National Archives News

The Flu Pandemic of 1918

Red Cross workers make anti-influenza masks for soldiers, Boston, Massachusetts. (National Archives Identifier 45499341 )

Before COVID-19, the most severe pandemic in recent history was the 1918 influenza virus, often called “the Spanish Flu.” The virus infected roughly 500 million people—one-third of the world’s population—and caused 50 million deaths worldwide (double the number of deaths in World War I). In the United States, a quarter of the population caught the virus, 675,000 died, and life expectancy dropped by 12 years. With no vaccine to protect against the virus, people were urged to isolate, quarantine, practice good personal hygiene, and limit social interaction. Until February 2020, the 1918 epidemic was largely overlooked in the teaching of American history, despite the ample documentation at the National Archives and elsewhere of the disease and its devastation. The 100-year-old pictures from 1918 that just months ago seemed quaint and dated now seem oddly prescient. We make these records more widely available in hopes that they contain lessons about what to expect over the coming months and ideas about ways to avoid a repeat and prepare for what may follow.

Online Exhibit

A selection of photographs and documents from the National Archives' nationwide holdings tell the story of the 1918 influenza pandemic.

Photographs

(Click image to view gallery)

Images from the 1918 Flu Pandemic

Female clerks in New York City wear masks at work. (National Archives Identifier 45499337 )

Department of the Navy: Precautions Against Influenza. (National Archives Identifier 6861947 )

Traffic "cop" in New York City wearing gauze mask. (National Archives Identifier 45499301 )

New York City "conductorettes" wearing masks. (National Archives Identifier 45499323 )

Letter carrier in New York City wearing mask. (National Archives Identifier 45499319 )

To prevent the spread of Spanish Influenza, Cincinnati barbers are wearing masks. (National Archives Identifier 45499317 )

Additional Photographs

- Red Cross volunteer nurses in Eureka, CA

- Red Cross Women’s Motor Corps aids injured patients

- Red Cross workers in Seattle

- Street cleaner in mask

- Boston Red Cross workers making masks for soldiers

- Female elevator operator in New York City

- Eberts Field, Lonoke, AR: Convalescent influenza patients in hospital overflow space

- Emergency hospital, Brookline, MA, to care for influenza cases

- Fighting influenza in Seattle: Flu serum injection

- A nurse wearing a mask fills water from a pitcher

- Mother and daughter work on a quilt for soldiers

- Red Cross Motor Corps on duty

- San Francisco police court meets in open air for influenza prevention

Author Lecture

Dr. Jeremy Brown, Director of Emergency Care Research, National Institutes of Health, spoke about his book Influenza: The Hundred-Year Hunt to Cure the Deadliest Disease in History, at the National Archives in Washington, DC, on March 5, 2019.

Archival Film

Nurses make bandages for flu epidemic (stock newsreel footage from CBS)

Blogs and Social Media Posts

Forward with Roosevelt: One of the Millions: FDR and the Flu Pandemic of 1918–1920

Text Message: The “Spanish Flu” Pandemic of 1918–1919: A Death in Philadelphia

Pieces of History: Pandemic Nursing: The 1918 Influenza Outbreak

Pieces of History: Influenza Epidemic 1918—“Wear a mask and save your life”

Pieces of History: Gesundheit!

Unwritten Record: The 1918 Influenza Pandemic

Today's Document: Precautions Against Influenza

Tumblr: 1918 to COVID-19

Tumblr: Influenza Epidemic 1918—“Wear a mask and save your life”

For Educators

Influenza Directive from DC re: treatment and procedures , 9/26/1918

Influenza Prophylaxis Memo from Third Naval District Medical Officer

Documents Related to the Flu Pandemic of 1918

Memo Re: Sanitary Precautions, 9/12/1918

Additional primary sources and educational resources from DocsTeach

At the Presidential Libraries

Truman Library: Letter from Harry to Bess , referencing the influenza epidemic, and expressing relief that Bess has recovered from it.

Ford Library: Remarks Upon the Signing of National Swine Flu Immunization Program of 1976

Ford Library: President Asks Congress for $135 Million for Swine Flu Vaccine Ford Library: Fact Sheet on Swine Influenza Immunization Program

George W. Bush Library: Pandemic Flu: Preparing and Protecting against Avian Influenza

Barack Obama Library: Declaration of Nat’l Emergency - 2009 H1N1 Influenza Pandemic

Barack Obama Library: Press Briefing On Swine Influenza

Posts Related to COVID-19

National Archives COVID-19 Updates

AOTUS Blog: National Archives Operations During COVID-19: Mission Critical Functions Continue

AOTUS Blog: National Archives Donates Protective Gear for COVID-19 Response

National Archives News: National Personnel Records Center Continues Serving Veterans During COVID-19 Pandemic

National Archives News: National Archives Donates Protective Gear for COVID-19 Response

Office of the Federal Register: COVID-19 Procedures

Press Release: Information on NHPRC and COVID-19

Records Management: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Records Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

History Hit Story of England: Making of a Nation

- 20th Century

10 Facts About the Deadly 1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic

Léonie Chao-Fong

12 feb 2020.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, also known as the Spanish flu, was the deadliest epidemic in world history.

An estimated 500 million worldwide were infected, and the death toll was anywhere from between 20 to 100 million.

Influenza, or flu, is a virus that attacks the respiratory system. It is highly contagious: when an infected person coughs, sneezes or talks, droplets are transmitted into the air and can be inhaled by anyone nearby.

A person can also be infected by touching something with the flu virus on it, and then touching their mouth, eyes or nose.

Although a pandemic of the influenza virus had already killed thousands in 1889, it was not until 1918 that the world discovered how deadly the flu could be.

Here are 10 facts about the 1918 Spanish flu.

1. It struck in three waves across the world

Three pandemic waves: weekly combined influenza and pneumonia mortality, United Kingdom, 1918–1919 (Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ).

The first wave of the 1918 pandemic took place in the spring of that year, and was generally mild.

Those infected experienced typical flu symptoms – chills, fever, fatigue – and usually recovered after several days. The number of reported deaths was low.

In the autumn of 1918, the second wave appeared – and with a vengeance.

Victims died within hours or days of developing symptoms. Their skin would turn blue, and their lungs would fill with fluids, causing them to suffocate.

In the space of one year, the average life expectancy in the United States plummeted by a dozen years.

A third, more moderate, wave hit in the spring of 1919. By the summer it had subsided.

2. Its origins are unknown to this day

Demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C. (Credit: Library of Congress ).

The 1918 flu was first observed in Europe, America and parts of Asia, before rapidly spreading across every part of the world within a matter of months.

It remains unknown where the particular strain of influence – the first pandemic involving the H1N1 influenza virus – came from.

There is some evidence to suggest that the virus came from a bird or farm animal in the American Midwest, travelling among the animal species before mutating into a version that took hold in the human population.

Some claimed the epicentre was a military camp in Kansas, and that it spread through the US and into Europe via the troops who travelled east to fight in the First World War.

Others believe it originated in China, and was transported by labourers heading for the western front.

3. It did not come from Spain (despite the nickname)

Despite its colloquial name, the 1918 flu did not originate from Spain.

The British Medical Journal referred to the virus as “Spanish flu” because Spain was hit hard by the disease. Even Spain’s king, Alfonso XIII, reportedly contracted the flu.

In addition, Spain was not subject to the wartime news censorship rules that affected other European countries.

In response, Spaniards named the illness the “Naples soldier”. The German army called it “ Blitzkatarrh ”, and British troops referred to it as “Flanders grippe” or the “Spanish lady”.

U.S. Army Camp Hospital No. 45, Aix-Les-Bains, France.

4. There were no drugs or vaccines to treat it

When the flu hit, doctors and scientists were unsure what caused it or how to treat it. At the time, there were no effective vaccines or antivirals to treat the deadly strain.

People were advised to wear masks, avoid shaking hands, and to stay indoors. Schools, churches, theatres and businesses were shuttered, libraries put a halt on lending books and quarantines were imposed across communities.

Bodies began to pile up in makeshift morgues, while hospitals quickly became overloaded with flu patients. Doctors, health staff and medical students became infected.

Demonstration at the Red Cross Emergency Ambulance Station in Washington, D.C (Credit: Library of Congress ).

To complicate things further, the Great War had left countries with a shortage of physicians and health workers.

It was not until the 1940s that the first licensed flu vaccine appeared in the US. By the following decade, vaccines were routinely produced to help control and prevent future pandemics.

5. It was particularly deadly for young and healthy people

Volunteer nurses from the American Red Cross tending influenza sufferers in the Oakland Auditorium, Oakland, California (Credit: Edward A. “Doc” Rogers ).

Most influenza outbreaks only claim as fatalities juveniles, the elderly, or people who are already weakened. Today, flu is especially dangerous for under 5-year-olds and those over 75.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, however, affected completely healthy and strong adults between 20 and 40 years of age – including millions of World War One soldiers.

Surprisingly, children and those with weaker immune systems were spared from death. Those aged 75 and above had the lowest death rate of all.

6. The medical profession tried to play down its severity

In the summer of 1918, the Royal College of Physicians claimed the flu was no more threatening than the “Russian flu” of 1189-94.

The British Medical Journal accepted that overcrowding on transport and in the workplace was necessary for the war effort, and implied that the “inconvenience” of the flu should be quietly borne.

Individual doctors also did not fully comprehend the severity of the disease, and tried to play it down to avoid spreading anxiety.

In Egremont, Cumbria, which saw an appalling death rate, the medical officer requested the rector stop ringing the church bells for each funeral because he wanted to “keep people cheerful”.

The press did likewise. ‘The Times’ suggested that it was probably a result of “the general weakness of nerve-power known as war-weariness”, while ‘The Manchester Guardian’ scorned protective measures saying:

Women are not going to wear ugly masks.

7. 25 million people died in the first 25 weeks

As the second wave of the autumn hit, the flu epidemic spiralled out of control. In most cases, haemorrhages in the nose and lungs killed victims within three days.

International ports – usually the first places in a country to be infected – reported serious problems. In Sierra Leone, 500 out of 600 dock workers fell too sick to work.

Epidemics were quickly seen in Africa, India and the Far East. In London, the spread of the virus became far more deadly and contagious as it mutated.

Chart showing mortality from the 1918 influenza pandemic in the US and Europe (Credit: National Museum of Health and Medicine ).

10% of the entire population of Tahiti died within three weeks. In Western Samoa, 20% of the population died.

Each division of the US armed services reported hundreds of deaths each week. After the Liberty Loan parade in Philadelphia on 28 September, thousands of people became infected.

By the summer of 1919, those who were infected had either died or developed immunity, and the epidemic finally came to an end.

8. It reached almost every single part of the world

The 1918 epidemic was of a truly global scale . It infected 500 million people across the world, including those on remote Pacific Islands and in the Arctic.

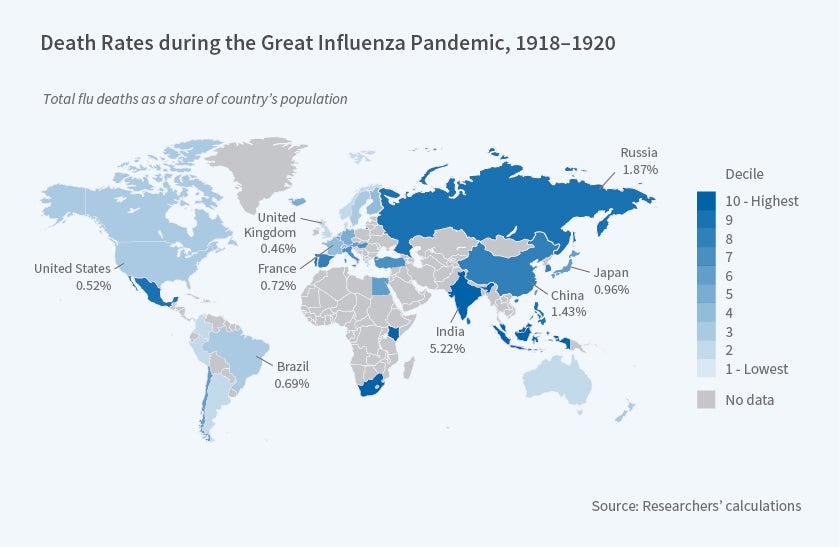

In Latin America, 10 out of every 1,000 people died; in Africa, it was 15 per 1,000. In Asia, the death toll reached as high as 35 in every 1,000.

In Europe and America, troops travelling by boat and train took the flu into cities, from where it spread to the countryside.

Only St Helena in the South Atlantic and a handful of South Pacific islands did not report an outbreak.

9. The exact death toll is impossible to know

Memorial to the thousands of victims of New Zealand’s 1918 epidemic (Credit: russellstreet / 1918 Influenza Epidemic Site ).

The estimated death toll attributed to the 1918 flu epidemic is usually at 20 million to 50 million victims worldwide. Other estimates run as high as 100 million victims – around 3% of the world’s population.

However it is impossible to know what the exact death toll was, due to the lack of accurate medical record-keeping in many infected places.

The epidemic wiped out entire families, destroyed whole communities and overwhelmed funeral parlours across the world.

10. It killed more people than World War One combined

More American soldiers died from the 1918 flu than were killed in battle during the First World War. In fact, the flu claimed more lives than all of the World War One battles combined .

The outbreak turned the previously strong, immune systems against them: 40% of the US navy were infected, while 36% of the army became ill.

Featured image: Emergency hospital during 1918 influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas ( National Museum of Health and Medicine )

You May Also Like

How a find in Scotland opens our eyes to an Iranian Empire

Do you know who built Petra?

The Dark History of Bearded Ladies

Did this Document Legitimise the Yorkists Claim to the Throne?

The Strange Sport of Pedestrianism Got Victorians Hooked on Coca

Puzzle Over These Ancient Greek Paradoxes

In Ancient Rome, Gladiators Rarely Fought to the Death

Archaeologists Uncover Two Roman Wells on a British Road

Young Stalin Made His Name as a Bank Robber

3 Things We Learned from Meet the Normans with Eleanor Janega

Reintroducing ‘Dan Snow’s History Hit’ Podcast with a Rebrand and Refresh

Don’t Try This Tudor Health Hack: Bathing in Distilled Puppy Juice

The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Why It Matters 100 Years Later

Here are 5 things you should know about the 1918 pandemic and why it matters 100 years later.

1. The 1918 Flu Virus Spread Quickly

In 1918, many people got very sick, very quickly. In March of that year, outbreaks of flu-like illness were first detected in the United States. More than 100 soldiers at Camp Funston in Fort Riley Kansas became ill with flu. Within a week, the number of flu cases quintupled. There were reports of some people dying within 24 hours or less. 1918 flu illness often progressed to organ failure and pneumonia, with pneumonia the cause of death for most of those who died. Young adults were hit hard. The average age of those who died during the pandemic was 28 years old.

2. No Prevention and No Treatment for the 1918 Pandemic Virus

3. Illness Overburdened the Health Care System

As the numbers of sick rose, the Red Cross put out desperate calls for trained nurses as well as untrained volunteers to help at emergency centers. In October of 1918, Congress approved a $1 million budget for the U. S. Public Health Service to recruit 1,000 medical doctors and more than 700 registered nurses.

At one point in Chicago, physicians were reporting a staggering number of new cases, reaching as high as 1,200 people each day. This in turn intensified the shortage of doctors and nurses. Additionally, hospitals in some areas were so overloaded with flu patients that schools, private homes and other buildings had to be converted into makeshift hospitals, some of which were staffed by medical students.

4. Major Advancements in Flu Prevention and Treatment since 1918

There is still much work to do to improve U.S. and global readiness for the next flu pandemic. More effective vaccines and antiviral drugs are needed in addition to better surveillance of influenza viruses in birds and pigs. CDC also is working to minimize the impact of future flu pandemics by supporting research that can enhance the use of community mitigation measures (i.e., temporarily closing schools, modifying, postponing, or canceling large public events, and creating physical distance between people in settings where they commonly come in contact with one another). These non-pharmaceutical interventions continue to be an integral component of efforts to control the spread of flu, and in the absence of flu vaccine, would be the first line of defense in a pandemic.

5. Risk of a Flu Pandemic is Ever-Present, but CDC is on the Frontlines Preparing to Protect Americans

CDC works tirelessly to protect Americans and the global community from the threat of a future flu pandemic. CDC works with domestic and global public health and animal health partners to monitor human and animal influenza viruses. This helps CDC know what viruses are spreading, where they are spreading, and what kind of illnesses they are causing. CDC also develops and distributes tests and materials to support influenza testing at state, local, territorial, and international laboratories so they can detect and characterize influenza viruses. In addition, CDC assists global and domestic experts in selecting candidate viruses to include in each year’s seasonal flu vaccine and guides prioritization of pandemic vaccine development. CDC routinely develops vaccine viruses used by manufacturers to make flu vaccines. CDC also supports state and local governments in preparing for the next flu pandemic, including planning and leading pandemic exercises across all levels of government. An effective response will diminish the potential for a repeat of the widespread devastation of the 1918 pandemic.

Visit CDC’s 1918 commemoration website for more information on the 1918 pandemic and CDC’s pandemic flu preparedness work.

63 comments on “The 1918 Flu Pandemic: Why It Matters 100 Years Later”

Comments listed below are posted by individuals not associated with CDC, unless otherwise stated. These comments do not represent the official views of CDC, and CDC does not guarantee that any information posted by individuals on this site is correct, and disclaims any liability for any loss or damage resulting from reliance on any such information. Read more about our comment policy » .

Hi, Thank you for this article. Very informative. Maybe the people that do not understand and do not accept the vaccination campaign will change their minds.

Excellent historical perspective on the 1918 incident. We have come a long way in treatment protocols and diagnostic advancements with respect to infectious diseases. The major concern,at this time, is an unknown pathogen which will be quickly spread worldwide my international jet travel. A few sick people on an aircraft entering the US could easy spread the disease from one end of the Country to the other. Depending on the conditions’ incubation period many more people will be affected before public health officials begin to see a problem. I guess the only thing we can be sure of is something similar will occur again , it’s just a matter of the right conditions and time.

This is a wonderful article on the influenza virus. I have extensively read about the pandemic, and its devastating effect on people. I must admit that I am appalled at the refusal to use trained nurses because they were Black Americans. That nonsense was part of the failure to help people in need of care at this crucial time . I must say it was hateful and ignorant of White Americans. White Americans are not reminded enough that they are immigrants to America just like any other race that came to this country from another country. America does not belong to white people. I don’t believe sick people care who is attending to them when they are on the brink of death.

Well done article. However. You could include a list of historical accounts for Further reading materials.

The possibility of another potential outbreak of any kind is a very scary and real test of how very little know. We indeed have come along way but still have a distance to go. .. Thank you for sharing this fascinating story.

Two of my grandparents were killed in their 30s by this epidemic, leaving my 1 year-old mother, my aunt, and my uncle orphaned. This is important stuff; people need to take influenza seriously.

My grandfather was a doctor in the Spokane Wa area and died from the flu in July of 1918 at age 46 . He was from the St Louis Missouri area and had been in the Spokane area for several years but could have visited or was visited by people from the St Louis area which is close to Kansas City to have caught the flu . Spokane was very isolated . This article gives no answer but gives some background to how he caught the flu in the middle of nowhere at the beginning of this pandemic

Would the mortality rate be as bad as the flu pandemic in 1918 where 675,000 people were killed? How would our economy be affected? Any thoughts?

The book “The Great Influenza” by John M. Barry has many historical references on this topic.

Good summary of the 1918 flu pandemic. But the sentence “The average age of those who died during the pandemic was 28 years old” (end of the first section) is inaccurate. Twenty-eight was the age at which mortality peaked among young adults, who were the hardest hit, along the very young and the very old. As for the average, variations in infant or old adult mortality could easily tip the balance away from 28 years.

In researching flu a few years ago, I read that one reason this flu killed people of supposedly optimum age for strength and resistance (~28 years), was for exactly that reason – their immune systems responded so quickly – with fluid in the lungs – that they drowned. People who responded more slowly, with less fluid produced less quickly – were more likely to survive.

By the way, if this thing posts (my first post ever on this site), I’m getting this message:

You are posting comments too quickly. Slow down.

(Please check your software)

I would agree with Tonya and Robert, there is an ever-present threat of a variant flu virus reeking havoc as many go unprepared for each flu season by not vaccinating, but also with a new, unknown pathogen. With the climate changing and the glacier ice melting to new low levels, bacteria, viruses and parasites previously encased in ice soon may be exposed to air, water, and humans. I am thankful for the diligent surveillance that the CDC and the WHO provides.

Thank you for that summary. The pandemic took my grandmother in the Spring of 1919. My father and his two sisters were orphans then. Their father had died in France, November 1918. It is always so sad for me to read about this.

Any plan to slow or stop a pandemic would include quickly identifying those who are contagious and minimizing their contact with others. However we do not have in place policies that would encourage that behavior, particularly in the low income and immigrant populations, including people who: * cannot afford to take time off work without pay * would lose their jobs if they did not show up * have no health insurance and can’t afford medical care * are afraid to seek care because of immigration status (their own or family member’s) And anyone who was quarantined would want to know that their basic needs would be met if they complied. I believe these issues would be best addressed in advance to overcome resistance. Once a potential pandemic starts, it will be difficult to get the necessary public and private buy-in, resources and authority until it is too late.

It’s surprising that to see that the first three items listed would apply to any similar pandemic of unknown origin today. Today’s air travel would spread an illness at previously unheard of rates. Couple that with an unknown origin and our health care systems would be over run just as they were in 1918.

Thank you so much for this article. I appreciate the information included and I pray that it convinces people with reservations to keep their own and their families health in mind for everyone’s sake but especially their own.

My grandmother was 11 years old in 1918. The family was from Philadelphia. I remember her telling me that she had to help load dead bodies into wagons. They would yell in the neighborhoods, “throw out your dead!” She never got the flu, but it must have been horrible! That is why we were always told never to spit on the streets. It can carry diseases, etc. People—Don’t think this cannot happen again. We live in an age where we can prevent the worst from happening when it comes to flu and other diseases. Get your flu shots!

Very educative write-up. A big lesson for us in Africa. The surveillance of influenza viruses must be sustained especially at animal-human interface to monitor possible new mutations. Thank you.

My grandfather was 15 years old. His parents and his two siblings were very ill with the flu so he ran to get help. By the time he got back to the house they were all dead. I am lying in bed with the H1N1 right now. Probably the sickest I’ve ever been. I personally believe facemasks should be mandatory and all public transportation. What a tragedy all the way around.

Great information on the flu pandemic. Very educative and sad.

History has taught us much about various past outbreaks. It’s the future unknown pathogens manmade or natural we need to worry about.

Great article on the flu pandemic. I have done a lot of studying on the issue. John Barry has written many books about the pandemic I find it incredible and riveting to learn about how people would wake up in the morning feeling fine and be dead in the evening. I have spoken to many people who experienced the flu through their families. I have always wondered if this can never happen again. Let’s hope not.

Great informative article thanks I`ve just been watching THE LATEST NEWS ON THE 2020 CORONAVIRUS! making me wonder ?? I also remember COLLAPSING as I was walking down the street with HONG KONG FLU in 1956 Woke up in hospital…..TOOK MANY WEEKS TO RECOVER!!

while air travel will spread the virus faster today than before, the news of such virus is traveling even faster today, as can be seen in the current outbreak of 2019CoV. People around the world are in a state of panic as soon as it is reported. China did a total lock down pretty quickly. Nowadays, we get more information about the characteristics of the virus, like the temperature and humidity condition that is favorable/unfavorable to it, Scientists can produce a vaccine much sooner than before. So yes, we should be vigilant, but we do not need to be too scared to live our life normally.

Reading this in 2020, and it looks like the U.S. has not learned much.

those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it.

Actually, if you read how fast the flu spread, and how many died, some within 24 hours, we have come a long way! It took over 30 years to develop a flu vaccine, and within 3 months of coronavirus hitting, we have already started the clinical trials of a vaccine. Amazing!!

It’s like you saw into the future. The very not so distant future. Thanks for writing this as it reinforces the steps and procedures being followed today. If only they had been implemented sooner.

Here we go all over again

From this article I think WHO and CDC have not learned much to be in preparation. After 100 year another virus is here to take million lives away. Poor nation like Africa is in trouble. America should have known better to be prepare after 100years. God save us all

Apparently, there was no national plan then either. The lack of leadership by politicians on national and local levels is appalling and the realization that many top officials refuse to accept and follow recommendations of the CDC and other experts is terrifying. We are following exactly the same recommendations as were suggested in 1918, and there is inconsistent use of the precautions that we know help. Please support those who are taking the Coronavirus seriously and working to help us all. Bless the CDC and Drs and nurses on the front lines trying to save us all.

Great information

Watching the overrun hospitals, lack of supplies and reliance on local and state authorities because the federal government cannot or will not help. Schools are canceled. All groups more than 10 people. Social distancing rules are in place. The economy is crashing. No possible vaccine. History is repeating itself. I am literally hiding in my home with my family, knowing it’s the only way to avoid it.

Thank you for this article. It certainly puts the current COVID-19 pandemic in perspective, as well as reinforcing the need for social distancing! We are fortunate to live in a time when significant advances have been made in medicine and technology.

The CDC dropped the ball on this one, we need to shut down the country to prevent a worst case scenario. (writing this on 3/30/20) The economy will tank no matter what, but we can prevent millions of deaths yet.

My mother’s cousin was 21 when the 1918 influenza epidemic hit. He had cerebral palsy and was at risk for disease and he died. It’s hard though to comprehend how the influenza reached his tiny town outside of Abilene, Texas. There was very little medicine for colds or pneumonia for anyone in that time period.

100 years later viruses are still a problem.

The history repeats itself, we can see USA as the richest country, powerful country, is so unprepared! Doctors and nurses are lacking of protective gears, yet they have to work with the patients who are infected with the virus! The States have to bid against one another for ventilators etc. So many people are infected and die from this neglected, unguided way ! So sad!

Very informative information and thanks to all those people that put this information together. It seems to be working for this coronavirus we are currently experiencing. Keep up the good work and lets try to do our best to improve what we have learned from this virus and make it better next time around as we can see …. there will be a next time …. just currently unknown as to when.

Sydney Daniels Looking back at the comments in 2018 it is haunting. The accuracy of concerns and predictions! The rapid spread through international travel , the less privileged forced to continue working ,not only to perish but spread it. The fear of an unknown pathogen and it’s economic impact. The parallels of past and present are too hard to ignore. The Spanish flu acting very similar to Coronavirus. There are several stories in the news of patients over 100, who were alive during the 1918 flu, surviving coronavirus. Is it a stretch to think whatever immunity they acquired back in 1918 could have given them an edge or are they just tough as nails!? Is it immunologically impossible being a different virus and the years past? Just a thought? Unfortunately the reassurance, given in this article, that we have multiple guardrails in place to prevent such a huge spread again was wishful thinking. God bless everyone and stay safe.

My grandfather died from the Spanish flu and struck both my father and uncle as children. My father suffered cardiomyopathy and succumbed to it decades later. Financial struggles where perhaps worse since women had less legal rights and job opportunities that had any semblance of equal pay. My grandmother supported her family through a variety of seamstress jobs and cleaning for those that could afford that luxury. History is a good teacher if we can learn from it.

Watching the BOSSA. 45 min documentary on the spanish flu of 1918 so enlightening also. The symptoms of severe cases were bizarre and freakish, fatal in less than 24 hrs. A second wave (fall 2020) of covid must be minimized if world wants to prevent millions of deaths. Unfortunately, so many spoiled americans are selfish and very impatient willing to risk and sacrifice many others lives for a day at the beach or a new tattoo. If only they all could have done a 6 month sentence in county jail they would see that they could stomach months of quarantine in their own homes standing on their head, provided ample food and necessities are avialable.Too bad history will be repeated and this will be a disaster for so many more that shall lose their lives

here we go again!

102 years later and the struggles that our ancestors dealt with daily are being resurfaced again. As an RN working in the frontlines with the current flu pandemic, the level of stress that is experienced among health care workers is almost unbearable. Just as the 1918 flu was fast to spread with no prevention or treatment plan in place, this new outbreak is fast to spread and hard to treat and prevent. Taking a lesson from the 1918 pandemic, our facility took to making the staff and the patients wear mask for all interactions during their stay at our facility in an effort to reduce the risk of spreading patient to nurse or nurse to patient. The most unnerving concern to me personally is the fact that unlike the 1918 flu, an estimated 50% of individuals who have the COVID-19 virus have experienced zero symptoms. This makes the task of identifying the positive patients from simple screening procedures much more difficult due to lack of testing ability to confirm actual positive patients. For example, we had an elderly man in our facility for more than two weeks for an unrelated health care issue, screening upon admission declared he was a zero risk for COVID-19 and he never exhibited a single symptom during his admission, however upon discharge and transfer to a rehab facility, he had a COVID-19 positive test result. He continues to have ZERO symptoms but has exposed multiple health care workers and family members to COVID-19. The risk of infecting health care workers who are already spread thin only increases the workload demand on those still able to work.

We are currently short staffed at our facility with most nurses working four to six 12 hour shifts per week to keep the work demand in our facility at a manageable level. With the re-opening of our surgical units and other outpatient services, the “extra” support we were receiving from their health care staff has diminished but the increased workload demand on the inpatient staff is ever growing as the community continues to open up and social distancing is not adhered to. Our COVID-19 related ER visits more than doubled over one weekend when beaches alone opened up. As with the 1918 pandemic, the call for help in many areas had been made even to the point of allowing current nursing students to perform duties as an RN.

Because health care facilities across our nation are short staffed and limited on PPE, the task of identifying positive flu patients is important to isolate the continued spread of the virus but to also protect the health care workers and reduce the waste of precious PPE. Just as our health care workers in the past, social distancing, hand washing and face covers are the best methods that we have available to help slow the spread of this virus.

A hard lesson learned in the 1918 pandemic was that the early shut down of large social events and gatherings could help slow the spread and decrease the the burden on the local healthcare facilities. The CDCs plans of closing down schools, shopping centers, social gatherings of large numbers, and bars/clubs was the outcome of that hard learned lesson from 1918. Our community seems to have fared well with the early closing as we have not had many local citizens hospitalized with COVID-19, we do have a many COVID-19 patients in our facilities due to hospital transfers however due to our location being near two other States, one of which is a well known hot zone. We are all in this together and just like our 1918 health care teams, we too have answered the call to aid our neighboring States.

Opening up the public with care and caution is going to have to occur as many small business owners have already had to close their doors to our community permanently due to the length of time they went with no income. The economical impact this virus had already had on our community is evident and will only be truly seen in the future as things begin to return to our “New” normal.

COVID19 will also last for years as compared to Spanish flu and we should take the precautionary measures seriously

That was hard to read , here we are again in 2020.

im postin just to post kepp up the good work guys

It was so good but it was only 100 years and we have a sickness that is killing the people.

My father and his younger sister both had the flu in Glasgow in 1919. He survived, his sister died. He never had the flu again, and I have never had it…I’m 81 now. I’ve been told I am immune and have never had the flu shot. There is an area south of Glasgow/northern England that has been studied because there is are a number of people there who are also immune. J. Wilson Saville

To keep this thread (article) in check and updated I’d like to add that there was hope of a slow down. However, the desire for normalcy has in turn resulted in a resurgence of the virus. Hospitals are now getting brunt of the aged ill. Some retirement homes are nearly at 75% plus positive to the virus, whereas; the nurses are infected as well and even though now overtaken by the virus are capable of working. In my opinion, this will continue for another year. I hope the timeframe is less, but the end result will likely be another depression. Our country needs to prepare and seek aid from other countries to prepare for this. The USA are the worlds leading consumers and I dint believe the rest of the world could take a financial hit like a US collapse.

Well, vaccines are on the way. Half of America is still crazy. I guess you could say we started “rounding the corner” on Nov. 3rd. Hopefully things back to normal this time next year.

Very good and informative article. Thank you

The Spanish fly and the COVID -19 are are bit similar

When roll out to massive vaccinate happens worldwide we will heal. It reminds me of the World War 2 armament. Once we got the ball rolling we were successful.

I was always strong never in the hospital because of illness. October 2020 came , and despite all my efforts to avoid COVID-19 I landed in the local hospital, and spent the month of October in the covid unit. The infectious disease specialists went to work with what was available, and saved my life. I was on oxygen until March, or April, and I was doing rehab at home until I could walk again. Thank God my wife and I were able to get our COVID-19 shots. Please get yours, everyone!!!

History have already repeating it self In a bad way and we did not learn anything at all ! .

The covid -19 or coronavirus in 2020

Life expectancy dropped by 12 years during the Spanish flu. The virus continued until 1957. Some believe a lack of nutrition played a part in the mortality rate at the time Life expectancy for COVID 19 is the same as normal life expectancy (around 78). Like the Spanish flu our body should adapt to the coming variations. Like the Spanish flu it may last decades.

Why was there a 37 year absence of flu pandemic between 1920 & 1957; yet subsequent to 1957 they have appeared more frequently?

@Sumeyo, I think you mean “The Spanish Flu” 😉

people did not learn about the requirements for this😑. I mean really!

Good info and everything but could had added more info

The article was worded very well and fairly informative. And that leads me to bring up a part of the Article that most people tend to over look. The flu started in the military and spread rapidly. When i was six years old i had very similar symptoms of the Spanish flue and I compared the symptoms of covid 19 and what I had when it was six was actually worse. Im 55 yrs old now and I haven’t had a flu shot in 36 years now and I have no intentions of getting another one with all the Chemical war fair going on in the world.

Post a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- What is the difference between influenza epidemics and influenza pandemics?

- What is pandemic influenza preparedness?

- What are the symptoms of influenza?

- What have been some of the world’s deadliest pandemics?

- How do pandemics end?

influenza pandemic of 1918–19

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Cleveland Clinic - Spanish Flu

- PNAS - Genesis and pathogenesis of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus

- New Zealand History Online - The 1918 influenza pandemic

- National Archives - The Flu Pandemic of 1918

- Ohio State University - Origins - The 1918 Flu Pandemic

- Live Science - 1918 influenza: The deadliest pandemic in history

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - 1918 Influenza: the Mother of All Pandemics

- Pan American Health Organization - Purple Death: The Great Flu of 1918

- Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage - The 1918 Spanish Flu

- influenza pandemic of 1918–19 - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

What was the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919?

The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 was the most severe influenza outbreak of the 20th century. The disease that caused this devastating pandemic has also been called the Spanish flu.

What caused the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919?

A virus called influenza type A subtype H1N1 is now known to have been the cause of the extreme mortality of the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919.

Which countries were affected by the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919?

Outbreaks of the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 occurred in nearly every inhabited part of the world. Although it remains uncertain where the virus first emerged, it quickly spread through western Europe and around the world—first in ports, then from city to city along main transportation routes.

How many people died as a result of the influenza pandemic of 1918–1919?

The influenza pandemic of 1918–1919 resulted in an estimated 25 million deaths, though some researchers have projected that it caused as many as 40–50 million deaths.

influenza pandemic of 1918–19 , the most severe influenza outbreak of the 20th century and, in terms of total numbers of deaths, among the most devastating pandemics in human history.

- Read more about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic .

Influenza is caused by a virus that is transmitted from person to person through airborne respiratory secretions. An outbreak can occur if a new strain of influenza virus emerges against which the population has no immunity. The influenza pandemic of 1918–19 resulted from such an occurrence and affected populations throughout the world. An influenza virus called influenza type A subtype H1N1 is now known to have been the cause of the extreme mortality of this pandemic, which resulted in an estimated 25 million deaths, though some researchers have projected that it caused as many as 40–50 million deaths.

The pandemic occurred in three waves. The first apparently originated in early March 1918, during World War I . Although it remains uncertain where the virus first emerged, it quickly spread through western Europe, and by July it had spread to Poland. The first wave of influenza was comparatively mild. However, during the summer a more lethal type of disease was recognized, and this form fully emerged in August 1918. Pneumonia often developed quickly, with death usually coming two days after the first indications of the flu. For example, at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, U.S., six days after the first case of influenza was reported, there were 6,674 cases. The third wave of the pandemic occurred in the following winter, and by the spring the virus had run its course. In the two later waves about half the deaths were among 20- to 40-year-olds, an unusual mortality age pattern for influenza.

Outbreaks of the flu occurred in nearly every inhabited part of the world, first in ports, then spreading from city to city along the main transportation routes. India is believed to have suffered at least 12.5 million deaths during the pandemic, and the disease reached distant islands in the South Pacific, including New Zealand and Samoa . In the United States about 550,000 people died. Most deaths worldwide occurred during the brutal second and third waves. Other outbreaks of Spanish influenza occurred in the 1920s but with declining virulence.

The Spanish flu: The global impact of the largest influenza pandemic in history

Parts of the article were revised in May 2023, and the chart on death tolls from flu pandemics was updated in April 2024.

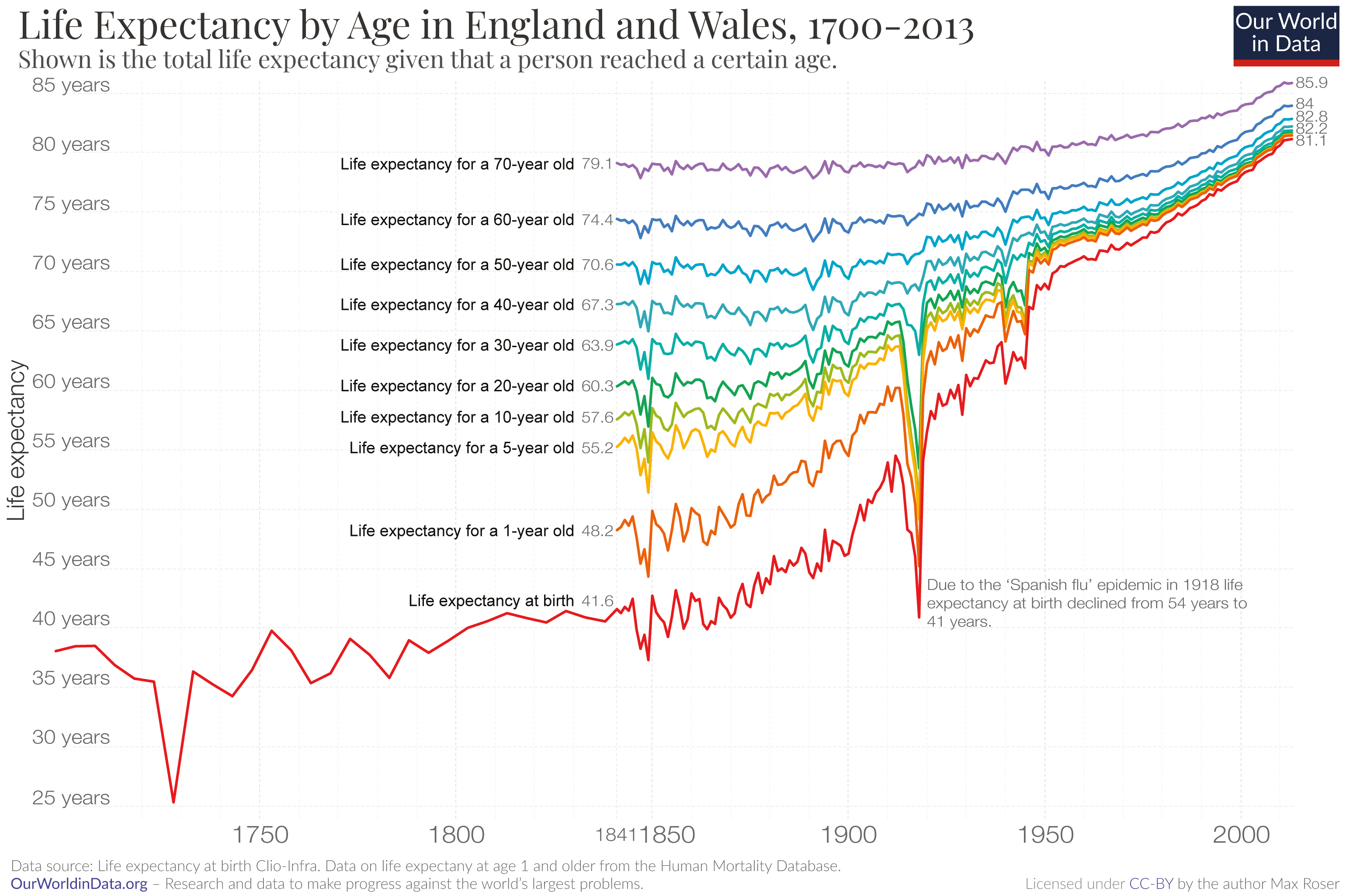

In the last 150 years the world has seen an unprecedented improvement in health. The visualization shows that in many countries life expectancy, which measures the average age of death, doubled from around 40 years or less to more than 80 years. This was not just an achievement across the countries shown here; life expectancy has doubled in all regions of the world.

What also stands out is how abrupt and damning negative health events can be. Most striking is the large, sudden decline of life expectancy in 1918, caused by an unusually deadly influenza pandemic that became known as the ‘Spanish flu’.

To make sense of the fact life expectancy declined so abruptly, one has to keep in mind what it measures. Period life expectancy , which is the precise name for this measure, captures the mortality in one particular year . It summarizes the mortality in a particular year by calculating the average age of death of a hypothetical cohort of people for which that year’s mortality pattern would remain constant throughout their entire lifetimes.

This influenza outbreak wasn’t restricted to Spain and it didn’t even originate there. Recent genetic research suggests that the strain emerged a few years earlier, around 1915, but did not take off until later on. The earliest recorded outbreak was in Kansas in the United States in 1918. 1

But it was named as such because Spain was neutral in the First World War (1914-18), which meant it was free to report on the severity of the pandemic, while countries that were fighting tried to suppress reports on how the influenza impacted their population to maintain morale and not appear weakened in the eyes of the enemies. Since it is very valuable to speak openly about the threat of an infectious disease I think Spain should be proud that it was not like other countries at that time.

The virus spread rapidly and eventually reached all parts of the world: the epidemic became a pandemic. 2 Even in a much less-connected world the virus eventually reached extremely remote places such as the Alaskan wilderness and Samoa in the middle of the Pacific islands. In these remote places the mortality rate was often particularly high. 3

How many people died in the Spanish flu pandemic?

The global death count of the flu today:.

To have a context for the severity of influenza pandemics it might be helpful to know the death count of a typical flu season. Current estimates for the annual number of deaths from influenza are around 400,000 deaths per year. Paget et al (2019) suggest an average of 389,000 with an uncertainty range 294,000 from 518,000. 4 This means that in recent years the flu was responsible for the death of 0.005% of the world population. 5 Even in comparison to the low estimate for the death count of the Spanish flu (17.4 million) this pandemic, more than a century ago, caused a death rate that was 182-times higher than today’s baseline.

Global deaths of the Spanish flu

Several research teams have worked on the difficult problem of reconstructing the global health impact of the Spanish flu.

The visualization here shows the available estimates from the different research publications discussed in the following. The range of published estimates for the Spanish flu is particularly wide.

The widely cited study by Johnson and Mueller (2002) arrives at a very high estimate of at least 50 million global deaths. But the authors suggest that this could be an underestimation and that the true death toll was as high as 100 million. 6

Patterson and Pyle (1991) estimated that between 24.7 and 39.3 million died from the pandemic. 7

The more recent study by Spreeuwenberg et al. (2018) concluded that earlier estimates have been too high. Their own estimate is 17.4 million deaths. 8

The global death rate of the Spanish flu

How do these estimates compare with the size of the world population at the time? How large was the share who died in the pandemic?

Estimates suggest that the world population in 1918 was 1.8 billion.

Based on this, the low estimate of 17.4 million deaths by Spreeuwenberg et al. (2018) implies that the Spanish flu killed almost 1% of the world population. 9

The estimate of 50 million deaths published by Johnson and Mueller implies that the Spanish flu killed 2.7% of the world population. And if it was in fact higher – 100 million as these authors suggest – then the global death rate would have been 5.4%. 10

The world population was growing by around 13 million every year in this period which suggests that the period of the Spanish flu was likely the last time in history when the world population was declining. 11

Other large influenza pandemics

The Spanish flu pandemic was the largest, but not the only large recent influenza pandemic.

Two decades before the Spanish flu the Russian flu pandemic (1889-1894) is believed to have killed 1 million people. 12

Estimates for the death toll of the “Asian Flu” (1957-1958) range from 1.7 to 2.7 million according to Spreeuwenberg et al. (2018). 13

The same authors estimate that the “Hong Kong Flu” (1968-1969) killed between 2 and 3.8 million people. 13

The “Russian Flu” pandemic of 1889-1890 is believed to be caused by an H3 pandemic virus. 14 According to Spreeuwenberg et al. (2018) around 3.7 to 5.1 million people died worldwide. 13

The “Swine flu” pandemic of 2009-2010 was caused by a new H1N1 pandemic virus. Several research groups have made estimates of the global death toll, which ranges from 130,000 to 1.87 million people worldwide. 15

What becomes clear from this overview are two things: influenza pandemics are not rare, but the Spanish flu of 1918 was by far the most devastating influenza pandemic in recorded history.

The impact of the Spanish flu on different age groups

This last visualization here shows the life expectancy in England and Wales by age.

The red line shows the life expectancy for a newborn, with the rainbow-colored lines above showing how long a person could expect to live once they had reached that given, older, age. The light green line, for example, represents the life expectancy for children who have reached age 10.

It shows that life expectancy increased at all ages, which means that the often-heard assertion that life expectancy ‘only’ increased because child mortality declined is not true .

With respect to the impact of the Spanish flu it is striking that the visualization shows that the pandemic had little impact on older people. While the life expectancy at birth and at young ages declined by more than ten years, the life expectancy of 60- and 70-year olds saw no change. This is at odds with what one would reasonably expect: older populations tend to be most vulnerable to influenza outbreaks and respiratory infections. If we look at mortality for both lower respiratory infections (pneumonia) and upper respiratory infections today, death rates are highest for those who are 70 years and older.

This data tells us that young people accounted for a large share of the deaths, this made this pandemic especially devastating.

Why were older people so resilient to the 1918 pandemic? The research literature suggests that this was the case because older people had lived through an earlier flu outbreak – the already discussed ‘Russian flu pandemic’ of 1889–90 – which gave those who lived through it some immunity for the later outbreak of the Spanish flu. 16

The earlier 1889-90 pandemic might have given the older population some immunity, but was a destructive event in itself. According to Smith 132,000 people died in England, Wales, and Ireland alone. 17

How the Spanish flu differs from the Coronavirus outbreak in 2020

Writing in early March 2020 it is an obvious question to ask how the ongoing outbreak of Covid-19 compares. There are a number of important differences that should be considered.

They are not the same disease and the virus causing these diseases are very different. The virus that causes Covid-19 is a coronavirus, not an influenza virus that caused the Spanish flu and the other influenza pandemics listed above.

The age-specific mortality seems to be very different. As we’ve seen above, the Spanish flu in 1918 was especially dangerous to infants and younger people. The new coronavirus that causes Covid-19 appears to be most lethal to the elderly, based on early evidence in China. 18

We’ve also seen above that during the Spanish flu many countries tried to suppress any information about the influenza outbreak. Today the sharing of data, research, and news is certainly not perfect, but very different and much more open than in the past.

But it is true that the world today is much better connected. In 1918 it was railroads and steamships that connected the world. Today planes can carry people and viruses to many corners of the world in a very short time.

Differences in health systems and infrastructure also matter. The Spanish flu hit the world in the days before antibiotics were invented; and many deaths, perhaps most, were not caused by the influenza virus itself, but by secondary bacterial infections. Morens et al (2008) found that during the Spanish flu “the majority of deaths … likely resulted directly from secondary bacterial pneumonia caused by common upper respiratory–tract bacteria.” 19

And not just health systems were different, but also the health and living conditions of the global population. The 1918 flu hit a world population of which a very large share was extremely poor – large shares of the population were undernourished, in most parts of the world the populations lived in very poor health , and overcrowding, poor sanitation and low hygiene standards were common. Additionally the populations in many parts of the world were weakened by a global war. Public resources were small and many countries had just spent large shares of their resources on the war.

While most of the world is much richer and healthier now , the concern today too is that it is the poorest people that are going to be hit hardest by the Covid-19 outbreak. 20

These differences suggest that one should be cautious in drawing lessons from the outbreak a century ago.

But the Spanish flu reminds us just how large the impact of a pandemic can be, even in countries that had already been successful in improving population health. A new pathogen can cause terrible devastation and lead to the death of millions. For this reason the Spanish flu has been cited as a warning and as a motivation to prepare well for large pandemic outbreaks, which have been considered likely by many researchers. 21

Worobey, M., Han, G.-Z., & Rambaut, A. (2014). Genesis and pathogenesis of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza A virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(22), 8107–8112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1324197111

Barry, J. M. (2004). The site of origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic and its public health implications. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-2-3

For the definitions of epidemic and pandemic see the CDC here .

Burnet F. M., Clark E. (1942) – Influenza: A Survey of the Last 50 Years in the Light of Modern Work on the Virus of Epidemic Influenza. London: Macmillan. Partly online on Google books.

The mortality rate in some populations like Alaska and Samoa were said to be 90% and 25% respectively. See the following two publications:

McLane, J. R. (2013). Paradise locked: The 1918 influenza pandemic in American Samoa. Sites: a journal of social anthropology and cultural studies , 10(2), 30-51.

Mamelund, S. E. (2017). Profiling a Pandemic. Who were the victims of the Spanish flu?{ref} While peak mortality was reached in 1918 the pandemic did not wane until two years later in late 1920.

Paget et al (2019) suggest an “average of 389 000 (uncertainty range 294 000-518 000) respiratory deaths were associated with influenza globally each year”.

John Paget, Peter Spreeuwenberg, Vivek Charu Robert J Taylor, A Danielle Iuliano, Joseph Bresee, Lone Simonsen, Cecile Viboud,3 and for the Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator Network and GLaMOR Collaborating Teams (2019) – Global mortality associated with seasonal influenza epidemics: New burden estimates and predictors from the GLaMOR Project. In J Glob Health. 2019 Dec; 9(2): 020421. Published online 2019 Oct 22. doi: 10.7189/jogh.09.020421 PMCID: PMC6815659 PMID: 31673337 Online here .

This is (389,000/7,500,000,000)*100=0.0052%

From the paper: Further research has seen the consistent upward revision of the estimated global mortality of the pandemic, which a 1920s calculation put in the vicinity of 21.5 million. A 1991 paper revised the mortality as being in the range 24.7-39.3 million. This paper suggests that it was of the order of 50 million. However, it must be acknowledged that even this vast figure may be substantially lower than the real toll, perhaps as much as 100 percent understated.

Johnson, N.P. and Mueller, J. (2002) – Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish" influenza pandemic. In Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 76(1), pp.105-115. Online here .

The paper includes detailed breakdowns of mortality estimates by world region and country.

Patterson and Pyle (1991) wrote 'we believe that approximately 30 million is the best estimate for the terrible demographic toll of the influenza pandemic of 1918' and published a range from 24.7-39.3 million deaths.

Patterson, K.D. and Pyle, G.F. (1991) – The geography and mortality of the 1918 influenza pandemic. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 65(1), p.4. Online here .

P. Spreeuwenberg; et al. (1 December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12): 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMID 30202996. Online here .

The calculation is (17,400,000/1,832,196,157)*100=0.95

50,000,000 deaths / 1,832,196,157 people = 0.02729 And with a death count twice is high: 0.05458.

In available historical reconstructions (like this one ) this decline is not shown. The reason for this is that precise annual counts of the world population are not available for the past.

Instead historians try to reconstruct the population figures for 5-year or 10-year intervals and the annual estimates are interpolations between these estimates.

In other words, if we had precise annual counts they would likely show a decline of the world population in 1918.

Nickol, M.E., Kindrachuk, J. (2019) – A year of terror and a century of reflection: perspectives on the great influenza pandemic of 1918–1919. BMC Infect Dis 19, 117 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-3750-8

According to Smith (1995) 132,000 died in England, Wales, and Ireland alone.

Smith F. B. (1995) – The Russian influenza in the United Kingdom, 1889-1894. Soc. Hist. Med. 8 55–73. Online here .

Spreeuwenberg, P., Kroneman, M., & Paget, J. (2018). Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. American Journal of Epidemiology, 187(12), 2561–2567. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy191

Dawood, F. S., Iuliano, A. D., Reed, C., Meltzer, M. I., Shay, D. K., Cheng, P.-Y., Bandaranayake, D., Breiman, R. F., Brooks, W. A., Buchy, P., Feikin, D. R., Fowler, K. B., Gordon, A., Hien, N. T., Horby, P., Huang, Q. S., Katz, M. A., Krishnan, A., Lal, R., … Widdowson, M.-A. (2012). Estimated global mortality associated with the first 12 months of 2009 pandemic influenza A H1N1 virus circulation: A modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 12(9), 687–695. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70121-4

Simonsen, L., Spreeuwenberg, P., Lustig, R., Taylor, R. J., Fleming, D. M., Kroneman, M., Van Kerkhove, M. D., Mounts, A. W., Paget, W. J., & the GLaMOR Collaborating Teams. (2013). Global Mortality Estimates for the 2009 Influenza Pandemic from the GLaMOR Project: A Modeling Study. PLoS Medicine, 10(11), e1001558. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001558

Gagnon et al. (2013) – Age-Specific Mortality During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Unravelling the Mystery of High Young Adult Mortality.PLoS One. 2013; 8(8): e69586. Published online 2013 Aug 5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069586. Online here .

The Russian flu pandemic was a devastating event in itself. Smith (1995) estimates that the Russian flu killed 132,000 in England, Wales, and Ireland.

Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi (2020) – The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Feb 17;41(2):145-151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. Online here .

Morens D. M., Taubenberger J. K., Fauci A. S. (2008) – Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 198 962–970. 10.1086/591708. Online here .

Gilbert, Marius, Giulia Pullano, Francesco Pinotti, Eugenio Valdano, Chiara Poletto, Pierre-Yves Boëlle, Eric D’Ortenzio, et al. (2020) – “Preparedness and Vulnerability of African Countries against Importations of COVID-19: A Modelling Study.” The Lancet (February 20, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30411-6 .

Alyssa S. Parpia, Martial L. Ndeffo-Mbah, Natasha S. Wenzel, and Alison P. Galvani (2016) – Effects of Response to 2014–2015 Ebola Outbreak on Deaths from Malaria, HIV/AIDS, and Tuberculosis, West Africa. In Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Mar; 22(3): 433–441. doi: 10.3201/eid2203.150977 PMCID: PMC4766886 PMID: 26886846 Online here .

See for example: Pandemic influenza preparedness and response – WHO guidance document. Published in 2009 by the WHO. Online here .Roman Duda (2016) – Problem profile: Biorisk reduction. Published by 80,000 hours. Online here .

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

As the 1918 Flu Emerged, Cover‑Up and Denial Helped It Spread

By: Becky Little

Updated: October 4, 2023 | Original: May 26, 2020

“ Spanish flu ” has been used to describe the flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 and the name suggests the outbreak started in Spain. But the term is actually a misnomer and points to a key fact: nations involved in World War I didn’t accurately report their flu outbreaks.

Spain remained neutral throughout World War I and its press freely reported its flu cases, including when the Spanish king Alfonso XIII contracted it in the spring of 1918. This led to the misperception that the flu had originated or was at its worst in Spain.

“Basically, it gets called the ‘Spanish flu’ because the Spanish media did their job,” says Lora Vogt , curator of education at the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. In Great Britain and the United States—which has a long history of blaming other countries for disease —the outbreak was also known as the “Spanish grip” or “Spanish Lady.”

Historians aren’t actually sure where the 1918 flu strain began, but the first recorded cases were at a U.S. Army camp in Kansas in March 1918. By the end of 1919, it had infected up to a third of the world’s population and killed some 50 million people. It was the worst flu pandemic in recorded history, and it was likely exacerbated by a combination of censorship, skepticism and denial among warring nations.

“The viruses don’t care where they come from, they just love taking advantage of wartime censorship,” says Carol R. Byerly, author of Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I . “Censorship is very dangerous during a pandemic.”

The Flu in Europe

When the flu broke out in 1918, wartime press censorship was more entrenched in European countries because Europe had been fighting since 1914 , while the United States had only entered the war in 1917 . It’s hard to know the scope of this censorship, since the most effective way to cover something up is to not leave publicly-accessible records of its suppression. Discovering the impact of censorship is also complicated by the fact that when governments pass censorship laws, people often censor themselves out of fear of breaking the law.

In Great Britain, which fought for the Allied Powers, “the Defense of the Realm Act was used to a certain extent to suppress…news stories that might be a threat to national morale,” says Catharine Arnold , author of Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History . “The government can slam what’s called a D-Notice on [a news story]—‘D’ for Defense—and it means it can’t be published because it’s not in the national interest.”

Both newspapers and public officials claimed during the flu’s first wave in the spring and early summer of 1918 that it wasn’t a serious threat. The Illustrated London News wrote that the 1918 flu was “so mild as to show that the original virus is becoming attenuated by frequent transmission.” Sir Arthur Newsholme, chief medical officer of the British Local Government Board, suggested it was unpatriotic to be concerned with the flu rather than the war, Arnold says.

The flu’s second wave, which began in late summer and worsened that fall, was far deadlier . Even so, warring nations continued to try to hide it. In August, the interior minister of Italy—another Allied Power— denied reports of the flu’s spread. In September, British officials and newspaper barons suppressed news that the prime minister had caught the flu while on a morale-boosting trip to Manchester. Instead, the Manchester Guardian explained his extended stay in the city by claiming he’d caught a “severe chill” in a rainstorm.

Warring nations covered up the flu to protect morale among their own citizens and soldiers, but also because they didn’t want enemy nations to know they were suffering an outbreak. The flu devastated General Erich Ludendorff’s German troops so badly that he had to put off his last offensive. The general, whose empire fought for the Central Powers, was anxious to hide his troops’ flu outbreaks from the opposing Allied Powers.

“Ludendorff is famous for observing [flu outbreaks among soldiers] and saying, oh my god this is the end of the war,” Byerly says. “His soldiers are getting influenza and he doesn’t want anybody to know, because then the French could attack him.”

The Pandemic in the United States

The United States entered WWI as an Allied Power in April 1917. A little over a year later, it passed the 1918 Sedition Act , which made it a crime to say anything the government perceived as harming the country or the war effort. Again, it’s difficult to know the extent to which the government may have used this to silence reports of the flu, or the extent to which newspapers self-censored for fear of retribution. Whatever the motivation, some U.S. newspapers downplayed the risk of the flu or the extent of its spread.

In anticipation of Philadelphia’s “Liberty Loan March” in September, doctors tried to use the press to warn citizens that it was unsafe. Yet city newspaper editors refused to run articles or print doctors’ letters about their concerns. In addition to trying to warn the public through the press, doctors had also unsuccessfully tried to convince Philadelphia’s public health director to cancel the march.

The war bonds fundraiser drew several thousand people, creating the perfect place for the virus to spread. Over the next four weeks, the flu killed 12,191 people in Philadelphia.

How U.S. Cities Tried to Halt the Spread of the 1918 Spanish Flu

How U.S. city officials responded to the 1918 pandemic played a critical role in how many residents lived—and died.

More People Died in the 1918 Flu Pandemic Than in WWI

See the heroes of the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic in color.

Why the Second Wave of the 1918 Flu Pandemic Was So Deadly

The first strain of the 1918 flu wasn’t particularly deadly. Then it came back in the fall with a vengeance.

Similarly, many U.S. military and government officials downplayed the flu or declined to implement health measures that would help slow its spread. Byerly says the Army’s medical department recognized the threat the flu posed to the troops and urged officials to stop troop transports, halt the draft and quarantine soldiers; but they faced resistance from the line command, the War Department and President Woodrow Wilson .

Wilson’s administration eventually responded to their pleas by suspending one draft and reducing the occupancy on troop ships by 15 percent, but other than that it didn’t take the extensive measures medical workers recommended. General Peyton March successfully convinced Wilson that the U.S. should not stop the transports, and as a result, soldiers continued to get sick. By the end of the year, about 45,000 U.S. Army soldiers had died from the flu.

The pandemic was so devastating among WWI nations that some historians have suggested the flu hastened the end of the war. The nations declared armistice on November 11 amid the pandemic’s worst wave.

In April 1919, the flu even disrupted the Paris Peace Conference when President Wilson came down with a debilitating case. As when the British prime minister had contracted the flu back in September, Wilson’s administration hid the news from the public. His personal doctor instead told the press the president had caught a cold from the Paris rain.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Social and Economic Impacts of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic

India lost 16.7 million people. Five hundred and fifty thousand died in the US. Spain’s death rate was low, but the disease was called “Spanish flu” because the press there was first to report it.

A n estimated 40 million people, or 2.1 percent of the global population, died in the Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918–20. If a similar pandemic occurred today, it would result in 150 million deaths worldwide. In The Coronavirus and the Great Influenza Pandemic: Lessons from the “Spanish Flu” for the Coronavirus’s Potential Effects on Mortality and Economic Activity (NBER Working Paper 26866 ), Robert J. Barro , José F. Ursúa , and Joanna Weng study the cross-country differences in the death rate associated with the virus outbreak, and the associated impacts on economic activity.

The flu spread in three waves: the first in the spring of 1918, the second and most deadly from September 1918 to January 1919, and the third from February 1919 through the end of the year. The first two waves were intensified by the final years of World War I; the authors work to distinguish the effect of the flu on the death rate from the effect of the war. The flu was particularly deadly for young adults without pre-existing conditions, which increased its economic impact relative to a disease that mostly affects the very young and the very old.

The researchers analyze mortality data from more than 40 countries, accounting for 92 percent of the world’s population in 1918 and an even larger share of its GDP. The mortality rate varied from 0.3 percent in Australia, which imposed a quarantine in 1918, to 5.8 percent in Kenya and 5.2 percent in India, which lost 16.7 million people over the three years of the pandemic. The flu killed 550,000 in the United States, or 0.5 percent of the population. In Spain, 300,000 died for a death rate of 1.4 percent, around average. There is no consensus as to where the flu originated; it became associated with Spain because the press there was first to report it.

There is little reliable data on how many people were infected by the virus. The most common estimate, one third of the population, is based on a 1919 study of 11 US cities; it may not be representative of the US population, let alone the global population.

The researchers estimate that in the typical country, the pandemic reduced real per capita GDP by 6 percent and private consumption by 8 percent, declines comparable to those seen in the Great Recession of 2008–2009. In the United States, the flu’s toll was much lower: a 1.5 percent decline in GDP and a 2.1 percent drop in consumption.

The decline in economic activity combined with elevated inflation resulted in large declines in the real returns on stocks and short-term government bonds. For example, countries experiencing the average death rate of 2 percent saw real stock returns drop by 26 percentage points. The estimated drop in the United States was much smaller, 7 percentage points.

The researchers note that “the probability that COVID-19 reaches anything close to the Great Influenza Pandemic seems remote, given advances in public health care and measures that are being taken to mitigate propagation.” They note, however, that some of the mitigation efforts that are currently underway, particularly those affecting commerce and travel, are likely to amplify the virus’s impact on economic activity.

In a related study, Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions and Mortality in US Cities during the Great Influenza Pandemic, 1918–19 (NBER Working Paper 27049 ), Robert Barro analyzes data on the mitigation policies pursued by US cities as they confronted the flu epidemic. There were substantial cross-sectional differences in the policies that were adopted. Relative to the average number of flu deaths per week over the course of the epidemic, the number of flu deaths at the peak was lower in cities that pursued more aggressive policies, such as school closing and prohibition of public gatherings. However, the estimated effect of these policies on the total number of deaths was modest and statistically indistinguishable from zero. One potential explanation of this finding is that the interventions had a mean duration of only around one month.

— Steve Maas

Researchers

NBER periodicals and newsletters may be reproduced freely with appropriate attribution.

More from NBER