164 Case Studies: Real Stories Of People Overcoming Struggles of Mental Health

At Tracking Happiness, we’re dedicated to helping others around the world overcome struggles of mental health.

In 2022, we published a survey of 5,521 respondents and found:

- 88% of our respondents experienced mental health issues in the past year.

- 25% of people don’t feel comfortable sharing their struggles with anyone, not even their closest friends.

In order to break the stigma that surrounds mental health struggles, we’re looking to share your stories.

Overcoming struggles

They say that everyone you meet is engaged in a great struggle. No matter how well someone manages to hide it, there’s always something to overcome, a struggle to deal with, an obstacle to climb.

And when someone is engaged in a struggle, that person is looking for others to join him. Because we, as human beings, don’t thrive when we feel alone in facing a struggle.

Let’s throw rocks together

Overcoming your struggles is like defeating an angry giant. You try to throw rocks at it, but how much damage is one little rock gonna do?

Tracking Happiness can become your partner in facing this giant. We are on a mission to share all your stories of overcoming mental health struggles. By doing so, we want to help inspire you to overcome the things that you’re struggling with, while also breaking the stigma of mental health.

Which explains the phrase: “Let’s throw rocks together”.

Let’s throw rocks together, and become better at overcoming our struggles collectively. If you’re interested in becoming a part of this and sharing your story, click this link!

Case studies

August 13, 2024

Finding Happiness At Sea As A Yacht Captain After Overcoming Depression and Anxiety

“If a situation is making you unhappy – a marriage, a job, a family member – anything – change the situation. You can leave, you can stop speaking to someone (yes, even a parent or another family member), and you can do so free of guilt because you are in charge of your own happiness, and life is too short to choose anything different for yourself.”

Struggled with: Anxiety Depression Suicidal

Helped by: Medication Therapy

August 6, 2024

Overcoming Neglect, Childhood Trauma and Abuse Through Careful Self-Improvement

“When I was 12 years old, my parents moved into their own place, along with my brother and sister. They left me with my grandparents. I could only see my family on weekends, and on Sunday evenings I would go back home. I was not able to build a normal relationship with my brother and sister. I even thought at one point that I was adopted, which was against all logic.”

Struggled with: Abuse Childhood

Helped by: Journaling Self-improvement

July 30, 2024

Overcoming a Rare Autoimmune Disease With a Careful Diet and Self-Improvement

“There were weeks when I wouldn’t leave my house, feeling too overwhelmed and exhausted to face the world. I tend to isolate myself rather than reaching out to others, which only compounded my feelings of loneliness and despair. I had to repattern my behavior and learn to ask for help or talk about my feelings, but it wasn’t easy. I internalized a lot of my pain and frustration, which made me feel even more isolated.”

Struggled with: Anxiety Autoimmune disease

Helped by: Self-improvement

July 23, 2024

Surviving The Boston Marathon Bombings While Facing TBI and Medical Gaslighting

“As I literally lived on his couch, with my port-a-potty in his living room, my partner eventually applied for permanent disability status for me. But, even the doctor gaslighted me, told me I was physically able to work, and reported the same to the government. In reality, I was so dizzy with vertigo, this same doctor refused to let me walk to and from our car, by myself, fearing I’d fall and sue!”

Struggled with: CPTSD Traumatic Brain Injury

Helped by: Treatment

July 16, 2024

Somatic Therapy Helped Me Heal From CPTSD After Years of Childhood Abuse

“At 22 years old, I knew that I was dying of alcoholism. I accepted that. The trauma symptoms I experienced were too overwhelming to stop drinking. When I was sober, I would sometimes experience 30 to 40 body memories of being sexually assaulted–again and again in succession. I drank to feel numb.”

Struggled with: Abuse Addiction CPTSD Suicidal

Helped by: Social support Therapy

July 9, 2024

Learning To Live With Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Therapy And A Positive Mindset

“Raising four young children and battling a chronic illness with no cure was challenging for me. On the outside, I looked OK. But I wasn’t and in some ways today still have flare-ups and struggles, the difference is, I now know how to maintain it, especially knowing this will be the rest of my life regardless!”

Struggled with: Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Helped by: Therapy Treatment

July 4, 2024

How A Rescue Dog Helped Me Overcome TBI, Depression and Suicidal Ideation

“I sat on the summer-hot pavement, and no one stopped or asked me if I was okay. No one called the police. People walked around me as quickly as possible. When I was all cried out, I walked home to my empty house. I bought a set of knives, ostensibly for cooking, but that was not the reason. I had thought about pills, and every day I researched how many of each prescription drug I was on would I need to take to die. Using a sharp knife seemed so much easier.”

Struggled with: Depression Suicidal Traumatic Brain Injury

Helped by: Medication Pets Volunteering

July 2, 2024

Walking El Camino de Santiago Helped Me Reconnect With My Authentic Self

“Beneath the outward bravado, I battled with self-doubt and kept wondering why genuine connections seemed beyond my ability. Even though I put out valiant efforts to conceal it, my inner turmoil seeped out, leaving me feeling exposed and vulnerable. And, I knew they could tell.”

Struggled with: Feeling lost People-pleasing Self-doubt

Helped by: Self-acceptance Self-awareness

June 27, 2024

My Journey of Overcoming Heartbreak Thanks to Self-Care and The Support Of Friends

“I’ve learned that finding the right people to confide in, those who offer genuine support and empathy, can make a significant difference in navigating these challenges. It takes time and trust to build those connections, but they are invaluable.”

Struggled with: Breakup

Helped by: Self-Care Social support

June 19, 2024

How Therapy, Self-Help and Medication Help Me Live With Depression and Anxiety

“When the next depressive episode hit in 2018, I was devastated. How could this happen again when I thought I had it all figured out? I experienced some of the darkest moments of my life and a nearly complete loss of hope.”

Struggled with: Anxiety Bipolar Disorder Depression Suicidal

Mental Health Case Study: Understanding Depression through a Real-life Example

Through the lens of a gripping real-life case study, we delve into the depths of depression, unraveling its complexities and shedding light on the power of understanding mental health through individual experiences. Mental health case studies serve as invaluable tools in our quest to comprehend the intricate workings of the human mind and the various conditions that can affect it. By examining real-life examples, we gain profound insights into the lived experiences of individuals grappling with mental health challenges, allowing us to develop more effective strategies for diagnosis, treatment, and support.

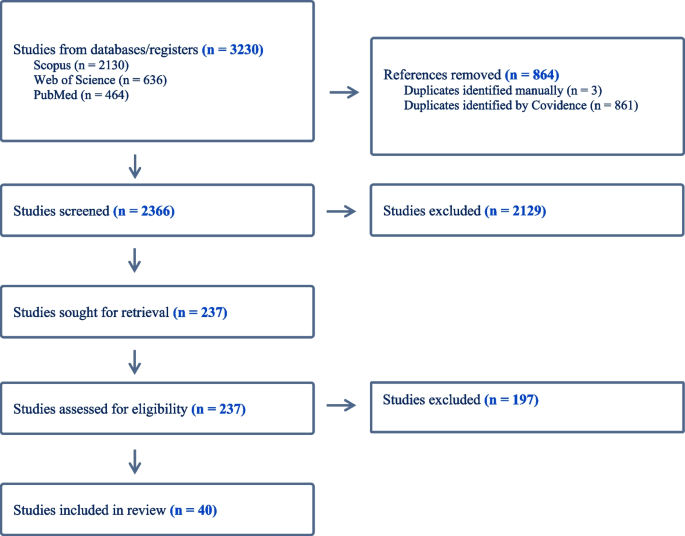

The Importance of Case Studies in Understanding Mental Health

Case studies play a crucial role in the field of mental health research and practice. They provide a unique window into the personal narratives of individuals facing mental health challenges, offering a level of detail and context that is often missing from broader statistical analyses. By focusing on specific cases, researchers and clinicians can gain a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to mental health conditions.

One of the primary benefits of using real-life examples in mental health case studies is the ability to humanize the experience of mental illness. These narratives help to break down stigma and misconceptions surrounding mental health conditions, fostering empathy and understanding among both professionals and the general public. By sharing the stories of individuals who have faced and overcome mental health challenges, case studies can also provide hope and inspiration to those currently struggling with similar issues.

Depression, in particular, is a common mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide. Disability Function Report Example Answers for Depression and Bipolar: A Comprehensive Guide offers valuable insights into how depression can impact daily functioning and the importance of accurate reporting in disability assessments. By examining depression through the lens of a case study, we can gain a more nuanced understanding of its manifestations, challenges, and potential treatment approaches.

Understanding Depression

Before delving into our case study, it’s essential to establish a clear understanding of depression and its impact on individuals and society. Depression is a complex mental health disorder characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of interest in activities. It can affect a person’s thoughts, emotions, behaviors, and overall well-being.

Some common symptoms of depression include:

– Persistent sad, anxious, or “empty” mood – Feelings of hopelessness or pessimism – Irritability – Loss of interest or pleasure in hobbies and activities – Decreased energy or fatigue – Difficulty concentrating, remembering, or making decisions – Sleep disturbances (insomnia or oversleeping) – Appetite and weight changes – Physical aches or pains without clear physical causes – Thoughts of death or suicide

The prevalence of depression worldwide is staggering. According to the World Health Organization, more than 264 million people of all ages suffer from depression globally. It is a leading cause of disability and contributes significantly to the overall global burden of disease. The impact of depression extends far beyond the individual, affecting families, communities, and economies.

Depression can have profound consequences on an individual’s quality of life, relationships, and ability to function in daily activities. It can lead to decreased productivity at work or school, strained personal relationships, and increased risk of other health problems. The economic burden of depression is also substantial, with costs associated with healthcare, lost productivity, and disability.

The Significance of Case Studies in Mental Health Research

Case studies serve as powerful tools in mental health research, offering unique insights that complement broader statistical analyses and controlled experiments. They allow researchers and clinicians to explore the nuances of individual experiences, providing a rich tapestry of information that can inform our understanding of mental health conditions and guide the development of more effective treatment strategies.

One of the key advantages of case studies is their ability to capture the complexity of mental health conditions. Unlike standardized questionnaires or diagnostic criteria, case studies can reveal the intricate interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors that contribute to an individual’s mental health. This holistic approach is particularly valuable in understanding conditions like depression, which often have multifaceted causes and manifestations.

Case studies also play a crucial role in the development of treatment strategies. By examining the detailed accounts of individuals who have undergone various interventions, researchers and clinicians can identify patterns of effectiveness and potential barriers to treatment. This information can then be used to refine existing approaches or develop new, more targeted interventions.

Moreover, case studies contribute to the advancement of mental health research by generating hypotheses and identifying areas for further investigation. They can highlight unique aspects of a condition or treatment that may not be apparent in larger-scale studies, prompting researchers to explore new avenues of inquiry.

Examining a Real-life Case Study of Depression

To illustrate the power of case studies in understanding depression, let’s examine the story of Sarah, a 32-year-old marketing executive who sought help for persistent feelings of sadness and loss of interest in her once-beloved activities. Sarah’s case provides a compelling example of how depression can manifest in high-functioning individuals and the challenges they face in seeking and receiving appropriate treatment.

Background: Sarah had always been an ambitious and driven individual, excelling in her career and maintaining an active social life. However, over the past year, she began to experience a gradual decline in her mood and energy levels. Initially, she attributed these changes to work stress and the demands of her busy lifestyle. As time went on, Sarah found herself increasingly isolated, withdrawing from friends and family, and struggling to find joy in activities she once loved.

Presentation of Symptoms: When Sarah finally sought help from a mental health professional, she presented with the following symptoms:

– Persistent feelings of sadness and emptiness – Loss of interest in hobbies and social activities – Difficulty concentrating at work – Insomnia and daytime fatigue – Unexplained physical aches and pains – Feelings of worthlessness and guilt – Occasional thoughts of death, though no active suicidal ideation

Initial Diagnosis: Based on Sarah’s symptoms and their duration, her therapist diagnosed her with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). This diagnosis was supported by the presence of multiple core symptoms of depression that had persisted for more than two weeks and significantly impacted her daily functioning.

The Treatment Journey

Sarah’s case study provides an opportunity to explore the various treatment options available for depression and examine their effectiveness in a real-world context. Supporting a Caseworker’s Client Who Struggles with Depression offers valuable insights into the role of support systems in managing depression, which can complement professional treatment approaches.

Overview of Treatment Options: There are several evidence-based treatments available for depression, including:

1. Psychotherapy: Various forms of talk therapy, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), can help individuals identify and change negative thought patterns and behaviors associated with depression.

2. Medication: Antidepressants, such as Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs), can help regulate brain chemistry and alleviate symptoms of depression.

3. Combination Therapy: Many individuals benefit from a combination of psychotherapy and medication.

4. Lifestyle Changes: Exercise, improved sleep habits, and stress reduction techniques can complement other treatments.

5. Alternative Therapies: Some individuals find relief through approaches like mindfulness meditation, acupuncture, or light therapy.

Treatment Plan for Sarah: After careful consideration of Sarah’s symptoms, preferences, and lifestyle, her treatment team developed a comprehensive plan that included:

1. Weekly Cognitive Behavioral Therapy sessions to address negative thought patterns and develop coping strategies.

2. Prescription of an SSRI antidepressant to help alleviate her symptoms.

3. Recommendations for lifestyle changes, including regular exercise and improved sleep hygiene.

4. Gradual reintroduction of social activities and hobbies to combat isolation.

Effectiveness of the Treatment Approach: Sarah’s response to treatment was monitored closely over the following months. Initially, she experienced some side effects from the medication, including mild nausea and headaches, which subsided after a few weeks. As she continued with therapy and medication, Sarah began to notice gradual improvements in her mood and energy levels.

The CBT sessions proved particularly helpful in challenging Sarah’s negative self-perceptions and developing more balanced thinking patterns. She learned to recognize and reframe her automatic negative thoughts, which had been contributing to her feelings of worthlessness and guilt.

The combination of medication and therapy allowed Sarah to regain the motivation to engage in physical exercise and social activities. As she reintegrated these positive habits into her life, she experienced further improvements in her mood and overall well-being.

The Outcome and Lessons Learned

Sarah’s journey through depression and treatment offers valuable insights into the complexities of mental health and the effectiveness of various interventions. Understanding the Link Between Sapolsky and Depression provides additional context on the biological underpinnings of depression, which can complement the insights gained from individual case studies.

Progress and Challenges: Over the course of six months, Sarah made significant progress in managing her depression. Her mood stabilized, and she regained interest in her work and social life. She reported feeling more energetic and optimistic about the future. However, her journey was not without challenges. Sarah experienced setbacks during particularly stressful periods at work and struggled with the stigma associated with taking medication for mental health.

One of the most significant challenges Sarah faced was learning to prioritize her mental health in a high-pressure work environment. She had to develop new boundaries and communication strategies to manage her workload effectively without compromising her well-being.

Key Lessons Learned: Sarah’s case study highlights several important lessons about depression and its treatment:

1. Early intervention is crucial: Sarah’s initial reluctance to seek help led to a prolongation of her symptoms. Recognizing and addressing mental health concerns early can prevent the condition from worsening.

2. Treatment is often multifaceted: The combination of medication, therapy, and lifestyle changes proved most effective for Sarah, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive treatment approach.

3. Recovery is a process: Sarah’s improvement was gradual and non-linear, with setbacks along the way. This emphasizes the need for patience and persistence in mental health treatment.

4. Social support is vital: Reintegrating social activities and maintaining connections with friends and family played a crucial role in Sarah’s recovery.

5. Workplace mental health awareness is essential: Sarah’s experience highlights the need for greater understanding and support for mental health issues in professional settings.

6. Stigma remains a significant barrier: Despite her progress, Sarah struggled with feelings of shame and fear of judgment related to her depression diagnosis and treatment.

Sarah’s case study provides a vivid illustration of the complexities of depression and the power of comprehensive, individualized treatment approaches. By examining her journey, we gain valuable insights into the lived experience of depression, the challenges of seeking and maintaining treatment, and the potential for recovery.

The significance of case studies in understanding and treating mental health conditions cannot be overstated. They offer a level of detail and nuance that complements broader research methodologies, providing clinicians and researchers with invaluable insights into the diverse manifestations of mental health disorders and the effectiveness of various interventions.

As we continue to explore mental health through case studies, it’s important to recognize the diversity of experiences within conditions like depression. Personal Bipolar Psychosis Stories: Understanding Bipolar Disorder Through Real Experiences offers insights into another complex mental health condition, illustrating the range of experiences individuals may face.

Furthermore, it’s crucial to consider how mental health issues are portrayed in popular culture, as these representations can shape public perceptions. Understanding Mental Disorders in Winnie the Pooh: Exploring the Depiction of Depression provides an interesting perspective on how mental health themes can be embedded in seemingly lighthearted stories.

The field of mental health research and treatment continues to evolve, driven by the insights gained from individual experiences and comprehensive studies. By combining the rich, detailed narratives provided by case studies with broader research methodologies, we can develop more effective, personalized approaches to mental health care. As we move forward, it is essential to continue exploring and sharing these stories, fostering greater understanding, empathy, and support for those facing mental health challenges.

References:

1. World Health Organization. (2021). Depression. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression

2. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

3. Beck, A. T., & Alford, B. A. (2009). Depression: Causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press.

4. Cuijpers, P., Quero, S., Dowrick, C., & Arroll, B. (2019). Psychological treatment of depression in primary care: Recent developments. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(12), 129.

5. Malhi, G. S., & Mann, J. J. (2018). Depression. The Lancet, 392(10161), 2299-2312.

6. Otte, C., Gold, S. M., Penninx, B. W., Pariante, C. M., Etkin, A., Fava, M., … & Schatzberg, A. F. (2016). Major depressive disorder. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2(1), 1-20.

7. Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping. Holt paperbacks.

8. Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage publications.

Similar Posts

Semaglutide and Depression: Understanding the Connection

As scientists unravel the complex interplay between weight-loss medications and mental health, a surprising connection between Semaglutide and depression has emerged, sparking both concern and curiosity in the medical community. This revelation has prompted researchers and healthcare professionals to delve deeper into the potential implications of this relationship, seeking to understand the mechanisms at play…

Is Depression Selfish? Understanding the Relationship Between Mental Health and Selfishness

Shattering the misconception that depression equates to selfishness, we delve into the intricate relationship between mental health and self-preservation, challenging societal stigmas along the way. Depression is a complex mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide, yet it remains widely misunderstood and stigmatized. One of the most damaging misconceptions is the idea that…

Understanding Self-Loathing: Is it a Sign of Depression?

Self-loathing is a complex emotional state that can significantly impact an individual’s mental health and overall well-being. It’s a feeling that often goes hand in hand with depression, creating a challenging cycle that can be difficult to break. In this article, we’ll explore the intricate relationship between self-loathing and depression, examining their signs, symptoms, and…

Understanding Reciprocal Changes in ECG: A Comprehensive Guide to Horizontal ST Depression

Electrocardiography (ECG) is a fundamental diagnostic tool in cardiology, providing crucial insights into the heart’s electrical activity. Among the various patterns and changes observed in ECG readings, reciprocal changes play a significant role in identifying and understanding cardiac events. This comprehensive guide delves into the intricacies of reciprocal changes in ECG, with a particular focus…

Understanding Obdurate Depression: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment Options

Locked in an unyielding grip, obdurate depression challenges millions worldwide, defying conventional treatments and leaving sufferers desperately searching for a glimmer of hope. This persistent and treatment-resistant form of depression can be a formidable adversary, often leaving individuals feeling trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of despair. However, understanding the nature of obdurate depression, its…

Understanding the Link Between COVID-19, Depression, and Anxiety

As the world grappled with an invisible enemy, a silent epidemic of depression and anxiety surged alongside COVID-19, intertwining physical and mental health in unprecedented ways. The global pandemic not only threatened our physical well-being but also took a significant toll on our mental health, creating a complex web of challenges that affected millions of…

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Mental health case studies

Driving up quality in mental health care.

Mental health care across the NHS in England is changing to improve the experiences of the people who use them. In many areas, a transformation is already under way, offering people better and earlier access as well as more personalised care, whilst building partnerships which reach beyond the NHS to create integrated and innovative approaches to mental health care and support.

Find out more through our case studies and films about how mental health care across the NHS is changing and developing to better meet people’s needs.

- Children and young people (CYP)

- Community mental health

- Crisis mental health

- Early intervention in psychosis (EIP)

- Improving access to psychological therapies (IAPT)

- Perinatal mental health

- Severe mental illness (SMI)

- Staff mental health and wellbeing

- Other mental health case studies

- Archived mental health case studies

Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

- Theresa Cerulli, MD

- Tina Matthews-Hayes, DNP, FNP, PMHNP

Custom Around the Practice Video Series

Experts in psychiatry review the case of a 27-year-old woman who presents for evaluation of a complex depressive disorder.

EP: 1 . Patient Case #1: 27-Year-Old Woman With Bipolar Disorder

Ep: 2 . clinical significance of bipolar disorder, ep: 3 . clinical impressions from patient case #1, ep: 4 . diagnosis of bipolar disorder, ep: 5 . treatment options for bipolar disorder, ep: 6 . patient case #2: 47-year-old man with treatment resistant depression (trd), ep: 7 . patient case #2 continued: novel second-generation antipsychotics, ep: 8 . role of telemedicine in bipolar disorder.

Michael E. Thase, MD : Hello and welcome to this Psychiatric Times™ Around the Practice , “Identification and Management of Bipolar Disorder. ”I’m Michael Thase, professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Joining me today are: Dr Gustavo Alva, the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California; Dr Theresa Cerulli, the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in North Andover, Massachusetts; and Dr Tina Matthew-Hayes, a dual-certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

Today we are going to highlight challenges with identifying bipolar disorder, discuss strategies for optimizing treatment, comment on telehealth utilization, and walk through 2 interesting patient cases. We’ll also involve our audience by using several polling questions, and these results will be shared after the program.

Without further ado, welcome and let’s begin. Here’s our first polling question. What percentage of your patients with bipolar disorder have 1 or more co-occurring psychiatric condition? a. 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. 50%-70%, or e. more than 70%.

Now, here’s our second polling question. What percentage of your referred patients with bipolar disorder were initially misdiagnosed? Would you say a. less than 10%, b. 10%-30%, c. 30%-50%, d. more than 50%, up to 70%, or e. greater than 70%.

We’re going to go ahead to patient case No. 1. This is a 27-year-old woman who’s presented for evaluation of a complex depressive syndrome. She has not benefitted from 2 recent trials of antidepressants—sertraline and escitalopram. This is her third lifetime depressive episode. It began back in the fall, and she described the episode as occurring right “out of the blue.” Further discussion revealed, however, that she had talked with several confidantes about her problems and that she realized she had been disappointed and frustrated for being passed over unfairly for a promotion at work. She had also been saddened by the unusually early death of her favorite aunt.

Now, our patient has a past history of ADHD [attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder], which was recognized when she was in middle school and for which she took methylphenidate for adolescence and much of her young adult life. As she was wrapping up with college, she decided that this medication sometimes disrupted her sleep and gave her an irritable edge, and decided that she might be better off not taking it. Her medical history was unremarkable. She is taking escitalopram at the time of our initial evaluation, and the dose was just reduced by her PCP [primary care physician]from 20 mg to 10 mg because she subjectively thought the medicine might actually be making her worse.

On the day of her first visit, we get a PHQ-9 [9-item Patient Health Questionnaire]. The score is 16, which is in the moderate depression range. She filled out the MDQ [Mood Disorder Questionnaire] and scored a whopping 10, which is not the highest possible score but it is higher than 95% of people who take this inventory.

At the time of our interview, our patient tells us that her No. 1 symptom is her low mood and her ease to tears. In fact, she was tearful during the interview. She also reports that her normal trouble concentrating, attributable to the ADHD, is actually substantially worse. Additionally, in contrast to her usual diet, she has a tendency to overeat and may have gained as much as 5 kg over the last 4 months. She reports an irregular sleep cycle and tends to have periods of hypersomnolence, especially on the weekends, and then days on end where she might sleep only 4 hours a night despite feeling tired.

Upon examination, her mood is positively reactive, and by that I mean she can lift her spirits in conversation, show some preserved sense of humor, and does not appear as severely depressed as she subjectively describes. Furthermore, she would say that in contrast to other times in her life when she’s been depressed, that she’s actually had no loss of libido, and in fact her libido might even be somewhat increased. Over the last month or so, she’s had several uncharacteristic casual hook-ups.

So the differential diagnosis for this patient included major depressive disorder, recurrent unipolar with mixed features, versus bipolar II disorder, with an antecedent history of ADHD. I think the high MDQ score and recurrent threshold level of mixed symptoms within a diagnosable depressive episode certainly increase the chances that this patient’s illness should be thought of on the bipolar spectrum. Of course, this formulation is strengthened by the fact that she has an early age of onset of recurrent depression, that her current episode, despite having mixed features, has reverse vegetative features as well. We also have the observation that antidepressant therapy has seemed to make her condition worse, not better.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Dr. Thase is a professor of psychiatry at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Dr. Alva is the medical director of ATP Clinical Research in Costa Mesa, California.

Dr. Cerulli is the medical director of Cerulli and Associates in Andover, Massachusetts.

Dr. Tina Matthew-Hayes is a dual certified nurse practitioner at Western PA Behavioral Health Resources in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania.

Evaluating the Efficacy of Lumateperone for MDD and Bipolar Depression With Mixed Features

Blue Light, Depression, and Bipolar Disorder

Efficacy of Modafinil for Treatment of Neurocognitive Impairment in Bipolar Disorder

Four Myths About Lamotrigine

Securing the Future of Lithium Research

An Update on Early Intervention in Psychotic Disorders

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Children's mental health case studies

- Parenting and caregiving

- Mental health

Explore the experiences of children and families with these interdisciplinary case studies. Designed to help professionals and students explore the strengths and needs of children and their families, each case presents a detailed situation, related research, problem-solving questions and feedback for the user. Use these cases on your own or in classes and training events

Each case study:

- Explores the experiences of a child and family over time.

- Introduces theories, research and practice ideas about children's mental health.

- Shows the needs of a child at specific stages of development.

- Invites users to “try on the hat” of different specific professionals.

By completing a case study participants will:

- Examine the needs of children from an interdisciplinary perspective.

- Recognize the importance of prevention/early intervention in children’s mental health.

- Apply ecological and developmental perspectives to children’s mental health.

- Predict probable outcomes for children based on services they receive.

Case studies prompt users to practice making decisions that are:

- Research-based.

- Practice-based.

- Best to meet a child and family's needs in that moment.

Children’s mental health service delivery systems often face significant challenges.

- Services can be disconnected and hard to access.

- Stigma can prevent people from seeking help.

- Parents, teachers and other direct providers can become overwhelmed with piecing together a system of care that meets the needs of an individual child.

- Professionals can be unaware of the theories and perspectives under which others serving the same family work

- Professionals may face challenges doing interdisciplinary work.

- Limited funding promotes competition between organizations trying to serve families.

These case studies help explore life-like mental health situations and decision-making. Case studies introduce characters with history, relationships and real-life problems. They offer users the opportunity to:

- Examine all these details, as well as pertinent research.

- Make informed decisions about intervention based on the available information.

The case study also allows users to see how preventive decisions can change outcomes later on. At every step, the case content and learning format encourages users to review the research to inform their decisions.

Each case study emphasizes the need to consider a growing child within ecological, developmental, and interdisciplinary frameworks.

- Ecological approaches consider all the levels of influence on a child.

- Developmental approaches recognize that children are constantly growing and developing. They may learn some things before other things.

- Interdisciplinary perspectives recognize that the needs of children will not be met within the perspectives and theories of a single discipline.

There are currently two different case students available. Each case study reflects a set of themes that the child and family experience.

The About Steven case study addresses:

- Adolescent depression.

- School mental health.

- Rural mental health services.

- Social/emotional development.

The Brianna and Tanya case study reflects themes of:

- Infant and early childhood mental health.

- Educational disparities.

- Trauma and toxic stress.

- Financial insecurity.

- Intergenerational issues.

The case studies are designed with many audiences in mind:

Practitioners from a variety of fields. This includes social work, education, nursing, public health, mental health, and others.

Professionals in training, including those attending graduate or undergraduate classes.

The broader community.

Each case is based on the research, theories, practices and perspectives of people in all these areas. The case studies emphasize the importance of considering an interdisciplinary framework. Children’s needs cannot be met within the perspective of a single discipline.

The complex problems children face need solutions that integrate many and diverse ways of knowing. The case studies also help everyone better understand the mental health needs of children. We all have a role to play.

These case has been piloted within:

Graduate and undergraduate courses.

Discipline-specific and interdisciplinary settings.

Professional organizations.

Currently, the case studies are being offered to instructors and their staff and students in graduate and undergraduate level courses. They are designed to supplement existing course curricula.

Instructors have used the case study effectively by:

- Assigning the entire case at one time as homework. This is followed by in-class discussion or a reflective writing assignment relevant to a course.

- Assigning sections of the case throughout the course. Instructors then require students to prepare for in-class discussion pertinent to that section.

- Creating writing, research or presentation assignments based on specific sections of course content.

- Focusing on a specific theme present in the case that is pertinent to the course. Instructors use this as a launching point for deeper study.

- Constructing other in-class creative experiences with the case.

- Collaborating with other instructors to hold interdisciplinary discussions about the case.

To get started with a particular case, visit the related web page and follow the instructions to register. Once you register as an instructor, you will receive information for your co-instructors, teaching assistants and students. Get more information on the following web pages.

- Brianna and Tanya: A case study about infant and early childhood mental health

- About Steven: A children’s mental health case study about depression

Cari Michaels, Extension educator

Reviewed in 2023

© 2024 Regents of the University of Minnesota. All rights reserved. The University of Minnesota is an equal opportunity educator and employer.

- Report Web Disability-Related Issue |

- Privacy Statement |

- Staff intranet

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part 2 Lucy’s Story

2.4 Lucy case study 3: Mental illness diagnosis

Nicole Graham

Introduction to case study

Lucy has experienced the symptoms of mental illness during her lifespan; however, it was not until her early twenties that she was formally diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder. In the case study below, we explore the symptomology that Lucy experienced in the lead up to and post diagnosis. Lucy needs to consider her mental illness in relation to her work as a Registered Nurse and as she continues to move through the various stages of adulthood.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this case study, you should be able to:

- Identify and consider the symptoms of mental illness.

- Develop an understanding of contributing biopsychosocial stressors that may exacerbate the symptoms of mental illness as experienced by Lucy.

- Critically analyse the professional, ethical, and legal requirements and considerations for a registered health professional living with chronic illness.

Lucy’s small group of friends describe her as energetic and ‘a party person’. Although she sometimes disappears from her social group for periods of time, her friends are not aware that Lucy experiences periods of intense depression. At times Lucy cannot find the energy to get out of bed or even get dressed, sometimes for extended periods. As she gets older, these feelings and moods, as she describes them, get more intense. She loves feeling high on life. This is when she has an abundance of energy, is not worried about what people think of her and often does not need to sleep. These are the times when she feels she can achieve her goals. One of these times is when she decides to become a nurse. She excels at university, loves the intensity of study, practice and the party lifestyle. Emergency Nursing is her calling. The fast pace, the quick turnaround matches her endless energy. The fact that she struggles to stay focused for extended periods of time is something she needs to consider in her nursing career, to ensure it does not impact negatively on her care.

Unfortunately, Lucy has experienced challenges in her career. For example, her manager often comments on her mental illness after she had openly disclosed her diagnosis. It is challenging for her to hear her colleagues speak badly about a person who presents with mental illness. The stigma she hears directed at others challenges her. She is also very aware that it could be her presenting to the Emergency Department when she is unwell and in need of further support. Lucy is constantly worried that her colleagues will read her medical chart and think she is unsafe to practice.

While the symptoms that cause significant distress and disruption to her life began in her late teens, they intensified after she commenced antidepressant medication after the loss of her child. She subsequently ceased taking them due to side effects. These medications particularly impact on her ability to be creative and reduce her libido and energy. By the time she turns 18, she notices more frequent, intense mood swings, often accompanied by intense feelings of anxiety. During her high periods, Lucy enjoys the energy, the feeling of euphoria, the increased desire to exercise, her engagement with people, and being impulsive and creative. Lucas appreciates her increased libido. However, during these periods of high mood, Lucy also has impaired boundaries and is often flirtatious in her behaviour towards both friends and people she doesn’t know. She also increases her spending and has limited sleep. Lucas is often frustrated by this behaviour, leading to fights. On occasion Lucas slaps her and gets into fights with the people she is flirting with. These periods can last days and sometimes weeks, always followed by depressive episodes.

When she is in the low phases of her mood, Lucy experiences an overwhelming sense of hopelessness and emptiness. She is unable to find the energy to get out of bed, shower or take interest in simple daily activities. Lucas gets frustrated and dismisses Lucy’s statements of wanting to end her life as ‘attention seeking’. Lucy often expresses the desire to leave this world when she feels this way. When Lucas seeks support from the local general practitioner, nothing really gets resolved. The GP prescribes the medication; Lucy regains her desire to participate in life; then stops the medication due to side effects which extend to gastrointestinal upsets, on top of the decrease in libido and not feeling like herself. When Lucy is referred to a psychologist, she does not engage for more than one session, saying that she doesn’t like the person and feels they judge her lifestyle. When the psychologist attempts to explore a family history of mental illness, Lucy says no- one in her family has it and dismisses the concept.

The intense ups and downs are briefly interrupted with periods of lower intensity. During these times, Lucy feels worried about various aspects of her life and finds it challenging to let go of her anxious thoughts. There are times when Lucy has symptoms like racing heart, gastrointestinal update and shortness of breath. She spends a great deal of time wanting her life to be better. Her desire to move on from Lucas and to start a new life becomes more intense. Lucy is confident this is not a symptom of depression; it is just that she is unhappy in her relationship. Lucy starts to consider career options, feeling that not working affects her lifestyle, freedom and health. As she explores different options on the internet, Lucy comes across a chat room. Using the chat name ‘Foxy Lady 20’, she develops new friendships. She finds herself talking a lot with a man named Lincoln who lives on the Gold Coast.

After a brief but intense period talking with Lincoln online, Lucy abruptly decides to leave Lucas and her life in Bundaberg to move in with Lincoln. Lincoln, aged 26, 5 years older than Lucy, owns a modest home on the Gold Coast and has stable employment at the local casino. Their relationship progresses quickly and within a month Lincoln has proposed to Lucy. They plan to marry within 12 months.

Lucy is now happy with her life and feels stable. She decides to pursue a degree in nursing at the local university. Lucy enrols and makes many new friends, enjoying the intensity of study and a new social scene. Her fiancé Lincoln also enjoys the social aspects of their relationship. During university examination periods, Lucy experiences strong emotions. At the suggestion of an academic she respects, she makes an appointment with the university counselling service. After the first 3 appointments, Lucy self-discovers, with the support of her counsellor, that she might benefit from a specialist consultation with a psychiatrist. She comes to recognise that her symptoms are not within the normal range experienced by her peers. Lincoln is incredibly supportive and attends the appointments with Lucy, extending on the information she provides. Lucy reveals information about her grandmother, who was considered eccentric, and known for her periods of elevated mood and manic behaviour. The treating psychiatrist suggests Lucy may be living with bipolar affective disorder and encourages her to trial the medication lithium.

Lucy does not enjoy the side effects of decreased energy, nausea and feeling dazed and ceases taking the lithium during the university break period. This causes Lucy to again experience an intense elevation of her mood, accompanied by risk-taking behaviours. Lucy goes out frequently, nightclubbing and being flirtatious with her friends. She becomes aggressive towards a woman who confronts Lucy about her behaviour with her boyfriend in the nightclub. This is the first time Lucy exhibits this type of response, along with very pressured speech, pacing and an inability to calm herself. The police are called. They recommend Lucy gets assessed at the hospital after hearing from Lincoln that she has ceased her medication. Lucy is admitted for a brief period in the acute mental health ward. After stabilising and recommencing lithium, Lucy returns to the care of her psychiatrist in the community. The discharge notes report that Lucy had been previously diagnosed with bipolar disorder, may also be experiencing anxiety related symptoms, and have personality vulnerabilities.

Lucy is in the final year of her university studies when she has a professional experience placement in the emergency ward. Lucy really enjoys the fast pace, as well as the variety of complex presentations. Lucy feels it matches her energy and her desire for frequent change. After she completes her studies, Lucy applies and is successful in obtaining a position at the local hospital. Throughout her initial graduate year, Lucy balances life with a diagnosis of mental illness as well as a program of her own self-care. She finds the roster patterns in particular incredibly challenging and again becomes unwell. She goes through a period of depression and is unable to work. During this period, Lucy experiences an overwhelming sense of hopelessness and considers ending her life. Again, she requires a higher level of engagement from her treating team. Lucy agrees she is not fit to work during this time and has a period of leave without pay to recover. She has disclosed to her manager that she has been diagnosed with a mental illness and later discusses how shift work impacts her sleep and her overall mental wellbeing.

Over time, Lucy develops strategies to maintain wellness. However, she describes her relationship with the Nursing Unit Manager as strained, due to her inability to work night shift as her medical certificate shows. Lucy says she is often reminded of the impact that her set roster has on her colleagues. Lucy also feels unheard and dismissed when she raises workplace concerns, as her manager attributes her feelings to her mental health deteriorating. Lucy has a further period when her mental health deteriorates. However, this time it is due to a change in her medication.

As Lucy and Lincoln have a desire to have a child, Lucy was advised that she cease lithium in favour of lamotrigine, to reduce the risk of harm to the baby. Lucy ceases work during the period when her mental health deteriorates during the initial phase of changing medication. Lucy recommences lithium after she ceases breastfeeding their son at 4 months, with good effect and returns to work.

Case study questions

- Consider the symptoms that Lucy experiences and indicate whether they align with the suggested diagnosis.

- Identify the biopsychosocial contributing factors that could impact mental health and wellness.

- Review and identify the professional disclosure requirements of a Registered Nurse who lives with mental illness in your local area.

- Identify self-care strategies that Lucy or yourself as a health professional could implement to support mental health and wellbeing.

Thinking point

Sometimes people do not agree with a diagnosis of mental illness, which can be incorrectly labelled as ‘denial’ by health professionals. It is possible that the person is unable to perceive or be aware of their illness. This inability of insight is termed anosognosia (Amador, 2023). The cause of anosognosia in simple terms can be due to a non-functioning or impaired part of the frontal lobe of the brain, which may be caused by schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other diseases such as dementia (Kirsch et al., 2021).

As healthcare workers will likely care for someone who is experiencing anosognosia, it is important to reflect on how you may work with someone who does not have the level of insight you would have hoped. Below is a roleplay activity whereby you can experience what it might be like to communicate with someone experiencing anosognosia. Reflect on your communication skills and identify strategies you could use to improve your therapeutic engagement.

Role play activity – Caring for a person who is experiencing anosognosia

Learning objectives.

- Demonstrate therapeutic engagement with someone who is experiencing mental illness

- Identify effective communication skills

- Reflect on challenges and identify professional learning needs

Resources required

- Suitable location to act out scene.

- One additional person to play the role of service user.

Two people assume role of either service user or clinician. If time permits, switch roles and repeat.

- Lucy has been commenced on lithium carbonate ER for treatment of her bipolar disorder.

- Lucy is attending the health care facility every week, as per the treating psychiatrist’s requests.

- The clinician’s role is to monitor whether Lucy is experiencing any side effects.

Role 1 – Clinician

- Clinician assumes role of health care worker in a health care setting of choice.

- Lucy has presented and your role is to ask Lucy whether she is experiencing any side effects and whether she has noticed any improvements in her mental state.

Role 2 – Lucy who lives with bipolar

- Lucy responds that she does not understand the need for the tablets. She also denies having a mental illness. Lucy says she will do what she is told, but does not think there is anything wrong with her. Lucy thinks she is just an energetic person who at times gets sad, which she describes as ‘perfectly normal.’ Lucy is not experiencing any negative side effects, but says she would like clarification about why the doctor has prescribed this medication.

Post role play debrief

Reflect and discuss your experiences, both as Lucy and as the clinician. Identify and discuss what was effective and what were the challenges.

Identify professional development opportunities and develop a learning plan to achieve your goals.

Additional resources that might be helpful

- Australian Prescriber: Lithium therapy and its interactions

- LEAP Institute: The impact of anosognosia and noncompliance (video)

Key information and links to other resources

Fisher (2022) suggests there are large numbers of health professionals who live with mental illness and recognise the practice value that comes with lived experience. However, the author also notes that as stigma is rife within the health care environment, disclosing mental illness can trigger an enhanced surveillance of the health professional’s practice or impede professional relationships (Fisher, 2022).

It is evident that the case studies derived from Lucy’s life story are complex and holistic care is essential. The biopsychosocial model was first conceptualised in 1977 by George Engel, who suggests it is not only a person’s medical condition, but also psychological and social factors that influence health and wellbeing (Engel,2012).

Below are examples of what you as a health professional could consider in each domain.

- Biological: Age, gender, physical health conditions, drug effects, genetic vulnerabilities

- Psychological: Emotions, thoughts, behaviours, coping skills, values

- Social: Living situation, social environment, work, relationships, finances, education

Developing skills through engaging in reflective practice and professional development is essential. Each person is unique, which requires you as the professional to adapt to their particular circumstances. The resources below can help you develop understanding of both regulatory requirements and the diagnosis Lucy is living with.

Organisations providing information relevant to this case study

- Rethink Mental Illness: Bipolar disorder

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA): Resources – helping you understand mandatory notifications

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA): Podcast – Mental health of nurses, midwives and the people they care for

- Black Dog Institute: TEN – The essential network for health professionals

- Borderline Personality Disorder Community

- National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH): Anxiety disorders

Case study 3 summary

In this case study, Lucy’s symptoms of mental illness emerge in her teenage years. Lucy describes periods of intense mood, both elevated and depressed, as well as potential anxiety-related responses. It is not until she develops a therapeutic relationship with a university school-based counsellor that she realises it might be beneficial to engage the services of a psychiatrist. After she is diagnosed with bipolar affective disorder she engages in treatment. Lucy shares her experience of both inpatient and community treatment as well as her professional practice requirements in the context of her mental illness.

Amador, X. (2023). Denial of anosognosia in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research , 252 , 242–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2023.01.009

Engel, G. (2012). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 40 (3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2012.40.3.377

Fisher, J. (2023). Who am I? The identity crisis of mental health professionals living with mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing . Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12930

Kirsch, L. P., Mathys, C., Papadaki, C., Talelli, P., Friston, K., Moro, V., & Fotopoulou, A. (2021). Updating beliefs beyond the here-and-now: The counter-factual self in anosognosia for hemiplegia. Brain Communications , 3 (2), Article fcab098. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab098

Case Studies for Health, Research and Practice in Australia and New Zealand Copyright © 2023 by Nicole Graham is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

How these organizations are leading in making employee mental health a priority

Learn more from these case studies of successful leaders promoting mental health among workers.

- Business and Industry

- Mental Health

- Applied Psychology

Psychological evidence suggests employee mental health is a critical component for organizational functioning and success. As with any positive business outcome, promoting mental health among your workers often requires a significant investment of time and resources.

If you’re dedicated to equipping your employees and organization to thrive but you don’t know exactly where to begin your efforts, learn from these organizations, who have taken steps to prioritize employee mental health.

American Psychological Association

APA’s science-led, empathy-based culture has always informed its approach to employee mental health. To ensure employees can access psychological support necessary to thrive in their personal and work lives, APA provides a robust package of mental health benefits.

Employees can access mental health care for a low copay through APA’s insurance provider or through an additional mental health care insurer that enables employees to access any mental health professional for only a $20 copay (with the exception of employees enrolled in a high-deductible Health Savings Account plan, to which APA contributes).

In addition, APA’s employee assistance program provides employees and their household members with free, confidential, 24/7 support to help with personal or professional matters that may interfere with work or family responsibilities.

APA found new opportunities to build on its ongoing dedication to employees’ mental health and well-being during the Covid -19 pandemic, starting by ramping up internal communications that instilled a much-needed sense of belonging during the transition to remote work and continues to solicit employee feedback that informs organizational policies, programs, and procedures. For example, the daily staff e-blast, APA Today , is now shared in video and text format, staff share fun personal photos through questions of the week, staff are given a few extra days off per year for strengthening mental health (in addition to a generous PTO plan), and staff can share with each other socially through themed Microsoft Teams channels and Coffee Connections meetups.

Along with considering employees’ needs and interests, new initiatives also weave in the latest psychological science about what employees and organizations need to thrive. Additionally, APA uses a cross-departmental approach to implement changes, in which experts in the areas of human resources, psychological science, employee well-being, as well as C-suite leaders, work together to communicate about employee and organizational needs and implement initiatives.

APA conducts regular “pulse” polls to survey employees about the level of support they feel from their managers and the organization and what they need to feel more supported, from computer hardware to more flexible working hours. Employees also have an opportunity to hear updates from and share concerns directly with APA’s CEO in a biweekly, virtual chat.

To address the multiple layers of stressors employees are facing, APA initiated multiple staff conversations around racism and related current events, inviting experts to speak about the issues and how to take action. Employee resource groups were formed to support employees and provide them with a community.

APA also assembled a working group to use lessons learned during the pandemic and employee feedback to plan the future of the organization’s workplace. Most employees (75%) participated, sharing their perspectives about the future of work via focus groups, conversations with leadership, pulse polls, surveys, or other forums.

In response, APA is evolving its concept of the workplace rather than simply returning to prepandemic office norms: APA established a flexible work policy that allows employees to move outside the Washington, D.C. area to one of 40 approved states, maintaining their current salary and same level of employee benefits no matter where they move. In response to employees’ desires to improve their work-life harmony, APA also implemented a Meet with Purpose campaign that encourages science-based best practices for all internal meetings. Each meeting needs to have a designated agenda, start on the hour or half-hour, and last for 25 or 50 minutes to ensure employees have breaks between meetings to tend to personal or family needs. Employees are also encouraged to consider and communicate to the team about whether video is required for a meeting or if it can be audio-only, since back-to-back video meetings can have a negative impact on employee well-being.

Blackrock, an international investment management organization, also recognized the urgency of prioritizing employee well-being during the Covid -19 pandemic. As the organization pivoted to remote or socially distanced work, it conducted periodic employee surveys to gather feedback that would inform new policies and procedures.

For example, Blackrock extended its health care coverage to ensure employees working out-of-state or out of the country, along with their families, could access health care. To better support employees’ mental well-being, Blackrock onboarded a new employee assistance provider to help deliver a range of new mental health benefits, including care navigation, easy online appointment booking, virtual care delivery, and a high-quality network of providers integrated into its medical plans. The firm also offered a company-paid subscription to the Calm app and launched a peer network of Mental Health Ambassadors.

To support employees with family responsibilities, the organization expanded the number of company-paid back-up care days, implemented more flexible work-from-home schedules, and encouraged the use of the existing flexible time off policy that allows all employees—regardless of title or tenure—access to paid time off as needed. To encourage employee collaboration, Blackrock also created online forums for sharing ideas and resources to support parenting and childcare.

Building on psychological research about the importance of manager support, Blackrock launched a series of enablement sessions to train supervisors in keeping their teams informed and motivated. The firm also created an intranet resource hub to streamline internal communications, so employees can quickly access information they need to do their jobs well and ask for help as needed.

YMCA of the USA

YMCA of the USA, (Y-USA), the national resource office for the nation’s YMCAs, pivoted to fully remote work in March 2020. Recognizing the increased need for social and emotional support, YMCA immediately began heavily promoting its employee assistance program (EAP) services through frequent newsletters, emphasizing free access to confidential services for employees’ entire families.

To learn more about additional unmet needs, Y-USA leaders also utilized pulse surveys in which employees rate various areas of well-being. Using this feedback, leaders made distinct efforts to implement changes. For example, when one survey found that many work-from-home employees needed additional office equipment to perform their jobs well, the organization provided it. Another survey made clear that employees weren’t ready to return to in-office work in 2021, so YMCA changed its plans and extended its flexible work policies.

In response to employee concerns about lack of camaraderie, Y-USA created weekly virtual Coffee Chats to connect employees with one another and Tech Tuesdays, an opportunity for employees to learn or refresh tech skills, ask tech questions, and learn about efficient hybrid work practices.

Biannual culture surveys conducted by a third party also guide Y-USA’s practices. To continue to ensure employee feedback is carefully implemented, Y recently formed a Culture Counsel of volunteer employees, who help review areas for improvement and discuss possible changes. After learning of employees’ continued desire for work flexibility, organization leaders extended the work-from-home practice, encouraging employees to visit the office as needed.

In addition, Y-USA convened a Mental Health Thought Leader Cohort, made up of local Y staff who curate and package “To Go” mental health kits, a grab and go resource for local Y leaders to implement with staff, such as “Dinner Table Resilience” which offers short videos, tools, and strategies for Y-USA staff and members to use at the dinner table with families to build resilience skills.

F5 Networks

F5 Networks, a large technology company in the Seattle area, also uses employee surveys extensively to promote its “human-first, high-performance” culture. Along with regularly surveying existing employees, leaders also seek input from candidates who weren’t hired, employees who left the company, and individuals who left and came back.

After learning how growth opportunities led to employee retention, F5 developed a company-wide mentorship program, increased its budget to allow employees to pursue continued education in their field, and created quarterly learning days on which employees have no internal meetings but instead focus on learning.

In response to an increased need for time off—without the stress of returning to an inbox full of emails—F5 also launched company-wide quarterly wellness weekends allowing all employees an extra paid consecutive Friday and Monday off.

Ongoing survey data suggest positive business outcomes. F5 employees report feeling more refreshed and ready to tackle projects when they return to work after time off, for example. In general, F5 staffers report feeling supported by their managers and the organization as a whole.

On its U.S. medical plans, F5 also removed out-of-network restrictions for psychotherapy to ensure employees could connect with diverse therapists and therapists not accepting insurance. Rather than paying a large deductible and being partially reimbursed for services, employees on the Preferred Provider Organization plan pay a $15 copay for any therapist (plus any additional fees if the therapist charges more than what the benefits cover). Additionally, F5 increased its EAP therapy visit max from three to five annual sessions per employee.

Ernst & Young

The consulting firm Ernst & Young (EY) offers a full suite of mental health and well-being resources for employees and their families. In addition to EY’s health care plan that includes mental health benefits, EY has an internal team of clinicians that conduct presentations and interactive sessions promoting mental health in the organization.

EY also works with a private vendor to offer up to 25 psychotherapy sessions for each employee and each person in their household per year. Because employees’ family lives can impact their well-being and work performance, the firm extended the mental health benefit to include all family members in the household including children, domestic partners, and relatives, regardless of their age or whether they’re on the employees’ health care plan. The network of clinicians represent a variety of backgrounds that can meet employees’ diverse needs. They use evidence-based psychotherapy practices to ensure the best outcomes.

EY recognizes the role of psychological concepts like resilience in staving off stress and burnout. EY allows employees to access mental health coaching sessions to prevent issues that could interfere with well-being and work performance and increase overall well-being in their daily lives. Data suggest employees working with a mental health coach or therapist saw an 85% improvement or recovery from the initial reason they sought care.

For people who would rather use digital tools, EY offers a positive psychology-informed app that educates employees about coping with stress and promoting resilience through articles and activities. Similarly, a digital sleep resource provides personalized guidance for improving sleep. On average, people using this digital tool are getting an average of four more hours of sleep per week.

An internal initiative called We Care educates employees on important topics such as recognizing signs of mental health concern and addiction and best practices for offering support. Employees share their own mental health stories to destigmatize the topic. To encourage time away from work, EY also reimburses employees for vacations and travel; the company also reimburses for physical wellness-related activities, such as gym memberships, fitness equipment, and even mattresses.

National League of Cities

The National League of Cities (NLC), the nonprofit advocate for municipal governments, is committed to supporting and nurturing a work culture that prioritizes the mental and physical health of its employees. It has done so through several targeted approaches. Like many organizations, NLC moved its entire 130-person Washington, D.C.-based staff to virtual work at the start of the pandemic. Employees were encouraged to maximize and leverage flexible schedules. As the pandemic evolved, NLC developed a hybrid model in which staff could continue to work remotely and also use the NLC offices for collaboration and other onsite work.

The organization’s health insurance plan covers mental health services on par with its coverage of physical health. NLC subsidizes coverage for employees and family members, including access to licensed mental health providers who offer services via telehealth. NLC also offers an EAP, which it promotes regularly (and even more frequently during the pandemic) to employees.

At the start and during the height of the pandemic, NLC gathered employee input. NLC surveyed employees in 2020 and 2021 to learn about their telework experience and hear their return-to-office concerns and suggestions. More than 90% of the staff participated. To determine the cultural norms for hybrid work, NLC used a dispersed decision-making method that employed focus groups to gather ideas from every employee in the organization. One resulting cultural norm the company has established, is that employees are highly encouraged to use their paid time off from work to unplug and refresh.

American Public Health Association

The American Public Health Association (APHA), a Washington, D.C.-based organization for public health professionals, champions the health of all people and all communities.

When Covid -19 struck, APHA’s staff worked harder than ever to develop essential Covid -19 resources for members. At the same time, employees were experiencing the loss of loved ones, isolation, racial inequity, financial burden, family job loss, and the need to provide around-the-clock family support. These strains caused a real need for mental health services and support.

How does APHA support its staff? APHA’s EAP, a free service for staff, offers three immediate counseling sessions with a licensed mental health professional. Staff can access EAP professionals 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The EAP can also provide legal assistance, online will preparation, financial tools and resources, help addressing substance misuse and other addictions, as well as resources for dependent and elder care.

APHA’s mental health services through their insurer, CareFirst, are tailored for short-term and long-term mental health matters. Employees and covered family members seeing in-network professionals have no copayments and many of the providers offer telehealth visits from 7 a.m.–11 p.m. Eastern time, 7 days a week. The average therapy appointment is about 45 minutes. Psychiatrists are also available to help with mental health conditions requiring medication management.

Staff are encouraged to voice their needs. APHA instituted several internal services and activities to improve how management listened and responded to employee needs. “Courageous Conversation,” started after the George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests, are discussions with peers in an honest and safe environment about experiences that relate to race. During the height of the Covid -19 pandemic, Half-day Fridays gave staff a mental health break from the stress of having inseparable work and home space. A mindfulness video APHA shared with staff reminded them to be present in the moment, take a breath, and tackle one thing at a time. While working from home, No Meeting Tuesday Afternoons ensured staff had a block of time to focus on one task at a time as they navigated the stresses of the pandemic and increased virtual meetings. Optional forums and surveys allowed staff to communicate their mental health needs and challenges. Complimentary Stretch Class—a free monthly service—gives staff a 45-minute break to relieve stress and tension.

5 ways to improve employee mental health

Supporting employees’ psychological well-being

Striving for mental health excellence in the workplace

Acknowledgments

APA gratefully acknowledges the following contributors to this content.

- Tammy D. Allen, PhD, professor of industrial and organizational psychology at the University of South Florida

- Christopher J. L. Cunningham , PhD, professor of industrial-organizational and occupational health psychology at University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

- Gwenith G. Fisher, PhD, associate professor of occupational health psychology at Colorado State University

- Leslie Hammer , PhD, professor of occupational health psychology at Oregon Health & Science University and codirector of the Oregon Healthy Workforce Center

- Jeff McHenry, PhD , principal at Rainier Leadership Solutions and faculty member at USC Bovard College

- Jon Metzler, PhD, director of human performance at Arlington, Virginia-based Magellan Federal

- Fred Oswald, PhD , professor of industrial and organizational psychology, Organization and Workforce Laboratory, Rice University

- Dennis P. Stolle, JD, PhD, senior director of APA’s Office of Applied Psychology

- Ryan Warner , PhD, founder and chief executive officer of RC Warner Consulting in Albuquerque, New Mexico

Make a commitment to mental health excellence in the workplace

Organizational leaders are well-positioned to influence a positive culture shift and normalize mental health in the workplace.

You may also like

- HR Most Influential

- HR Excellence Awards

- Advertising

Search menu

Rachel Muller-Heyndyk

View articles

Case study: Mental health support led by the individual

Monzo wanted to ensure a range of help is available to all employees, wherever and whenever they want it

The organisation

Formed in 2015, Monzo started as a prepaid card that could be topped up via an app to enable users to make free cash withdrawals abroad. It quickly built up a strong following, and after being given the green light by the Financial Conduct Authority became a fully-fledged banking brand in 2017. Its prepaid card system has since closed, with users upgraded to its current account. Last year Monzo was named a ‘best buy’ for current accounts by not-for-profit co-operative group Ethical Consumer.

The problem

Thanks to the efforts of campaigners, businesses and charities over recent years, mental health in the workplace is now recognised as a pressing concern for employers. But while there’s far more transparency around mental health than even a few years ago, substantial progress on supporting staff has been slow in some quarters.

Research from Business in the Community in September found that of 4,000 employees surveyed, 39% had experienced poor mental health due to their work, while 33% of those with mental health problems felt ignored. Even more worryingly, 9% had been subjected to disciplinary action, demotion or dismissal after disclosing their mental health issues.

Monzo’s head of people Tara Mansfield is determined that nothing like this happens at her company, and that mental health support isn’t treated as an afterthought.

“When it comes to poor mental health you know that it’s something everyone has [at some point], and there will inevitably be people who are struggling in your team,” she says.

Mental health support for staff makes sense both ethically and strategically for organisations, she adds.

“We’re an ethical company. I’m really proud that we’re able to offer advice on financial wellbeing to our customers, and act in a responsible fair way. For me it’s about making sure that we apply the same values to the workforce.”

Mansfield knew that any support on offer at Monzo needed to be as holistic as possible, because poor mental health is experienced differently by each individual.

“If you just focus on one area of mental health there’s always going to be a risk that you alienate someone,” she explains.