Essay Papers Writing Online

A comprehensive guide to writing a response essay that will help you ace your academic assignments.

Writing a response essay can be a challenging task, as it requires you to analyze a piece of literature, a movie, an article, or any other work and provide your personal reaction to it. This type of essay allows you to express your thoughts and feelings about the content you’re responding to, and it can help you develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

In order to craft a compelling response essay, you need to carefully read and understand the work you’re responding to, identify key themes and arguments, and formulate a clear and coherent response. This guide will provide you with tips and strategies to help you write an effective response essay that engages your readers and communicates your ideas effectively.

Key Elements of a Response Essay

A response essay typically includes the following key elements:

- Introduction: Begin with a brief summary of the text you are responding to and your main thesis statement.

- Summary: Provide a concise summary of the text, focusing on the key points and arguments.

- Analysis: Analyze and evaluate the text, discussing its strengths, weaknesses, and the effectiveness of its arguments.

- Evidence: Support your analysis with evidence from the text, including quotes and examples.

- Personal Reaction: Share your personal reaction to the text, including your thoughts, feelings, and opinions.

- Conclusion: Sum up your response and reiterate your thesis statement, emphasizing the significance of your analysis.

By incorporating these key elements into your response essay, you can effectively engage with the text and provide a thoughtful and well-supported response.

Understanding the Assignment

Before you start writing your response essay, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the assignment requirements. Read the prompt carefully and identify the main objectives of the assignment. Make sure you understand what the instructor expects from your response, whether it is a critical analysis of a text, a personal reflection, or a synthesis of different sources.

Pay attention to key elements such as:

- The topic or subject matter

- The purpose of the response

- The audience you are addressing

- The specific guidelines or formatting requirements

Clarifying any doubts about the assignment will help you focus your response and ensure that you meet all the necessary criteria for a successful essay.

Analyzing the Prompt

Before you start writing your response essay, it is crucial to thoroughly analyze the prompt provided. Understanding the prompt is essential for crafting a coherent and well-structured response that addresses the key points effectively. Here are some key steps to consider when analyzing the prompt:

- Carefully read the prompt multiple times to fully grasp the main question or topic that needs to be addressed.

- Identify the key words and phrases in the prompt that will guide your response and help you stay focused on the main theme.

- Consider any specific instructions or requirements outlined in the prompt, such as the length of the essay, the format to be used, or the sources to be referenced.

- Break down the prompt into smaller parts or components to ensure that you cover all aspects of the question in your response.

- Clarify any terms or concepts in the prompt that are unclear to you, and make sure you have a solid understanding of what is being asked of you.

By analyzing the prompt carefully and methodically, you can ensure that your response essay is well-structured, focused, and directly addresses the main question or topic at hand.

Developing a Thesis Statement

One of the most critical aspects of writing a response essay is developing a clear and strong thesis statement. A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of your essay. It sets the tone for your entire response and helps guide your reader through your arguments.

When developing your thesis statement, consider the following tips:

| 1. | Identify the main topic or issue you will be responding to. |

| 2. | State your position or stance on the topic clearly and concisely. |

| 3. | Provide a brief preview of the key points or arguments you will present in your essay to support your thesis. |

Remember, your thesis statement should be specific, focused, and debatable. It should also be located at the end of your introduction paragraph to ensure it captures the reader’s attention and sets the stage for the rest of your essay.

Structuring Your Response

When structuring your response essay, it’s essential to follow a clear and logical format. Start with an introduction that provides background information on the topic and presents your thesis statement. Then, organize your body paragraphs around key points or arguments that support your thesis. Make sure each paragraph focuses on a single idea and provides evidence to back it up.

After presenting your arguments, include a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your thesis. Remember to use transitions between paragraphs to ensure a smooth flow of ideas. Additionally, consider the overall coherence and cohesion of your response to make it engaging and easy to follow for the reader.

Main Body Paragraphs

When writing the main body paragraphs of your response essay, it’s essential to present your arguments clearly and logically. Each paragraph should focus on a separate point or idea related to the topic. Start each paragraph with a topic sentence that introduces the main idea, and then provide supporting evidence or examples to reinforce your argument.

- Make sure to organize your paragraphs in a coherent and sequential manner, so that your essay flows smoothly and is easy for the reader to follow.

- Use transition words and phrases, such as “furthermore,” “in addition,” or “on the other hand,” to connect your ideas and create a cohesive structure.

- Cite sources and provide proper references to strengthen your arguments and demonstrate the credibility of your analysis.

Remember to analyze and evaluate the information you present in each paragraph, rather than simply summarizing it. Engage critically with the texts, articles, or sources you are referencing, and develop your own perspective or interpretation based on the evidence provided.

Related Post

How to master the art of writing expository essays and captivate your audience, convenient and reliable source to purchase college essays online, step-by-step guide to crafting a powerful literary analysis essay, unlock success with a comprehensive business research paper example guide, unlock your writing potential with writers college – transform your passion into profession, “unlocking the secrets of academic success – navigating the world of research papers in college”, master the art of sociological expression – elevate your writing skills in sociology.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Summary/Response Essays: Overview

A summary/response essay may, at first, seem like a simplistic exercise for a college course. But the truth is that most academic writing requires us to successfully accomplish at least two tasks: summarizing what others have said and presenting what you have to say. Because of this, summarizing and responding are core skills that every writer should possess.

Being able to write an effective summary helps us make sense of what others have to say about a topic and how they choose to say it. As writers, we all need to make an effort to recognize, understand, and consider various perspectives about different issues. One way to do this is to accurately summarize what someone else has written, but accomplishing this requires us to first be active and engaged readers.

Along with the other methods covered in the Reading Critically chapter , writing a good summary requires taking good notes about the text. Your notes should include factual information from the text, but your notes might also capture your reactions to the text—these reactions can help you build a thoughtful and in-depth response.

Responding to a text is a crucial part of entering into an academic conversation. An effective summary proves you understand the text; your response allows you to draw on your own experiences and prior knowledge so that you can talk back to the text.

As you read, make notes, and summarize a text, you’ll undoubtedly have immediate reactions. Perhaps you agree with almost everything or find yourself frustrated by what the author writes. Taking those reactions and putting them into a piece of academic writing can be challenging because our personal reactions are based on our history, culture, opinions, and prior knowledge of the topic. However, an academic audience will expect you to have good reasons for the ways you have responded to a text, so it’s your responsibility to critically reflect on how you have reacted and why.

The ability to recognize and distinguish between types of ideas is key to successful critical reading.

Types of Ideas You Will Encounter When Reading a Text

- Fact: an observable, verifiable idea or phenomenon

- Opinion: a judgment based on fact

- Belief: a conviction or judgment based on culture or values

- Prejudice: an opinion (judgment) based on logical fallacies or on incorrect, insufficient information

After you have encountered these types of ideas when reading a text, your next job will be to consider how to respond to what you’ve read.

Four Ways to Respond to a Text

- Reflection. Did the author teach you something new? Perhaps they made you look at something familiar in a different way.

- Agreement. Did the author write a convincing argument? Were their claims solid, and supported by credible evidence?

- Disagreement. Do you have personal experiences, opinions, or knowledge that lead you to different conclusions than the author? Do your opinions about the same facts differ?

- Note Omissions. If you have experience with or prior knowledge on the topic, you may be able to identify important points that the author failed to include or fully address.

You might also analyze how the author has organized the text and what the author’s purposes might be, topics covered in the Reading Critically chapter .

Key Features

A brief summary of the text.

Include Publication Information. An effective summary includes the author’s name, the text’s title, the place of publication, and the date of publication—usually in the opening lines.

Identify Main Idea and Supporting Ideas. The main idea includes both the topic of the text and the author’s argument, claim, or perspective. Supporting ideas help the author demonstrate why their argument or claim is true. Supporting ideas may also help the audience understand the topic better, or they may be used to persuade the audience to agree with the author’s viewpoints.

Make Connections Between Ideas. Remember that a summary is not a bullet-point list of the ideas in a text. In order to give your audience a complete idea of what the author intended to say, you need to explain how ideas in the text are related to one another. Consider using transition phrases.

Be Objective and Accurate. Along with being concise, a summary should be a description of a text, not an evaluation. While you may have strong feelings about what the author wrote, your goal in a summary is to objectively capture what was written. Additionally, a summary needs to accurately represent the ideas, opinions, facts, and judgments presented in a text. Don’t misrepresent or manipulate the author’s words.

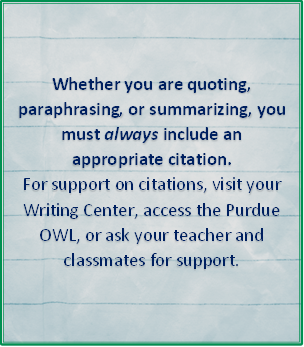

Do Not Include Quotes. Summaries are short. The purpose of a summary is for you to describe a text in your own words . For this reason, you should focus on paraphrasing rather than including direct quotes from the text in your summary.

Thoughtful and Respectful Response to the Text

Consider Your Reactions. Your response will be built on your reactions to the text, so you need to carefully consider what reactions you had and how you can capture those reactions in writing.

Organize Your Reactions. Dumping all of your reactions onto the page might be useful to just get your ideas out, but it won’t be useful for a reader. You need to organize your reactions. For example, you might develop sections that focus on where you agree with the author, where you disagree, how the author uses rhetoric, and so on.

Create a Conversation. Avoid the trap of writing a response that is too much about your ideas and not enough about the author’s ideas. Your response should remain engaged with the author’s ideas. Keep the conversation alive by making sure you regularly reference the author’s key points as you talk back to the text.

Be Respectful. We live in an age when it’s very easy to anonymously air our grievances online, and we’ve seen how Reddit boards, YouTube comments, and Twitter threads can quickly devolve into disrespectful, toxic spaces. In a summary/response essay, as in other academic writing, you are not required to agree with everything an author writes—but you should state your objections and reactions respectfully. Imagine the author is standing in front of you, and write your response as if you value and respect their ideas as much as you would like them to value and respect yours.

Distinguish Between an Author’s Ideas and Your Own

Signal Phrases. A summary/response essay, especially your response, will include a mix of an author’s ideas and your ideas. It’s important that you clearly distinguish which ideas in your essay are yours, which are the author’s, and even others’ ideas that the author might be citing. Signal phrases are how you accomplish this. Remember to use the author’s last name and an accurate verb.

Examples of Signal Phrases

Poor Signal Phrases: “They say…” “The article states…” “The author says…”

Effective Signal Phrases: “Smith argues…” “Baez believes…” “Henning references Chan Wong’s research about…”

Drafting Checklists

These questions should help guide you through the stages of drafting your summary/response essay.

- Have you identified all the necessary publication information for the text that you will need for your summary?

- Have you identified the text’s main ideas and supporting ideas?

- What were your initial reactions to the text?

- What new perspectives do you have on the topic covered in the text?

- Do you ultimately agree or disagree with the author’s points? A little of both?

- Has the author omitted any points or ideas they should have covered?

- Has the author organized their text effectively for their purpose?

- Have they used rhetoric effectively for their audience?

- Have your reactions to the text changed since you first read it? Why or why not?

Writing and Revising

- Does your summary clearly tell your reader the author’s name, the text’s title, the place of publication, and the publication data?

- Has your summary effectively informed your reader about the text’s main ideas and supporting ideas? Have you made the connections between those ideas clear for your reader by using effective transition phrases?

- Would your reader think your summary is objective and accurate?

- You haven’t included any quotes in your summary, right?

- Does your response present your reactions to the text in an organized way that will make sense to your reader?

- Does your response create a conversation between you and the author by regularly referencing ideas from the text?

- Would your reader think that your response is respectful of the author’s ideas, opinions, and beliefs?

- Have you used signal phrases to help your reader recognize which ideas are the author’s and which ideas are yours?

- Have you carefully proofread your essay to correct any grammar, mechanics, punctuation, and spelling errors?

- Have you formatted your document appropriately and used citations when necessary?

Sources Used to Create this Chapter

Parts of this chapter were remixed from:

- First-Year Composition by Leslie Davis and Kiley Miller, which was published under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Starting the Journey: An Intro to College Writing Copyright © by Leonard Owens III; Tim Bishop; and Scott Ortolano is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Summary, Analysis, Response: A Functional Approach to Reading, Understanding, and Responding to Nonfiction

This resource gives students a way to approach reading and responding to nonfiction without requiring them to write an essay. It is relatively formulaic but builds skills through scaffolding concepts and encouraging students to develop the confidence necessary to start reading critically and making arguments about the nonfiction they read.

Find below a PDF of the SAR GUIDELINES :

Find below a PDF of two types of PEER REVIEW forms for the SAR:

Find below a PDF of two types of ASSESSMENT forms for the SAR:

********************************************************************************************

CLICK HERE for a link to guidelines for writing a Summary, Analysis, Response as well as a sample SAR, tips and warnings. Hard copy is below, but the formatting is kind of messed up.

SAR (Summary, Analysis, Response) Guidelines, 2015 / Ramsey

--SARs should be exactly three paragraphs long and no longer than two typed, double-spaced pages.

--Include a title: SAR #1: “Title of Essay” (or SAR #2: “Title of Essay,” etc.)

--SARs should be free of errors in conventions, written in present tense in an academic tone (often more formal than the tone of the essay you’re writing about), and MLA formatted.

Paragraph 1 (of 3): SUMMARIZE. See page 4.

Summarize the ideas, mainly with your own words, including BRIEF (2-5 word) cited direct quotations when necessary. Include the author’s first and last names—correctly spelled—as well as the essay title in quotation marks. This should be the shortest of the three paragraphs.

Paragraph 2 (of 3): ANALYZE. See pages 5 – 7.

Identify parts of the reading, including . . .

a. The context in which the essay was written (a contribution to discussion or debate about what?)

b. The audience for whom the essay was intended.

c. The purpose of the essay. (Remember, most essays have at least some element of persuasion.)

d. The organizational form(s) of the essay. Don’t describe it—identify which TYPE it is.

e. The tone(s) of the essay. Include a “blend” quotation proving the strongest of the essay’s tones.

See pages 8 - 9 for information about blending quotations.

f. The tools used to accomplish the essay’s purpose. Identify at least THREE tools, and include a

“blend” quotation that illustrates at least one of these tools.

g. The thesis of essay. The thesis could be explicitly stated in the essay or more obliquely implied.

Include discussion of all seven things above (a-g, plus direct quotations for tone and tools), in the order outlined above .

Paragraph 3 (of 3): RESPOND / REACT.

Give a personal response to the reading. What ideas do you find interesting? Why? (Even if you don’t like the essay, you should still be able to find something interesting about it.) Do you agree with the author’s “message”? You can also evaluate and/or challenge the essay in this paragraph. Is the author’s purpose achieved? How well does the author prove her/his argument? What could someone on the other side of this argument say, and how valid would that criticism be? What flaws in logic do you see in the author’s argument?

This is the only paragraph where you should use the first-person “I.”

************************************************************************************

HERE’S A SAMPLE SAR

A Student

Ramsey

Writing 122

23 September 2015

SAR #1: “The Culture of American Film”

In “The Culture of American Film,” Julia Newman argues that analyzing movies for “cultural significance” (294) can lead to greater understanding of changes in our society.

This essay was written in the context of a growing movement in academia toward viewing popular films as literature and analyzing movies as cultural text. Newman’s intended audience is probably university-level scholars, but her ideas are accessible to anyone interested in examining film as it suggests underlying societal structures. One purpose of this essay is to explain how to view films as indications of what’s going on in our society, but Newman also wants to persuade the reader that there’s more to movies than just entertainment. The organizational form of the essay is classification, as Newman places movies into categories of those that do reflect changes in our society and those that do not, then she compares and contrasts these categories. In addition, the essay employs a chronological organizational form in which Newman describes the plots of various movies from 50 years ago to the present. The tone of the essay is consistently encouraging and knowledgeable. There’s a sort of majestic tone to the introduction, too, as Newman pronounces that the “significance of storytelling has diminished over the decades, and cinema has risen to take its place” (291). Tools Newman uses to accomplish her purpose include specific examples of film analyses, an impressive balance between academic and accessible word choices, and concessions to the opposition, like when she writes, “However, it is easy to overstate these connections” (292). The thesis of the essay appears on page 298: “But as cinematic forms of storytelling overtake written forms of expression, the study of movies as complex text bearing cultural messages and values is becoming more and more important.” In other words, we can learn a lot about structural shifts within our culture through studying popular film as literary text.

I found the ideas in this essay quite compelling. The essay makes me want to examine the movies of ten or twenty years ago to consider what they suggested about our society then. The essay also makes me think about films that have been nominated for Academy Awards this year, like The Artist, and what the popularity of this silent movie says about changes taking place in our culture right now. I do wish Newman had used more current examples; most of her examples are so old that I’ve never seen them. I also wonder how much knowledge of history is necessary to really apply her thesis. . . . I don’t think I’ll ever have a strong enough understanding of American history to apply Newman’s ideas to movies that have been popular in the past, and I can’t imagine trying to examine currently popular movies for what they suggest about cultural shifts that are happening right now. It seems like the type of analysis she encourages is only possible in retrospect and with a strong understanding of movements in American history.

Paragraph 1 (of 3): SUMMARIZE.

Summarize the ideas, mainly with your own words, including BRIEF (2-5 word) direct quotations when necessary. Include the author’s first and last names—correctly spelled—as well as the essay title in quotation marks. This should be the shortest of the paragraphs. Keep your summary in the present tense.

Note: The verbs you use in summarizing an essay suggest an author’s purpose and can imply a judgment of that purpose.

If you say, “The author . . .

Tells” (suggests the author’s purpose is to explain or narrate)

Explains” (suggests author’s purpose is to explain or inform)Argues” (suggests author is trying to persuade)

Claims” (suggests author is trying to persuade; further suggests you don’t buy what the author is saying)

Informs” (suggests dryly expository writing)

Persuades” (suggests persuasive writing, duh)

Exposes” (suggests author’s purpose is to investigate something hidden)

Teaches” (suggests author is explaining or informing)

Narrates” (suggests author is telling a personal story)

Relates” (suggests author’s purpose is to explain through comparison)

Distinguishes” (suggests author’s purpose is to explain by contrasting topics)

Compares” (suggests author’s purpose is to draw similarities between topics)

Contrasts” (suggests author’s purpose is to find differences between topics)

Warns” (suggests author’s purpose is to persuade through caution)

Suggests” (suggests gently persuasive writing)

Implies” (suggests persuasive writing; further suggests you’re skeptical about the author’s motivations and/or implications)

Note: Summaries are NOT like movie trailers, designed to entice the viewer into thinking there’s something interesting coming. Instead, summaries should explain clearly and succinctly (briefly) what those interesting ideas ARE and what the author’s argument is.

Sample summaries

In “The Culture of American Film,” Julia Newman claims that analyzing movies for “cultural significance” (294) can lead to greater understanding of our society and of changes in our society.

In “Nothing But Net,” Mark McFadden uses specific examples, questions directed at the reader, and personal experience to argue that instead of protecting “work rules and the rules of common decency” (paragraph 1), internet spying technology is ultimately ineffectual and creates an atmosphere of mistrust.

Paragraph 2 (of 3): Analyze. Keep analysis in the present tense.

Context : This essay is a contribution to a larger discussion or debate about

what? What events or ideas prompted the author to write this essay?

Audience : Who is likely to read this essay? Where was it originally published,

and what type of publication is/was it? Who can access this language?

Purpose *: To entertain? To persuade? To congratulate?

To instruct? To warn? To scold?

To inform or explain? Some combination of these?

Organizational form : Chronological? (in order of time)

Cause and effect? (something causes something)

Comparison and contrast? (similarities and differences)

Classification? (putting things into categories)

Some combination of these?

Tone **: Resigned? Antagonistic? Humorous?

Assured? Happy? Confident?

Sympathetic? Urgent? Encouraging?

Frustrated? Energetic? Pleading?

Detached? Ambivalent? Apathetic?

Clinical? Amused? Smug? Some combination?

Tools : Facts and figures? Illustrations?

Direct quotations? Brevity? (shortness)

Imagery? Analogies?

Expert testimony? Humor or sarcasm?

Personal experience? Similes?

Questions directed at reader? Fallacies? (flaws in logic—don’t

Subheadings? identify fallacies as tools unless you

Concessions to the opposition? plan to criticize the essay in your

Allusions to other works? personal-reaction paragraph)

Thesis: The one or two sentences that best summarize THE POINT of the

essay. (Sometimes the point is implied instead of overtly stated.)

Note: Professional writing does NOT usually look like the traditional five-paragraph form.

*All essays have an element of persuasion.

**Tone usually changes as the essay proceeds.

**********************************************************************************

Name ___________________________________________

OPTIONAL Essay Analysis Worksheet / Ramsey

Use your SAR guidelines to help you fill out the blanks below.

I. Summarize the essay with one to three sentences. The summary should include the author’s full name (correctly spelled), the title of essay (correctly punctuated), and all main ideas. The summary should be written in the present tense and with an academic tone. Include the POINT—this is not like a book jacket.

Example: In “The Culture of American Film,” Julia Newman claims that analyzing movies for “cultural significance” (294) can lead to greater understanding of our society and of changes in our society.

II. Analyze the essay by filling in the blanks below.

Context: This essay is a contribution to a larger discussion or debate about . . .

______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

B. Audience: People most likely to read the essay and agree with the author are _________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________

C. Purpose: The author wrote this essay in order to . . . (circle one or more)

entertain explain/inform persuade* warn congratulate

instruct scold other ________________________________________________

*Every essay has an element of persuasion. I hope you circled “persuade” above.

D. The organizational form of the essay is . . . (check one or more)

_____ chronological (from __________________________ to ________________________)

_____ compare and contrast: author examines similarities and differences between

__________________________________ and _______________________________

_____ classification: author puts types of __________________________________________

into these categories: _____________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

_____ cause and effect: author claims _____________________________________________

_______________________________________________________ cause/contribute to

______________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________

_____ some other form best described as _________________________________________

E. The author’s tone (attitude toward the subject of the essay) at the beginning of the essay

can best be described as ____________________________ and ________________________,

then in page/paragraph number _______, it changes to ________________________________

and __________________________. The concluding tone is __________________________.

F. Tools the author uses to accomplish his/her purpose(s) include ___________________________,

_______________________________, and ________________________________________ .

G. The author’s thesis appears in paragraph/page number___ and is (copy or put in your own words):

_______________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________

(If you copied the thesis, did you put the borrowed words in quotation marks?)

Principles of Proper Quotation Format (MLA format)

Keep quotations as short as possible.

If a sentence begins with quotation marks and ends with quotation marks and contains only words taken from a source, you have not introduced the quotation well. Never have such a "stand-alone" quotation.

A sentence containing a quotation should end with the source and page number (or paragraph number) in parentheses. Usually this parenthetical citation comes before the final period but outside any quotation marks at the end of the sentence.

***************************************************************************************

There are three styles of quotations distinguished by how the passage is incorporated into your own wording:

A. In a "Tag Quotation," an introductory phrase (usually identifying the source of the quotation) is joined by a comma to a full, sentence-long quotation.

Example: According to Grafton, "This need for forbiddenness also accounts for Charity’s voyeuristic impulse to continue watching Harney" (357).

Example: Smith argues, “This insistence seems strange, even forced” (113).

B. In an "Analytic Quotation," a complete sentence of analysis by the student is followed by a colon introducing a quotation that illustrates support for the argument. (The quotation illustrates the student’s analysis.)

Example: Life in North Dormer is intolerably oppressive to Charity: "She is stifled by its petty bourgeois conventions and longs for adventure" (Singley 113).

Example: Tom finds himself wondering why he came: “He couldn’t identify a reason for his own behavior, and this troubled him” (Brown 385).

C. In a "Blend Quotation," a short phrase or even just a single key word is quoted and included in the student’s own sentence in such a fluid way that only the quotation marks may reveal the material to be a quotation. THIS IS THE BEST TYPE OF QUOTATION.

Example: Their “silent lies” (Watson 22) prevent the relationship from ever fully recovering.

Example: From the outset of Edith Wharton's Summer, Charity Royall dramatizes the "American quest for freedom" (Singley 155).

Again, if a sentence begins with quotation marks and ends with quotation marks and contains only words taken from a source, you have not introduced the quotation properly. Never have such a "stand-alone" quotation.

USING DIRECT QUOTATIONS: Work direct quotations directly into the fabric of your sentences.

Tools Smith uses include professional vocabulary, expert testimony, and personal experience. “Studies by the Kaufmann Group indicate a 78% increase in depression” (6).

AGAIN, THIS IS POOR USE OF A DIRECT QUOTATION, and it’s completely unclear. Does it support your identification of professional vocabulary? Expert testimony? Personal experience? Who knows?!

Instead, write something like this “analytic” quotation:

Smith uses personal experience as a tool. He also uses expert testimony: “Studies by the Kaufmann Group indicate a 78% increase in depression” (6).

Or, even better, this “blend” quotation:

Smith uses professional vocabulary and personal experience as tools to convince his readers and engage them. Other tools include expert testimony, as seen in his reference to the study by the Kaufmann Group, which found a “78% increase in depression” associated with second-hand smoke (6).

Advice and warnings about your first SARs . . .

This type of writing is very formulaic, so don’t worry about being pretty or having an engaging “voice.” Instead, be clear.

Write with an academic tone, so avoid “things,” “stuff,” “you,” “kids,” and “nowadays.” Sometimes your tone will be more formal than the author of the essay.

Your summary should include the author’s first and last name—correctly spelled—and the title of the essay. Use first and last names the first time you use refer to the author (in the summary); use only the last name every other time. Don’t refer to the author by her/his first name only.

Students often forget that an essay can have more than one purpose and all essays have at least some element of persuasion.

Analysis paragraphs are often incomplete. It should have ELEVEN things: identification of context, audience, purpose, organizational form, tone, 3 tools, thesis, and two direct quotations.

Be sure to identify which TYPE of organizational form the author uses: compare and contrast? classification (putting things in categories)? chronological? cause and effect?

Don’t be afraid to use “red flag” words to guide your reader through the analysis paragraph. You can actually use the words “purpose,” “tone,” “thesis,” etc. to direct your reader through your SAR.

Limit your opinion to the third paragraph. Much of the second paragraph really is opinion, but state it as fact. This makes you sound like you know what you’re talking about, which is more convincing and more professional.

Remember, longer is not necessarily better, but SOME discussion is good. A one-page SAR is too short. One and a half full pages can be okay, but two full pages is probably best.)

Proofread, use the writing labs, and proofread again before printing.

Re-read the directions, advice, and warnings before printing. There’s a lot to remember here!

No Alignments yet.

Cite this work

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter Five: Summary and Response

As you sharpen your analytical skills, you might realize that you should use evidence from the text to back up the points you make. You might use direct quotes as support, but you can also consider using summary.

A summary is a condensed version of a text, put into your own words. Summarizing is a useful part of the analytical process because it requires you to read the text, interpret and process it, and reproduce the important points using your own language. By doing so, you are (consciously or unconsciously) making choices about what matters, what words and phrases mean, and how to articulate their meaning.

Often (but not always), response refers to a description of a reader’s experience and reactions as they encounter a text. Response papers track how you feel and what you think as you move through a text. More importantly, responses also challenge you to evaluate exactly how a text acts upon you—to make you feel or think a certain way—using language or images. While a response is not an analysis, it will help you generate ideas for the analytical process.

Chapter Vocabulary

|

| Definition |

|

| the verbatim use of another author’s words. Can be used as evidence to support your claim, or as language to analyze/close-read to demonstrate an interpretation or insight. |

|

| author reiterates a main idea, argument, or detail of a text in their own words without drastically altering the length of the passage(s) they paraphrase. Contrast with summary. |

|

| a mode of writing that values the reader’s experience of and reactions to a text. |

|

| a rhetorical mode in which an author reiterates the main ideas, arguments, and details of a text in their own words, condensing a longer text into a smaller version. Contrast with paraphrase. |

Identifying Main Points, Concerns, and Images

If you ever watch TV shows with a serial plot, you might be familiar with the phrase “Previously, on _________.” The snippets at the beginning of an episode are designed to remind the viewer of the important parts of previous episodes—but how do makers of the show determine what a viewer needs to be refreshed on? And why am I watching full episodes if they’ll just tell me what I need to know in the first minute of the next episode?

Typically, the makers of the show choose short, punchy bits that will be relevant in the new episode’s narrative arc. For instance, a “Previously, on The Walking Dead ” might have a clip from ten episodes ago showing zombies invading Hershel’s farm if the new episode focuses on Hershel and his family. Therefore, these “previously ons” hook the viewer by showcasing only exciting parts and prime the viewer for a new story by planting specific details in their mind. Summaries like this are driven by purpose, and consequently have a specific job to do in choosing main points.

You, too, should consider your rhetorical purpose when you begin writing summary. Whether you are writing a summary essay or using summary as a tool for analysis, your choices about what to summarize and how to summarize it should be determined by what you’re trying to accomplish with your writing.

As you engage with a text you plan to summarize, you should begin by identifying main points, recurring images, or concerns and preoccupations of the text. (You may find the Engaged Reading Strategies appendix of this book useful.) After reading and rereading, what ideas stick with you? What does the author seem distracted by? What keeps cropping up?

Tracking Your Reactions

As you read and reread a text, you should take regular breaks to check in with yourself to track your reactions. Are you feeling sympathetic toward the speaker, narrator, or author? To the other characters? What other events, ideas, or contexts are you reminded of as you read? Do you understand and agree with the speaker, narrator, or author? What is your emotional state? At what points do you feel confused or uncertain, and why?

Try out the double-column note-taking method. As illustrated below, divide a piece of paper into two columns; on the left, make a heading for “Notes and Quotes,” and on the right, “Questions and Reactions.” As you move through a text, jot down important ideas and words from the text on the left, and record your intellectual and emotional reactions on the right. Be sure to ask prodding questions of the text along the way, too.

| Notes and Quotes | Questions and Reactions |

|

|

|

Writing Your Summary

Once you have read and re-read your text at least once, taking notes and reflecting along the way, you are ready to start writing a summary. Before starting, consider your rhetorical situation: What are you trying to accomplish (purpose) with your summary? What details and ideas (subject) are important for your reader (audience) to know? Should you assume that they have also read the text you’re summarizing? I’m thinking back here to the “Previously on…” idea: TV series don’t include everything from a prior episode; they focus instead on moments that set up the events of their next episode. You too should choose your content in accordance with your rhetorical situation.

I encourage you to start off by articulating the “key” idea or ideas from the text in one or two sentences. Focus on clarity of language: start with simple word choice, a single idea, and a straightforward perspective so that you establish a solid foundation.

The authors support feminist theories and practices that are critical of racism and other oppressions.

Then, before that sentence, write one or two more sentences that introduce the title of the text, its authors, and its main concerns or interventions. Revise your key idea sentence as necessary.

In “Why Our Feminism Must Be Intersectional (And 3 Ways to Practice It),” Jarune Uwuajaren and Jamie Utt critique what is known as ‘white feminism.’ They explain that sexism is wrapped up in racism, Islamophobia, heterosexism, transphobia, and other systems of oppression. The authors support feminist theories and practices that recognize intersectionality.

In most summary assignments, though, you will be expected to draw directly from the article itself by using direct quotes or paraphrases in addition to your own summary.

Paraphrase, Summary, and Direct Quotes

Whether you’re writing a summary or broaching your analysis, using support from the text will help you clarify ideas, demonstrate your understanding, or further your argument, among other things. Three distinct methods, which Bruce Ballenger refers to as “The Notetaker’s Triad,” will allow you to process and reuse information from your focus text. 1

A direct quote might be most familiar to you: using quotation marks (“ ”) to indicate the moments that you’re borrowing, you reproduce an author’s words verbatim in your own writing. Use a direct quote if someone else wrote or said something in a distinctive or particular way and you want to capture their words exactly.

Direct quotes are good for establishing ethos and providing evidence. In a text wrestling essay, you will be expected to use multiple direct quotes: in order to attend to specific language, you will need to reproduce segments of that language in your analysis.

Paraphrasing is similar to the process of summary. When we paraphrase, we process information or ideas from another person’s text and put it in our own words. The main difference between paraphrase and summary is scope: if summarizing means rewording and condensing, then paraphrasing means rewording without drastically altering length. However, paraphrasing is also generally more faithful to the spirit of the original; whereas a summary requires you to process and invites your own perspective, a paraphrase ought to mirror back the original idea using your own language.

Paraphrasing is helpful for establishing background knowledge or general consensus, simplifying a complicated idea, or reminding your reader of a certain part of another text. It is also valuable when relaying statistics or historical information, both of which are usually more fluidly woven into your writing when spoken with your own voice.

Summary , as discussed earlier in this chapter, is useful for “broadstrokes” or quick overviews, brief references, and providing plot or character background. When you summarize, you reword and condense another author’s writing. Be aware, though, that summary also requires individual thought: when you reword, it should be a result of you processing the idea yourself, and when you condense, you must think critically about which parts of the text are most important. As you can see in the example below, one summary shows understanding and puts the original into the author’s own words; the other summary is a result of a passive rewording, where the author only substituted synonyms for the original.

Original Quote: “On Facebook, what you click on, what you share with your ‘friends’ shapes your profile, preferences, affinities, political opinions and your vision of the world. The last thing Facebook wants is to contradict you in any way” (Filloux).

| Summary example | Pass/Fail |

| On Facebook, the things you click on and share forms your profile, likings, sympathies, governmental ideas and your image of society. Facebook doesn’t want to contradict you at all (Filloux). |

|

| When you interact with Facebook, you teach the algorithms about yourself. Those algorithms want to mirror back your beliefs (Filloux).

|

|

Each of these three tactics should support your summary or analysis: you should integrate quotes, paraphrases, and summary with your own writing. Below, you can see three examples of these tools. Consider how the direct quote, the paraphrase, and the summary each could be used to achieve different purposes.

Original Passage

It has been suggested (again rather anecdotally) that giraffes do communicate using infrasonic vocalizations (the signals are verbally described to be similar—in structure and function—to the low-frequency, infrasonic “rumbles” of elephants). It was further speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production. Moreover, particular neck movements (e.g. the neck stretch) are suggested to be associated with the production of infrasonic vocalizations. 2

| Some zoological experts have pointed out that the evidence for giraffe hums has been “rather anecdotally” reported (Baotic et al. 3). However, some scientists have “speculated that the extensive frontal sinus of giraffes acts as a resonance chamber for infrasound production” (Ibid. 3). | Giraffes emit a low-pitch noise; some scientists believe that this can be used for communication with other members of the social group, but others are skeptical because of the dearth of research on giraffe noises. According to Baotic et al., the anatomy of the animal suggests that they may be making deliberate and specific noises (3). | Baotic et al. conducted a study on giraffe hums in response to speculation that these noises are used deliberately for communication.

|

The examples above also demonstrate additional citation conventions worth noting:

- A parenthetical in-text citation is used for all three forms. (In MLA format, this citation includes the author’s last name and page number.) The purpose of an in-text citation is to identify key information that guides your reader to your Works Cited page (or Bibliography or References, depending on your format).

- If you use the author’s name in the sentence, you do not need to include their name in the parenthetical citation.

- If your material doesn’t come from a specific page or page range, but rather from the entire text, you do not need to include a page number in the parenthetical citation.

- If there are many authors (generally more than three), you can use “et al.” to mean “and others.”

- If you cite the same source consecutively in the same paragraph (without citing any other sources in between), you can use “Ibid.” to mean “same as the last one.”

In Chapter Six, we will discuss integrating quotes, summaries, and paraphrases into your text wrestling analysis. Especially if you are writing a summary that requires you to use direct quotes, I encourage you to jump ahead to “Synthesis: Using Evidence to Explore Your Thesis” in that chapter.

Summary and Response: TV Show or Movie

Practice summary and response using a movie or an episode of a television show. (Although it can be more difficult with a show or movie you already know and like, you can apply these skills to both familiar and unfamiliar texts.)

Watch it once all the way through, taking notes using the double-column structure above.

Watch it once more, pausing and rewinding as necessary, adding additional notes.

Write one or two paragraphs summarizing the episode or movie as objectively as possible. Try to include the major plot points, characters, and conflicts.

Write a paragraph that transitions from summary to response: what were your reactions to the episode or movie? What do you think produced those reactions? What seems troubling or problematic? What elements of form and language were striking? How does the episode or movie relate to your lived experiences?

Everyone’s a Critic: Food Review

Food critics often employ summary and response with the purpose of reviewing restaurants for potential customers. You can give it a shot by visiting a restaurant, your dining hall, a fast-food joint, or a food cart. Before you get started, consider reading some food and restaurant reviews from your local newspaper. (Yelp often isn’t quite thorough enough.)

Bring a notepad to your chosen location and take detailed notes on your experience as a patron. Use descriptive writing techniques (see Chapter One), to try to capture the experience.

What happens as you walk in? Are you greeted? What does it smell like? What are your immediate reactions?

Describe the atmosphere. Is there music? What’s the lighting like? Is it slow, or busy?

Track the service. How long before you receive the attention you need? Is that attention appropriate to the kind of food-service place you’re in?

Record as many details about the food you order as possible.

After your dining experience, write a brief review of the restaurant, dining hall, fast-food restaurant, or food cart. What was it like, specifically? Did it meet your expectations? Why or why not? What would you suggest for improvement? Would you recommend it to other diners like you?

Digital Media Summary and Mini-Analysis

For this exercise, you will study a social media feed of your choice. You can use your own or someone else’s Facebook feed, Twitter feed, or Instagram feed. Because these feeds are tailored to their respective user’s interests, they are all unique and represent something about the user.

After closely reviewing at least ten posts, respond to the following questions in a brief essay:

What is the primary medium used on this platform (e.g, images, text, video, etc.)?

What recurring ideas, themes, topics, or preoccupations do you see in this collection? Provide examples.

Do you see posts that deviate from these common themes?

What do the recurring topics in the feed indicate about its user? Why?

Bonus: What ads do you see popping up? How do you think these have been geared toward the user?

Model Texts by Student Authors

Maggie as the focal point 3.

Shanna Greene Benjamin attempts to resolve Toni Morrison’s emphasis on Maggie in her short story “Recitatif”. While many previous scholars focus on racial codes, and “the black-and-white” story that establishes the racial binary, Benjamin goes ten steps further to show “the brilliance of Morrison’s experiment” (Benjamin 90). Benjamin argues that Maggie’s story which is described through Twyla’s and Roberta’s memories is the focal point of “Recitatif” where the two protagonists have a chance to rewrite “their conflicting versions of history” (Benjamin 91). More so, Maggie is the interstitial space where blacks and whites can engage, confront America’s racialized past, rewrite history, and move forward.

Benjamin highlights that Maggie’s story is first introduced by Twyla, labeling her recollections as the “master narrative” (Benjamin 94). Although Maggie’s story is rebutted with Roberta’s memories, Twyla’s version “represent[s] the residual, racialized perspectives” stemming from America’s past (Benjamin 89). Since Maggie is a person with a disability her story inevitably becomes marginalized, and utilized by both Twyla and Roberta for their own self-fulfilling needs, “instead of mining a path toward the truth” (Benjamin 97). Maggie is the interstitial narrative, which Benjamin describes as a space where Twyla and Roberta, “who represent opposite ends of a racial binary”, can come together to heal (Benjamin 101). Benjamin also points out how Twyla remembers Maggie’s legs looking “like parentheses” and relates the shape of parentheses, ( ), to self-reflection (Morrison 141). Parentheses represent that inward gaze into oneself, and a space that needs to be filled with self-reflection in order for one to heal and grow. Twyla and Roberta create new narratives of Maggie throughout the story in order to make themselves feel better about their troubled past. According to Benjamin, Maggie’s “parenthetical body” is symbolically the interstitial space that “prompts self-reflection required to ignite healing” (Benjamin 102). Benjamin concludes that Morrison tries to get the readers to engage in America’s past by eliminating and taking up the space between the racial binary that Maggie represents.

Not only do I agree with Benjamin’s stance on “Recitatif”, but I also disapprove of my own critical analysis of “Recitatif.” I made the same mistakes that other scholars have made regarding Morrison’s story; we focused on racial codes and the racial binary, while completely missing the interstitial space which Maggie represents. Although I did realize Maggie was of some importance, I was unsure why so I decided to not focus on Maggie at all. Therefore, I missed the most crucial message from “Recitatif” that Benjamin hones in on.

Maggie is brought up in every encounter between Twyla and Roberta, so of course it makes sense that Maggie is the focal point in “Recitatif”. Twyla and Roberta project themselves onto Maggie, which is why the two women have a hard time figuring out “‘What the hell happened to Maggie’” (Morrison 155). Maggie also has the effect of bringing the two women closer together, yet at times causing them to be become more distant. For example, when Twyla and Roberta encounter one another at the grocery store, Twyla brings up the time Maggie fell and the “gar girls laughed at her”, while Roberta reminds her that Maggie was in fact pushed down (Morrison 148). Twyla has created a new, “self-serving narrative[ ]” as to what happened to Maggie instead of accepting what has actually happened, which impedes Twyla’s ability to self-reflect and heal (Benjamin 102). If the two women would have taken up the space between them to confront the truths of their past, Twyla and Roberta could have created a “cooperative narrative” in order to mend.

Maggie represents the interstitial space that lies between white and black Americans. I believe this is an ideal space where the two races can come together to discuss America’s racialized past, learn from one another, and in turn, understand why America is divided as such. If white and black America jumped into the space that Maggie defines, maybe we could move forward as a country and help one another succeed. When I say “succeed”, I am not referring to the “American dream” because that is a false dream created by white America. “Recitatif” is not merely what characteristics define which race, it is much more than. Plus, who cares about race! I want America to be able to benefit and give comfort to every citizen whatever their “race” may be. This is time where we need black and white America to come together and fight the greater evil, which is the corruption within America’s government.

Teacher Takeaways

“This student’s summary of Benjamin’s article is engaging and incisive. Although the text being summarized seems very complex, the student clearly articulates the author’s primary claims, which are a portrayed as an intervention in a conversation (i.e., a claim that challenges what people might think beforehand). The author is also honest about their reactions to the text, which I enjoy, but they seem to lose direction a bit toward the end of the paper. Also, given a chance to revise again, this student should adjust the balance of quotes and paraphrases/ summaries: they use direct quotes effectively, but too frequently.”– Professor Wilhjelm

Works Cited

Benjamin, Shanna Greene. “The Space That Race Creates: An Interstitial Analysis of Toni Morrison’s ‘Recitatif.’” Studies in American Fiction , vol. 40, no. 1, 2013, pp. 87–106. Project Muse , doi: 10.1353/saf.2013.0004 .

Morrison, Toni. “Recitatif.” The Norton Introduction to Literature, Portable 12th edition, edited by Kelly J. Mays, W.W. Norton & Company, 2017, pp. 138-155.

Pronouns & Bathrooms 4

The article “Pronouns and Bathrooms: Supporting Transgender Students,” featured on Edutopia, was written to give educators a few key points when enacting the role of a truly (gender) inclusive educator. It is written specifically to high-school level educators, but I feel that almost all of the rules that should apply to a person who is transgender or gender-expansive at any age or grade level. The information is compiled by several interviews done with past and present high school students who identify with a trans-identity. The key points of advice stated are supported by personal statements made by past or present students that identify with a trans-identity.

The first point of advice is to use the student’s preferred name and/or pronoun. These are fundamental to the formation of identity and demand respect. The personal interview used in correlation with the advice details how the person ended up dropping out of high school after transferring twice due to teachers refusing to use their preferred name and pronoun. This is an all-too-common occurrence. The trans community recommend that schools and administrators acquire updated gender-inclusive documentation and update documentation at the request of the student to avoid misrepresentation and mislabeling. When you use the student’s preferred name and pronoun in and out of the classroom you are showing the student you sincerely care for their well-being and the respect of their identity.

The second and other most common recommendation is to make “trans-safe” (single-use, unisex or trans-inclusive) bathrooms widely available to students. Often these facilities either do not exist at all or are few-and-far-between, usually inconveniently located, and may not even meet ADA standards. This is crucial to insuring safety for trans-identified students.

Other recommendations are that schools engage in continual professional development training to insure that teachers are the best advocates for their students. Defend and protect students from physical and verbal abuse. Create a visibly welcoming and supportive environment for trans-identified students by creating support groups, curriculum and being vocal about your ally status.

The last piece of the article tells us a person who is trans simply wants to be viewed as human—a fully actualized human. I agree whole-heartedly. I believe that everyone has this desire. I agree with the recommendations of the participants that these exhibitions of advocacy are indeed intrinsic to the role of gender-expansive ally-ship,

While they may not be the most salient of actions of advocacy, they are the most foundational parts. These actions are the tip of the iceberg, but they must be respected. Being a true ally to the gender-expansive and transgender communities means continually expanding your awareness of trans issues. I am thankful these conversations are being had and am excited for the future of humanity.

“The author maintains focus on key arguments and their own understanding of the text’s claims. By the end of the summary, I have a clear sense of the recommendations the authors make for supporting transgender students. However, this piece could use more context at the beginning of each paragraph: the student could clarify the logical progression that builds from one paragraph to the next. (The current structure reads more like a list.) Similarly, context is missing in the form of citations, and no author is ever mentioned. Overall this author relies a bit too much on summary and would benefit from using a couple direct quotations to give the reader a sense of the author’s language and key ideas. In revision, this author should blend summaries, paraphrases, and quotes to develop this missing context.”– Professor Dannemiller

Wiggs, Blake. “ Pronouns and Bathrooms: Supporting Transgender Students .” Edutopia , 28 September 2015

Education Methods: Banking vs. Problem-Posing 5

Almost every student has had an unpleasant experience with an educator. Many times this happens due to the irrelevant problems posed by educators and arbitrary assignments required of the student. In his chapter from Pedagogy of the Oppressed , Paulo Freire centers his argument on the oppressive and unsuccessful banking education method in order to show the necessity of a problem-posing method of education.

Freire begins his argument by intervening into the conversation regarding teaching methods and styles of education, specifically responding in opposition to the banking education method, a method that “mirrors the oppressive society as a whole” (73). He describes the banking method as a system of narration and depositing of information into students like “containers” or “receptacles” (72). He constructs his argument by citing examples of domination and mechanical instruction as aspects that create an assumption of dichotomy, stating that “a person is merely in the world, not with the world or with others” (75). Freire draws on the reader’s experiences with this method by providing a list of banking attitudes and practices including “the teacher chooses and enforces his choices, and the students comply” (73), thus allowing the reader to connect the subject with their lived experiences.

In response to the banking method, Freire then advocates for a problem-posing method of education comprised of an educator constantly reforming her reflections in the reflection of the students. He theorizes that education involves a constant unveiling of reality, noting that “they come to see the world not as a static reality but as a reality in process, in transformation” (83). Thus, the problem-posing method draws on discussion and collaborative communication between students and educator. As they work together, they are able to learn from one another and impact the world by looking at applicable problems and assignments, which is in direct opposition of the banking method.

While it appears that Freire’s problem-posing method is more beneficial to both the student and educator, he fails to take into account the varying learning styles of te students, as well as the teaching abilities of the educators. He states that through the banking method, “the student records, memorizes, and repeats these phrases without perceiving what four times four really means, or realizing the true significance” (71). While this may be true for many students, some have an easier time absorbing information when it is given to them in a more mechanical fashion. The same theory applies to educators as well. Some educators may have a more difficult time communicating through the problem-posing method. Other educators may not be as willing to be a part of a more collaborative education method.

I find it difficult to agree with a universal method of education, due to the fact that a broad method doesn’t take into consideration the varying learning and communication styles of both educator and student. However, I do agree with Freire on the basis that learning and education should be a continuous process that involves the dedication of both student and educator. Students are their own champions and it takes a real effort to be an active participant in one’s own life and education. It’s too easy to sit back and do the bare minimum, or be an “automaton” (74). To constantly be open to learning and new ideas, to be a part of your own education, is harder, but extremely valuable.

As a student pursuing higher education, I find this text extremely reassuring. The current state of the world and education can seem grim at times, but after reading this I feel more confident that there are still people who feel that the current systems set in place are not creating students who can critically think and contribute to the world. Despite being written forty years ago, Freire’s radical approach to education seems to be a more humanistic style, one where students are thinking authentically, for “authentic thinking is concerned with reality” (77). Problem-posing education is one that is concerned with liberation, opposed to oppression. The banking method doesn’t allow for liberation, for “liberation is a praxis: the action and reflection of men and women upon their world in order to transform it” (79). Educational methods should prepare students to be liberators and transformers of the world, not containers to receive and store information.

“I love that this student combines multiple forms of information (paraphrases, quotes, and summaries) with their own reactions to the text. By using a combined form of summary, paraphrase, and quote, the student weaves ideas from the text together to give the reader a larger sense of the author’s ideas and claims. The student uses citations and signal phrases to remind us of the source. The student also does a good job of keeping paragraphs focused, setting up topic sentences and transitions, and introducing ideas that become important parts of their thesis. On the other hand, the reader could benefit from more explanation of some complex concepts from the text being analyzed, especially if the author assumes that the reader isn’t familiar with Freire. For example, the banking method of education is never quite clearly explained and the reader is left to derive its meaning from the context clues the student provides. A brief summary or paraphrase of this concept towards the beginning of the essay would give us a better understanding of the contexts the student is working in.”– Professor Dannemiller

Freire, Paulo. “Chapter 2.” Pedagogy of the Oppressed , translated by Myra Bergman Ramos, 30 th Anniversary Edition, Continuum, 2009, pp. 71-86.

You Snooze, You Peruse 6

This article was an interesting read about finding a solution to the problem that 62% of high school students are facing — chronic sleep deprivation (less than 8 hours on school nights). While some schools have implemented later start times, this article argues for a more unique approach. Several high schools in Las Cruces, New Mexico have installed sleeping pods for students to use when needed. They “include a reclined chair with a domed sensory-reduction bubble that closes around one’s head

and torso” and “feature a one-touch start button that activates a relaxing sequence of music and soothing lights” (Conklin). Students rest for 20 minutes and then go back to class. Some of the teachers were concerned about the amount of valuable class time students would miss while napping, while other teachers argued that if the students are that tired, they won’t be able to focus in class anyway. Students who used the napping pods reported they were effective in restoring energy levels and reducing stress. While that is great, there was concern from Melissa Moore, a pediatric sleep specialist, that napping during the day would cause students to sleep less during that “all-important nighttime sleep.”

Sleep deprivation is a serious issue in high school students. I know there are a lot of high school students that are very involved in extra-curricular activities like I was. I was on student council and played sports year-round, which meant most nights I got home late, had hours of homework, and almost never got enough sleep. I was exhausted all the time, especially during junior and senior year. I definitely agree that there is no point in students sitting in class if they’re so tired they can barely stay awake. However, I don’t know if sleeping pods are the best solution. Sure, after a 20-minute nap students feel a little more energetic, but I don’t think this is solving the chronic issue of sleep deprivation. A 20-minute nap isn’t solving the problem that most students aren’t getting 8 hours of sleep, which means they aren’t getting enough deep sleep (which usually occurs between hours 6-8). Everyone needs these critical hours of sleep, especially those that are still growing and whose brains are still developing. I think it would be much more effective to implement later start times. High school students aren’t going to go to bed earlier, that’s just the way it is. But having later start times gives them the opportunity to get up to an extra hour of sleep, which can make a huge difference in the overall well-being of students, as well as their level of concentration and focus in the classroom.

“I appreciate that this author has a clear understanding of the article which they summarize, and in turn are able to take a clear stance of qualification (‘Yes, but…’). However, I would encourage this student to revisit the structure of their summary. They’ve applied a form that many students fall back on instinctively: the first half is ‘What They Say’ and the second half is ‘What I Say.’ Although this can be effective, I would rather that the student make this move on the sentence level so that paragraphs are organized around ideas, not the sources of those ideas.”– Professor Wilhjelm

Conklin, Richard. “ You Snooze, You Peruse: Some Schools Turn to Nap Time to Recharge Students .” Education World, 2017 .

Bloom, Benjamin S., et al. Tax onomy of Educational Objectives: T he Classification of Educational Goals . D. McKay Co., 1969.

Also of note are recent emphases to use Bloom’s work as a conceptual model, not a hard-and-fast, infallible rule for cognition. Importantly, we rarely engage only one kind of thinking, and models like this should not be used to make momentous decisions; rather, they should contribute to a broader, nuanced understanding of human cognition and development.

In consideration of revised versions Bloom’s Taxonomy and the previous note, it can be mentioned that this process necessarily involves judgment/evaluation; using the process of interpretation, my analysis and synthesis require my intellectual discretion.

Mays, Kelly J. “The Literature Essay.” The Norton Introduction to Literature , Portable 12th edition, Norton, 2017, pp. 1255-1278.

“Developing a Thesis.” Purdue OWL , Purdue University, 2014, https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/616/02/ . [Original link has expired. See Purdue OWL’s updated version: Developing a Thesis ]

Read more advice from the Purdue OWL relevant to close reading at https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/section/4/17/ .

One particularly useful additional resource is the text “Annoying Ways People Use Sources,” externally linked in the Additional Recommended Resources appendix of this book.

Essay by an anonymous student author, 2014. Reproduced with permission from the student author.

This essay is a synthesis of two students’ work. One of those students is Ross Reaume, Portland State University, 2014, and the other student wishes to remain anonymous. Reproduced with permission from the student authors.

Essay by Marina, who has requested her last name not be included. Portland Community College, 2018. Reproduced with permission from the student author.

the verbatim use of another author’s words. Can be used as evidence to support your claim, or as language to analyze/close-read to demonstrate an interpretation or insight.

author reiterates a main idea, argument, or detail of a text in their own words without drastically altering the length of the passage(s) they paraphrase. Contrast with summary.

a mode of writing that values the reader’s experience of and reactions to a text.

a rhetorical mode in which an author reiterates the main ideas, arguments, and details of a text in their own words, condensing a longer text into a smaller version. Contrast with paraphrase.

EmpoWORD: A Student-Centered Anthology and Handbook for College Writers Copyright © 2018 by Shane Abrams is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

5 Steps to Write a Great Analytical Essay

General Education

Do you need to write an analytical essay for school? What sets this kind of essay apart from other types, and what must you include when you write your own analytical essay? In this guide, we break down the process of writing an analytical essay by explaining the key factors your essay needs to have, providing you with an outline to help you structure your essay, and analyzing a complete analytical essay example so you can see what a finished essay looks like.

What Is an Analytical Essay?

Before you begin writing an analytical essay, you must know what this type of essay is and what it includes. Analytical essays analyze something, often (but not always) a piece of writing or a film.

An analytical essay is more than just a synopsis of the issue though; in this type of essay you need to go beyond surface-level analysis and look at what the key arguments/points of this issue are and why. If you’re writing an analytical essay about a piece of writing, you’ll look into how the text was written and why the author chose to write it that way. Instead of summarizing, an analytical essay typically takes a narrower focus and looks at areas such as major themes in the work, how the author constructed and supported their argument, how the essay used literary devices to enhance its messages, etc.

While you certainly want people to agree with what you’ve written, unlike with persuasive and argumentative essays, your main purpose when writing an analytical essay isn’t to try to convert readers to your side of the issue. Therefore, you won’t be using strong persuasive language like you would in those essay types. Rather, your goal is to have enough analysis and examples that the strength of your argument is clear to readers.

Besides typical essay components like an introduction and conclusion, a good analytical essay will include:

- A thesis that states your main argument

- Analysis that relates back to your thesis and supports it

- Examples to support your analysis and allow a more in-depth look at the issue

In the rest of this article, we’ll explain how to include each of these in your analytical essay.

How to Structure Your Analytical Essay

Analytical essays are structured similarly to many other essays you’ve written, with an introduction (including a thesis), several body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Below is an outline you can follow when structuring your essay, and in the next section we go into more detail on how to write an analytical essay.

Introduction

Your introduction will begin with some sort of attention-grabbing sentence to get your audience interested, then you’ll give a few sentences setting up the topic so that readers have some context, and you’ll end with your thesis statement. Your introduction will include:

- Brief background information explaining the issue/text

- Your thesis

Body Paragraphs

Your analytical essay will typically have three or four body paragraphs, each covering a different point of analysis. Begin each body paragraph with a sentence that sets up the main point you’ll be discussing. Then you’ll give some analysis on that point, backing it up with evidence to support your claim. Continue analyzing and giving evidence for your analysis until you’re out of strong points for the topic. At the end of each body paragraph, you may choose to have a transition sentence that sets up what the next paragraph will be about, but this isn’t required. Body paragraphs will include:

- Introductory sentence explaining what you’ll cover in the paragraph (sort of like a mini-thesis)

- Analysis point

- Evidence (either passages from the text or data/facts) that supports the analysis

- (Repeat analysis and evidence until you run out of examples)

You won’t be making any new points in your conclusion; at this point you’re just reiterating key points you’ve already made and wrapping things up. Begin by rephrasing your thesis and summarizing the main points you made in the essay. Someone who reads just your conclusion should be able to come away with a basic idea of what your essay was about and how it was structured. After this, you may choose to make some final concluding thoughts, potentially by connecting your essay topic to larger issues to show why it’s important. A conclusion will include:

- Paraphrase of thesis

- Summary of key points of analysis

- Final concluding thought(s)

5 Steps for Writing an Analytical Essay

Follow these five tips to break down writing an analytical essay into manageable steps. By the end, you’ll have a fully-crafted analytical essay with both in-depth analysis and enough evidence to support your argument. All of these steps use the completed analytical essay in the next section as an example.

#1: Pick a Topic