Evaluating Research in Academic Journals: A Practical Guide to Realistic Evaluation

- November 2018

- Edition: 7th edition

- Publisher: Routledge (Taylor & Francis)

- ISBN: 978-0815365662

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- University of New Haven

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Victoria Espinoza

- Jesus Alberto Galvan

- Dorothea Ivey

- TOBIAS CHACHA OLAMBO

- DR. MOSES ODHIAMBO ALUOCH (PhD)

- Catherine Briand

- Carol Giba Bottger Garcia

- Kofar Wambai

- J AM COLL HEALTH

- C. Nathan DeWall

- J. Michael Bartels

- Sojung Park

- J APPL DEV PSYCHOL

- Sandra A. Brown

- COMPUT HUM BEHAV

- Alberta Contarello

- Barker Bausell

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Evaluating Research Articles

Understanding research statistics, critical appraisal, help us improve the libguide.

Imagine for a moment that you are trying to answer a clinical (PICO) question regarding one of your patients/clients. Do you know how to determine if a research study is of high quality? Can you tell if it is applicable to your question? In evidence based practice, there are many things to look for in an article that will reveal its quality and relevance. This guide is a collection of resources and activities that will help you learn how to evaluate articles efficiently and accurately.

Is health research new to you? Or perhaps you're a little out of practice with reading it? The following questions will help illuminate an article's strengths or shortcomings. Ask them of yourself as you are reading an article:

- Is the article peer reviewed?

- Are there any conflicts of interest based on the author's affiliation or the funding source of the research?

- Are the research questions or objectives clearly defined?

- Is the study a systematic review or meta analysis?

- Is the study design appropriate for the research question?

- Is the sample size justified? Do the authors explain how it is representative of the wider population?

- Do the researchers describe the setting of data collection?

- Does the paper clearly describe the measurements used?

- Did the researchers use appropriate statistical measures?

- Are the research questions or objectives answered?

- Did the researchers account for confounding factors?

- Have the researchers only drawn conclusions about the groups represented in the research?

- Have the authors declared any conflicts of interest?

If the answer to these questions about an article you are reading are mostly YESes , then it's likely that the article is of decent quality. If the answers are most NOs , then it may be a good idea to move on to another article. If the YESes and NOs are roughly even, you'll have to decide for yourself if the article is good enough quality for you. Some factors, like a poor literature review, are not as important as the researchers neglecting to describe the measurements they used. As you read more research, you'll be able to more easily identify research that is well done vs. that which is not well done.

Determining if a research study has used appropriate statistical measures is one of the most critical and difficult steps in evaluating an article. The following links are great, quick resources for helping to better understand how to use statistics in health research.

- How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls This article continues the checklist of questions that will help you to appraise the statistical validity of a paper. Greenhalgh Trisha. How to read a paper: Statistics for the non-statistician. II: “Significant” relations and their pitfalls BMJ 1997; 315 :422 *On the PMC PDF, you need to scroll past the first article to get to this one.*

- A consumer's guide to subgroup analysis The extent to which a clinician should believe and act on the results of subgroup analyses of data from randomized trials or meta-analyses is controversial. Guidelines are provided in this paper for making these decisions.

Statistical Versus Clinical Significance

When appraising studies, it's important to consider both the clinical and statistical significance of the research. This video offers a quick explanation of why.

If you have a little more time, this video explores statistical and clinical significance in more detail, including examples of how to calculate an effect size.

- Statistical vs. Clinical Significance Transcript Transcript document for the Statistical vs. Clinical Significance video.

- Effect Size Transcript Transcript document for the Effect Size video.

- P Values, Statistical Significance & Clinical Significance This handout also explains clinical and statistical significance.

- Absolute versus relative risk – making sense of media stories Understanding the difference between relative and absolute risk is essential to understanding statistical tests commonly found in research articles.

Critical appraisal is the process of systematically evaluating research using established and transparent methods. In critical appraisal, health professionals use validated checklists/worksheets as tools to guide their assessment of the research. It is a more advanced way of evaluating research than the more basic method explained above. To learn more about critical appraisal or to access critical appraisal tools, visit the websites below.

- Last Updated: Jun 11, 2024 10:26 AM

- URL: https://libguides.massgeneral.org/evaluatingarticles

Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 September 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 679–689, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Drishti Yadav ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2974-0323 1

98k Accesses

45 Citations

71 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This review aims to synthesize a published set of evaluative criteria for good qualitative research. The aim is to shed light on existing standards for assessing the rigor of qualitative research encompassing a range of epistemological and ontological standpoints. Using a systematic search strategy, published journal articles that deliberate criteria for rigorous research were identified. Then, references of relevant articles were surveyed to find noteworthy, distinct, and well-defined pointers to good qualitative research. This review presents an investigative assessment of the pivotal features in qualitative research that can permit the readers to pass judgment on its quality and to condemn it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the necessity to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. It also offers some prospects and recommendations to improve the quality of qualitative research. Based on the findings of this review, it is concluded that quality criteria are the aftereffect of socio-institutional procedures and existing paradigmatic conducts. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single and specific set of quality criteria is neither feasible nor anticipated. Since qualitative research is not a cohesive discipline, researchers need to educate and familiarize themselves with applicable norms and decisive factors to evaluate qualitative research from within its theoretical and methodological framework of origin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Good Qualitative Research: Opening up the Debate

Beyond qualitative/quantitative structuralism: the positivist qualitative research and the paradigmatic disclaimer.

What is Qualitative in Research

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“… It is important to regularly dialogue about what makes for good qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 , p. 837)

To decide what represents good qualitative research is highly debatable. There are numerous methods that are contained within qualitative research and that are established on diverse philosophical perspectives. Bryman et al., ( 2008 , p. 262) suggest that “It is widely assumed that whereas quality criteria for quantitative research are well‐known and widely agreed, this is not the case for qualitative research.” Hence, the question “how to evaluate the quality of qualitative research” has been continuously debated. There are many areas of science and technology wherein these debates on the assessment of qualitative research have taken place. Examples include various areas of psychology: general psychology (Madill et al., 2000 ); counseling psychology (Morrow, 2005 ); and clinical psychology (Barker & Pistrang, 2005 ), and other disciplines of social sciences: social policy (Bryman et al., 2008 ); health research (Sparkes, 2001 ); business and management research (Johnson et al., 2006 ); information systems (Klein & Myers, 1999 ); and environmental studies (Reid & Gough, 2000 ). In the literature, these debates are enthused by the impression that the blanket application of criteria for good qualitative research developed around the positivist paradigm is improper. Such debates are based on the wide range of philosophical backgrounds within which qualitative research is conducted (e.g., Sandberg, 2000 ; Schwandt, 1996 ). The existence of methodological diversity led to the formulation of different sets of criteria applicable to qualitative research.

Among qualitative researchers, the dilemma of governing the measures to assess the quality of research is not a new phenomenon, especially when the virtuous triad of objectivity, reliability, and validity (Spencer et al., 2004 ) are not adequate. Occasionally, the criteria of quantitative research are used to evaluate qualitative research (Cohen & Crabtree, 2008 ; Lather, 2004 ). Indeed, Howe ( 2004 ) claims that the prevailing paradigm in educational research is scientifically based experimental research. Hypotheses and conjectures about the preeminence of quantitative research can weaken the worth and usefulness of qualitative research by neglecting the prominence of harmonizing match for purpose on research paradigm, the epistemological stance of the researcher, and the choice of methodology. Researchers have been reprimanded concerning this in “paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences” (Lincoln & Guba, 2000 ).

In general, qualitative research tends to come from a very different paradigmatic stance and intrinsically demands distinctive and out-of-the-ordinary criteria for evaluating good research and varieties of research contributions that can be made. This review attempts to present a series of evaluative criteria for qualitative researchers, arguing that their choice of criteria needs to be compatible with the unique nature of the research in question (its methodology, aims, and assumptions). This review aims to assist researchers in identifying some of the indispensable features or markers of high-quality qualitative research. In a nutshell, the purpose of this systematic literature review is to analyze the existing knowledge on high-quality qualitative research and to verify the existence of research studies dealing with the critical assessment of qualitative research based on the concept of diverse paradigmatic stances. Contrary to the existing reviews, this review also suggests some critical directions to follow to improve the quality of qualitative research in different epistemological and ontological perspectives. This review is also intended to provide guidelines for the acceleration of future developments and dialogues among qualitative researchers in the context of assessing the qualitative research.

The rest of this review article is structured in the following fashion: Sect. Methods describes the method followed for performing this review. Section Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies provides a comprehensive description of the criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. This section is followed by a summary of the strategies to improve the quality of qualitative research in Sect. Improving Quality: Strategies . Section How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings? provides details on how to assess the quality of the research findings. After that, some of the quality checklists (as tools to evaluate quality) are discussed in Sect. Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality . At last, the review ends with the concluding remarks presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook . Some prospects in qualitative research for enhancing its quality and usefulness in the social and techno-scientific research community are also presented in Sect. Conclusions, Future Directions and Outlook .

For this review, a comprehensive literature search was performed from many databases using generic search terms such as Qualitative Research , Criteria , etc . The following databases were chosen for the literature search based on the high number of results: IEEE Explore, ScienceDirect, PubMed, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. The following keywords (and their combinations using Boolean connectives OR/AND) were adopted for the literature search: qualitative research, criteria, quality, assessment, and validity. The synonyms for these keywords were collected and arranged in a logical structure (see Table 1 ). All publications in journals and conference proceedings later than 1950 till 2021 were considered for the search. Other articles extracted from the references of the papers identified in the electronic search were also included. A large number of publications on qualitative research were retrieved during the initial screening. Hence, to include the searches with the main focus on criteria for good qualitative research, an inclusion criterion was utilized in the search string.

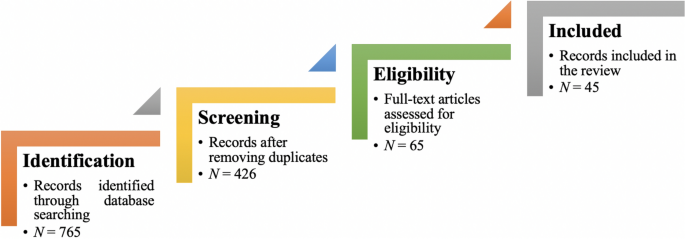

From the selected databases, the search retrieved a total of 765 publications. Then, the duplicate records were removed. After that, based on the title and abstract, the remaining 426 publications were screened for their relevance by using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 2 ). Publications focusing on evaluation criteria for good qualitative research were included, whereas those works which delivered theoretical concepts on qualitative research were excluded. Based on the screening and eligibility, 45 research articles were identified that offered explicit criteria for evaluating the quality of qualitative research and were found to be relevant to this review.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete review process in the form of PRISMA flow diagram. PRISMA, i.e., “preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses” is employed in systematic reviews to refine the quality of reporting.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the search and inclusion process. N represents the number of records

Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Studies

Fundamental criteria: general research quality.

Various researchers have put forward criteria for evaluating qualitative research, which have been summarized in Table 3 . Also, the criteria outlined in Table 4 effectively deliver the various approaches to evaluate and assess the quality of qualitative work. The entries in Table 4 are based on Tracy’s “Eight big‐tent criteria for excellent qualitative research” (Tracy, 2010 ). Tracy argues that high-quality qualitative work should formulate criteria focusing on the worthiness, relevance, timeliness, significance, morality, and practicality of the research topic, and the ethical stance of the research itself. Researchers have also suggested a series of questions as guiding principles to assess the quality of a qualitative study (Mays & Pope, 2020 ). Nassaji ( 2020 ) argues that good qualitative research should be robust, well informed, and thoroughly documented.

Qualitative Research: Interpretive Paradigms

All qualitative researchers follow highly abstract principles which bring together beliefs about ontology, epistemology, and methodology. These beliefs govern how the researcher perceives and acts. The net, which encompasses the researcher’s epistemological, ontological, and methodological premises, is referred to as a paradigm, or an interpretive structure, a “Basic set of beliefs that guides action” (Guba, 1990 ). Four major interpretive paradigms structure the qualitative research: positivist and postpositivist, constructivist interpretive, critical (Marxist, emancipatory), and feminist poststructural. The complexity of these four abstract paradigms increases at the level of concrete, specific interpretive communities. Table 5 presents these paradigms and their assumptions, including their criteria for evaluating research, and the typical form that an interpretive or theoretical statement assumes in each paradigm. Moreover, for evaluating qualitative research, quantitative conceptualizations of reliability and validity are proven to be incompatible (Horsburgh, 2003 ). In addition, a series of questions have been put forward in the literature to assist a reviewer (who is proficient in qualitative methods) for meticulous assessment and endorsement of qualitative research (Morse, 2003 ). Hammersley ( 2007 ) also suggests that guiding principles for qualitative research are advantageous, but methodological pluralism should not be simply acknowledged for all qualitative approaches. Seale ( 1999 ) also points out the significance of methodological cognizance in research studies.

Table 5 reflects that criteria for assessing the quality of qualitative research are the aftermath of socio-institutional practices and existing paradigmatic standpoints. Owing to the paradigmatic diversity of qualitative research, a single set of quality criteria is neither possible nor desirable. Hence, the researchers must be reflexive about the criteria they use in the various roles they play within their research community.

Improving Quality: Strategies

Another critical question is “How can the qualitative researchers ensure that the abovementioned quality criteria can be met?” Lincoln and Guba ( 1986 ) delineated several strategies to intensify each criteria of trustworthiness. Other researchers (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016 ; Shenton, 2004 ) also presented such strategies. A brief description of these strategies is shown in Table 6 .

It is worth mentioning that generalizability is also an integral part of qualitative research (Hays & McKibben, 2021 ). In general, the guiding principle pertaining to generalizability speaks about inducing and comprehending knowledge to synthesize interpretive components of an underlying context. Table 7 summarizes the main metasynthesis steps required to ascertain generalizability in qualitative research.

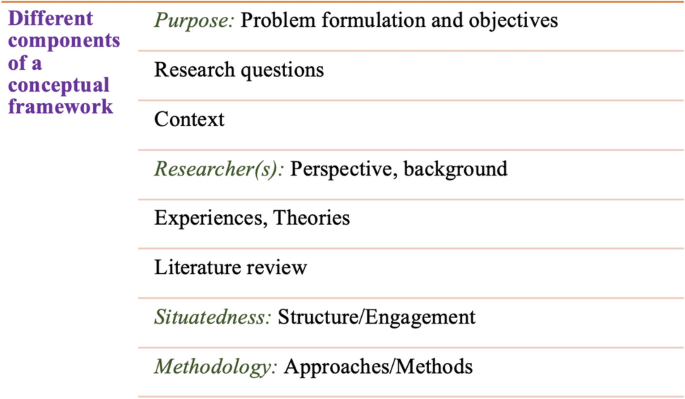

Figure 2 reflects the crucial components of a conceptual framework and their contribution to decisions regarding research design, implementation, and applications of results to future thinking, study, and practice (Johnson et al., 2020 ). The synergy and interrelationship of these components signifies their role to different stances of a qualitative research study.

Essential elements of a conceptual framework

In a nutshell, to assess the rationale of a study, its conceptual framework and research question(s), quality criteria must take account of the following: lucid context for the problem statement in the introduction; well-articulated research problems and questions; precise conceptual framework; distinct research purpose; and clear presentation and investigation of the paradigms. These criteria would expedite the quality of qualitative research.

How to Assess the Quality of the Research Findings?

The inclusion of quotes or similar research data enhances the confirmability in the write-up of the findings. The use of expressions (for instance, “80% of all respondents agreed that” or “only one of the interviewees mentioned that”) may also quantify qualitative findings (Stenfors et al., 2020 ). On the other hand, the persuasive reason for “why this may not help in intensifying the research” has also been provided (Monrouxe & Rees, 2020 ). Further, the Discussion and Conclusion sections of an article also prove robust markers of high-quality qualitative research, as elucidated in Table 8 .

Quality Checklists: Tools for Assessing the Quality

Numerous checklists are available to speed up the assessment of the quality of qualitative research. However, if used uncritically and recklessly concerning the research context, these checklists may be counterproductive. I recommend that such lists and guiding principles may assist in pinpointing the markers of high-quality qualitative research. However, considering enormous variations in the authors’ theoretical and philosophical contexts, I would emphasize that high dependability on such checklists may say little about whether the findings can be applied in your setting. A combination of such checklists might be appropriate for novice researchers. Some of these checklists are listed below:

The most commonly used framework is Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) (Tong et al., 2007 ). This framework is recommended by some journals to be followed by the authors during article submission.

Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is another checklist that has been created particularly for medical education (O’Brien et al., 2014 ).

Also, Tracy ( 2010 ) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP, 2021 ) offer criteria for qualitative research relevant across methods and approaches.

Further, researchers have also outlined different criteria as hallmarks of high-quality qualitative research. For instance, the “Road Trip Checklist” (Epp & Otnes, 2021 ) provides a quick reference to specific questions to address different elements of high-quality qualitative research.

Conclusions, Future Directions, and Outlook

This work presents a broad review of the criteria for good qualitative research. In addition, this article presents an exploratory analysis of the essential elements in qualitative research that can enable the readers of qualitative work to judge it as good research when objectively and adequately utilized. In this review, some of the essential markers that indicate high-quality qualitative research have been highlighted. I scope them narrowly to achieve rigor in qualitative research and note that they do not completely cover the broader considerations necessary for high-quality research. This review points out that a universal and versatile one-size-fits-all guideline for evaluating the quality of qualitative research does not exist. In other words, this review also emphasizes the non-existence of a set of common guidelines among qualitative researchers. In unison, this review reinforces that each qualitative approach should be treated uniquely on account of its own distinctive features for different epistemological and disciplinary positions. Owing to the sensitivity of the worth of qualitative research towards the specific context and the type of paradigmatic stance, researchers should themselves analyze what approaches can be and must be tailored to ensemble the distinct characteristics of the phenomenon under investigation. Although this article does not assert to put forward a magic bullet and to provide a one-stop solution for dealing with dilemmas about how, why, or whether to evaluate the “goodness” of qualitative research, it offers a platform to assist the researchers in improving their qualitative studies. This work provides an assembly of concerns to reflect on, a series of questions to ask, and multiple sets of criteria to look at, when attempting to determine the quality of qualitative research. Overall, this review underlines the crux of qualitative research and accentuates the need to evaluate such research by the very tenets of its being. Bringing together the vital arguments and delineating the requirements that good qualitative research should satisfy, this review strives to equip the researchers as well as reviewers to make well-versed judgment about the worth and significance of the qualitative research under scrutiny. In a nutshell, a comprehensive portrayal of the research process (from the context of research to the research objectives, research questions and design, speculative foundations, and from approaches of collecting data to analyzing the results, to deriving inferences) frequently proliferates the quality of a qualitative research.

Prospects : A Road Ahead for Qualitative Research

Irrefutably, qualitative research is a vivacious and evolving discipline wherein different epistemological and disciplinary positions have their own characteristics and importance. In addition, not surprisingly, owing to the sprouting and varied features of qualitative research, no consensus has been pulled off till date. Researchers have reflected various concerns and proposed several recommendations for editors and reviewers on conducting reviews of critical qualitative research (Levitt et al., 2021 ; McGinley et al., 2021 ). Following are some prospects and a few recommendations put forward towards the maturation of qualitative research and its quality evaluation:

In general, most of the manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts. Hence, it is more likely that they would prefer to adopt a broad set of criteria. However, researchers and reviewers need to keep in mind that it is inappropriate to utilize the same approaches and conducts among all qualitative research. Therefore, future work needs to focus on educating researchers and reviewers about the criteria to evaluate qualitative research from within the suitable theoretical and methodological context.

There is an urgent need to refurbish and augment critical assessment of some well-known and widely accepted tools (including checklists such as COREQ, SRQR) to interrogate their applicability on different aspects (along with their epistemological ramifications).

Efforts should be made towards creating more space for creativity, experimentation, and a dialogue between the diverse traditions of qualitative research. This would potentially help to avoid the enforcement of one's own set of quality criteria on the work carried out by others.

Moreover, journal reviewers need to be aware of various methodological practices and philosophical debates.

It is pivotal to highlight the expressions and considerations of qualitative researchers and bring them into a more open and transparent dialogue about assessing qualitative research in techno-scientific, academic, sociocultural, and political rooms.

Frequent debates on the use of evaluative criteria are required to solve some potentially resolved issues (including the applicability of a single set of criteria in multi-disciplinary aspects). Such debates would not only benefit the group of qualitative researchers themselves, but primarily assist in augmenting the well-being and vivacity of the entire discipline.

To conclude, I speculate that the criteria, and my perspective, may transfer to other methods, approaches, and contexts. I hope that they spark dialog and debate – about criteria for excellent qualitative research and the underpinnings of the discipline more broadly – and, therefore, help improve the quality of a qualitative study. Further, I anticipate that this review will assist the researchers to contemplate on the quality of their own research, to substantiate research design and help the reviewers to review qualitative research for journals. On a final note, I pinpoint the need to formulate a framework (encompassing the prerequisites of a qualitative study) by the cohesive efforts of qualitative researchers of different disciplines with different theoretic-paradigmatic origins. I believe that tailoring such a framework (of guiding principles) paves the way for qualitative researchers to consolidate the status of qualitative research in the wide-ranging open science debate. Dialogue on this issue across different approaches is crucial for the impending prospects of socio-techno-educational research.

Amin, M. E. K., Nørgaard, L. S., Cavaco, A. M., Witry, M. J., Hillman, L., Cernasev, A., & Desselle, S. P. (2020). Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 16 (10), 1472–1482.

Article Google Scholar

Barker, C., & Pistrang, N. (2005). Quality criteria under methodological pluralism: Implications for conducting and evaluating research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35 (3–4), 201–212.

Bryman, A., Becker, S., & Sempik, J. (2008). Quality criteria for quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research: A view from social policy. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11 (4), 261–276.

Caelli, K., Ray, L., & Mill, J. (2003). ‘Clear as mud’: Toward greater clarity in generic qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 2 (2), 1–13.

CASP (2021). CASP checklists. Retrieved May 2021 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Cohen, D. J., & Crabtree, B. F. (2008). Evaluative criteria for qualitative research in health care: Controversies and recommendations. The Annals of Family Medicine, 6 (4), 331–339.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The sage handbook of qualitative research (pp. 1–32). Sage Publications Ltd.

Google Scholar

Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38 (3), 215–229.

Epp, A. M., & Otnes, C. C. (2021). High-quality qualitative research: Getting into gear. Journal of Service Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670520961445

Guba, E. G. (1990). The paradigm dialog. In Alternative paradigms conference, mar, 1989, Indiana u, school of education, San Francisco, ca, us . Sage Publications, Inc.

Hammersley, M. (2007). The issue of quality in qualitative research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 30 (3), 287–305.

Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A Delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406920976417.

Hays, D. G., & McKibben, W. B. (2021). Promoting rigorous research: Generalizability and qualitative research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 99 (2), 178–188.

Horsburgh, D. (2003). Evaluation of qualitative research. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12 (2), 307–312.

Howe, K. R. (2004). A critique of experimentalism. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 42–46.

Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84 (1), 7120.

Johnson, P., Buehring, A., Cassell, C., & Symon, G. (2006). Evaluating qualitative management research: Towards a contingent criteriology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 8 (3), 131–156.

Klein, H. K., & Myers, M. D. (1999). A set of principles for conducting and evaluating interpretive field studies in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 23 (1), 67–93.

Lather, P. (2004). This is your father’s paradigm: Government intrusion and the case of qualitative research in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 10 (1), 15–34.

Levitt, H. M., Morrill, Z., Collins, K. M., & Rizo, J. L. (2021). The methodological integrity of critical qualitative research: Principles to support design and research review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68 (3), 357.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1986). But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation, 1986 (30), 73–84.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 163–188). Sage Publications.

Madill, A., Jordan, A., & Shirley, C. (2000). Objectivity and reliability in qualitative analysis: Realist, contextualist and radical constructionist epistemologies. British Journal of Psychology, 91 (1), 1–20.

Mays, N., & Pope, C. (2020). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Research in Health Care . https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119410867.ch15

McGinley, S., Wei, W., Zhang, L., & Zheng, Y. (2021). The state of qualitative research in hospitality: A 5-year review 2014 to 2019. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 62 (1), 8–20.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, US.

Meyer, M., & Dykes, J. (2019). Criteria for rigor in visualization design study. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics, 26 (1), 87–97.

Monrouxe, L. V., & Rees, C. E. (2020). When I say… quantification in qualitative research. Medical Education, 54 (3), 186–187.

Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52 (2), 250.

Morse, J. M. (2003). A review committee’s guide for evaluating qualitative proposals. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (6), 833–851.

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24 (4), 427–431.

O’Brien, B. C., Harris, I. B., Beckman, T. J., Reed, D. A., & Cook, D. A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89 (9), 1245–1251.

O’Connor, C., & Joffe, H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19 , 1609406919899220.

Reid, A., & Gough, S. (2000). Guidelines for reporting and evaluating qualitative research: What are the alternatives? Environmental Education Research, 6 (1), 59–91.

Rocco, T. S. (2010). Criteria for evaluating qualitative studies. Human Resource Development International . https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2010.501959

Sandberg, J. (2000). Understanding human competence at work: An interpretative approach. Academy of Management Journal, 43 (1), 9–25.

Schwandt, T. A. (1996). Farewell to criteriology. Qualitative Inquiry, 2 (1), 58–72.

Seale, C. (1999). Quality in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 5 (4), 465–478.

Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22 (2), 63–75.

Sparkes, A. C. (2001). Myth 94: Qualitative health researchers will agree about validity. Qualitative Health Research, 11 (4), 538–552.

Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2004). Quality in qualitative evaluation: A framework for assessing research evidence.

Stenfors, T., Kajamaa, A., & Bennett, D. (2020). How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher, 17 (6), 596–599.

Taylor, E. W., Beck, J., & Ainsworth, E. (2001). Publishing qualitative adult education research: A peer review perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 33 (2), 163–179.

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19 (6), 349–357.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16 (10), 837–851.

Download references

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Informatics, Technische Universität Wien, 1040, Vienna, Austria

Drishti Yadav

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Drishti Yadav .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Yadav, D. Criteria for Good Qualitative Research: A Comprehensive Review. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 31 , 679–689 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Download citation

Accepted : 28 August 2021

Published : 18 September 2021

Issue Date : December 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-021-00619-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Qualitative research

- Evaluative criteria

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 March 2021

Research impact evaluation and academic discourse

- Marta Natalia Wróblewska ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8575-5215 1 , 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 58 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

5582 Accesses

13 Citations

40 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Language and linguistics

- Science, technology and society

The introduction of ‘impact’ as an element of assessment constitutes a major change in the construction of research evaluation systems. While various protocols of impact evaluation exist, the most articulated one was implemented as part of the British Research Excellence Framework (REF). This paper investigates the nature and consequences of the rise of ‘research impact’ as an element of academic evaluation from the perspective of discourse. Drawing from linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian discourse analysis, the study discusses shifts related to the so-called Impact Agenda on four stages, in chronological order: (1) the ‘problematization’ of the notion of ‘impact’, (2) the establishment of an ‘impact infrastructure’, (3) the consolidation of a new genre of writing–impact case study, and (4) academics’ positioning practices towards the notion of ‘impact’, theorized here as the triggering of new practices of ‘subjectivation’ of the academic self. The description of the basic functioning of the ‘discourse of impact’ is based on the analysis of two corpora: case studies submitted by a selected group of academics (linguists) to REF2014 (no = 78) and interviews ( n = 25) with their authors. Linguistic pragmatics is particularly useful in analyzing linguistic aspects of the data, while Foucault’s theory helps draw together findings from two datasets in a broader analysis based on a governmentality framework. This approach allows for more general conclusions on the practices of governing (academic) subjects within evaluation contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Writing impact case studies: a comparative study of high-scoring and low-scoring case studies from REF2014

The transformative power of values-enacted scholarship

IDADA: towards a multimethod methodological framework for PhD by publication underpinned by critical realism

Introduction.

The introduction of ‘research impact’ as an element of evaluation constitutes a major change in the construction of research evaluation systems. ‘Impact’, understood broadly as the influence of academic research beyond the academic sphere, including areas such as business, education, public health, policy, public debate, culture etc., has been progressively implemented in various systems of science evaluation—a trend observable worldwide (Donovan, 2011 ; Grant et al., 2009 ; European Science Foundation, 2012 ). Salient examples of attempts to systematically evaluate research impact include the Australian Research Quality Framework–RQF (Donovan, 2008 ) and the Dutch Standard Evaluation Protocol (VSNU–Association of Universities in the Netherlands, 2016 , see ‘societal relevance’).

The most articulated system of impact evaluation to date was implemented in the British cyclical ex post assessment of academic units, Research Excellence Framework (REF), as part of a broader governmental policy—the Impact Agenda. REF is the most-studied and probably the most influential impact evaluation system to date. It has been used as a model for analogous evaluations in other countries. These include the Norwegian Humeval exercise for the humanities (Research Council of Norway, 2017 , pp. 36–37, Wróblewska, 2019 ) and ensuing evaluations of other fields (Research Council of Norway, 2018 , pp. 32–34; Wróblewska, 2019 , pp. 12–16). REF has also directly inspired impact evaluation protocols in Hong-Kong (Hong Kong University Grants Committee, 2018 ) and Poland (Wróblewska, 2017 ). This study is based on data collected in the context of the British REF2014 but it advances a description of the ‘discourse of impact’ that can be generalized and applied to other national and international contexts.

Although impact evaluation is a new practice, a body of literature has been produced on the topic. This includes policy documents on the first edition of REF in 2014 (HEFCE, 2015 ; Stern, 2016 ) and related reports, be it commissioned (King’s College London and Digital Science, 2015 ; Manville et al., 2014 , 2015 ) or conducted independently (National co-ordinating center for public engagement, 2014 ). There also exists a scholarly literature which reflects on the theoretical underpinnings of impact evaluations (Gunn and Mintrom, 2016 , 2018 ; Watermeyer, 2012 , 2016 ) and the observable consequences of the exercise for academic practice (Chubb and Watermeyer, 2017 ; Chubb et al., 2016 ; Watermeyer, 2014 ). While these reports and studies mainly draw on the methods of philosophy, sociology and management, many of them also allude to changes related to language .

Several publications on impact drew attention to the process of meaning-making around the notion of ‘impact’ in the early stages of its existence. Manville et al. flagged up the necessity for the policy-maker to facilitate the development of common vocabulary to enable a broader ‘cultural shift’ (2015, pp. 16, 26. 37–38, 69). Power wrote of an emerging ‘performance discourse of impact’ (2015, p. 44) while Derrick ( 2018 ) looked at the collective process of defining and delimiting “the ambiguous object” of impact at the stage of panel proceedings. The present paper picks up these observations bringing them together in a unique discursive perspective.

Drawing from linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian discourse analysis, the paper presents shifts related to the introduction of ‘impact’ as element of evaluation in four stages. These are, in chronological order: (1) the ‘problematisation’ of the notion of ‘impact’ in policy and its appropriation on a local level, (2) the creation of an impact infrastructure to orchestrate practices around impact, (3) the consolidation of a new genre of writing—impact case study, (4) academics’ uptake of the notion of impact and its progressive inclusion in their professional positioning.

Each of these stages is described using theoretical concepts grounded in empirical data. The first stage has to do with the process of ‘problematization’ of a previously non-regulated area, i.e., the process of casting research impact as a ‘problem’ to be addressed and regulated by a set of policy measures. The second stage took place when in rapid response to government policy, new procedures and practices were created within universities, giving rise to an impact ‘infrastructure’ (or ‘apparatus’ in the Foucauldian sense). The third stage is the emergence of a crucial element of the infrastructure—a new genre of academic writing—impact case study. I argue that engaging with the new genre and learning to write impact case studies was key in incorporating ‘impact’ into scholars’ narratives of ‘academic identity’. Hence, the paper presents new practices of ‘subjectivation’ as the fourth stage of incorporation of ‘impact’ into academic discourse. The four stages of the introduction of ‘impact’ into academic discourse are mutually interlinked—each step paves the way for the next.

Of the described four stages, only stage three focuses a classical linguistic task: the description of a new genre of text. The remaining three take a broader view informed by sociology and philosophy, focusing on discursive practices i.e., language used in social context. Other descriptions of the emergence of impact are possible—note for instance Power’s four-fold structure (Power, 2015 ), at points analogous to this study.

Theoretical framework and data

This study builds on a constructivist approach to social phenomena in assuming that language plays a crucial role in establishing and maintaining social practice. In this approach ‘discourse’ is understood as the production of social meaning—or the negotiation of social, political or cultural order—through the means of text and talk (Fairclough, 1989 , 1992 ; Fairclough et al., 1997 ; Gee, 2015 ).

Linguistic pragmatics and Foucauldian approaches to discourse are used to account for the changes related to the rise of ‘impact’ as element of evaluation and discourse on the macro and micro scale. In looking at the micro scale of every-day linguistic practices the analysis makes use of linguistic pragmatics, in particular concepts of positioning (Davies and Harré, 1990 ), stage (Goffman, 1969 ; Robinson, 2013 ), metaphor (Cameron, et al., 2009 ; Musolff, 2004 , 2012 ), as well as genre analysis (Swales, 1990 , 2011 ). Analyzing the macro scale, i.e., the establishment of the concept of ‘impact’ in policy and the creation of an impact infrastructure, it draws on selected concepts of Fouculadian governmentality theory (crucially ‘problematisation’, ‘apparatus’, ‘subjectivation’) (Foucault, 1980 , 1988 , 1990 ; Rose, 1999 , pp. ix–xiii).

While the toolbox of linguistic pragmatics is particularly useful in analyzing linguistic aspects of the datasets, Foucault’s governmental framework helps bring together findings from the two datasets in a broader analysis, allowing more general conclusions on the practices of governing (academic) subjects within evaluation frameworks. Both pragmatic and Foucauldian traditions of discourse analysis have been productively applied in the study of higher education contexts (e.g., Fairclough, 1993 , Gilbert and Mulkey, 1984 , Hyland, 2009 , Myers, 1985 , 1989 ; for an overview see Wróblewska and Angermuller, 2017 ).

The analysis builds on an admittedly heterogenous set of concepts, hailing from different traditions and disciplines. This approach allows for a suitably nuanced description of a broad phenomenon—the discourse of impact—studied here on the basis of two different datasets. To facilitate following the argument, individual theoretical and methodological concepts are defined where they are applied in the analysis.

The studied corpus consists of two datasets: a written and oral one. The written corpus includes 78 impact case studies (CSs) submitted to REF2014 in the discipline of linguistics Footnote 1 . Linguistics was selected as a discipline straddling the social sciences and humanities (SSH). SSH are arguably most challenged by the practice of impact evaluation as they have traditionally resisted subjection to economization and social accountability (Benneworth et al., 2016 ; Bulaitis, 2017 ).

The CSs were downloaded in pdf form from REF’s website: https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/ . The documents have an identical structure, featuring basic information: name of institution, unit of assessment, title of CS and core content divided into five sections: (1) summary of impact, (2) underpinning research, (3) references to the research, (4) details of impact (5) sources to corroborate impact. Each CS is about 4 pages long (~2400 words). The written dataset (with a word-count of 173,474) was analyzed qualitatively using MAX QDA software with a focus on the generic aspect of the documents.

The oral dataset is composed of semi-structured interviews with authors of the studied CSs ( n = 20) and other actors involved in the evaluation, including two policy-makers and three academic administrators Footnote 2 . In total, the 25 interviews, each around 60 min long, add up to around 25 h of recordings. The interviews were analyzed in two ways. Firstly, they were coded for themes and topics related to the evaluation process—this was useful for the description of impact infrastructure presented in step 2 of analysis. Secondly, they were considered as a linguistic performance and coded for discursive devices (irony, distancing, metaphor etc.)—this was the basis for findings related to the presentation of one’s ‘academic self’ which are the object of fourth step of analysis. The written corpus allows for an analysis of the functioning of the notion of ‘impact’ in the official, administrative discourse of academia, looking at the emergence of an impact infrastructure and the genre created for the description of impact. The oral dataset in turn sheds light on how academics relate to the notion of impact in informal settings, by focusing on metaphors and pragmatic markers of stage.

The discourse of impact

Problematization of impact.

The introduction of ‘impact’, a new element of evaluation accounting for 20% of the final result, was seen as a surprise and as a significant change in respect to the previous model of evaluation—the Research Assessment Exercise (Warner, 2015 ). The outline of an approach to impact evaluation in REF was developed on the government’s recommendation after a review of international practice in impact assessment (Grant et al., 2009 ). The adopted approach was inspired by the previously-created (but never implemented) Australian RQF framework (Donovan, 2008 ). A pilot evaluation exercise run in 2010 confirmed the viability of the case-study approach to impact evaluation. In July 2011 the Higher Education Council for England (HEFCE) published guidelines regulating the new assessment (HEFCE, 2011 ). The deadline for submissions was set for November 2013.

In the period between July 2011 and November 2013 HEFCE engaged in broad communication and training activities across universities, with the aim of explaining the concept of ‘impact’ and the rules which would govern its evaluation (Power, 2015 , pp. 43–48). Knowledge on the new element of evaluation was articulated and passed down to particular departments, academic administrative staff and individual researchers in a trickle-down process, as explained by a HEFCE policymaker in an account of the run-up to REF2014:

There was no master blue print! There were some ideas, which indeed largely came to pass. But in order to understand where we [HEFCE] might be doing things that were unhelpful and might have adverse outcomes, we had to listen. I was in way over one hundred meetings and talked to thousands of people! (…) [The Impact Agenda] is something that we are doing to universities. Actually, what we wanted to say is: ‘we are doing it with you, you’ve Footnote 3 got to own it’.

Int20, policymaker, example 1 Footnote 4

Due to the importance attributed to the exercise by managers of academic units and the relatively short time for preparing submissions, institutions were responsive to the policy developments. In fact, they actively contributed to the establishment and refinement of concepts related to impact. Institutional learning occurred to a large degree contemporarily to the consolidation of the policy and the refinement of the concepts and definitions related to impact. The initially open, undefined nature of ‘impact’ (“there was no master blue-print”) is described also in accounts of academics who participated in the many rounds of meetings and consultations. See example 2 below:

At that time, they [HEFCE] had not yet come up with this definition [of impact], not yet pinned it down, but they were trying to give an idea of what it was, to get feedback, to get a grip on it. (…) And we realised (…) they didn’t have any more of an idea of this than we did! It was almost like a fishing expedition. (…) I got a sense very early on of, you know, groping.

Int1, academic, example 2

The “pinning down” of an initially fuzzy concept and defining the rules which would come to govern its evaluation was just one aim of the process. The other one was to engage academics and affirm their active role in the policy-making. From an idea which came from outside of the British academic community (from the the government, the research councils) and originally from outside the UK (the Australian RQF exercise), a concept which was imposed on academics (“it is something that we are doing to universities”) the Impact Agenda was to become an accepted, embedded element of the academic life (“you’ve got to own it”). In this sense, the laboriousness of the process, both for the policy-makers and the academics involved, was a necessary price to be paid for the feeling of “ownership” among the academic community. Attitudes of academics, initially quite negative (Chubb et al., 2016 , Watermeyer, 2016 ), changed progressively, as the concept of impact became familiarized and adapted to the pre-existing realities of academic life, as recounted by many of the interviewees, e.g.,:

I think the resentment died down relatively quickly. There was still some resistance. And that was partly academics recognising that they had to [take part in the exercise], they couldn’t ignore it. Partly, the government and the research council has been willing to tweak, amend and qualify the initial very hard-edged guidelines and adapt them for the humanities. So, it was two-way process, a dialogue.

Int16, academic, example 3

The announcement of the final REF regulations (HEFCE, 2011 ) was the climax of the long process of making ‘impact’ into a thinkable and manageable entity. The last iteration of the regulations constituted a co-creation of various actors (initial Australian policymakers of the RQF, HEFCE employees, academics, impact professionals, universities, professional organizations) who had contributed to it at different stages (in many rounds of consultations, workshops, talks and sessions across the country). ‘Impact’ as a notion was ‘talked into being’ in a polyphonic process (Angermuller, 2014a , 2014b ) of debate, critique, consultation (“listening”, “getting feedback”) and adaptation (“tweaking”, “changing”, “amending hard-edged guidelines”) also in view of the pre-existing conditions of academia such as the friction between the ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ sciences (as mentioned in example 3). In effect, impact was constituted as an object of thought, and an area of academic activity begun to emerge around it.

The period of defining ‘impact’ as a new, important notion in academic discourse in the UK, roughly between July 2011 and November 2013, can be conceptualized in terms of the Foucauldian notion of ‘problematization’. This concept describes how spaces, areas of activity, persons, behaviors or practices become targeted by government, separated from others, and cast as ‘problems’ to be addressed with a set of techniques and regulations. ‘Problematisation’ is the moment when a notion “enters into the play of true and false, (…) is constituted as an object of thought (whether in the form of moral reflection, scientific knowledge, political analysis, etc.)” (Foucault, 1988 , p. 257), when it “enters into the field of meaning” (Foucault, 1984 , pp. 84–86). The problematization of an area triggers not only the establishment of new notions and objects but also of new practices and institutions. In consequence, the areas in question become subjugated to a new (political, administrative, financial) domination. This eventually shapes the way in which social subjects conceive of their world and of themselves. But a ‘problematisation’, however influential, cannot persist on its own. It requires an overarching structure in the form of an ‘apparatus’ which will consolidate and perpetuate it.

Impact infrastructure

Soon after the publication of the evaluation guidelines for REF2014, and still during the phase of ‘problematisation’ of impact, universities started collecting data on ‘impactful’ research conducted in their departments and recruiting authors of potential CSs which could be submitted for evaluation. The winding and iterative nature of the process of problematization of ‘impact’ made it difficult for research managers and researchers to keep track of the emerging knowledge around impact (official HEFCE documentation, results of the pilot evaluation, FAQs, workshops and sessions organized around the country, writings published in paper and online). At the stage of collecting drafts of CSs it was still unclear what would ‘count’ as impact and what evidence would be required. Hence, there emerged a need for specific procedures and specialized staff who would prepare the REF submissions.

At most institutions, specific posts were created for employees preparing impact submissions for REF2014. These were both secondment positions such as ‘impact lead’, ‘impact champion’ and full-time ones such as impact officer, impact manager. These professionals soon started organizing between themselves at meetings and workshops. Administrative units focused on impact (such as centers for impact and engagement, offices for impact and innovation) were created at many institutions. A body of knowledge on impact evaluation was soon consolidated, along with a specific vocabulary (‘a REF-able piece of research’, ‘pathways to impact’, ‘REF-readiness’ etc.) and sets of resources. Impact evaluation gave raise to the creation of a new type of specialized university employee, who in turn contributed to turning the ‘generation of impact’, as well as the collection and presentation of related data into a veritable field of professional expertize.

In order to ensure timely delivery of CSs to REF2014, institutions established fixed procedures related to the new practice of impact evaluation (periodic monitoring of impact, reporting on impact-related activities), frames (schedules, document templates), forms of knowledge transfer (workshops on impact generation or on writing in the CS genre), data systems and repositories for logging and storing impact-related data, and finally awards and grants for those with achievements (or potential) related to impact. Consultancy companies started offering commercial services focused on research impact, catering to universities and university departments but also to governments and research councils outside the UK looking at solutions for impact evaluation. There is even an online portal with a specific focus on showcasing researchers’ impact (Impact Story).

In consequence, impact became institutionalized as yet another “box to be ticked” on the list of academic achievements, another component of “academic excellence”. Alongside burdens connected to reporting on impact and following regulations in the area, there came also rewards. The rise of impact as a new (or newly-problematised) area of academic life opened up uncharted areas to be explored and opportunities for those who wished to prove themselves. These included jobs for those who had acquired (or could claim) expertize in the area of impact (Donovan, 2017 , p. 3) and research avenues for those studying higher education and evaluation (after all, entirely new evaluation practices rarely emerge, as stressed by Power, 2015 , p. 43). While much writing on the Impact Agenda highlights negative attitudes towards the exercise (Chubb et al., 2016 ; Sayer, 2015 ), equally worth noting are the opportunities that the establishment of a new element of the exercise opened. It is the energy of all those who engage with the concept (even in a critical way) that contributes to making it visible, real and robust.

The establishment of a specialized vocabulary, of formalized requirements and procedures, the creation of dedicated impact-related positions and departments, etc. contribute to the establishment of what can be described as an ‘impact infrastructure’ (comp. Power, 2015 , p. 50) or in terms of Foucauldian governmentality theory as an ‘apparatus’ Footnote 5 . In Foucault’s terminology, ‘apparatus’ refers to a formation which encompasses the entirety of organizing practices (rituals, mechanisms, technologies) but also assumptions, expectations and values. It is the system of relations established between discursive and non-discursive elements as diverse as “institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions” (Foucault, 1980 , p. 194). An apparatus servers a specific strategic function—responding to an urgent need which arises in a concrete time in history—for instance, regulating the behavior of a population.

There is a crucial discursive element to all the elements of the ‘impact apparatus’. While the creation of organizational units and jobs, the establishment of procedures and regulations, participation in meetings and workshops are no doubt ‘hard facts’ of academic life, they are nevertheless brought about and made real in discursive acts of naming, defining, delimiting and evaluating. The aim of the apparatus was to support the newly-established problematization of impact. It did so by operating on many levels: first of all, and most visibly, newly-established procedures enabled a timely and organized submission to the upcoming REF. Secondly, the apparatus guided the behavior of social actors. It did so not only through directive methods (enforcing impact-related requirements) but also through nurturing attitudes and dispositions which are necessary for the notion of impact to take root in academia (for instance via impact training delivered to early-career scholars).

Interviewed actors involved in implementing the policy in institutions recognized their role in orchestrating collective learning. An interviewed impact officer stated:

My feeling is that ultimately my post should not exist. In ten or fifteen years’ time, impact officers should have embedded the message [about impact] firmly enough that they [researchers] don’t need us anymore.

Int7, impact officer, example 4

A similar vision was evoked by a HEFCE policymaker who was asked if the notion of impact had become embedded in academic institutions:

I hope [after the next edition of REF] we will be able to say that it has become embedded. I think the question then will be “have we done enough in terms of case studies? Do we need something very much lighter-touch?” “Do we need anything at all?”—that’s a question. (…) If [impact] is embedded you don’t need to talk about it.

Int20, policy-maker, example 5

Rather than being an aim in itself, the Impact Agenda is a means of altering academic culture so that institutions and individual researchers become more mindful of the societal impacts of their research. The instillment of a “new impact culture” (see Manville et al., 2014 , pp. 24–29) would ensure that academic subjects consider the question of ‘impact’ even outside of the framework of REF. The “culture shift” is to occur not just within institutions but ultimately within the subjects—it is in them that the notion of ‘impact’ has to become embedded. Hence, the final purpose of the apparatus would be to obscure the origins of the notion of ‘impact’ and the related practices, neutralizing the notion itself, and giving a guise of necessity to an evaluative reality which in fact is new and contingent.

The genre of impact case study as element of infrastructure

In this section two questions are addressed: (1) what are the features of the genre (or what is it like?) and (2) what are the functions of the genre (or what does it do? what vision of research does it instil?). In addressing the first question, I look at narrative patterns, as well as lexical and grammatical features of the genre. This part of the study draws on classical genre analysis (Bhatia, 1993 ; Swales, 1998 ) Footnote 6 . The second question builds on the recognition, present in discourse studies since the 1970s’, that genres are not merely classes of texts with similar properties, but also veritable ‘dispositives of communication’. A genre is a means of articulation of legitimate speech; it does not just represent facts or reflect ideologies, it also acts on and alters the context in which it operates (Maingueneau, 2010 , pp. 6–7). This awareness has engendered broader sociological approaches to genre which include their pragmatic functioning in institutional realities (Swales, 1998 ).

The genre of CS differs from other academic genres in that it did not emerge organically, but was established with a set of guidelines and a document template at a precise moment in time. The genre is partly reproductive, as it recycles existing patterns of academic texts, such as journal article, grant application, annual review, as well as case study templates applied elsewhere. The studied corpus is strikingly uniform, testifying to an established command of the genre amongst submitting authors. Identical expressions are used to describe impact across the corpus. Only very rarely is non-standard vocabulary used (e.g., “horizontal” and “vertical” impact rather then “reach” and “significance” of impact). This coherence can be contrasted with a much more diversified corpus of impact CSs submitted in Norway to an analogous exercise (Wróblewska, 2019 ). The rapid consolidation of the genre in British academia can be attributed to the perceived importance of impact evaluation exercise, which lead to the establishment of an impact infrastructure, with dedicated employees tasked with instilling the ‘culture of impact’.

In its nature, the CS is a performative, persuasive genre—its purpose is to convince the ‘ideal readers’ (the evaluators) of the quality of the underpinning research and the ‘breadth and significance’ of the described impact. The main characteristics of the genre stem directly from its persuasive aim. These are discussed below in terms of narrative patterns, and grammatical and lexical features.

Narrative patterns

On the level of narrative, there is an observable reliance on a generic pattern of story-telling frequent in fiction genres, such as myths or legends, namely the Situation-Problem–Response–Evaluation (SPRE) structure (also known as the Problem-Solution pattern, see Hoey, 1994 , 2001 pp. 123–124). This is a well-known narrative which follows the SPRE pattern: a mountain ruled by a dragon (situation) which threats the neighboring town (problem) is sieged by a group of heroes (response), to lead to a happy ending or a new adventure (evaluation). Compare this to an example of the SPRE pattern in a sample impact narrative from the studied corpus:

Mosetén is an endangered language spoken by approximately 800 indigenous people (…) (SITUATION). Many Mosetén children only learn the majority language, Spanish (PROBLEM). Research at [University] has resulted in the development of language materials for the Mosetenes. (…) (RESPONSE). It has therefore had a direct influence in avoiding linguistic and cultural loss. (EVALUATION).

CS40828 Footnote 7

The SPRE pattern is complemented by patterns of Further Impact and Further Corroboration. The first one allows elaborating the narrative, e.g., by showing additional (positive) outcomes, so that the impact is not presented as an isolated event, but rather as the beginning of a series of collaborations, e.g.,:

The research was published in [outlet] (…). This led to an invitation from the United Nations Environment Programme for [researcher](FURTHER IMPACT).

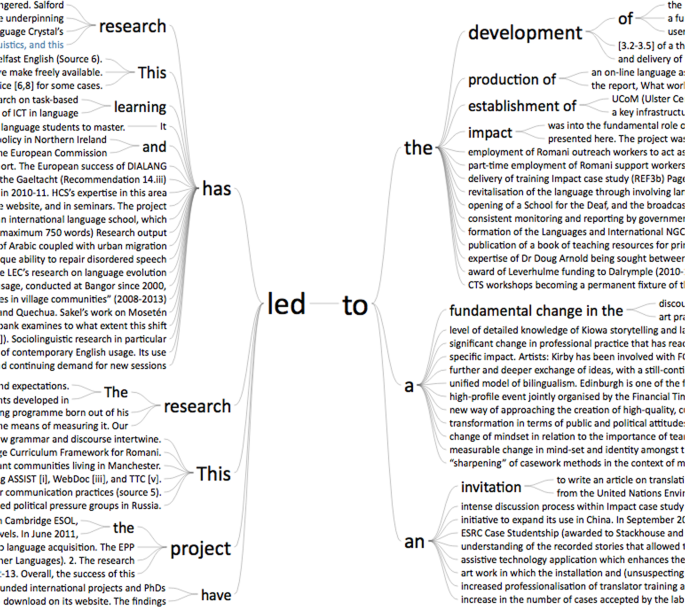

Patterns of ‘further impact’ are often built around linking words, such as: “X led to” ( n = 78) Footnote 8 , “as a result” ( n in the corpus =31), “leading to” ( n = 24), “resulting in” ( n = 13), “followed” (“X followed Y”– n = 14). Figure 1 below shows a ‘word tree’ for a frequent linking structure “led to”. The size of the terms in the diagram represents frequencies of terms in the corpus. Reading the word tree from left to right enables following typical sentence structures built around the ‘led to’ phrase: research led to an impact (fundamental change/development/establishment/production of…); impact “led to” further impact.

Word tree with string ‘led to'. This word tree with string ‘led to’ was prepared with MaxQDA software. It visualises a frequent sentence structure where research led to impact (fundamental change/ development/ establishment/ production of…) or otherwise how impact “led to” further impact.

The ‘Further Corroboration’ pattern provides additional information which strengthens the previously provided corroborative material:

(T)he book has been used on the (…) course rated outstanding by Ofsted, at the University [Name](FURTHER CORROBORATION).

Grammatical and lexical features

Both on a grammatical and lexical level, there is a visible focus on numbers and size. In making the point on the breadth and significance of impact, CS authors frequently showcase (high) numbers related to the research audience (numbers of copies sold, audience sizes, downloads but also, increasingly, tweets, likes, Facebook friends and followers). Adjectives used in the CSs appear frequently in the superlative or with modifiers which intensify them: “Professor [name] undertook a major Footnote 9 ESRC funded project”; “[the database] now hosts one of the world’s largest and richest collections (…) of corpora”; “work which meets the highest standards of international lexicographical practice”; “this experience (…) is extremely empowering for local communities”, “Reach: Worldwide and huge ”.

Use of ‘positive words’ constitutes part of the same phenomenon. These appear often in the main narrative on research and impact, and even more frequently in quoted testimonials. Research is described in the CSs as being new, unique and important with the use of words such as “innovative” ( n = 29), “influential” ( n = 16), “outstanding” ( n = 12), “novel” ( n = 10), “excellent” ( n = 8), “ground-breaking” ( n = 7), “tremendous” ( n = 4), “path-breaking” ( n = 2), etc. The same qualities are also rendered descriptively, with the use of words that can be qualified as boosters e.g., “[the research] has enabled a complete rethink of the relationship between [areas]”; “ vitally important [research]”.

Novelty of research is also frequently highlighted with the adjective “first” appearing in the corpus 70 times Footnote 10 . While in itself “first” is not positive or negative, it carries a big charge in the academic world where primacy of discovery is key. Authors often boast about having for the first time produced a type of research—“this was the first handbook of discourse studies written”…, studied a particular area—“This is the first text-oriented discourse analytic study”…, compiled a type of data—“[We] provid[ed] for the first time reliable nationwide data”; “[the] project created the first on-line database of…”, or proven a thesis: “this research was the first to show that”…

Another striking lexical characteristic of the CSs is the presence of fixed expressions in the narrative on research impact. I refer to these as ‘impact speak’. There are several collocations with ‘impact’, the most frequent being “impact on” ( n = 103) followed by the ‘type’ of impact achieved (impact on knowledge), area/topic (impact on curricula) or audience (Impact on Professional Interpreters). This collocation often includes qualifiers of impact such as “significant”, “wide”, “primary”,“secondary”, “broader”, “key”, and boosters: great, positive, wide, notable, substantial, worldwide, major, fundamental, immense etc. Impact featured in the corpus also as a transitive verb ( n = 22) in the forms “impacted” and “impacting”—e.g., “[research] has (…) impacted on public values and discourse”. This is interesting, as use of ‘impact’ as a verb is still often considered colloquial. Verb collocations with ‘impact’ are connected to achieving influence (“lead to..”, “maximize…”, “deliver impact”) and proving the existence and quality of impact (“to claim”, “to corroborate” impact, “to vouch for” impact, “to confirm” impact, to “give evidence” for impact). Another salient collocation is “pathways to impact” ( n = 14), an expression describing channels of interacting with the public, in the corpus occasionally shortened to just “pathways” e.g., “The pathways have been primarily via consultancy”. This phrase has most likely made its way to the genre of CS from the Research Councils UK ‘Pathways to Impact’ format introduced as part of grant applications in 2009 (discontinued in early 2020).

On a syntactic level, CSs are rich in parallel constructions of enumeration, for instance: “ (t)ranslators, lawyers, schools, colleges and the wider public of Welsh speakers are among (…) users [of research]”; “the research has benefited a broad, international user base including endangered language speakers and community members, language activists, poets and others ”; [the users of the research come] “from various countries including India, Turkey, China, South Korea, Venezuela, Uzbekistan, and Japan ”. Listing, alongside providing figures, is one of the standard ways of signaling the breadth and significance of impact. Both lists and superlatives support the persuasive function of the genre. In terms of verbal forms, passive verbs are clearly favored and personal pronouns (“I, we”) are avoided: “research was conducted”, “advice was provided”, “contracts were undertaken”.

Vision of research promoted by the genre of CS

Impact CS is a new, influential genre which affects its academic context by celebrating and inviting a particular vision of successful research and impact. It sets a standard for capturing and describing a newly-problematized academic object. This standard will be a point of reference for future authors of CSs. Hence, it is worth taking a look at the vision on research it instills.

The SPRE pattern used in the studied CSs favors a vision of research that is linear: work proceeds from research question to results without interference. The Situation and Problem elements are underplayed in favor of elaborate descriptions of the researchers’ ‘Reactions’ (research and outreach/impact activities) and flattering ‘Evaluations’ (descriptions of effects of the research and data supporting these claims). Most narratives are devoid of challenges (the ‘Problem’ element is underplayed, possible drawbacks and failures in the research process are mentioned sporadically). Furthermore, narratives are clearly goal-oriented: impact is shown as included in the research design from the beginning (e.g., impact is frequently mentioned already in section 2 ‘Underpinning research’, rather than the latter one ‘Details of the impact’). Elements of chance, luck, serendipity in the research process are erased—this is reinforced by the presence of patterns of ‘further proof’ and ‘further corroboration’. As such, the bulk of studied CSs channel a vision of what is referred to in Science Studies as ‘normal’ (deterministic, linear) science (Kuhn, 1970 , pp. 10–42). From a purely literary perspective this makes for rather dull narratives: “fairy-tales of researcher-heroes… but with no dragons to be slain” (Selby, 2016 ).

The few CSs which do discuss obstacles in the research process or in securing impact stand out as strikingly diverse from the rest of the corpus. Paradoxically, while apparently ‘weakening’ the argumentation, they render it more engaging and convincing. This effect has been observed also in in an analogous corpus of Norwegian CSs which tend to problematize the pathway from research to impact to a much higher degree (Wróblewska, 2019 , pp. 34–35).