Architectural Photography | The Art of Capturing Structures

Architectural photography, at its core, is the art of capturing buildings and structures in a way that is both aesthetically pleasing and accurately representative. It’s not just about taking photos of buildings; it’s about conveying the essence, design, and context of those buildings. From the towering skyscrapers that define a city’s skyline to the intricate details of a historic church, architectural photography tells the story of spaces and places.

1. Introduction to Architectural Photography

1.1. historical evolution.

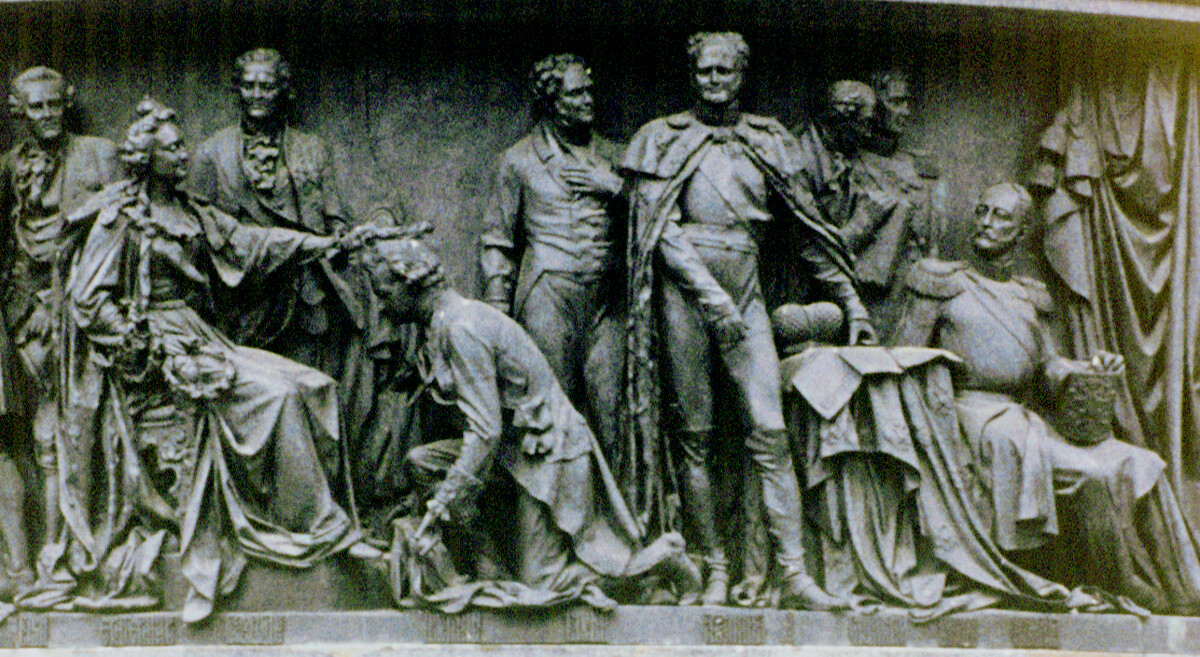

The history of architectural photography can be traced back to the early days of photography itself. In the 19th century, as the camera became more accessible, photographers began to document the world around them, including the built environment. Early architectural photographers like Eugène Atget in Paris and Julius Shulman in the USA captured not just buildings, but the spirit of the age, reflecting societal changes, technological advancements, and cultural shifts.

Over the years, as architectural styles evolved, so did the techniques and approaches to photographing them. The rise of modernist architecture in the 20th century, for instance, brought with it a new way of seeing and documenting buildings, focusing on clean lines, geometric shapes, and the interplay of light and shadow.

1.2. Importance in Today’s Digital Age

In today’s digital age, architectural photography has taken on even greater significance. With the proliferation of platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, and architectural blogs, there’s an ever-growing audience eager to consume visually striking images of architecture. These platforms have also provided a space for both professional architectural photographers and amateurs to showcase their work, share their perspectives, and engage with a global community.

Moreover, in the realm of real estate, tourism, and architectural design, high-quality architectural photography plays a pivotal role. It can influence property values, attract tourists, or even sway public opinion on new architectural projects. In essence, architectural photography serves as a bridge, connecting people to places, and stories to structures.

2. Deep Dive into Architectural Photography

2.1. characteristics of architectural photography, 2.1.1. aesthetic representation.

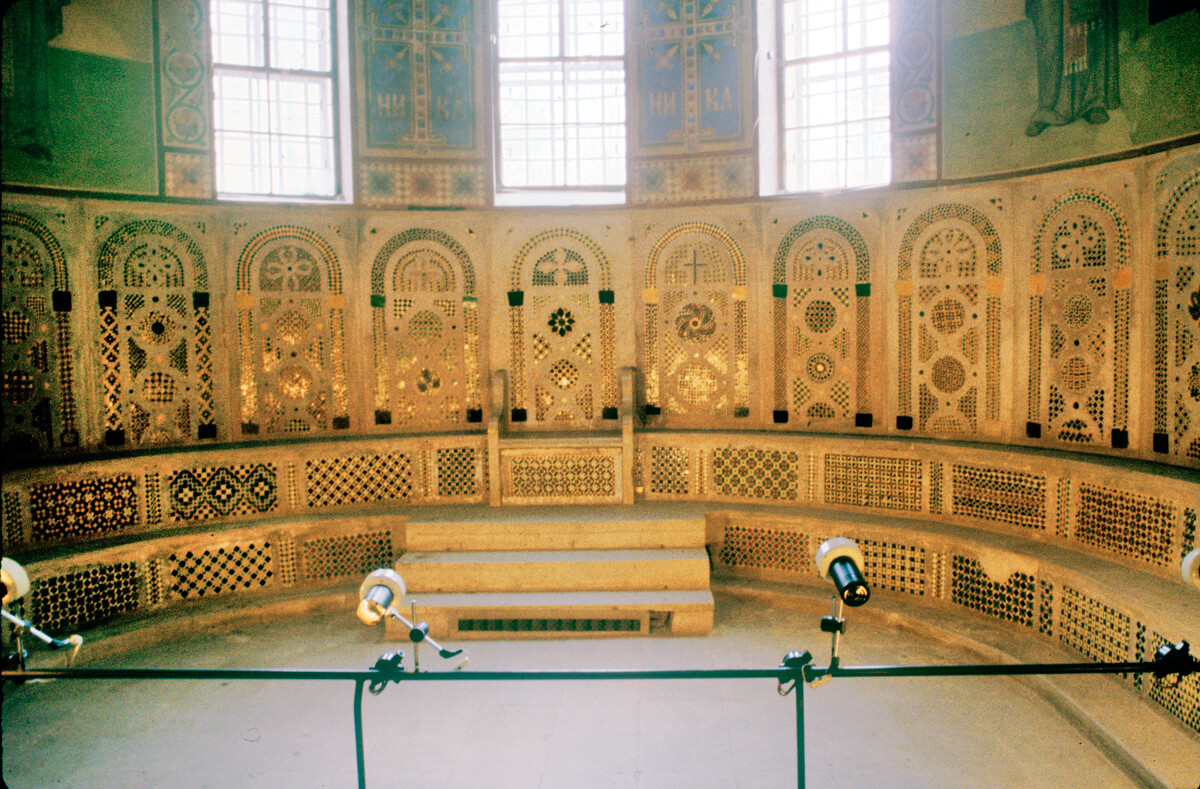

Architectural photography is not just about capturing a building; it’s about portraying its soul. The aesthetic representation involves capturing the essence of the architecture, its design philosophy, and the emotions it evokes. This requires a keen eye for detail, understanding the play of light and shadow, and recognizing the unique features that make each building stand out.

2.1.2. Accurate Depiction

While aesthetics are crucial, architectural photography also demands accuracy. This means ensuring that the building’s proportions are correct, the colors are true to life, and the context (surrounding environment) is appropriately represented. This accuracy is vital, especially for architects and designers who use these photographs as a reference.

2.1.3. Interplay of Light and Shadow

One of the defining characteristics of architectural photography is the emphasis on lighting. The way light interacts with a building can dramatically change its appearance. From the golden hues of the morning sun to the dramatic contrasts during the golden hour , understanding and harnessing light can elevate an architectural photograph.

2.2. Principles of Architecture Photography

2.2.1. perspective control.

Perspective is pivotal in architectural photography. It determines how the viewer perceives the building’s size, shape, and position. Using tools like tilt-shift lenses or post-processing techniques can help photographers control distortion and present buildings in their true form.

2.2.2. Emphasis on Design Elements

Every building has design elements that define its character. It could be the intricate patterns on a historic facade, the sleek lines of a modern skyscraper, or the unique curvature of an avant-garde structure. Recognizing and emphasizing these elements is a fundamental principle of architectural photography.

2.2.3. Contextual Relevance

A building doesn’t exist in isolation. Its surroundings, whether it’s the urban jungle of a city or the serene landscapes of the countryside, play a crucial role in its perception. Capturing this context, and understanding its relevance to the architecture, is essential.

2.3. Three Approaches to Photographing Architecture

2.3.1. documentary approach.

This approach is about capturing buildings as they are, without any artistic embellishments. It’s factual, straightforward, and often used for historical records or academic purposes.

2.3.2. Artistic Interpretation

Here, the photographer uses the building as a canvas to create a piece of art. This could involve playing with angles, lighting, or even post-processing to present a unique interpretation of the architecture.

2.3.3. Commercial Perspective

Used primarily for advertising or promotional purposes, this approach emphasizes the most attractive features of a building. It’s about showcasing the architecture in the most marketable way, often highlighting its functionality, luxury, or uniqueness.

2.4. Technical Aspects of Architectural Photography

2.4.1. best focal length and why.

The ideal focal length for architectural photography often lies between 24mm and 70mm. Wide-angle lenses (like 24mm) are great for capturing expansive buildings or interiors, while a 50mm lens offers a more natural perspective, closely resembling human vision.

2.4.2. Ideal Aspect Ratio and Its Importance

The 3:2 aspect ratio, common in most DSLRs, is often preferred for architectural shots. However, the best aspect ratio can vary based on the building’s dimensions and the desired composition . Sometimes, a 1:1 (square) or 16:9 (widescreen) might be more fitting.

2.4.3. Optimal F-stop and Its Impact

An f-stop between f/8 and f/11 is generally ideal for architectural photography. This range provides a broad depth of field, ensuring both the building and its surroundings are in sharp focus.

3. Artists in Architectural Photography

3.1. historical figures and their contributions.

- Eugène Atget : Known for his extensive documentation of Paris. His work is preserved at institutions like The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) .

- Julius Shulman : Celebrated for his photographs of Californian architecture. His collection can be found at the Getty Research Institute .

3.2. Contemporary Artists and Their Unique Styles

- Iwan Baan : Recognized for his documentary-style approach, capturing the life and culture surrounding architecture.

- Helene Binet : Celebrated for her black-and-white images, emphasizing the interplay of light and shadow.

3.3. Instagram Stars in Architectural Photography

- Fernando Guerra ( @fernandogguerra ): His feed showcases modern architecture, candid moments, and aerial shots.

- Anna Devís and Daniel Rueda ( @anniset & @drcuerda ): Known for their imaginative and playful architectural photographs.

- Mike Kelley ( @mpkelley_ ): An architectural and interiors photographer known for his unique style.

- Romain Laprade ( @romainlaprade ): He captures buildings with a focus on light, color, and texture.

- Minimal Motifs ( @minimalmotifs ): His feed is a blend of minimalism and architectural brilliance.

- Derek Swalwell ( @derek_swalwell ): An Australian photographer capturing both architecture and landscapes.

- Nicanor García ( @nicanorgarcia ): He captures the essence of urban architecture, often focusing on geometry and symmetry.

- Sebastian Weiss ( @le_blanc ): His feed is a testament to the beauty of architectural details.

4. Critical, Aesthetic, Philosophical, and Social Aspects of Architectural Photography

4.1. aesthetics and philosophy of architectural photography.

- Architectural photography is not just about capturing a building; it’s about capturing the essence of a structure. The way light interacts with surfaces, the shadows cast by intricate details, and the overall form of the structure play crucial roles in the final image. This dance of light and shadow can transform a mundane structure into a work of art.

- Perspective plays a pivotal role in architectural photography. The angle from which a building is captured can entirely change the viewer’s perception. Wide-angle lenses can exaggerate features, while telephoto lenses can compress space. The choice of perspective can either enhance or distort reality, making it a powerful tool in the hands of the photographer.

4.2. Social Implications and Representations

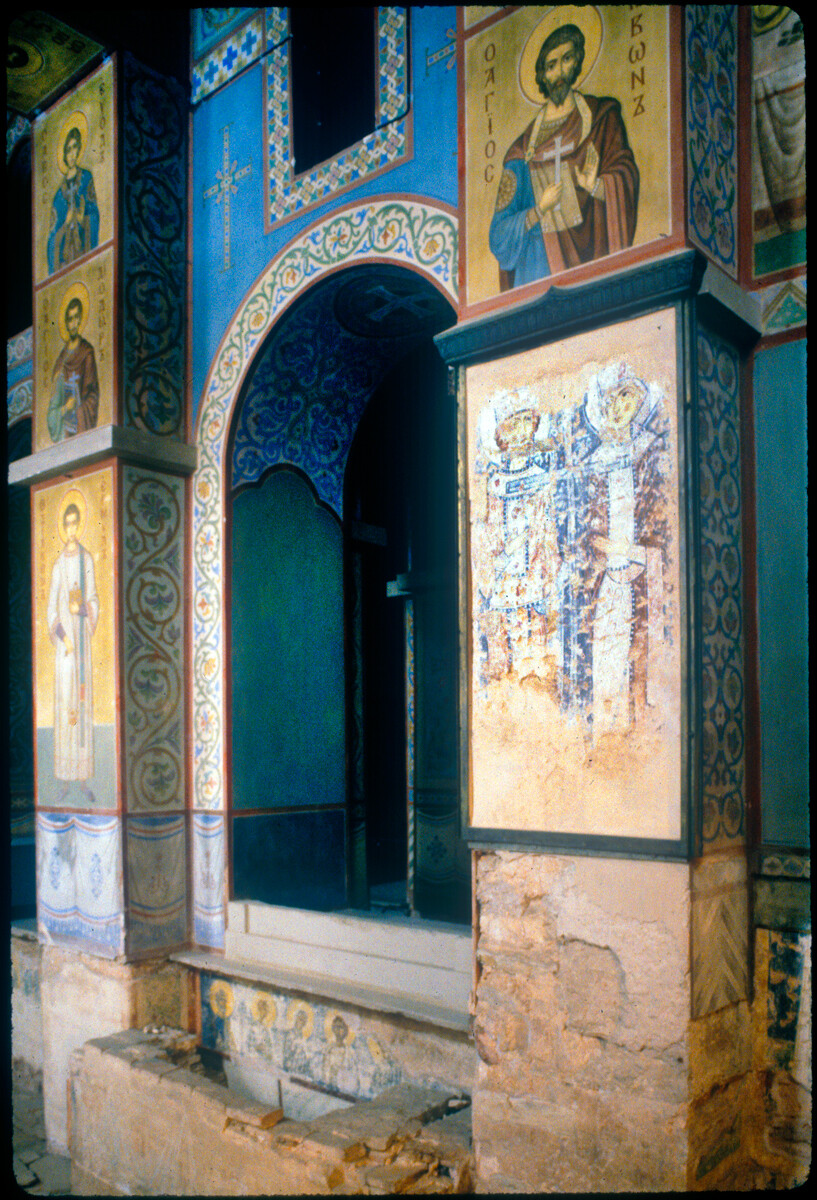

- Buildings are not just physical structures; they are manifestations of the era, culture, and society in which they were built. Through architectural photography, one can trace the evolution of societal values, technological advancements, and artistic movements. For instance, the grandeur of Gothic cathedrals speaks of religious fervor, while the sleek lines of modern skyscrapers reflect technological progress and urbanization.

- The cultural and historical context of a building can add layers of meaning to a photograph. Capturing remnants of ancient civilizations or structures that have withstood wars and natural calamities can evoke emotions of awe, nostalgia, and reverence.

4.3. Critical Analysis and Interpretation

- Just as in any art form, there’s often a gap between the photographer’s intent and the viewer’s interpretation. While the photographer might aim to highlight certain architectural features or the play of light, the viewer might be drawn to the mood or the memories the image evokes. This duality adds depth and richness to the field of architectural photography.

- Over the years, the critique of architectural photography has evolved from merely assessing technical proficiency to analyzing artistic expression, narrative strength, and contextual relevance. Modern critiques often delve into the socio-political implications, environmental context, and the ethical considerations of the images.

4.4. Ethical Considerations in Architectural Photography

- In the age of digital photography and advanced post-processing tools, the line between authenticity and manipulation can blur. While minor edits to enhance an image are generally accepted, significant alterations that misrepresent a structure can be ethically questionable. It’s crucial for photographers to strike a balance between artistic expression and truthful representation.

- Photographers wield the power of representation. Through their lens, they can either celebrate or critique architectural marvels. However, with this power comes the responsibility to represent structures and spaces without bias, ensuring that the essence of the architecture is neither diluted nor exaggerated.

5. Becoming a Professional Architectural Photographer

5.1. starting out in architectural photography.

- Building a Portfolio: Start by photographing local buildings, landmarks, and structures to showcase your skills.

- Continuous Learning: Attend workshops, online courses, and seminars to hone your skills. Websites like Udemy and Coursera offer courses in architectural photography.

- Networking: Join photography clubs, online forums, and attend industry events to connect with fellow photographers and potential clients.

5.2. Earning Money from Architectural Photography

- Freelancing: Offer your services on platforms like Upwork or Freelancer .

- Collaborate with Real Estate Agencies: Real estate agents often require high-quality photographs of properties for listings.

- Work with Architecture Firms: Partner with architecture firms to photograph their completed projects for their portfolios.

5.3. Sharing Your Work and Gaining Feedback

- Online Portfolios: Create a personal website to showcase your work. Platforms like Squarespace or Wix can help.

- Social Media: Share your work on platforms like Instagram, Pinterest, and Facebook to gain visibility.

- Photography Forums: Websites like DPReview and PhotographyTalk allow you to share your work and receive feedback from fellow photographers.

5.4. Proposing Your Services

- 5.4.1. Local Advertisements: Advertise your services in local newspapers, community boards, and online classifieds.

- 5.4.2. Online Directories: List your services on directories like Photography Directory or Photographer’s Directory .

5.5. Potential Earnings in Architectural Photography

- 5.5.1. Factors Influencing Earnings: Location, experience, specialization, and client base can significantly impact earnings.

- 5.5.2. Average Earnings: While earnings can vary, beginner architectural photographers can expect to earn between $30,000 to $50,000 annually, with experienced photographers earning upwards of $100,000.

6. Equipment for Architectural Photography

6.1. Cameras and Lenses: Recommendations and Reviews

- Full-frame DSLRs : These cameras offer superior image quality and are ideal for architectural photography. Examples include the Canon EOS 5D Mark IV and the Nikon D850 .

- Mirrorless Cameras : These are lightweight and also offer excellent image quality. Examples include the Sony A7R IV and the Fujifilm GFX 100 .

- Tilt-shift Lenses : These lenses allow for perspective control, making them perfect for architectural photography. Examples include the Canon TS-E 24mm f/3.5L II and the Nikon PC-E NIKKOR 24mm f/3.5D ED .

- Wide-angle Lenses : Essential for capturing expansive structures. Examples include the Sigma 14-24mm f/2.8 DG HSM Art and the Tamron 15-30mm f/2.8 Di VC USD G2 .

6.2. Tripods, Drones, and Other Accessories

- Tripods : Essential for stability, especially in low light conditions. Recommended brands include Manfrotto and Gitzo .

- Drones : For capturing aerial views of architectural marvels. Top picks include the DJI Mavic 2 Pro and the Autel Robotics EVO II .

- Filters : Polarizing filters can enhance architectural photographs by reducing reflections and amplifying the sky’s vibrancy. Brands like Hoya and B+W are renowned for their quality.

6.3. Post-Processing Software and Tools

- Adobe Lightroom : A favorite among photographers, Lightroom offers tools for color correction, lens profile adjustments, and basic editing.

- Adobe Photoshop : An advanced tool for intricate edits, Photoshop allows for perspective alterations and image compositing.

- Capture One : Known for its exceptional color grading capabilities, Capture One is a top choice among architectural photographers.

7. Conclusion

Architectural photography, as we’ve explored, is not just the act of capturing buildings but an intricate dance of light, shadow, and perspective. It’s a genre that tells stories, encapsulating the essence of eras, cultures, and the visions of architects. From the grand Gothic cathedrals that speak of a bygone era’s religious fervor to the sleek modern skyscrapers symbolizing technological progress and urbanization, every photograph holds a narrative.

The journey through the technicalities, from understanding the best equipment to the nuances of focal lengths and aspect ratios, underscores the depth and complexity of this field. It’s not just about having the right gear but knowing how to use it to bring a structure to life. The interplay of aesthetics, philosophy, and the socio-cultural implications further elevates architectural photography from mere documentation to an art form.

Artists, both historical figures like Atget and Shulman and contemporary Instagram stars, showcase the genre’s vast range and potential. Their works, diverse in style and approach, offer inspiration and a benchmark for aspiring photographers.

However, as with any art form, architectural photography raises questions. In an age of digital manipulation, what is the line between authenticity and artistic interpretation? How does one balance commercial demands with artistic integrity? And as the world continues to urbanize, how will architectural photography evolve to reflect changing landscapes and societies?

The world of architectural photography is vast, intricate, and ever-evolving. As we stand at this intersection of art, history, and technology, one can only wonder: What’s the next chapter in this captivating story? What new narratives will the future structures and their photographers tell?

8. Further Reading

For those who have been captivated by the world of architectural photography and wish to delve deeper, literature offers a treasure trove of insights, techniques, and inspirations. Here are some seminal works that are considered essential for anyone passionate about this genre:

- A comprehensive guide that covers both the technical and artistic aspects of architectural photography. Schulz delves into the nuances of composition, the intricacies of capturing light and shadow, and the post-processing techniques that can elevate an image from good to great.

- Amazon Link

- A classic in the field, this book offers invaluable advice on capturing architectural marvels. McGrath, with his decades of experience, provides insights into the challenges and rewards of photographing buildings, interiors, and exteriors.

- This book is an exploration of the relationship between architecture and photography. Redstone curates works from renowned photographers, showcasing how they interpret space, form, and design. It’s a visual treat and a deep dive into the artistic side of architectural photography.

- Elwall takes readers on a historical journey, tracing the evolution of architectural photography. From its early days to the modern digital era, the book offers a comprehensive look at how architectural photography has documented and influenced the way we see buildings.

For those embarking on this journey, these books not only offer knowledge but also inspiration. They serve as a reminder of the beauty and complexity of architectural photography, urging readers to see buildings not just as static structures but as stories waiting to be told.

9. Useful Links for Architectural Photography Enthusiasts

Navigating the vast world of architectural photography can be overwhelming. To help you on your journey, we’ve compiled a list of valuable resources that will provide you with further insights, techniques, and inspiration:

MoMA – The Museum of Modern Art’s Photography Department :

- The MoMA in New York City houses an extensive collection of photographs, including architectural photography. Their collection spans the history of the medium and includes works from many renowned architectural photographers.

- Visit MoMA’s Photography Department

Getty Research Institute :

- The Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles is dedicated to furthering knowledge and advancing understanding of the visual arts. Their vast resources include collections on architectural photography, which can be a treasure trove for enthusiasts and researchers alike.

- Explore Getty Research Institute

AA School’s Library :

- The Architectural Association School of Architecture in London has a rich library that offers a plethora of resources on architectural photography. It’s a great place to delve deeper into the subject.

- Visit AA School’s Library

- RIBApix is the Royal Institute of British Architects’ image platform, which showcases a vast collection of architectural photographs. It’s an excellent resource for both inspiration and research.

- Explore RIBApix

ArchDaily :

- ArchDaily is one of the most visited architecture websites worldwide. It provides daily news, projects, products, and events tailored to the interests of architects. Their vast collection of articles and photographs can be a great resource for architectural photography enthusiasts.

- Visit ArchDaily

Architizer :

- Architizer connects architects with the tools they need to build better buildings, better cities, and a better world. Their platform is filled with architectural projects, products, and news, making it a valuable resource for architectural photographers.

- Explore Architizer

B&H Photo Video :

- For those looking to purchase or upgrade their photography equipment, B&H is one of the largest non-chain photo and video equipment stores in the US. They offer a wide range of products and also have a plethora of articles and tutorials on architectural photography.

- Shop at B&H Photo Video

Remember, the world of architectural photography is vast and ever-evolving. These resources are just a starting point. As you delve deeper into this fascinating subject, you’ll undoubtedly discover many more valuable tools and platforms to aid your journey.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

David Campany

Architecture as photography, constructing worlds: photography and architecture in the modern age, barbican gallery / prestel, 2014.

‘Architecture as Photography: document, publicity, commentary, art’.

An essay written for the book accompanying the exhibition Constructing Worlds: Photography and Architecture in the Modern Age , Barbican Gallery London, 25 September 2014 – 11 January 2015; ArkDes Stockholm, 20 February – 17 May 2015; Museo ICO Madrid, 3 June – 6 September.

A Spanish translation, ‘La arquitectura a través de la fotografía: documentación, publicidad, crónica, arte’ is available in the book Construyendo Mundos: fotografia y arquitectura en la era moderna , published by La Fabrica.

Everyone will have noticed how much easier it is to get hold of a painting, more particularly a sculpture, and especially architecture, in a photograph than in reality.

Walter Benjamin [i]

It may not be possible to ‘get hold of’ a building, at least not in the way that it might be possible to get hold of a painting or a sculpture. But through photography one might be able to get hold of architecture. By this I mean, and perhaps the cultural critic Walter Benjamin meant, that while a physical building is owned and used, a photograph of it is able to isolate, define, interpret, exaggerate or even invent a cultural value for it. We might even go so far as to say that the cultural value of buildings is what we call ‘architecture’ and that it is inseparable from photography.

Walter Benjamin was writing in 1931, a decade or so into the expansion of the modern mass media. Via illustrated magazines and books, photography was establishing and spreading cultural value. Anything and everything was to be photographed and arranged on the page as a new and perhaps spurious kind of ‘visual knowledge’. Just as Benjamin went on to suggest that the kind of art that will triumph will be the kind of art that looks good in photographic reproduction, architecture will not escape the same fate. In fact he concluded that buildings might be the ultimate art works in this new regime of the image. Of all the fine and applied arts it is built form that has the most to lose to photography (because the camera can never capture it, never ‘get hold of’ it) but as a consequence it also has the most to gain.

Emerging in Europe after the First World War, Modernist architecture travelled unevenly but globally via the printed page. For example, the establishment of what came to be called the International Style could not have happened without photography. Moreover, it is often argued that it was through Modernism that architecture became profoundly, perhaps irreversibly complicit with its camera image. Architects began to design with photographic representation in mind and for good or bad the public began to understand the built world around them in photographic terms.[ii]

View from the Window at Le Gras by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, 1826-27.

We should remember photography’s attraction to architecture goes back to the very earliest camera pictures. Nicéphore Niépce’s View from the Window at Le Gras (1826) was a lucid demonstration of the new medium’s consummate translation of three dimensions into two, although it lacked the detail that soon became so characteristic. Here is Sir John Robison responding to his first view of a group of fine Daguerreotype images in 1839:

‘The perfection and fidelity of the pictures are such that, on examining them by microscopic power, details are discovered which are not perceivable to the naked eye in the original objects, but which, when searched for there by the aid of optical instruments, are found in perfect accordance; a crack in plaster, a withered leaf lying on a projecting cornice, or an accumulation of dust in a hollow moulding of a distant building, when they exist in the original, are faithfully copied in these wonderful pictures.’ [iii]

In noting the cracks and dust, Robison had grasped that the technology of photography belonged to a different order from the aged world around it. Even so, that aging – patina and ruination – was thoroughly photogenic. Through the camera an old building would be subject to ‘a clash with a time not its own.’[iv] Since then, photography has been put to use recording the world’s older buildings and ruins. It has also been used to document and promote new constructions that very much do belong to the time and technology of photography: Victorian bridges and glasshouses, monuments and towers in steel, high-rises and high-tech buildings.

Time and surfaces

While Modernist architecture celebrated industrial smoothness, Modernist photography explored a heightened interest in the surfaces of the world. A gleaming facade and the cracked hands that built it offer themselves up equally to a perfected lens and a glossy print or page. In 1924, Edward Weston, the supreme artist-technician of the high-modern photographic surface, declared: ‘The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh.’[v] The same year, László Moholy-Nagy spoke of photography’s rendering of ‘the precise magic of the finest texture: in the framework of steel buildings just as much as in the foam of the sea.’[vi] And in 1930 Pierre Mac Orlan observed: ‘On the photosensitive plate, polished steel finds a still sleeker interpretation of its shining richness.’[vii]

Eugène Atget, Rue de Sein e, Paris 1924

Mac Orlan was writing in a book of photographs by Eugène Atget. Those pictures contained no polished steel. To the contrary, Atget had turned his camera on the remnants of old Paris that had escaped the clash with the modern wrecking ball: old cafés and shop fronts, specimens of historic architecture, conjunctions of buildings accumulating over centuries into ad hoc neighbourhoods. Atget understood the urban fabric as something that exists over generations and is altered by use and weather. Photography and architecture were for him complex repositories of time. There was plenty of polished steel elsewhere in modern cities such as Paris, and plenty of photographers who saw their medium as its publicist or go-between.

Atget made his images quietly, usually on commission but also for himself. He may not have considered photography to be art but it was certainly an art. The medium was unique in its allowing for the intelligent balance of document and interpretation. Atget made images that seemed to lack explicit motive but shared a general condition of openness – a rhetorical muteness, let us say – that awaited completion by whoever bought and used them (industrial designers, urban planners, artists). The Surrealists appreciated Atget’s evocation of a haunted city with its architecture at once inhabited and seemingly dispossessed. And they saw something of their desire for subversion (and subversion of desire) in those laconic and unadorned vistas.

Atget lived on the same street as Man Ray whose darkroom assistant, Berenice Abbott, was captivated by Atget’s pictures. Upon his death in 1927, Abbott acquired a substantial part of Atget’s archive. She took it back to New York where she exhibited it, published two books of it and eventually bequeathed it to the Museum of Modern Art.[viii] Atget’s contemplative disposition struck a chord with those seeking a more reflective relation to architecture, modern time and the city. The 1929 American stock market crash and ensuing crises sharpened the political and social consciousness of many artists. As a result, an equivocal take on progress – looking askance or awry at the white heat of modernisation – became an important part of serious photography. When Berenice Abbott began her own urban documentation in 1935, it was very much in the spirit of Atget. She published her grand project in 1939 as Changing New York . She wrote: ‘How shall the two-dimensional print in black and white suggest the flux of activity of the metropolis, the interaction of human beings and solid architectural constructions, all impinging upon each other in time?’ Abbott mixed images of new buildings with older examples, making bold views in which Manhattan’s layered epochs of beauty and ugliness, of boom and bust, were laid bare. A striking example is House of the Modern Age, Park Avenue & 29th Street (1936).

Berenice Abbott, House of the Modern Age, Park Avenue & 29th Street (1936)

Beneath a cluster of towers of varying merit nestles a two-storey show home built with the latest techniques and equipped with state-of-the-art gadgets. The public paid 10 cents each to visit the ten-thousand-dollar house, erected on a million-dollar vacant lot. The house was temporary but Abbott’s photograph preserves the event and offers a pause for reflection. While America’s offices went skyward, its homes would sprawl laterally to become an endless suburbia. The theatrical singularity of that show home belies the sheer quantity and formulaic repetition that came to dominate twentieth-century housing.

Abbott was friendly with Walker Evans, who took up photography in the late 1920s. At first the giant architecture of Manhattan attracted him. He made celebratory images of soaring verticals, dynamic angles and grid-like facades. They were reminiscent of the European New Vision photography of Moholy-Nagy and others, but like Abbott he soon stepped back to develop a more circumspect attitude. Modish affectation gave way to a more neutral, less forced way of thinking and photographing. He focused on provincial towns away from the extravagance of the big cities. A commission to record Victorian houses around Boston allowed him to develop his approach. In 1933 the results were exhibited, essentially as documents, in the Architecture Galleries of the Museum of Modern Art.[ix] Five years later, Evans was the first photographer to be given a solo exhibition in his own name at MoMA, and more than half of his one hundred prints were architectural.

Page from ‘Photographic Studies’ by Walker Evans, The Architectural Record , September 1930

Walker Evans, Houses and Billboards, Atlanta , 1936.

Evans understood that photography and architecture are related sign systems. Gathered as archives or arranged as sequences, images of buildings could be a path toward sophisticated statements about a society and the ways it pictures itself. He used his large-format camera to cut out and miniaturize facades as surfaces to be read.[x] The reading can be symbolic, metaphorical or literal, not least because so often his photographs included writing and commercial signage. Such images can be understood as found montages that make thinkable the new tensions of modern life. Consider Houses and Billboards, Atlanta (1936). Beyond the formal elegance of the picture it is a document thick with information. It shows a brutal barrier shielding houses from the noise of the growing number of automobiles. The porches of the grand but fading homes now have a blocked view, while the upper balconies overlook a charmless strip. The movie billboards lining the barrier are designed not for the residents but to catch the eye of passing motorists. Between the houses we glimpse the flat roofs of more recent buildings, and on the right there is a light-industrial chimney. Despite some architects’ dreams of grand plans, it is pragmatism and happenstance that have defined the look of most of our towns. Evans played off his cool and steady gaze against the speed of unpredictable change, drawing attention to the composition of the world rather than his own compositional prowess. Measured, reflective and unforced, his photographs do not chase after progress: they study its visible symptoms.

Thomas Struth, Clinton Road, London , 1977

Evans swung wide the doors for generations of photographers. American Photographs , the book that accompanied his 1938 exhibition is still in print. One can work in this idiom anywhere without risk of imitation, or the anxiety of influence. For example, Thomas Struth’s city studies of the 1970s echo Evans’ generosity of seeing and his attention to the telling minutiae of the streetscape.[xi] But perhaps the clearest inheritor has been Stephen Shore, whose photographs made across the Midwestern United States in the 1970s share Evans’ affection for American vernacular culture.[xii] Made on long car trips, Shore’s photographs treat buildings and automobiles as expressions of the same social and economic forces. In 1956 the cultural critic Roland Barthes had declared:

‘I think that cars today are almost the exact equivalent of the great Gothic Cathedrals: I mean the supreme creation of an era, conceived with passion by unknown artists, and consumed in image if not in usage by a whole population which appropriates them as a purely magical object.’[xiii]

Stephen Shore, Fifth and Broadway, Eureka, California , September 2, 1974,

The aesthetic and principles of manufacture of any epoch are common to all its products. Modernity merely accelerates and integrates this. As a consequence, its architects have often been designers of other things as well: furniture, cars, trains, planes, electrical appliances, clothes and graphics. Figures as diverse as Charles Rennie Mackintosh, Mies van der Rohe, Frank Lloyd Wright, Charles and Ray Eames and Raymond Loewy were all exponents of this approach.

Julius Shulman, Case Study House No. 20, Altadena , CA. 1958, Architect Buff, Straub and Hensman

Photography is often at its most complicit when it is recruited to turn the constructed worlds of integrated design into promotional images. Julius Shulman was one of the most adept photographers of modernist environments. It is through his commissioned images that we have come to ‘know’ the work of Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, Pierre Koenig, John Lautner, Rudolf Schindler, Raphael Soriano and Frank Lloyd Wright among many others. Forms of architecture and design that have already internalised the look and cultural value of photography are distilled by Shulman into media-friendly icons. But nothing dates more acutely than high style. Like modish advertisements in old copies of Life magazine, Shulman’s photographs share the same aspiration as the designed worlds they represent and are subject to the same historical fate. Today such images do not so much promote as stand as documents of the taste and values of an era.

Second thoughts

Spread from ‘Outrage’, June 1955, special issue of Architectural Review , edited by Ian Nairn

It should be said that the architectural profession has always had misgivings about the cosy relationship between buildings and photography, and there has always been dissent. Sometimes it has taken the form of polemics against the conventions of architectural photography.[xiv] Other criticisms have emerged more implicitly within visual essays by architects and writers. For example, between the 1950s and 1970s Ian Nairn wrote excoriating attacks on the shortcomings of UK architects and planners, as well as heartfelt defences of places and ideas that were endangered or out of favour. His texts were often complemented by deliberately perfunctory images devoid of arty ingratiation. One of his most influential tirades was ‘Outrage’, a special issue of The Architectural Review from June 1955. Nairn railed against what he called the Subtopia of the post-war English landscape: ‘[A] mean and middle state, neither country nor town, an even spread of abandoned aerodromes and fake rusticity, wire fences, traffic roundabouts, gratuitous notice-boards, car-parks and Things in Fields.’ Throughout the issue, deadpan snapshots embody the laziness, cynicism and lack of vision Nairn attempts to diagnose. Sometimes a couple of photos and a caption do it all. A notorious page of ‘Outrage’ carries two near-identical views down unloved streets, one captioned ‘leaving Southampton’, the other ‘arriving at Carlisle’, with the entire length of England implied between.

Just as the discipline of art history has intermittent doubts over its use of photography as innocent reproduction, so the field of architecture has sustained an important current of reflection about its use of images. In some respects the critical discourses established in the architectural press of the post-war decades paved the way for the rise of architecture in much wider discussions of culture, politics, art and value. This in turn led several architects to understand their own practices in broader cultural terms. In 1972, Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour published Learning from Las Vegas , a provocative call for architects to be more in tune with popular taste. The profession should less heroic, less snobbish and more accepting of context and pragmatism, they argued. And they should not have their heads in the sand about the relation between money, built form and image (something perfectly explicit in Las Vegas!) The book’s mix of text and photographs placed it in a long line of widely read but serious architectural manifestos that goes all the way back to Le Corbusier’s Vers une architecture (1923), published in English as Towards a New Architecture (1927). While some see Learning from Las Vegas as an apology for raw capitalism and the market’s dictation of the environment, it can also be read as a critique of all that. In architecture the line between the genuinely popular (i.e. democratic) and the populist (pandering to lowest common denominators of value) is particularly fine and requires constant vigilance.

Installation view, showing photographs by Stephen Shore, of Signs of Life: Symbols of the American City . The Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC, 1976

Extending their ideas, Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates staged ‘Signs of Life: Symbols of the American City’ at The Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC in 1976. The exhibition approached the American urban scene as a complex puzzle in need of decoding. Many towns had become postmodern collages of architectural quotation: English village windows and Italianate brackets sharing facades with colonial ironwork and classical balustrades. In the gallery space various images were placed in relation real objects (neon signs, furniture, pieces of architecture). Stephen Shore, who was then deep into his photography of vernacular towns and buildings, was commissioned to make documents. A number of these were blown up and presented as near life-size substitutes for American streetscapes.

Like Atget, Abbott and Evans before him, Stephen Shore was interested in photographing the present for the benefit of the future. Such a task keeps the photographer alert to the interrelation of all the different components that may co-exist in an urban scene. He explains:

‘There is an old Arab saying, ‘The apparent is the bridge to the real.’ For many photographers, architecture serves this function. A building expresses the physical constraints of its materials: a building made of curved I-beams and titanium can look different from one made of sandstone blocks. A building expresses the economic constraints of its construction. A building also expresses the aesthetic parameters of its builder and its culture. This latter is the product of all the diverse elements that make up ‘style’: traditions, aspirations, conditioning, imagination, posturings, perceptions. On a city street, a building is sited between others built or renovated at different times and in different styles. And these buildings are next to still others. And this whole complex scene experiences the pressure of weather and time. This taste of the personality of a society becomes accessible to a camera.’[xv]

Or, as the television critic AA Gill puts it, ‘the built landscape is the great pop-up lexicon of who we are, humanity’s diary. It’s what we thought and hoped for.’[xvi]Yet we cannot assume that being accessible to the camera means the built landscape can be interpreted easily. Over centuries, architecture evolved symbolic languages that allowed buildings to declare their purpose, or at least codify it. Churches looked like churches, houses looked like houses, banks looked like banks and so on. However, with the beginnings of Modernism this began to be replaced by the idea that built form should follow function, along with a truth to the materials used. While this might imply a certain clarity or honesty, the modernising impulse also homogenises, tending towards rationalised modular forms that often cut the ties between function and legibility. This has been felt equally in the ‘high’ architecture of prestige buildings and the ‘low’ architecture of social housing and the factory. The modern show home photographed by Berenice Abbott in 1939 used the same principles as the modern office. In the knee-jerk reaction against such anonymity however, decoration often becomes purely cosmetic. Venturi, Scott Brown and Izenour called this the ‘decorated shed’, but decorated or not, the shed has become a source of anxiety about the runaway forces of rationalisation. Is it what we want everywhere, for everything?

Lewis Baltz, ‘North Wall Steelcase 1123 Warner Avenue Tustin, 1974’ from T he New Industrial Parks near Irvine, California , 1974

In his quintessentially postmodern movie, True Stories (1986), David Byrne plays a wide-eyed guide to a world in which surface and meaning have come apart almost entirely. ‘This is the Varicorp building, just outside Virgil’, he tells us. ‘It’s cool. It’s a multipurpose shape. A box. We have no idea what’s inside there.’ Byrne’s disarmingly jolly delivery suggests something is wrong. A decade or so earlier, the California-based photographer Lewis Baltz had come to the same conclusion. His series The New Industrial Parks near Irvine, California (1974) documents the exteriors of small and medium sized industrial units of the kind we now find clustered on the edges of all towns and cities. They are erected quickly according to standardised systems and designed to suit as many commercial needs as possible. The sparsely decorated exteriors give a thin illusion of calm and continuity. In reality the units can be rented to businesses long- or short-term, depending on the volatility of markets. This is Baltz describing his project:

‘I was born in one of the most rapidly urbanising areas in the world: Southern California in the post-war period. You could watch the changes take place; it was astonishing. A new world was being born there, perhaps not a very pleasant world. This homogenised American environment was marching across the land and being exported. And it seemed nobody wanted to confront this. I was looking for the things that were the most typical, the most quotidian, everyday and unremarkable. And I was trying to represent them in a way that was the most quotidian, everyday and unremarkable. I certainly wanted to make my work look like anyone could do it. I didn’t want to have a style; I wanted it to look as mute, and as distant as to appear to be as objective as possible … I tried very hard in this work not to show a point of view. I tried to think of myself as an anthropologist from a different solar system … What I was interested in more was the phenomena of the place. Not the thing itself but the effect of it: the effect of this kind of urbanization, the effect of this kind of living, the effect of this kind of building. What kind of people would come out of this? What kind of new world was being built here? Was it a world people could live in? Really?'[xvii]

Shot in deep focus and fine detail, Baltz’s photographs are highly descriptive, even analytical. Across his series of fifty-one images, the distances between the camera and the subject are kept consistent, as is the light. Frontal and rectilinear, these pictures do not appear to contest the presumed objectivity of photography. Indeed, they provide as good a record as any of the surfaces of the things in front of Baltz’s lens. Instead the problem of representation is displaced on to the world itself: what can we know when the appearance of our environment tells us so little about its meaning and function? As Baltz himself put it: ‘You don’t know whether they are manufacturing pantyhose or megadeath’.

Baltz came to prominence around the same time as Bernhard and Hilla Becher, who photographed in a similar manner but were interested in buildings where function was still inscribed in form and legible: lime kilns, cooling towers, blast-furnaces, winding towers, water towers, gas holders and silos. In a 1970 publication of their work, they state:

Cover of Berhard and Hilla Becher, Anonyme Skulpturen: Eine Typologie Technischer Bauten , 1970

‘We show objects predominantly instrumental in character, whose shapes are the results of calculation, and whose processes of development are optically evident. They are generally buildings where anonymity is accepted to be the style. Their peculiarities originate not in spite of, but because of the lack of design.’[xviii]

That book was titled Anonyme Skulpturen ( Anonymous Sculpture ) and through it the Becher’s work came to occupy a pivotal place at the intersection of photography, architecture and art. Its reception as art was part of a complex re-embracing of the typological series by a culture fraught with suspicion about utopian rationality. In such a setting, these cool photographic studies associated the documentary image less with the older ‘new sobrieties’ of the 1920s and ‘30s that they clearly echoed, than with the newer ambivalence of Minimalist sculpture and Conceptual Art. [xix] The serial blankness of their work looked considered and random, didactic and obtuse, familiar and odd, smart and dumb. Most artists using photography at the time were opting for the dulled aesthetic of the anonymous, ‘deskilled’ amateur, but working in the guise of trained technicians the Bechers presented an equally rich puzzle for art. Their series or grids of highly crafted images erased all traces of signature style, while even their choice of subject matter was intriguing. Those industrial structures had no place in the official discourses of architecture, let alone art. Since then of course the interest shown in the vernacular by contemporary art, and the interest shown in the vernacular and contemporary art by architecture has grown immeasurably, along with the canonical status of the Bechers’ work.

Nevertheless, it would be misplaced to assume that the Bechers’ work was particularly of its time. In fact the difficulty of defining its time seems to be the source of its enduringly slippery fascination. Beyond subject matter, the characteristic feature is the even, flat light. In such light buildings are, as Richard Sennett put it in a discussion of the work of Thomas Struth, ‘endowed with a life all their own’. [xx] Weak light makes for wilful buildings, renders them insistent but inscrutable. Light is usually the animator of the world and photography its captor, but when the light refuses animate the world appears dead, and the task that befalls the photographer is not to ‘shoot’ so much as embalm. To photograph in milky light is to photograph a world that appears to have already been plucked from time. [xxi]

That Northern Europe, the cradle of modernity’s hurtling progress is for much of the time bathed in a light that almost eliminates shadow may not be without significance. This was the preferred light for much of the rationalised and informational imagery produced in the nineteenth century, where the absence of shadow was equated with impartial judgment. Clear, soft illumination was construed as liberating the world from the prejudice of chiaroscuro and the drama of shadows. Revelling in the wealth of visible detail made available, positivist science deduced objectivity from the inscrutable, and clarity of knowledge from the clarity of appearances. The Bechers stare at things with an air of objectivity so outside fashion that their subjects almost stare back. Resisting the spectacle and modish artifice that has preoccupied Western art since Pop, they have extended and deepened the potential complexities of the impassive ‘document as art’ that were first sensed in the 1920s. Their work belongs to art and transcends it too. Moreover photography’s ticket into the art of the last hundred years has been its flirtation with non-art and the document. The Bechers’ anonymous photography of anonymous architecture fits this perfectly.

The photograph transformed

Through their teaching in Dusseldorf and through their profile in contemporary art, the Bechers have influenced generations of photographers interested in architecture. However, much of the work made in their wake has courted art much more openly and lost a degree of ambiguity on the way. For example while the Bechers infer the sculptural, much of Andreas Gursky’s globetrotting output often makes quite explicit reference to it, while the sheer size of his monumental gallery prints affords them an obvious status as exhibitable objects.

Thomas Ruff, Ricola, Mulhouse , 1994

Thomas Ruff’s architectural imagery, typified by a photograph of Herzog & de Meuron’s Ricola building in Mulhouse-Brunstatt, France, operates at a similar scale and is a complex example of the ever-closer alliance between those who make buildings and those who photograph them. In fact the Ricola building features a surface design derived from a photograph of a leaf by Karl Blossfeldt who, along with August Sander and Albert Renger-Patzsch in the 1920s, had championed the New Vision photography inherited by the Bechers. However, Ruff photographs this building at night, with the additional drama of artificial light under an acid purple sky. His image is a document, an art work and an advertisement.

Charting the increasing dominance of photography in the making, promotion and experience of architecture, the American cultural critic Fredric Jameson drew a distinction between what he saw as the openness of the architect’s drawn plans and the closed tyranny of the photograph:

‘The project, the drawing, is… one reified substitute for the real building, but a “good” one, that makes infinite utopian freedom possible. The photograph of the already existing building is another substitute, but let us say a “bad” reification – the illicit substitution of one order of things for another, the transformation of the building into the image of itself, and a spurious image at that … The appetite for architecture today … must in reality be an appetite for something else. I think it is an appetite for photography: what we want to consume today are not the buildings themselves, which you scarcely even recognise as you round the freeway … [M]any are the post-modern buildings that seem to have been designed for photography, where alone they flash into brilliant existence and actuality with all of the phosphorescence of the high-tech orchestra on CD.’[xxii]

Jameson was writing in 1991, at the cusp of a profound transformation that well-nigh collapsed the distinction between architectural design and photographic imaging. At that time several architectural firms were at the forefront of the development of computer software that would enable not just new methods of design but new modes of presentation and publicity. Today, buildings are often preceded by photorealist renderings that even mimic the characteristics of traditional lens-based images such as flare, differential focus and converging verticals. Construction sites are encircled with mural-sized depictions of buildings to come. These are photographic images with a future tense: this architecture will be.

Rut Blees Luxemburg, From the series London Dust , 2012.

Temporarily at least, the latest global recession has betrayed many such promises. For her series London Dust , Rut Blees Luxemburg has photographed the hoardings around the site of The Pinnacle, in the City of London, a particularly high-profile casualty of the halt on new construction in Europe. The planned 300-metre-high tower has stalled at the seventh floor. London Dust shows the glossy publicity fading and besmirched by the city’s incessant grime.

Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin, from the series Chicago , 2006

The simulation of buildings can also be concrete. After eighteen months of negotiations, in 2005 Adam Broomberg & Oliver Chanarin secured access to a very secret place. Codenamed Chicago, it is a mock-up Arab town built by the Israeli Defence Force for training in urban combat. Hidden from view by the inhospitable Negev desert, Chicago was where the Israeli military practiced its destruction of Palestinian settlements. Granted a matter of hours to photograph the facility, the duo chose the clearest and most optimal views; but rather than grounding this concrete reality, the extreme objectivity of their pictures has an unexpected effect. They flip us into the register of hyper-real simulation of the kind we associate with the aesthetics of ‘virtual reality’. These are the forced monocular perspectives typical of violent video game graphics with their surveying ‘point of view’ shots. Indeed, the photographs share something of the video game’s status as model – a fantasy of worldly control. What took place in Chicago was the safe rehearsal of imaginary mastery, yet these photographs are also documents of a real place which now no longer exists (the Israeli military has since destroyed it and built a new training site).

Still from Victor Burgin, A Place to Read , video projection, 2010

With its rather corporate connotations, computer-generated imaging remains largely a tool of mainstream practices, but there are examples of more overtly critical and resistant use. In 2009 the artist Victor Burgin was invited to make a piece of work in response to the city of Istanbul.[xxiii] After several visits he became interested in the Taşlik coffee house and garden, constructed in 1947-48. Designed by Sedad Hakki Eldem, on a site overlooking the Bosphorus, it blends elements of seventeenth-century Ottoman architecture with twentieth-century Modernism. It was open to everyone. Then in 1988 it was dismantled to make way for a luxury Swissôtel. Part of the coffee house was re-built but in a different position, and now serves merely as an orientalist tourist restaurant. Working from drawings and photographs, Burgin resurrected the building virtually.[xxiv] A 3D model conjures it up in all its democratic glory. Presented as a video projection titled A Place to Read , camera movements in and around the space are intercut with texts weaving together historical anecdotes and fictions that encourage the viewer to consider a brief moment in Istanbul’s passage from Empire to contemporary global capitalism. ‘A woman at the opening of the installation at the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul was in tears’, recalled Burgin, ‘she had known the original coffee house as a child.’[xxv] Burgin’s imagery promised no ‘proof’ in the traditional photographic sense, yet it elicited the same emotional charge. An image can resonate no matter what its material or technological base.

Jeff Wall, Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation , Barcelona 1999

The revisiting of a lost building through archival documents also informs Jeff Wall’s photograph Morning Cleaning, Mies van der Rohe Foundation, Barcelona (1999). The pavilion, designed by Mies van der Rohe for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, is a now a Modernist touchstone. It has a particularly complicated relationship with photography. Rather than housing an exhibit, the structure was intended to be the exhibit, a showcase for Mies’ architectural thinking and ‘an ideal zone of tranquility’, as he put it, set apart from the bustle of the Exposition. It was also intended to be temporary and within a year it was taken down. However, in the ensuing decades its reputation grew, largely through photographs and the consolidation of Mies’ reputation. In 1983 reconstruction began using photographs and original plans. The pavilion reopened in 1986 and in the 1990s several artists were invited to make responses to it, including Victor Burgin, Jeff Wall, Hannah Collins and Günther Förg. Wall photographed a man named Alejandro, one of the team of three responsible for keeping the pavilion clean. The morning routine was shot every day for two weeks, always from the same camera position. Wall’s colour photograph is a composite image that allows the all the detail of the shadows and highlights produced by the strong morning sun to be rendered correctly (something that is beyond a single exposure). The image still celebrates the building but it also sets itself apart. Unlike architectural photography of the 1920s, the point of view here is offset from the pavilion’s geometry. Moreover, Wall pictures the space as a site of both ‘high’ contemplation and ‘low’ work. The cleaners must arrive and leave before the pavilion opens to the paying public. We see the black carpet is rucked, soap bubbles slide down the glass and the ‘Barcelona Chairs’ – designed by Mies for this building – are shifted out of place. This is a commentary on the legacy of high Modernism. As Wall himself notes:

‘[These] buildings require an especially scrupulous level of maintenance. In more traditional spaces a little dirt and grime is not such a shocking contrast to the whole concept. It can even become patina, but these Miesian buildings resist patina as much as they can.’[xxvi]

Such photographs are complex meditations on all too familiar tension between architectural aspiration and lived experience. They show us idealised spaces populated not by idealised occupants or affluent consumers but by those who often remain invisible. Somehow, somewhere along the line, powerful architecture lost sight of the democratic goals of its modern citizenry. Far too often we find ourselves at odds, or in deadlock, with the built world around us.

Pasts and futures

If we accept that the experience of architecture may now be inseparable from the experience of its imagery, and that photography may now belong to the very same networks of spectacle, it becomes clear that an independent and critical photography of architecture is as vital as it is endangered. My essay thus far has attempted to track something of this critical spirit from its origins in the 1920s. I end with an example that might point us toward future possibilities.

In 2009 the Swiss artist Jules Spinatsch photographed the annual Ball at the Vienna Opera House (the Wiener Staatsoper). Completed in 1869, the style of the building is typically neo-Renaissance, but its form is an idealised expression of mid-nineteenth century spectacle and power. By that time, opera had become an integral part of the social calendar for Europe’s high society and political elites. The plan optimises the number of boxes viewable from each box and from the seats in the stalls. Since 1935 the annual Opera Ball has had an international standing as a rather smug and self-congratulatory dressing-up party for the day’s dubious mix of politicians, businessmen, debutantes and imported celebrities. In the long and luxurious evening, attendees prop up their reputations and grease the wheels of power with an appeal to ‘tradition’. Since the 1960s, the ball has been picketed by various groups objecting to its outdated values. Inside there is barely any need for a performance: all the seats in the stalls are covered over by a ballroom floor, while tiers of extra boxes are erected on the stage to complete the narcissistic, self-gazing circle. In 2009 Spinatsch suspended two interactive network digital cameras in the centre of the Opera House. They were programmed to track incrementally, taking in the entire space, ceiling to floor. One image was recorded every three seconds between the start of the Ball at 8.32pm and its conclusion at 5.17am: 10,008 photographs in total. While doing so, the cameras together completed two full rotations, so every spot in the opera house was covered exactly twice during the evening.

Jules Spinatsch, Installation view of the circular panorama Vienna MMIX – 10008/7000 , Karlsplatz, Vienna, 2011

In 2011 Spinatsch installed his results as a 360° panorama in Vienna’s Resselpark, Karlsplatz. The images were arranged as a chronological grid, the beginning of the evening wrapping around to meet its end. However, instead of placing the spectator at the centre surrounded by the view, Spinatsch put the panorama on the outside, inverting the space of the Opera House to allow viewers to encircle it. The socially exclusive interior is exposed to a democratic exterior. Subversively then, the cavorting elite is put on display for all of Vienna’s citizens to see.

While we ought not overestimate the radicality or ‘impact’ of Spinatsch’s gesture, his rethinking of the twin spectacles of architecture and hi-tech imagery is welcome. And if architecture and photography are destined to remain intertwined then we are obliged ask what it is we want from both.

[i] Walter Benjamin, ‘A Little History of Photography’ (1931), Selected Writings: 1931 – 1934, translated by Rodney Livingstone and others, edited by Michael W Jennings (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005, p523)

[ii] See for example Beatriz Colomina, Privacy and Publicity: Modern Architecture As Mass Media (MIT Press, 1996)

[iii] Sir John Robison, ‘Perfection of the Art, as stated in Notes on Daguerre’s Photography’( The American Journal of Science and Arts , Vol. 37, No. 1, July 1839, pp 183-185)

[iv] As Denis Hollier put it, ‘Like the mutilated classical statue, a photograph seems to result from the art work’s encounter with a scythe of real time, showing the bruise imprinted upon an art work by a clash with a time not its own.’ See Denis Hollier, ‘Beyond Collage: Reflections on the André Malraux of L’Espoir and of Le Musée Imaginaire ’ ( Art Press , no. 221, 1997.

[v] Edward Weston, entry for 10 March 1924, in The Daybooks of Edward Weston (Aperture, 1973) quoted in Nancy Newhall ed., Edward Weston: the flame of Recognition (Gordon Fraser, 1975, p12.

[vi] László Moholy-Nagy, ‘The Future of the Photographic Process’ ( Malerei, Fotografie, Film , 1925), reprinted in English (MIT Press, 1969, p 33)

[vii] Pierre Mac Orlan, Preface to Atget: Photographe de Paris (E Weyhe, 1930). In an article on contemporary photography from 1932, Marcel Fautrad declared: ‘Life … is profoundly marked by Metal. METAL. METAL. Cold contact that bristles. And yet “an aesthetic is born of the surrounding need for metal”’. See Marcel Fautrad ‘The Poetics of Metal’ (June 1932), reprinted in Janus ed., Man Ray: the Photographic Image (Gordon Fraser, 1977, p 219)

[viii] See Atget: Photographe de Paris (E Weyhe, 1930); and Berenice Abbott, The World of Atget (Horizon Press, 1964)

[ix] Walker Evans: Photographs of Nineteenth-Century Houses , Museum of Modern Art, New York, 16 November – 8 December 1933

[x] Clement Greenberg suggested that Evans’ best pictures had ‘backs’ i.e. no receding perspectival space. See Clement Greenberg, ‘The Camera’s Glass Eye: Review of an Exhibition of Edward Weston’ (1946) in Clement Greenberg, The Collected Essays and Criticism , Vol. 2: Arrogant Purpose , 1945–49 , ed. John O’Brian, (University of Chicago Press, 1986, pp 60-63). Jean-François Chevrier has called this kind of photograph an ‘image-sign, a document-monument’, and it recurs throughout Evans’ work. Jean-François Chevrier ‘Dual Reading’ in Jean-François Chevrier, Allan Sekula and Benjamin HD Buchloh eds., Walker Evans & Dan Graham (Witte de With, 1992, p19)

[xi] The long list would also include photographers as diverse as Wilhelm Schürmann, Gabriele Basilico, Simon Norfolk and Sze Tsung Leong

[xii] Shore was given a copy of Evans’ American Photographs for his twelfth birthday: ‘It feels much deeper than just an influence. When I saw his work I recognised someone who thought the way I would think if I were mature enough to think that way.’ See ‘Ways of Making Pictures, Stephen Shore in conversation with David Campany’, in Stephen Shore (Fundacio MAPFRE, 2014)

[xiii] Roland Barthes, ‘The New Citroën’ (1956) in Mythologies (1957), (Hill and Wang, 1972). Barthes was prompted to write by the arrival of the streamlined Citroën DS, its curves reminiscent of American designs of the era.

[xiv] See for example Michael Rothenstein, ‘Colour and Modern Architecture, or ‘The Photographic Eye’, ( The Architectural Review , vol. XLIV, May 1946); ‘“Bliss it was in that Dawn to be Alive”: An Interview with John Brandon-Jones’ ( Architectural Design , vol. 10, no. 11, 1979); and Tom Picton, ‘The Craven Image, or The Apotheosis of the Architectural Photograph’ ( The Architects’ Journal , 25 July 1979)

[xv] Stephen Shore, ‘Photography and Architecture’ (1997) in Christy Lange et al, Stephen Shore , (Phaidon Press, 2008)

[xvi] AA Gill, ‘Brutal honesty is always the best policy’ ( The Sunday Times , 2 March 2014)

[xvii] Audio interview with Lewis Baltz: http://www.lacma.org/art/nt-baltz.aspx . The early significance and influence of the New Industrial Parks series was secured through its inclusion the in the influential 1975 exhibition and book New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape (along with the work of Bernhard & Hilla Becher, Frank Gohlke, Henry Wessel, John Schott, Nicholas Nixon and Stephen Shore). See William Jenkins, New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape, International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1975

[xviii] Bernhard and Hilla Becher, Anonyme Skulpturen : Eine Typologie Technischer Bauten (Art Press Verlag, 1970)

[xix] An early article on the Bechers by the minimalist sculptor Carl Andre two years later cemented the arrival of their work as art. See Carl Andre, ‘A Note on Bernhard and Hilla Becher’ ( Artforum vol. 11, no. 4, December 1972)

[xx] Richard Sennett, ‘Recovery: The Photography of Thomas Struth’ in Thomas Struth, Strangers and Friends (Institute of Contemporary Arts, London/Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston/Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, 1994, pp 91-99)

[xxi] It should be said here that there has always been an ‘expressive’ tradition within the photography of architecture. This is Helmut Gernsheim’s little paragraph entitled ‘The Weather’ from his book Focus on Architecture and Sculpture, an original approach to the photography of architecture and sculpture (Fountain Press, 1949): ‘It will be evident from the nature of the work that the weather plays a most important role in the architectural photographer’s life. Generally speaking, outdoor photographs should not be taken on a dull day: only sunlight lends life to form. The photographer may have to wait for days or even weeks until the conditions are as he wants them, but it will repay the trouble. Sometimes I have spent days at a hotel hoping that the sun would break through, and more than once it happened that I returned to London after several days of fruitless waiting, only to find that the very next day was fine and sunny.’

[xxii] Fredric Jameson, ‘Spatial equivalents in the world system’ in Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Duke University Press, 1991, pp 97-129)

[xxiii] The occasion was the festival Istanbul 2010: Cultural Capital of Europe

[xxiv] Previously, Burgin had also made a video project in response to the Barcelona Pavilion

[xxv] ‘Other Criteria: Victor Burgin in conversation with David Campany’ ( Frieze no. 155, April 2013)

[xxvi] Jeff Wall in Craig Burnett, Jeff Wall (Tate, 2005, pp 90-91)

David Campany

Some views of Constructing Worlds: Photography and Architecture in the Modern Age at the Barbican Gallery, London, 2014/2015. Installation photographs by Chris Jackson.

Dezeen Magazine dezeen-logo dezeen-logo

"Infinite" spiralling staircases in Budapest captured in photography by Balint Alovits

Balint Alovits' photography series Time Machine features architectural staircases in Bauhaus and art deco-style buildings in Budapest , Hungary. More

Matt Lambros' After the Final Curtain photographs show America's forgotten movie theatres

In the age of the multiplex cinema , photographer Matt Lambros has scoped out the older, lavishly decorated movie theatres to capture what was left behind after the credits rolled for the last time. More

Matt Van der Velde photographs abandoned insane asylums

Canadian photographer Matt Van der Velde has toured the deserted and decaying hospitals once used to house and treat patients suffering from psychiatric disorders . More

Alastair Philip Wiper photographs the Tulip Pork Luncheon Meat factory

British photographer Alastair Philip Wiper has gone behind the scenes at a Danish factory to reveal the setting where canned pork is produced. More

Barbican residents offer a look inside their homes

Photo essay: photographer Anton Rodriguez has documented the interiors of 22 homes at the iconic Barbican Estate in London. More

Christian Richter's Abandoned series chronicles Europe's empty buildings

Photo essay: German photographer Christian Richter has been breaking into abandoned buildings across Europe to capture their "swan song" for his Abandoned series (+ slideshow). More

Raphael Olivier's photographs of North Korea reveal Pyongyang's unique architecture

Photo essay: now that North Korea is no longer the tourism black spot it once was, French photographer Raphael Olivier has travelled to the notoriously secretive nation's capital to capture its particular architectural style (+ slideshow). More

10 of the best architectural photography series for World Photo Day

It's World Photo Day! To celebrate, we've rounded up 10 of the most popular recent photo essays on Dezeen, including Modernist Palm Springs houses shot by moonlight and Lego models of Brutalist buildings . More

Love Land Stop Time photography series shows Brazil's "tantalising" motels

Photo essay: worried that Brazil 's love motels would fall foul of Olympic development, Dutch duo Vera van de Sandt and Jur Oster visited the pay-by-the-hour rooms to capture the moods of these intimate spaces (+ slideshow). More

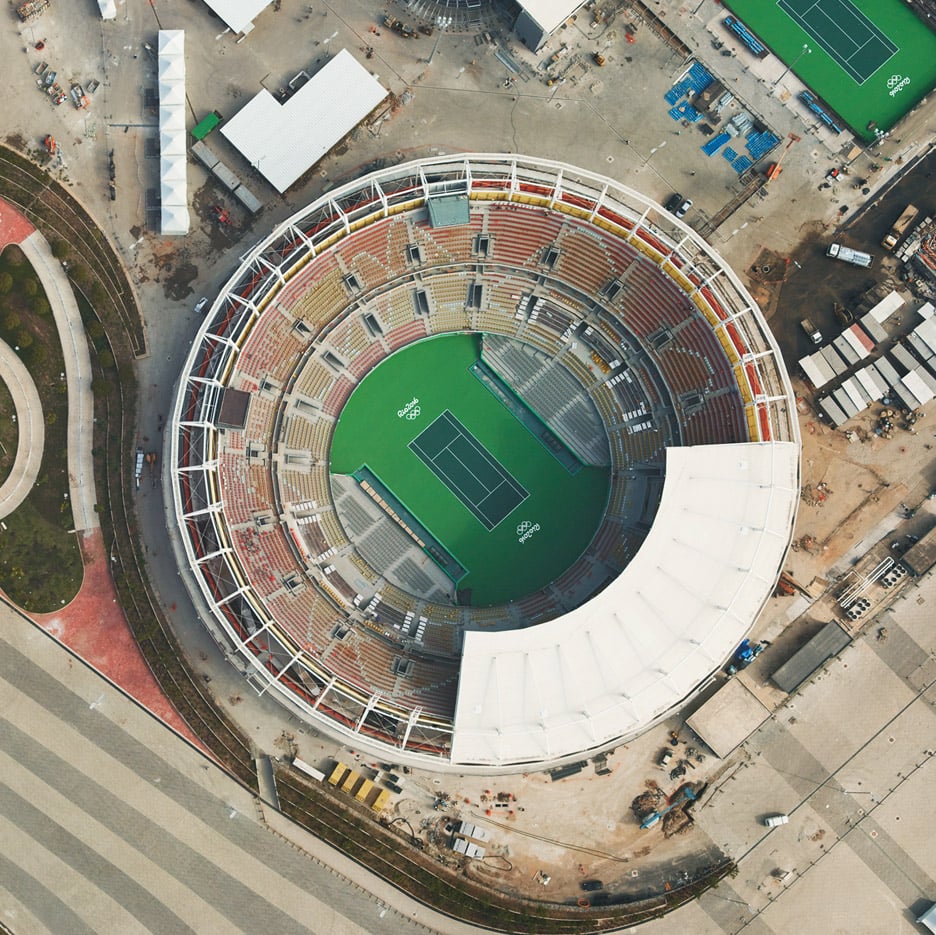

Giles Price's aerial photographs show impact of Olympic venues on Rio

Rio 2016: ahead of this year's Olympic and Paralympic games, British photographer Giles Price took to the skies to capture the physical and social repercussions that stadiums and infrastructure are imposing on Rio de Janeiro (+ slideshow). More

Ward Roberts' photographs capture the colours of sports courts around the world

Photo essay: drawn to the bright hues painted on basketball, tennis and volleyball courts in low-income neighbourhoods, New York-based photographer Ward Roberts has scoured the globe to capture these pastel-toned pockets of urban space (+ slideshow). More

Anthony Gerace's Land's End series chronicles pre-Brexit Cornwall

Photo essay: British photographer Anthony Gerace has produced a series of images offering a snapshot of the crumbling architecture and infrastructure of Cornwall – a stronghold of the Brexit campaign (+ slideshow). More

Mark Havens' Out of Season photographs show Jersey Shore motels "frozen in time"

Photo essay: Philadelphia-based photographer Mark Havens has captured the Modernist architecture and neon signage of motels in a New Jersey resort town, just before many were lost to condominium development (+ slideshow). More

Blueprint for Living: Sharon O'Neill photographs a 60-year-old post-war housing estate

London Festival of Architecture 2016: 60 years after John Leslie Martin completed the Fitzhugh Estate in London, photographer Sharon O'Neill visited to see if the project lived up to its promises (+ slideshow). More

Alicja Dobrucka photographs the seemingly temporary dwellings of a West Bank village

Photo essay: these images by Polish photographer Alicja Dobrucka depict houses disguised as tents in a village in the West Bank (+ slideshow). More

Victor Enrich superimposes New York's Guggenheim onto a troubled Colombian suburb

Photo essay: these images by Spanish photographer and artist Victor Enrich show Frank Lloyd Wright's Guggenheim Museum transported to a Colombian city neighbourhood suffering from an identity crisis (+ slideshow). More

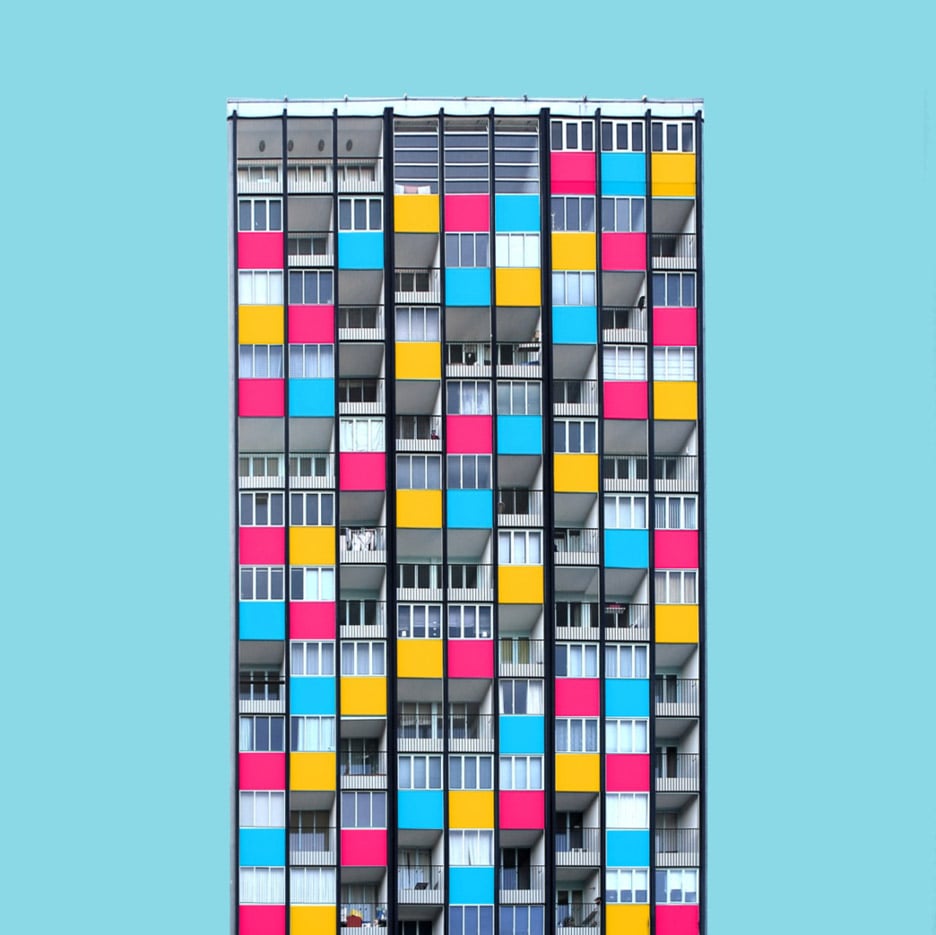

Paul Eis uses Instagram to give German architecture a colourful makeover

Photo essay : keen to embark on career in architecture, young German student Paul Eis has been documenting the buildings of Berlin and Hamburg , but adapting them with bright colours (+ slideshow). More

Scott Benedict captures the raw concrete of the Cité Rateau housing estate in Paris

Photo essay: American photographer Scott Benedict has travelled to the outskirts of Paris to photograph a little-known concrete housing estate, designed by French architects Jean Renaudie and Rénée Gailhoustet (+ slideshow). More

Klaus Pichler goes behind the scenes of Vienna's Natural History Museum

Photo essay: a shark in a corridor and a toad seated on a filing cabinet are among the scenes found by Austrian photographer Klaus Pichler when he went backstage at the Natural History Museum Vienna (+ slideshow). More

Nelson Garrido captures the modern architecture of Kuwait's Golden Era

Photo essay: photographer Nelson Garrido has travelled across Kuwait to document over 150 buildings, revealing the impact of 40 years of social transformation on the Arab state's built environment (+ slideshow). More

- Login / Register

- You are here: Photography

Photo essay: land marks

29 October 2020 By Eleanor Beaumont Photography

Human hands build and break up the Earth; carving cruel lines through the soil they wreak crisis upon our climate, divide here from there and reap profit from the process

Private Land, Brassington, Peak District, 1989, from Fay Godwin’s Our Forbidden Land series, a polemic for the right to roam which Godwin followed up by rallying MPs to trespass on land owned by the Duke of Devonshire

Credit: Album / Alamy

Mongolia 3, by Daesung Lee, 2014

Credit: Daesung Lee

People pock the Earth, marking territory. We build walls, draw lines, dig holes, scorch the ground, simmer the sea. We erase, rip and reassemble in a violent flutter, our traces strewn across the surface. Flimsy fences and small insistent squares forbid entry though the land unfolds open arms. We run blissfully over the edge, over the wall, the point of no return, and continue still, out of control, overwhelmed and fearful.

From Sebastião Salgado’s famous series Gold Mine, Serra Pelada, Brazil, taken in 1986

Credit: Sebastião Salgado / nbpictures.com

Photograph of a promotional fridge magnet depicting diamonds sourced in Yakutia, Russia, displayed as part of Viktor Brim’s installation Imperial Machine, 2020

Credit: Viktor Brim

Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi’s Raia Mutomboki series, 2013, portraying a Belgian tin ore mining building in the South Kivu region of the Congo

Credit: Diana Zeyneb Alhindawi

Under the clawing of thousands of hands, the ground yawns and yields treasure. Human bodies pour into the fissure, become the earth through the critical lens, a seething dark sea. Twenty cents in return for a sack of land hauled from its jaws, gold guarded jealously by fists of rock. The clenched hands open only for a good price: enough to skim the cracks in the crumbling Soviet Union, or to oil the wheels of empire. Despite emancipation from colonial tyranny, the tentacles of European capitalism continue to burrow the land, grasping and suffocating, homes and villages lost in the rubble. Studded with jewels, streaked with metal, the richest lands remain the most impoverished, haunted by imperial ghosts.

Tetrapods #1, Dongying, China, 2016, by Edward Burtynsky

Credit: © Edward Burtynsky, courtesy Flowers Gallery, London / Nicholas Metivier Gallery, Toronto

An aerial view of a burned tract of Amazon jungle as it was cleared by loggers and farmers near Porto Velho, Brazil, 29 August 2019, taken by Ricardo Moraes

Credit: REUTERS / Ricardo Moraes

Beached, 2017, by Leah Dyjak

Credit: Leah Dyjak

The Earth is not earth but a fine smothering concrete skin, fossilising the Anthropocene. The planet burns, seas bubble and overflow, waves snatch hungrily at boiling tarmac. At one edge, the land swirls and eddies; at another, the sea bed is bolstered and armed with lumpen concrete, tossed into the ocean to calm the furious waters. Not to protect human life but to defend fields of oil, to grease the colossal cogs of economy. Land is cleaved by the strong arms of capital; hot lines struck through jungle to clear room for human labour. Trees are worth more dead than alive, and the land they stand on worth even more. But the hands that light the flame and wield the saw are manipulated by forces swilling beyond the bounds of the forest, coursing through the ground like poisonous roots. Land is laid waste in its wake.

Planting of the God TV Forest on the former land of the Bedouin village of al-Araqib, 9 October 2011, from Desert Bloom, part of The Erasure Trilogy by Fazal Sheikh

Credit: Fazal Sheikh

A section of Everest, 2019, a photographic collage by Sohei Nishino, measuring 263 by 150cm

Credit: Sohei Nishino

Napoli 1, 2019, from Sue Barr’s The Architecture of Transit series

Credit: Sue Barr / architectureoftransit.com