisoned? Pick a cause or industry, and investigate whether any earmarks ever favored it, or research the way earmarks have hurt or helped your state or district, and decide for yourself.

Follow-up activity: Find out where your congressional representative stands on the ban on earmarks and write to support or dissuade them.

Such budgetary allocations aren’t always looked upon favorably by constituents. Consider, for example, the passage of the ACA in 2010. The desire for comprehensive universal health care had been a driving position of the Democrats since at least the 1960s. During the 2008 campaign, that desire was so great among both Democrats and Republicans that both parties put forth plans. When the Democrats took control of Congress and the presidency in 2009, they quickly began putting together their plan. Soon, however, the politics grew complex, and the proposed plan became very contentious for the Republican Party.

Nevertheless, the desire to make good on a decades-old political promise compelled Democrats to do everything in their power to pass something. They offered sympathetic members of the Republican Party valuable budgetary concessions; they attempted to include allocations they hoped the opposition might feel compelled to support; and they drafted the bill in a purposely complex manner to avoid future challenges. These efforts, however, had the opposite effect. The Republican Party’s constituency interpreted the allocations as bribery and the bill as inherently flawed, and felt it should be scrapped entirely. The more Democrats dug in, the more frustrated the Republicans became ( Figure 11.14 ).

The Republican opposition, which took control of the House during the 2010 midterm elections, promised constituents they would repeal the law. Their attempts were complicated, however, by the fact that Democrats still held the Senate and the presidency. Yet, the desire to represent the interests of their constituents compelled Republicans to use another tool at their disposal, the symbolic vote. During the 112th and 113th Congresses, Republicans voted more than sixty times to either repeal or severely limit the reach of the law. They understood these efforts had little to no chance of ever making it to the president’s desk. And if they did, he would certainly have vetoed them. But it was important for these representatives to demonstrate to their constituents that they understood their wishes and were willing to act on them.

Historically, representatives have been able to balance their role as members of a national legislative body with their role as representatives of a smaller community. The Obamacare fight, however, gave a boost to the growing concern that the power structure in Washington divides representatives from the needs of their constituency. 32 This has exerted pressure on representatives to the extent that some now pursue a more straightforward delegate approach to representation. Indeed, following the 2010 election, a handful of Republicans began living in their offices in Washington, convinced that by not establishing a residence in Washington, they would appear closer to their constituents at home. 33

COLLECTIVE REPRESENTATION AND CONGRESSIONAL APPROVAL

The concept of collective representation describes the relationship between Congress and the United States as a whole. That is, it considers whether the institution itself represents the American people, not just whether a particular member of Congress represents their district. Predictably, it is far more difficult for Congress to maintain a level of collective representation than it is for individual members of Congress to represent their own constituents. Not only is Congress a mixture of different ideologies, interests, and party affiliations, but the collective constituency of the United States has an even-greater level of diversity. Nor is it a solution to attempt to match the diversity of opinions and interests in the United States with those in Congress. Indeed, such an attempt would likely make it more difficult for Congress to maintain collective representation. Its rules and procedures require Congress to use flexibility, bargaining, and concessions. Yet, it is this flexibility and these concessions, which many now interpret as corruption, that tend to engender the high public disapproval ratings experienced by Congress.

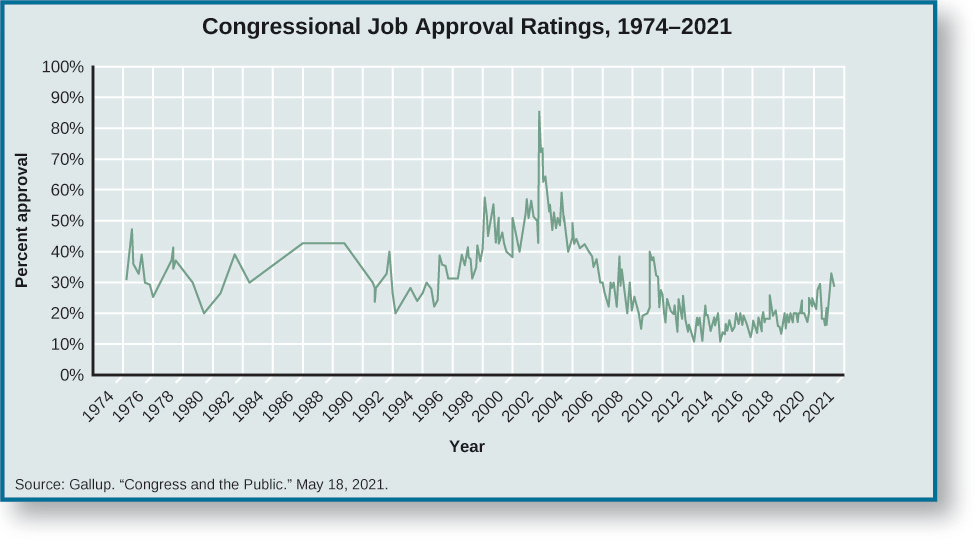

After many years of deadlocks and bickering on Capitol Hill, the national perception of Congress has tended to run under 20 percent approval in recent years, with large majorities disapproving. Through mid-2021, the Congress, narrowly under Democratic control, was receiving higher approval ratings, above 30 percent. However, congressional approval still lags public approval of the presidency and Supreme Court by a considerable margin. In the two decades following the Watergate scandal in the early 1970s, the national approval rating of Congress hovered between 30 and 40 percent, then trended upward in the 1990s, before trending downward in the twenty-first century. 34

Yet, incumbent reelections have remained largely unaffected. The reason has to do with the remarkable ability of many in the United States to separate their distaste for Congress from their appreciation for their own representative. Paradoxically, this tendency to hate the group but love one’s own representative actually perpetuates the problem of poor congressional approval ratings. The reason is that it blunts voters’ natural desire to replace those in power who are earning such low approval ratings.

As decades of polling indicate, few events push congressional approval ratings above 50 percent. Indeed, when the ratings are graphed, the two noticeable peaks are at 57 percent in 1998 and 84 percent in 2001 ( Figure 11.15 ). In 1998, according to Gallup polling, the rise in approval accompanied a similar rise in other mood measures, including President Bill Clinton ’s approval ratings and general satisfaction with the state of the country and the economy. In 2001, approval spiked after the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Bush administration launched the "War on Terror," sending troops first to Afghanistan and later to Iraq. War has the power to bring majorities of voters to view their Congress and president in an overwhelmingly positive way. 35

Nevertheless, all things being equal, citizens tend to rate Congress more highly when things get done and more poorly when things do not get done. For example, during the first half of President Obama’s first term, Congress’s approval rating reached a relative high of about 40 percent. Both houses were dominated by members of the president’s own party, and many people were eager for Congress to take action to end the deep recession and begin to repair the economy. Millions were suffering economically, out of work, or losing their jobs, and the idea that Congress was busy passing large stimulus packages, working on finance reform, and grilling unpopular bank CEOs and financial titans appealed to many. Approval began to fade as the Republican Party slowed the wheels of Congress during the tumultuous debates over Obamacare and reached a low of 9 percent following the federal government shutdown in October 2013.

One of the events that began the approval rating’s downward trend was Congress’s divisive debate over national deficits. A deficit is what results when Congress spends more than it has available. It then conducts additional deficit spending by increasing the national debt. Many modern economists contend that during periods of economic decline, the nation should run deficits, because additional government spending has a stimulative effect that can help restart a sluggish economy. Despite this benefit, voters rarely appreciate deficits. They see Congress as spending wastefully during a time when they themselves are cutting costs to get by.

The disconnect between the common public perception of running a deficit and its legitimate policy goals is frequently exploited for political advantage. For example, while running for the presidency in 2008, Barack Obama slammed the deficit spending of the George W. Bush presidency, saying it was “unpatriotic.” This sentiment echoed complaints Democrats had been issuing for years as a weapon against President Bush’s policies. Following the election of President Obama and the Democratic takeover of the Senate, the concern over deficit spending shifted parties, with Republicans championing a spendthrift policy as a way of resisting Democratic policies.

Link to Learning

Find your representative at the U.S. House website and then explore their website and social media accounts to see whether the issues on which your representative spends time are the ones you think are most appropriate.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Glen Krutz, Sylvie Waskiewicz, PhD

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: American Government 3e

- Publication date: Jul 28, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/11-3-congressional-representation

© Jul 18, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

12.3 Congressional Representation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the basics of representation

- Describe the extent to which Congress as a body represents the U.S. population

- Explain the concept of collective representation

- Describe the forces that influence congressional approval ratings

The tension between local and national politics described in the previous section is essentially a struggle between interpretations of representation. Representation is a complex concept. It can mean paying careful attention to the concerns of constituents, understanding that representatives must act as they see fit based on what they feel best for the constituency, or relying on the particular ethnic, racial, or gender diversity of those in office. In this section, we will explore three different models of representation and the concept of descriptive representation. We will look at the way members of Congress navigate the challenging terrain of representation as they serve, and all the many predictable and unpredictable consequences of the decisions they make.

TYPES OF REPRESENTATION: LOOKING OUT FOR CONSTITUENTS

By definition and title, senators and House members are representatives. This means they are intended to be drawn from local populations around the country so they can speak for and make decisions for those local populations, their constituents, while serving in their respective legislative houses. That is, representation refers to an elected leader’s looking out for constituents while carrying out the duties of the office. 26

Theoretically, the process of constituents voting regularly and reaching out to their representatives helps these congresspersons better represent them. It is considered a given by some in representative democracies that representatives will seldom ignore the wishes of constituents, especially on salient issues that directly affect the district or state. In reality, the job of representing in Congress is often quite complicated, and elected leaders do not always know where their constituents stand. Nor do constituents always agree on everything. Navigating their sometimes contradictory demands and balancing them with the demands of the party, powerful interest groups, ideological concerns, the legislative body, their own personal beliefs, and the country as a whole can be a complicated and frustrating process for representatives.

Traditionally, representatives have seen their role as that of a delegate, a trustee, or someone attempting to balance the two. Representatives who see themselves as delegates believe they are empowered merely to enact the wishes of constituents. Delegates must employ some means to identify the views of their constituents and then vote accordingly. They are not permitted the liberty of employing their own reason and judgment while acting as representatives in Congress. This is the delegate model of representation .

In contrast, a representative who understands their role to be that of a trustee believes they are entrusted by the constituents with the power to use good judgment to make decisions on the constituents’ behalf. In the words of the eighteenth-century British philosopher Edmund Burke, who championed the trustee model of representation , “Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests . . . [it is rather] a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole.” 27 In the modern setting, trustee representatives will look to party consensus, party leadership, powerful interests, the member’s own personal views, and national trends to better identify the voting choices they should make.

Understandably, few if any representatives adhere strictly to one model or the other. Instead, most find themselves attempting to balance the important principles embedded in each. Political scientists call this the politico model of representation . In it, members of Congress act as either trustee or delegate based on rational political calculations about who is best served, the constituency or the nation.

For example, every representative, regardless of party or conservative versus liberal leanings, must remain firm in support of some ideologies and resistant to others. On the political right, an issue that demands support might be gun rights; on the left, it might be a woman’s right to an abortion. For votes related to such issues, representatives will likely pursue a delegate approach. For other issues, especially complex questions the public at large has little patience for, such as subtle economic reforms, representatives will tend to follow a trustee approach. This is not to say their decisions on these issues run contrary to public opinion. Rather, it merely means they are not acutely aware of or cannot adequately measure the extent to which their constituents support or reject the proposals at hand. It could also mean that the issue is not salient to their constituents. Congress works on hundreds of different issues each year, and constituents are likely not aware of the particulars of most of them.

DESCRIPTIVE REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS

In some cases, representation can seem to have very little to do with the substantive issues representatives in Congress tend to debate. Instead, proper representation for some is rooted in the racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, gender, and sexual identity of the representatives themselves. This form of representation is called descriptive representation .

At one time, there was relatively little concern about descriptive representation in Congress. A major reason is that until well into the twentieth century, White men of European background constituted an overwhelming majority of the voting population. African Americans were routinely deprived of the opportunity to participate in democracy, and Hispanics and other minority groups were fairly insignificant in number and excluded by the states. While women in many western states could vote sooner, all women were not able to exercise their right to vote nationwide until passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, and they began to make up more than 5 percent of either chamber only in the 1990s.

Many advances in women’s rights have been the result of women’s greater engagement in politics and representation in the halls of government, especially since the founding of the National Organization for Women in 1966 and the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) in 1971. The NWPC was formed by Bella Abzug ( Figure 11.11 ), Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and other leading feminists to encourage women’s participation in political parties, elect women to office, and raise money for their campaigns. For example, Patsy Mink (D-HI) ( Figure 11.11 ), the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, was the coauthor of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX of which prohibits sex discrimination in education. Mink had been interested in fighting discrimination in education since her youth, when she opposed racial segregation in campus housing while a student at the University of Nebraska. She went to law school after being denied admission to medical school because of her gender. Like Mink, many other women sought and won political office, many with the help of the NWPC. Today, EMILY’s List, a PAC founded in 1985 to help elect pro-choice Democratic women to office, plays a major role in fundraising for female candidates. In the 2018 midterm elections, thirty-four women endorsed by EMILY’s List won election to the U.S. House. 28 In 2020, the Republicans took a page from the Democrats’ playbook when they made the recruitment and support of quality female candidates a priority and increased the number of Republican women in the House from thirteen to twenty-eight, including ten seats formerly held by Democrats. 29

REPRESENTING CONSTITUENTS

Ethnic, racial, gender, or ideological identity aside, it is a representative’s actions in Congress that ultimately reflect their understanding of representation. Congress members’ most important function as lawmakers is writing, supporting, and passing bills. And as representatives of their constituents, they are charged with addressing those constituents’ interests. Historically, this job has included what some have affectionately called “bringing home the bacon” but what many (usually those outside the district in question) call pork-barrel politics . As a term and a practice, pork-barrel politics —federal spending on projects designed to benefit a particular district or set of constituents—has been around since the nineteenth century, when barrels of salt pork were both a sign of wealth and a system of reward. While pork-barrel politics are often deplored during election campaigns, and earmarks—funds appropriated for specific projects—are no longer permitted in Congress (see feature box below), legislative control of local appropriations nevertheless still exists. In more formal language, allocation , or the influencing of the national budget in ways that help the district or state, can mean securing funds for a specific district’s project like an airport, or getting tax breaks for certain types of agriculture or manufacturing.

Such budgetary allocations aren’t always looked upon favorably by constituents. Consider, for example, the passage of the ACA in 2010. The desire for comprehensive universal health care had been a driving position of the Democrats since at least the 1960s. During the 2008 campaign, that desire was so great among both Democrats and Republicans that both parties put forth plans. When the Democrats took control of Congress and the presidency in 2009, they quickly began putting together their plan. Soon, however, the politics grew complex, and the proposed plan became very contentious for the Republican Party.

Nevertheless, the desire to make good on a decades-old political promise compelled Democrats to do everything in their power to pass something. They offered sympathetic members of the Republican Party valuable budgetary concessions; they attempted to include allocations they hoped the opposition might feel compelled to support; and they drafted the bill in a purposely complex manner to avoid future challenges. These efforts, however, had the opposite effect. The Republican Party’s constituency interpreted the allocations as bribery and the bill as inherently flawed, and felt it should be scrapped entirely. The more Democrats dug in, the more frustrated the Republicans became ( Figure 11.14 ).

Historically, representatives have been able to balance their role as members of a national legislative body with their role as representatives of a smaller community. The Obamacare fight, however, gave a boost to the growing concern that the power structure in Washington divides representatives from the needs of their constituency. 32 This has exerted pressure on representatives to the extent that some now pursue a more straightforward delegate approach to representation. Indeed, following the 2010 election, a handful of Republicans began living in their offices in Washington, convinced that by not establishing a residence in Washington, they would appear closer to their constituents at home. 33

COLLECTIVE REPRESENTATION AND CONGRESSIONAL APPROVAL

The concept of collective representation describes the relationship between Congress and the United States as a whole. That is, it considers whether the institution itself represents the American people, not just whether a particular member of Congress represents their district. Predictably, it is far more difficult for Congress to maintain a level of collective representation than it is for individual members of Congress to represent their own constituents. Not only is Congress a mixture of different ideologies, interests, and party affiliations, but the collective constituency of the United States has an even-greater level of diversity. Nor is it a solution to attempt to match the diversity of opinions and interests in the United States with those in Congress. Indeed, such an attempt would likely make it more difficult for Congress to maintain collective representation. Its rules and procedures require Congress to use flexibility, bargaining, and concessions. Yet, it is this flexibility and these concessions, which many now interpret as corruption, that tend to engender the high public disapproval ratings experienced by Congress.

After many years of deadlocks and bickering on Capitol Hill, the national perception of Congress has tended to run under 20 percent approval in recent years, with large majorities disapproving. Through mid-2021, the Congress, narrowly under Democratic control, was receiving higher approval ratings, above 30 percent. However, congressional approval still lags public approval of the presidency and Supreme Court by a considerable margin. In the two decades following the Watergate scandal in the early 1970s, the national approval rating of Congress hovered between 30 and 40 percent, then trended upward in the 1990s, before trending downward in the twenty-first century. 34

Yet, incumbent reelections have remained largely unaffected. The reason has to do with the remarkable ability of many in the United States to separate their distaste for Congress from their appreciation for their own representative. Paradoxically, this tendency to hate the group but love one’s own representative actually perpetuates the problem of poor congressional approval ratings. The reason is that it blunts voters’ natural desire to replace those in power who are earning such low approval ratings.

As decades of polling indicate, few events push congressional approval ratings above 50 percent. Indeed, when the ratings are graphed, the two noticeable peaks are at 57 percent in 1998 and 84 percent in 2001 ( Figure 11.15 ). In 1998, according to Gallup polling, the rise in approval accompanied a similar rise in other mood measures, including President Bill Clinton ’s approval ratings and general satisfaction with the state of the country and the economy. In 2001, approval spiked after the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Bush administration launched the “War on Terror,” sending troops first to Afghanistan and later to Iraq. War has the power to bring majorities of voters to view their Congress and president in an overwhelmingly positive way. 35

One of the events that began the approval rating’s downward trend was Congress’s divisive debate over national deficits. A deficit is what results when Congress spends more than it has available. It then conducts additional deficit spending by increasing the national debt. Many modern economists contend that during periods of economic decline, the nation should run deficits, because additional government spending has a stimulative effect that can help restart a sluggish economy. Despite this benefit, voters rarely appreciate deficits. They see Congress as spending wastefully during a time when they themselves are cutting costs to get by.

The disconnect between the common public perception of running a deficit and its legitimate policy goals is frequently exploited for political advantage. For example, while running for the presidency in 2008, Barack Obama slammed the deficit spending of the George W. Bush presidency, saying it was “unpatriotic.” This sentiment echoed complaints Democrats had been issuing for years as a weapon against President Bush’s policies. Following the election of President Obama and the Democratic takeover of the Senate, the concern over deficit spending shifted parties, with Republicans championing a spendthrift policy as a way of resisting Democratic policies.

American Government and Politics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Congressional Representation

Lumen Learning and OpenStax

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the basics of representation

- Describe the extent to which Congress as a body represents the U.S. population

- Explain the concept of collective representation

- Describe the forces that influence congressional approval ratings

The tension between local and national politics described in the previous section is essentially a struggle between interpretations of representation. Representation is a complex concept. It can mean paying careful attention to the concerns of constituents, understanding that representatives must act as they see fit based on what they feel best for the constituency, or relying on the particular ethnic, racial, or gender diversity of those in office. In this section, we will explore three different models of representation and the concept of descriptive representation. We will look at the way members of Congress navigate the challenging terrain of representation as they serve and all the many predictable and unpredictable consequences of the decisions they make.

TYPES OF REPRESENTATION: LOOKING OUT FOR CONSTITUENTS

By definition and title, senators and House members are representatives. This means they are intended to be drawn from local populations around the country so they can speak for and make decisions for those local populations, their constituents, while serving in their respective legislative houses. That is, representation refers to an elected leader looking out for his or her constituents while carrying out the duties of the office. [1]

Theoretically, the process of constituents voting regularly and reaching out to their representatives helps these congresspersons better represent them. It is considered a given by some in representative democracies that representatives will seldom ignore the wishes of constituents, especially on salient issues that directly affect the district or state. In reality, the job of representing in Congress is often quite complicated, and elected leaders do not always know where their constituents stand. Nor do constituents always agree on everything. Navigating their sometimes contradictory demands and balancing them with the demands of the party, powerful interest groups, ideological concerns, the legislative body, their own personal beliefs, and the country as a whole can be a complicated and frustrating process for representatives.

Traditionally, representatives have seen their roles as that of delegates, trustees, or people attempting to balance the two. A representative who sees themselves as a delegate believes they are empowered merely to enact the wishes of constituents. Delegates must employ some means to identify the views of their constituents and then vote accordingly. They are not permitted the liberty of employing their own reason and judgment while acting as representatives in Congress. This is the delegate model of representation .

In contrast, a representative who understands their role to be that of a trustee believes they are entrusted by the constituents with the power to use good judgment to make decisions on the constituents’ behalf. In the words of the eighteenth-century British philosopher Edmund Burke, who championed the trustee model of representation , “Parliament is not a congress of ambassadors from different and hostile interests . . . [it is rather] a deliberative assembly of one nation, with one interest, that of the whole.” [2] In the modern setting, trustee representatives will look to party consensus, party leadership, powerful interests, the member’s own personal views, and national trends to better identify the voting choices they should make.

Understandably, few if any representatives adhere strictly to one model or the other. Instead, most find themselves attempting to balance the important principles embedded in each. Political scientists call this the politico model of representation . In it, a member of Congress acts as either trustee or delegate based on rational political calculations about who is best served, the constituency or the nation.

For example, every representative, regardless of party or conservative versus liberal leanings, must remain firm in support of some ideologies and resistant to others. On the political right, an issue that demands support might be gun rights; on the left, it might be a woman’s right to an abortion. For votes related to such issues, representatives will likely pursue a delegate approach. For other issues, especially complex questions the public at large has little patience for, such as subtle economic reforms, representatives will tend to follow a trustee approach. This is not to say their decisions on these issues run contrary to public opinion. Rather, it merely means they are not acutely aware of or cannot adequately measure the extent to which their constituents support or reject the proposals at hand. It could also mean that the issue is not salient to their constituents. Congress works on hundreds of different issues each year, and constituents are likely not aware of the particulars of most of them.

DESCRIPTIVE REPRESENTATION IN CONGRESS

In some cases, representation can seem to have very little to do with the substantive issues representatives in Congress tend to debate. Instead, proper representation for some is rooted in the racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, gender, and sexual identity of the representatives themselves. This form of representation is called descriptive representation .

At one time, there was relatively little concern about descriptive representation in Congress. A major reason is that until well into the twentieth century, White men of European background constituted an overwhelming majority of the voting population. African Americans were routinely deprived of the opportunity to participate in democracy, and Hispanics and other minority groups were fairly insignificant in number and excluded by the states. While women in many western states could vote sooner, all women were not able to exercise their right to vote nationwide until passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, and they began to make up more than 5 percent of either chamber only in the 1990s.

Many advances in women’s rights have been the result of women’s greater engagement in politics and representation in the halls of government, especially since the founding of the National Organization for Women in 1966 and the National Women’s Political Caucus (NWPC) in 1971. The NWPC was formed by Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Shirley Chisholm, and other leading feminists to encourage women’s participation in political parties, elect women to office, and raise money for their campaigns. For example, Patsy Mink (D-HI), the first Asian American woman elected to Congress, was the coauthor of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination in education. Mink had been interested in fighting discrimination in education since her youth, when she opposed racial segregation in campus housing while a student at the University of Nebraska. She went to law school after being denied admission to medical school because of her gender. Like Mink, many other women sought and won political office, many with the help of the NWPC. Today, EMILY’s List, a PAC founded in 1985 to help elect pro-choice Democratic women to office, plays a major role in fundraising for female candidates. In the 2018 midterm elections, thirty-four women endorsed by EMILY’s List won election to the U.S. House. [3] In 2020, the Republicans took a page from the Democrats’ playbook when they made the recruitment and support of quality female candidates a priority and increased the number of Republican women in the House from thirteen to twenty-eight, including ten seats formerly held by Democrats. [4]

In the wake of the civil rights movement, African American representatives also began to enter Congress in increasing numbers. In 1971, to better represent their interests, these representatives founded the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), an organization that grew out of a Democratic select committee formed in 1969. Founding members of the CBC include Ralph Metcalfe (D-IL), a former sprinter from Chicago who had medaled at both the Los Angeles (1932) and Berlin (1936) Olympic Games, and Shirley Chisholm, a founder of the NWPC and the first African American woman to be elected to the House of Representatives.

In recent decades, Congress has become much more descriptively representative of the United States. The 117th Congress, which began in January 2021, had a historically large percentage of racial and ethnic minorities. African Americans made up the largest percentage, with sixty-two members (including two delegates and two people who would soon resign to serve in the executive branch), while Latinos accounted for fifty-four members (including two delegates and the Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico), up from thirty just a decade before. [5] Yet, demographically speaking, Congress as a whole is still a long way from where the country is and is composed of largely White wealthy men. For example, although more than half the U.S. population is female, only 25 percent of Congress is. Congress is also overwhelmingly Christian.

REPRESENTING CONSTITUENTS

Ethnic, racial, gender, or ideological identity aside, it is a representative’s actions in Congress that ultimately reflect his or her understanding of representation. Congress members’ most important function as lawmakers is writing, supporting, and passing bills. And as representatives of their constituents, they are charged with addressing those constituents’ interests. Historically, this job has included what some have affectionately called “bringing home the bacon” but what many (usually those outside the district in question) call pork-barrel politics . As a term and a practice, pork-barrel politics—federal spending on projects designed to benefit a particular district or set of constituents—has been around since the nineteenth century, when barrels of salt pork were both a sign of wealth and a system of reward. While pork-barrel politics are often deplored during election campaigns, and earmarks—funds appropriated for specific projects—are no longer permitted in Congress (see feature box below), legislative control of local appropriations nevertheless still exists. In more formal language, allocation , or the influencing of the national budget in ways that help the district or state, can mean securing funds for a specific district’s project like an airport, or getting tax breaks for certain types of agriculture or manufacturing.

GET CONNECTED!

Language and Metaphor

The language and metaphors of war and violence are common in politics. Candidates routinely “smell blood in the water,” “battle for delegates,” go “head-to-head,” and “make heads roll.” But references to actual violence aren’t the only metaphorical devices commonly used in politics. Another is mentions of food. Powerful speakers frequently “throw red meat to the crowds;” careful politicians prefer to stick to “meat-and-potato issues;” and representatives are frequently encouraged by their constituents to “bring home the bacon.” And the way members of Congress typically “bring home the bacon” is often described with another agricultural metaphor, the “earmark.”

In ranching, an earmark is a small cut on the ear of a cow or other animal to denote ownership. Similarly, in Congress, an earmark is a mark in a bill that directs some of the bill’s funds to be spent on specific projects or for specific tax exemptions. Since the 1980s, the earmark has become a common vehicle for sending money to various projects around the country. Many a road, hospital, and airport can trace its origins back to a few skillfully drafted earmarks.

Relatively few people outside Congress had ever heard of the term before the 2008 presidential election, when Republican nominee Senator John McCain touted his career-long refusal to use the earmark as a testament to his commitment to reforming spending habits in Washington. [6] McCain’s criticism of the earmark as a form of corruption cast a shadow over a previously common legislative practice. As the country sank into recession and Congress tried to use spending bills to stimulate the economy, the public grew more acutely aware of its earmarking habits. Congresspersons then were eager to distance themselves from the practice. In fact, the use of earmarks to encourage Republicans to help pass health care reform actually made the bill less popular with the public.

In 2011, after Republicans took over the House, they outlawed earmarks. But with deadlocks and stalemates becoming more common, some quiet voices have begun asking for a return to the practice. They argue that Congress works because representatives can satisfy their responsibilities to their constituents by making deals. The earmarks are those deals. By taking them away, Congress has hampered its own ability to “bring home the bacon.”

Are earmarks a vital part of legislating or a corrupt practice that was rightly jettisoned? Pick a cause or industry, and investigate whether any earmarks ever favored it, or research the way earmarks have hurt or helped your state or district and decide for yourself.

Follow-up activity: Find out where your congressional representative stands on the ban on earmarks and write to support or dissuade him or her.

Such budgetary allocations aren’t always looked upon favorably by constituents. Consider, for example, the passage of the ACA in 2010. The desire for comprehensive universal health care had been a driving position of the Democrats since at least the 1960s. During the 2008 campaign, that desire was so great among both Democrats and Republicans that both parties put forth plans. When the Democrats took control of Congress and the presidency in 2009, they quickly began putting together their plan. Soon, however, the politics grew complex, and the proposed plan became very contentious for the Republican Party.

Nevertheless, the desire to make good on a decades-old political promise compelled Democrats to do everything in their power to pass something. They offered sympathetic members of the Republican Party valuable budgetary concessions; they attempted to include allocations they hoped the opposition might feel compelled to support; and they drafted the bill in a purposely complex manner to avoid future challenges. These efforts, however, had the opposite effect. The Republican Party’s constituency interpreted the allocations as bribery and the bill as inherently flawed and felt it should be scrapped entirely. The more Democrats dug in, the more frustrated the Republicans became.

The Republican opposition, which took control of the House during the 2010 midterm elections, promised constituents they would repeal the law. Their attempts were complicated, however, by the fact that Democrats still held the Senate and the presidency. Yet, the desire to represent the interests of their constituents compelled Republicans to use another tool at their disposal, the symbolic vote. During the 112th and 113th Congresses, Republicans voted more than sixty times to either repeal or severely limit the reach of the law. They understood these efforts had little to no chance of ever making it to the president’s desk. And if they did, he would certainly have vetoed them. But it was important for these representatives to demonstrate to their constituents that they understood their wishes and were willing to act on them.

Historically, representatives have been able to balance their role as members of a national legislative body with their role as representatives of a smaller community. The Obamacare fight, however, gave a boost to the growing concern that the power structure in Washington divides representatives from the needs of their constituency. [7] This has exerted pressure on representatives to the extent that some now pursue a more straightforward delegate approach to representation. Indeed, following the 2010 election, a handful of Republicans began living in their offices in Washington, convinced that by not establishing a residence in Washington, they would appear closer to their constituents at home. [8]

COLLECTIVE REPRESENTATION AND CONGRESSIONAL APPROVAL

The concept of collective representation describes the relationship between Congress and the United States as a whole. That is, it considers whether the institution itself represents the American people, not just whether a particular member of Congress represents their district. Predictably, it is far more difficult for Congress to maintain a level of collective representation than it is for individual members of Congress to represent their own constituents. Not only is Congress a mixture of different ideologies, interests, and party affiliations, but the collective constituency of the United States has an even-greater level of diversity. Nor is it a solution to attempt to match the diversity of opinions and interests in the United States with those in Congress. Indeed, such an attempt would likely make it more difficult for Congress to maintain collective representation. Its rules and procedures require Congress to use flexibility, bargaining, and concessions. Yet, it is this flexibility and these concessions, which many now interpret as corruption, that tend to engender the high public disapproval ratings experienced by Congress.

After many years of deadlocks and bickering on Capitol Hill, the national perception of Congress has tended to run under 20 percent approval in recent years, with large majorities disapproving. Through mid-2021, the Congress, narrowly under Democratic control, was receiving higher approval ratings, above 30 percent. However, congressional approval still lags public approval of the presidency and Supreme Court by a considerable margin. In the two decades following the Watergate scandal in the early 1970s, the national approval rating of Congress hovered between 30 and 40 percent, then trended upward in the 1990s, before trending downward in the twenty-first century. [9]

Yet, incumbent reelections have remained largely unaffected. The reason has to do with the remarkable ability of many in the United States to separate their distaste for Congress from their appreciation for their own representative. Paradoxically, this tendency to hate the group but love one’s own representative actually perpetuates the problem of poor congressional approval ratings. The reason is that it blunts voters’ natural desire to replace those in power who are earning such low approval ratings.

As decades of polling indicate, few events push congressional approval ratings above 50 percent. Indeed, when the ratings are graphed, the two noticeable peaks are at 57 percent in 1998 and 84 percent in 2001. In 1998, according to Gallup polling, the rise in approval accompanied a similar rise in other mood measures, including President Bill Clinton’s approval ratings and general satisfaction with the state of the country and the economy. In 2001, approval spiked after the September 11 terrorist attacks and the Bush administration launched the “War on Terror,” sending troops first to Afghanistan and later to Iraq. War has the power to bring majorities of voters to view their Congress and president in an overwhelmingly positive way. [10]

Nevertheless, all things being equal, citizens tend to rate Congress more highly when things get done and more poorly when things do not get done. For example, during the first half of President Obama’s first term, Congress’s approval rating reached a relative high of about 40 percent. Both houses were dominated by members of the president’s own party, and many people were eager for Congress to take action to end the deep recession and begin to repair the economy. Millions were suffering economically, out of work, or losing their jobs, and the idea that Congress was busy passing large stimulus packages, working on finance reform, and grilling unpopular bank CEOs and financial titans appealed to many. Approval began to fade as the Republican Party slowed the wheels of Congress during the tumultuous debates over Obamacare and reached a low of 9 percent following the federal government shutdown in October 2013.

One of the events that began the approval rating’s downward trend was Congress’s divisive debate over national deficits. A deficit is what results when Congress spends more than it has available. It then conducts additional deficit spending by increasing the national debt. Many modern economists contend that during periods of economic decline, the nation should run deficits, because additional government spending has a stimulating effect that can help restart a sluggish economy. Despite this benefit, voters rarely appreciate deficits. They see Congress as spending wastefully during a time when they themselves are cutting costs to get by.

The disconnect between the common public perception of running a deficit and its legitimate policy goals is frequently exploited for political advantage. For example, while running for the presidency in 2008, Barack Obama slammed the deficit spending of the George W. Bush presidency, saying it was “unpatriotic.” This sentiment echoed complaints Democrats had been issuing for years as a weapon against President Bush’s policies. Following the election of President Obama and the Democratic takeover of the Senate, the concern over deficit spending shifted parties, with Republicans championing a spendthrift policy as a way of resisting Democratic policies.

LINK TO LEARNING

Find your representative at the U.S. House website and then explore his or her website and social media accounts to see whether the issues on which your representative spends time are the ones you think are most appropriate.

CHAPTER REVIEW

See the Chapter 11.3 Review for a summary of this section, the key vocabulary , and some review questions to check your knowledge.

- Steven S. Smith. 1999. The American Congress. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ↵

- Edmund Burke, "Speech to the Electors of Bristol," 3 November 1774, http://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch13s7.html (May 1, 2016). ↵

- EMILY's List, "Our History," https://www.emilyslist.org/pages/entry/our-history (June 1, 2021). ↵

- Michele L. Swers, "More Republican women than before will serve this Congress. Here's why." Washington Post , 5 January 2021. ↵

- Jennifer E. Manning, August 5, 2021. "Membership of the 117th Congress: A Profile." Congressional Research Service. ( https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46705 ) ↵

- "Statement by John McCain on Banning Earmarks," 13 March 2008, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=90739 (May 15, 2016); "Press Release - John McCain’s Economic Plan," 15 April 2008, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=94082 (May 15, 2016). ↵

- Kathleen Parker, "Health-Care Reform’s Sickeningly Sweet Deals," The Washington Post, 10 March 2010, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/03/09/AR2010030903068.html (May 1, 2016); Dana Milbank, "Sweeteners for the South," The Washington Post, 22 November 2009, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/11/21/AR2009112102272.html (May 1, 2016); Jeffrey H. Anderson, "Nebraska’s Dark-Horse Candidate and the Cornhusker Kickback," The Weekly Standard, 4 May 2014. ↵

- Phil Hirschkorn and Wyatt Andrews, "One-Fifth of House Freshmen Sleep in Offices," CBS News, 22 January 2011, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/one-fifth-of-house-freshmen-sleep-in-offices/ (May 1, 2016). ↵

- “Congress and the Public,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/congress-public.aspx (May 15, 2016). ↵

- "Congress and the Public," http://www.gallup.com/poll/1600/congress-public.aspx (May 15, 2016). ↵

an elected leader’s looking out for his or her constituents while carrying out the duties of the office

a model of representation in which representatives feel compelled to act on the specific stated wishes of their constituents

a model of representation in which representatives feel at liberty to act in the way they believe is best for their constituents

a model of representation in which members of Congress act as either trustee or delegate, based on rational political calculations about who is best served, the constituency or the nation

the extent to which a body of representatives represents the descriptive characteristics of their constituencies, such as class, race, ethnicity, and gender

federal spending intended to benefit a particular district or set of constituents

the relationship between Congress and the United States as a whole, and whether the institution itself represents the American people

Congressional Representation Copyright © 2022 by Lumen Learning and OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > The American Congress

- > Representation and Lawmaking in Congress

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The Troubled Congress

- 2 Representation and Lawmaking in Congress

- 3 Congressional Elections and Policy Alignments

- 4 Members, Goals, Resources, and Strategies

- 5 Parties and Leaders

- 6 The Standing Committees

- 7 The Rules of the Legislative Game

- 8 The Floor and Voting

- 9 Congress and the President

- 10 Congress and the Courts

- 11 Congress, Lobbyists, and Interest Groups

- 12 Congress and Budget Politics

- Appendix Introduction to the Spatial Theory of Legislating

2 - Representation and Lawmaking in Congress

The Constitutional and Historical Context

In representation and lawmaking, rules matter. The constitution creates both a system of representation and a process for making law through two chambers of Congress and a president. One constitutional rule determines the official constituencies of representatives and senators; another determines how members of Congress are elected and how long they serve. Other constitutional rules outline the elements of the legislative process – generally the House, Senate, and president must agree on legislation before it can become law, unless a two-thirds majority of each chamber can override a presidential veto. More detailed rules about the electoral and legislative processes are left for federal statutes, state laws, and internal rules of the House and Senate.

Although the constitutional rules governing representation and lawmaking have changed in only a few ways since Congress first convened in 1789, other features of congressional politics have changed in many ways. The Constitution says nothing about congressional parties and committees, yet most legislation in the modern Congress is written in committees. Committees are appointed through the parties, and party leaders schedule legislation for consideration on the floor. In this chapter, we describe the basic elements of the representation and lawmaking processes and provide an overview of the development of the key components of the modern legislative process.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Representation and Lawmaking in Congress

- Steven S. Smith , Washington University, St Louis , Jason M. Roberts , University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill , Ryan J. Vander Wielen , Temple University, Philadelphia

- Book: The American Congress

- Online publication: 05 August 2013

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107337749.003

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Directory of Representatives

Also referred to as a congressman or congresswoman, each representative is elected to a two-year term serving the people of a specific congressional district. The number of voting representatives in the House is fixed by law at no more than 435, proportionally representing the population of the 50 states. Currently, there are five delegates representing the District of Columbia, the Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. A resident commissioner represents Puerto Rico. Learn more about representatives at The House Explained .

Key to Room Codes

- CHOB: Cannon House Office Building

- LHOB: Longworth House Office Building

- RHOB: Rayburn House Office Building

- View the campus map

A Note About Room Numbering

- By State and District

- By Last Name

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | R | 1330 LHOB | (202) 225-4931 | Appropriations|Natural Resources | |

| 2nd | R | 1504 LHOB | (202) 225-2901 | Agriculture|Judiciary | |

| 3rd | R | 2469 RHOB | (202) 225-3261 | Armed Services | |

| 4th | R | 266 CHOB | (202) 225-4876 | Appropriations | |

| 5th | R | 1337 LHOB | (202) 225-4801 | Armed Services|Homeland Security|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 6th | R | 170 CHOB | (202) 225-4921 | Oversight and Accountability|Energy and Commerce | |

| 7th | D | 1035 LHOB | (202) 225-2665 | Armed Services|House Administration|Joint Committee of Congress on the Library|Ways and Means |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Large | D | 153 CHOB | (202) 225-5765 | Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delegate | R | 2001 RHOB | (202) 225-8577 | Foreign Affairs|Natural Resources|Veterans' Affairs |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | R | 460 CHOB | (202) 225-2190 | Ways and Means | |

| 2nd | R | 1229 LHOB | (202) 225-3361 | Homeland Security|Small Business|Veterans' Affairs | |

| 3rd | D | 1114 LHOB | (202) 225-4065 | Armed Services|Natural Resources | |

| 4th | D | 207 CHOB | (202) 225-9888 | Foreign Affairs|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 5th | R | 252 CHOB | (202) 225-2635 | Oversight and Accountability|Judiciary | |

| 6th | R | 1429 LHOB | (202) 225-2542 | Appropriations|Veterans' Affairs | |

| 7th | D | 1203 LHOB | (202) 225-2435 | Education and the Workforce|Natural Resources | |

| 8th | R | 1214 LHOB | (202) 225-4576 | Energy and Commerce|Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic | |

| 9th | R | 2057 RHOB | (202) 225-2315 | Oversight and Accountability|Natural Resources |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | R | 2422 RHOB | (202) 225-4076 | Agriculture|Intelligence|Transportation and Infrastructure|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 2nd | R | 1533 LHOB | (202) 225-2506 | Financial Services|Foreign Affairs|Intelligence | |

| 3rd | R | 2412 RHOB | (202) 225-4301 | Appropriations | |

| 4th | R | 202 CHOB | (202) 225-3772 | Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | R | 408 CHOB | (202) 225-3076 | Agriculture|Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 2nd | D | 2445 RHOB | (202) 225-5161 | Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 3rd | R | 1032 LHOB | (202) 225-2523 | Education and the Workforce|Judiciary|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 4th | D | 268 CHOB | (202) 225-3311 | Ways and Means | |

| 5th | R | 2256 RHOB | (202) 225-2511 | Budget|Natural Resources|Judiciary | |

| 6th | D | 172 CHOB | (202) 225-5716 | Foreign Affairs|Intelligence|Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic | |

| 7th | D | 2311 RHOB | (202) 225-7163 | Energy and Commerce | |

| 8th | D | 2004 RHOB | (202) 225-1880 | Armed Services|Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Fed Govt|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 9th | D | 209 CHOB | (202) 225-4540 | Appropriations | |

| 10th | D | 503 CHOB | (202) 225-2095 | Education and the Workforce|Transportation and Infrastructure|Ethics | |

| 11th | D | 1236 LHOB | (202) 225-4965 | ||

| 12th | D | 2470 RHOB | (202) 225-2661 | Appropriations|Budget | |

| 13th | R | 1535 LHOB | (202) 225-1947 | Agriculture|Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 14th | D | 174 CHOB | (202) 225-5065 | Homeland Security|Judiciary | |

| 15th | D | 1404 LHOB | (202) 225-3531 | Natural Resources|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 16th | D | 272 CHOB | (202) 225-8104 | Energy and Commerce | |

| 17th | D | 306 CHOB | (202) 225-2631 | Armed Services|Oversight and Accountability|Select Comm on the Strategic Competition US and China | |

| 18th | D | 1401 LHOB | (202) 225-3072 | Judiciary|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 19th | D | 304 CHOB | (202) 225-2861 | Armed Services|Budget|Ways and Means | |

| 20th | R | 2468 RHOB | (202) 225-2915 | Transportation and Infrastructure|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 21st | D | 2081 RHOB | (202) 225-3341 | Agriculture|Foreign Affairs | |

| 22nd | R | 2465 RHOB | (202) 225-4695 | Appropriations|Budget|Joint Committee of Congress on the Library | |

| 23rd | R | 1029 LHOB | (202) 225-5861 | Energy and Commerce|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 24th | D | 2331 RHOB | (202) 225-3601 | Agriculture|Armed Services|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 25th | D | 2342 RHOB | (202) 225-5330 | Energy and Commerce|Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic | |

| 26th | D | 2262 RHOB | (202) 225-5811 | Transportation and Infrastructure|Veterans' Affairs | |

| 27th | R | 144 CHOB | (202) 225-1956 | Appropriations|Intelligence|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 28th | D | 2423 RHOB | (202) 225-5464 | Small Business|Ways and Means | |

| 29th | D | 2181 RHOB | (202) 225-6131 | Energy and Commerce | |

| 30th | D | 2309 RHOB | (202) 225-4176 | Judiciary | |

| 31st | D | 1610 LHOB | (202) 225-5256 | Natural Resources|Transportation and Infrastructure | |

| 32nd | D | 2365 RHOB | (202) 225-5911 | Financial Services|Foreign Affairs | |

| 33rd | D | 108 CHOB | (202) 225-3201 | Appropriations | |

| 34th | D | 506 CHOB | (202) 225-6235 | Intelligence|Ways and Means | |

| 35th | D | 2227 RHOB | (202) 225-6161 | Appropriations|House Administration | |

| 36th | D | 2454 RHOB | (202) 225-3976 | Foreign Affairs|Judiciary | |

| 37th | D | 1419 LHOB | (202) 225-7084 | Foreign Affairs|Natural Resources | |

| 38th | D | 2428 RHOB | (202) 225-6676 | Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Fed Govt|Ways and Means | |

| 39th | D | 2078 RHOB | (202) 225-2305 | Education and the Workforce|Veterans' Affairs | |

| 40th | R | 1306 LHOB | (202) 225-4111 | Financial Services|Foreign Affairs | |

| 41st | R | 2205 RHOB | (202) 225-1986 | Appropriations | |

| 42nd | D | 1305 LHOB | (202) 225-7924 | Oversight and Accountability|Homeland Security|Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic | |

| 43rd | D | 2221 RHOB | (202) 225-2201 | Financial Services | |

| 44th | D | 2312 RHOB | (202) 225-8220 | Energy and Commerce | |

| 45th | R | 1127 LHOB | (202) 225-2415 | Education and the Workforce|Ways and Means|Select Comm on the Strategic Competition US and China | |

| 46th | D | 2301 RHOB | (202) 225-2965 | Homeland Security|Judiciary | |

| 47th | D | 1233 LHOB | (202) 225-5611 | Oversight and Accountability|Natural Resources | |

| 48th | R | 2108 RHOB | (202) 225-5672 | Foreign Affairs|Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Fed Govt|Judiciary|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 49th | D | 2352 RHOB | (202) 225-3906 | Natural Resources|Veterans' Affairs | |

| 50th | D | 1201 LHOB | (202) 225-0508 | Budget|Energy and Commerce | |

| 51st | D | 1314 LHOB | (202) 225-2040 | Armed Services|Foreign Affairs | |

| 52nd | D | 2334 RHOB | (202) 225-8045 | Financial Services |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | D | 2111 RHOB | (202) 225-4431 | Energy and Commerce | |

| 2nd | D | 2400 RHOB | (202) 225-2161 | Natural Resources|Judiciary|Rules | |

| 3rd | R | 1713 LHOB | (202) 225-4761 | Oversight and Accountability|Natural Resources | |

| 4th | R | 2455 RHOB | (202) 225-4676 | Budget|Science, Space, and Technology | |

| 5th | R | 2371 RHOB | (202) 225-4422 | Armed Services|Natural Resources | |

| 6th | D | 1323 LHOB | (202) 225-7882 | Foreign Affairs|Intelligence | |

| 7th | D | 1230 LHOB | (202) 225-2645 | Financial Services | |

| 8th | D | 1024 LHOB | (202) 225-5625 | Agriculture|Science, Space, and Technology |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | D | 1501 LHOB | (202) 225-2265 | Ways and Means | |

| 2nd | D | 2449 RHOB | (202) 225-2076 | Armed Services|Education and the Workforce | |

| 3rd | D | 2413 RHOB | (202) 225-3661 | Appropriations | |

| 4th | D | 2137 RHOB | (202) 225-5541 | Financial Services|Intelligence | |

| 5th | D | 2458 RHOB | (202) 225-4476 | Agriculture|Education and the Workforce |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At Large | D | 1724 LHOB | (202) 225-4165 | Energy and Commerce |

| District | Name | Party | Office Room | Phone | Committee Assignment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|