- International Peace and Security

- Higher Education and Research in Africa

- Andrew Carnegie Fellows

- Great Immigrants

- Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy

- Reporting Requirements

- Modification Requests

- Communications FAQs

- Grants Database

- Philanthropic Resources

- Grantee FAQs

- Grantmaking Highlights

- Past Presidents

- The Gospel of Wealth

- Other Carnegie Organizations

- Andrew Carnegie’s Story

- Governance and Policies

- Media Center

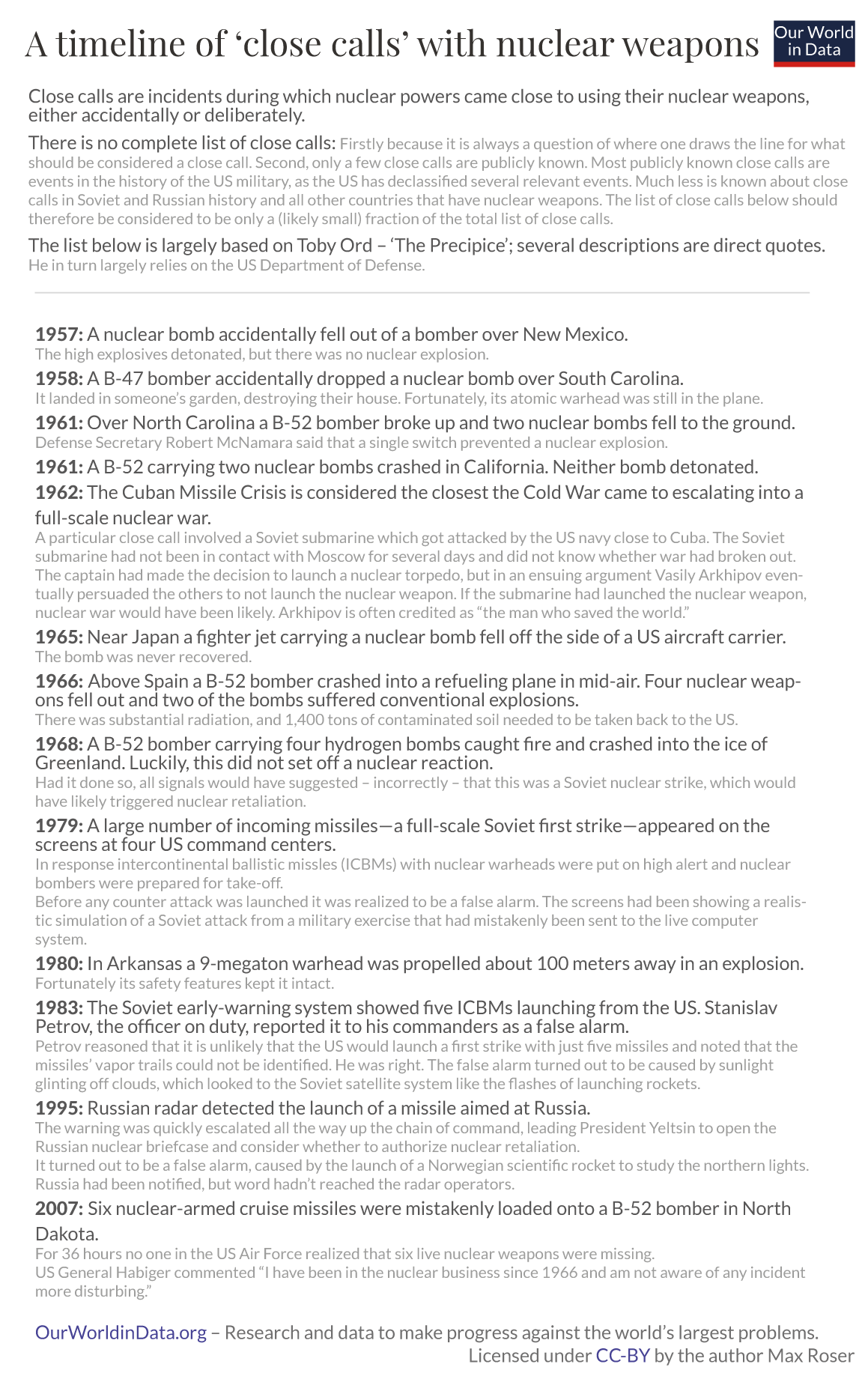

What Questions Should Humans Be Asking about Nuclear Weapons?

In June 2023, we asked ChatGPT this question. Here is its exact response — unedited, uncorrected, uncanny

Question : What questions should humans be asking about nuclear weapons?

ChatGPT Answer: Nuclear weapons are one of the most destructive and deadly weapons ever created, and their existence poses a significant threat to global security. Here are some questions that humans should be asking about nuclear weapons:

- How can we prevent the use of nuclear weapons? This includes preventing nuclear war, accidental detonations, and unauthorized access to nuclear weapons.

- What are the risks associated with nuclear weapons? This includes the potential for nuclear accidents, the environmental and health impacts of nuclear testing and use, and the geopolitical risks associated with nuclear proliferation.

- What role should nuclear weapons play in national security strategies? Is it ethical to possess and potentially use such destructive weapons, and what are the potential consequences of doing so?

- How can we reduce the global nuclear weapons stockpile? This includes arms control agreements, disarmament efforts, and the safe and secure storage and disposal of nuclear materials.

- How can we address the challenges posed by emerging technologies, such as hypersonic missiles, in the context of nuclear weapons?

- How can we improve international cooperation and dialogue on nuclear weapons? This includes diplomatic efforts to reduce tensions and increase transparency between nuclear-armed states.

These are just a few examples of the many questions that humans should be asking about nuclear weapons. It is important to have ongoing discussions and evaluations of nuclear weapons policies and strategies to ensure that we are reducing the risks associated with these weapons and moving towards a more peaceful and secure world.

ChatGPT is an artificial intelligence-powered language model developed by OpenAI.

States are offering incentives to strengthen America’s volunteer tradition – the “golden thread” of U.S. democracy

With the philanthropic support of Carnegie Corporation of New York, thousands of newly digitized, high-quality images of medieval manuscripts are now freely available to the public

Programs submenu

Regions submenu, topics submenu, solving the world’s hardest problems with mellody hobson: closing the racial wealth gap, weapons in space: a virtual book talk with dr. aaron bateman, u.s.-australia-japan trilateral cooperation on strategic stability in the taiwan strait report launch.

- Abshire-Inamori Leadership Academy

- Aerospace Security Project

- Africa Program

- Americas Program

- Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy

- Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative

- Asia Program

- Australia Chair

- Brzezinski Chair in Global Security and Geostrategy

- Brzezinski Institute on Geostrategy

- Chair in U.S.-India Policy Studies

- China Power Project

- Chinese Business and Economics

- Defending Democratic Institutions

- Defense-Industrial Initiatives Group

- Defense 360

- Defense Budget Analysis

- Diversity and Leadership in International Affairs Project

- Economics Program

- Emeritus Chair in Strategy

- Energy Security and Climate Change Program

- Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program

- Freeman Chair in China Studies

- Futures Lab

- Geoeconomic Council of Advisers

- Global Food and Water Security Program

- Global Health Policy Center

- Hess Center for New Frontiers

- Human Rights Initiative

- Humanitarian Agenda

- Intelligence, National Security, and Technology Program

- International Security Program

- Japan Chair

- Kissinger Chair

- Korea Chair

- Langone Chair in American Leadership

- Middle East Program

- Missile Defense Project

- Project on Critical Minerals Security

- Project on Fragility and Mobility

- Project on Nuclear Issues

- Project on Prosperity and Development

- Project on Trade and Technology

- Renewing American Innovation

- Scholl Chair in International Business

- Smart Women, Smart Power

- Southeast Asia Program

- Stephenson Ocean Security Project

- Strategic Technologies Program

- Sustainable Development and Resilience Initiative

- Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies

- Warfare, Irregular Threats, and Terrorism Program

- All Regions

- Australia, New Zealand & Pacific

- Middle East

- Russia and Eurasia

- American Innovation

- Civic Education

- Climate Change

- Cybersecurity

- Defense Budget and Acquisition

- Defense and Security

- Energy and Sustainability

- Food Security

- Gender and International Security

- Geopolitics

- Global Health

- Human Rights

- Humanitarian Assistance

- Intelligence

- International Development

- Maritime Issues and Oceans

- Missile Defense

- Nuclear Issues

- Transnational Threats

- Water Security

Thinking about the Unthinkable: Five Nuclear Weapons Issues to Address in 2024

Photo: Mikhail Svetlov/Getty Images

Commentary by Kelsey Hartigan

Published February 9, 2024

As the United States gears up for a presidential election and the administration juggles support to Ukraine, growing conflict in the Middle East, and a host of other challenges, Washington will need to address five key nuclear weapons challenges in 2024. Managing Russia’s nuclear threats, China’s opaque nuclear buildup, and North Korea’s increasing provocations—and the increasingly close relationships among them—will be no easy feat. At the same time, Washington will need to navigate its extended deterrence commitments and efforts to better integrate with U.S. allies and finally organize for a series of consequential, long-term decisions on the future of the U.S. nuclear arsenal. While a high-intensity war with China or Russia or a major conflict with North Korea is not inevitable, the pathways to potential conflicts are increasing, and so too are the risks of nuclear use—especially limited nuclear use. With an exceedingly complex international security environment, policymakers, planners, and legislatures need to think about the unthinkable this year and take action. Detering nuclear use requires a sober assessment of the new and changing ways adversaries are attempting to leverage nuclear weapons and clear-eyed plans for how to manage nuclear threats if deterrence fails.

Here are the top five nuclear issues to address in 2024:

- Russia’s Nuclear Threats and the War in Ukraine

As the war in Ukraine enters its third year and the administration and Congress debate future U.S. security assistance to Ukraine, a key question will be how Russia’s nuclear signaling and threats will evolve in 2024 and how the trajectory of the conflict will affect the potential for nuclear use. While the risk of use likely remains low amid the current stalemate, significant changes on the ground, such as a significant spike in attacks deep inside Russia, could affect that calculus. In addition, with increased cooperation between Russia and North Korea (and Iran) and confirmation that North Korea is providing Russia with ballistic missiles and ballistic missile launchers, another key question will be to what extent this kind of assistance affects the situation on the ground, whether this prolongs the conflict, and how this affects overall escalation dynamics. With the intelligence community assessing that “Moscow will become even more reliant on nuclear, cyber, and space capabilities as it deals with the extensive damage to Russia’s ground forces,” nuclear risks could actually grow in the coming months and years, making it essential that Washington, NATO, and Kyiv remain prepared and clear-eyed about how to handle a range of scenarios, especially those involving “ battlefield” nuclear weapons and limited nuclear use.

In addition, while U.S. officials have indicated that they have not yet seen changes to Russia’s strategic nuclear forces since it suspended New START, without onsite inspections or data exchanges, it may become more difficult over time to maintain confidence that there have been no militarily significant operational changes to Russia’s strategic forces using national technical means alone. This means there will be very few guardrails on the broader U.S.-Russia strategic relationship, making it—as well as Russia’s efforts to deliberately manipulate nuclear risks in Ukraine and beyond—one of the top nuclear issues to watch in 2024.

- China’s Nuclear Buildup

China’s rapid expansion and diversification of its nuclear forces also demands attention in 2024. While the administration has made clear that “the United States does not need to increase our nuclear forces to outnumber the combined total of our competitors in order to successfully deter them,” a number of recent high-profile commissions, reports , and studies argue for important changes to U.S. nuclear forces, setting up a renewed debate over what’s driving China’s nuclear buildup and whether and how the United States should respond . China’s nuclear buildup cannot be viewed in isolation, however. This is fundamentally a question of whether the United States has the necessary force structure to manage concurrent or sequential conflicts with two nuclear-armed adversaries—a force-sizing construct the Pentagon abandoned years ago (and never truly had to address in the same way).

At the same time, the debate over potential changes to the size and composition of U.S. nuclear forces cannot mask questions over how Washington and its allies would respond to Chinese nuclear coercion or even limited nuclear use in certain scenarios, particularly a Taiwan crisis . Such a crisis could occur well before any changes to the current program of record materialize, and China is no doubt watching how Russia is deliberately manipulating nuclear risks in the war in Ukraine. With continued cross-Strait tensions and an uncertain future for the broader U.S.-China relationship, it is essential that officials understand the conditions under which China might use nuclear weapons and be prepared to manage the nuclear shadow that will loom over virtually any conventional conflict in the Indo-Pacific. Arms control talks with China may help improve this understanding over time, but recent efforts to engage on these issues are unlikely to translate into a reliable risk reduction mechanism any time soon or change the operational dilemmas U.S. forces might encounter. This means that Washington and its allies need to deepen planning and consultations in 2024 on managing the nuclear shadow with China for if and when a conflict occurs and ensure that these efforts are fully integrated into broader defense planning efforts.

- Tensions with North Korea and Opportunistic Aggression

In his New Year address, Kim Jong-unn warned that North Korea needs to prepare for war with the United States in 2024 and pointed to the U.S.-Republic of Korea (ROK) Washington Declaration, increased trilateral exercises, and the more visible presence of U.S. strategic assets as the reason behind the North’s aggressive posturing. While to some extent, this kind of rhetoric and blame game is more of the same— especially in an election year —North Korea’s continued quantitative and qualitative growth of its nuclear and ballistic missile programs, including both long-range systems capable of striking the United States and its increasing emphasis on tactical nuclear weapons, pose serious threats to the United States, ROK, and Japan that cannot be ignored or wished away. Washington and Seoul cannot deter missile tests or satellite launches, but they can take steps to ensure U.S. and ROK forces are prepared for both major conflicts as well as localized attacks , which can in turn help deter a war that no one wants. This requires consistently updating plans and assumptions, clarifying roles and responsibilities, and maintaining readiness for a wide range of North Korea contingencies. Maintaining this focus can be difficult given all of the demands on U.S. forces and the attention on great power competition, but it is essential.

At the same time, tensions on the Korean Peninsula don’t exist in a vacuum, and possible North Korean contingencies or conflicts cannot be planned against in isolation . As North Korea and Russia step up their cooperation, ties between Russia and China increase, and China and North Korea rekindle links, 2024 will unfortunately likely serve as a reminder that it is not enough to focus on managing individual flashpoints with Russia and China. If the United States finds itself in a conventional conflict with China or Russia, it could provide a dangerous opening for North Korea to exploit, just as a conflict with North Korea could leave the United States and its allies dangerously unprepared to manage a bubbling over of tensions with Russia or China (Russia and China could also of course take advantage of regional conflicts in separate theaters, which would pose even greater constraints).

Understanding and better preparing for the risks and tradeoffs associated with these types of opportunistic aggression scenarios, whether coordinated or not, should be a top priority in 2024. This will require, among many things, difficult and frank consultations on the limitations and possible roles and responsibilities across various alliance structures in the Indo-Pacific, as well as with NATO allies.

- U.S. Extended Deterrence Commitments and Integration with U.S. Allies

U.S. allies are understandably skeptical over whether the United States can and will maintain its alliance commitments. Managing these concerns—especially in an election year—will require continued time and attention, a requirement many U.S. allies in Europe and Asia worry could be increasingly difficult given the upcoming election and deteriorating situation in the Middle East and the demands the region is once again placing on U.S. officials. The Biden administration took important steps in 2023 to strengthen alliances and extended deterrence assurances to U.S. allies, and deepen planning and coordination on key crisis management issues. Finding ways to institutionalize and deepen these efforts will be critical. These efforts should focus on a range of possible conflict scenarios with Russia, China, and North Korea and dig into some hard questions: What specifically do various alliances intend to deter? Who would do what in a crisis? What might be perceived as escalatory? How would allies communicate with one another and the public during a contingency? How might various alliances might integrate conventional and nuclear operations during a crisis, or take certain actions to deter opportunistic aggression?

It will also be important to watch how Washington postures its nuclear forces over the next year to both assure allies and demonstrate its readiness and resolve to U.S. adversaries. The United States has shifted to a much more dynamic mode of messaging and communicating its nuclear force movements—from a significant uptick in bomber task force missions to a much more visible presence for U.S. ballistic missile submarines . Going forward, officials need to take a holistic look at what effect these measures have (and what the implications for future force management decisions might be) and find opportunities to monitor how certain actions or exercises in one theater register, or not, with adversaries in another.

- Progress on U.S. Nuclear Modernization

Finally, with such a dynamic threat environment, 2024 will be a critical year for the nuclear enterprise. Every major element of U.S. nuclear forces is being modernized. But delays, budget overruns , supply chain issues, and significant workforce and infrastructure constraints across both the defense and national lab sectors are leading to an increasing disconnect between policy debates over what might be needed in the future and the reality of what the existing workforce and infrastructure can support. This needs to change in 2024. Congress needs to change the way it oversees defense and National Nuclear Security Administration programs and work with the Pentagon to enact significant changes to the way the enterprise assesses risks—not just the risks of delays across the nuclear enterprise but also to conventional acquisition programs that are critical to our ability to deter, and prevail in, if necessary, a high-intensity conflict. To be clear, this is not just a resourcing issue. Service members will soon be operating both legacy and replacement systems concurrently—a challenge the U.S. Air Force and Navy have not encountered for decades. Managing these issues requires leadership and careful attention from the highest levels—a commodity that is often in short supply.

Unfortunately, these are far from the only challenges the United States and its allies will have to contend with in 2024. Washington will also have to manage the growing proxy war with Iran and ongoing concerns about its nuclear program, as well as a host of other nonproliferation challenges.

Thinking about the unthinkable in 2024 does not mean reviving Strangelovian concepts from the Cold War. Instead, it is about being realistic about the potential for direct conflicts with Russia, China, or North Korea and wrestling with a more difficult and uncomfortable question: If the United States goes to war, is it prepared to manage nuclear coercion and respond to potential nuclear use?

Kelsey Hartigan is deputy director of the Project on Nuclear Issues and senior fellow with the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.

Commentary is produced by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a private, tax-exempt institution focusing on international public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan and nonproprietary. CSIS does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2024 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. All rights reserved.

Kelsey Hartigan

Programs & projects.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Nuclear weapons and international conflict: theories and empirical evidence.

- Daniel S. Geller Daniel S. Geller Daniel S. Geller is Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at Wayne State University. He conducts research and teaches in the areas of International Politics, Defense Policy, and Foreign Policy. From 2000 through 2010 Dr. Geller served as a consultant to the U.S. Department of State, Office of Technology and Assessments, and in 2009 he was a member of a Senior Advisory Group to the U.S. Strategic Command on the Nuclear Posture Review. Dr. Geller was a Co-Principal Investigator on an NSF grant involving the expansion of the militarized interstate dispute database. He has published extensively in books, journals and edited collections on the subject of interstate war. His most recent books are Nations at War: A Scientific Study of International Conflict (Cambridge University Press) co-authored with J. David Singer and The Construction and Cumulation of Knowledge in International Relations (Blackwell, Ltd.) co-edited with John A. Vasquez.

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.347

- Published online: 27 July 2017

The balance of conventional military capabilities is intrinsic to understanding patterns of war among nations. However, cumulative knowledge relating to the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict interaction is largely absent. Framework is provided for analyzing the results of quantitative empirical research on this question and to identify any extant strong and consistent patterns in the interactions of states that can be associated with the possession of nuclear weapons.

Since 1945, a vast, sophisticated, and contradictory literature has developed on the implications of nuclear weaponry for patterns of international conflict and war. This theoretical and empirical work has principally focused on the conflict effects of these weapons for the interaction of nuclear-armed states, although a growing number of studies have explored the impact of a state’s possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nonnuclear opponents. Given the destructive capacity of these weapons and their questionable value for battlefield use, most of this work has concentrated on the requirements for successful deterrence. In categorizing the studies, some scholars note that “classical deterrence theory” derives from the Realist paradigm of international politics and subdivide this theory into two complementary strands: structural (or neorealist) deterrence theory and decision-theoretic deterrence theory. In contrast, other analysts choose to classify work on nuclear deterrence into three schools of thought: nuclear irrelevance; risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war; and the nuclear revolution. The essence of these divisions involves a debate about what the possession of nuclear weapons does for a state that controls them. Does the possession of these weapons affect the behavior of nuclear and nonnuclear opponents in disputes over contested values? Do the weapons impart political influence and hold military utility, or are they useless as tools for deterrence, compellence, or war?

- nuclear weapons

- crisis escalation

- nuclear war

- international conflict

- empirical international relations theory

Introduction

The balance of conventional military capabilities is intrinsic to understanding patterns of war among nations (Geller, 2000a ). However, cumulative knowledge relating to the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict interaction is largely absent. This article seeks to provide a framework for analyzing the results of quantitative empirical research on this question and to identify any extant strong and consistent patterns in the interactions of states that can be associated with the possession of nuclear weapons.

Since 1945 , a vast, sophisticated, and contradictory literature has developed on the implications of nuclear weaponry for patterns of international conflict and war. 1 This theoretical and empirical work has principally focused on the conflict effects of these weapons for the interaction of nuclear-armed states, although a growing number of studies have explored the impact of a state’s possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nonnuclear opponents. Given the destructive capacity of these weapons and their questionable value for battlefield use, most of this work has concentrated on the requirements for successful deterrence. In categorizing the studies, Zagare and Kilgour ( 2000 ), for example, note that “classical deterrence theory” derives from the Realist paradigm of international politics, and they subdivide this theory into two complementary strands: structural (or neorealist) deterrence theory and decision-theoretic deterrence theory. In contrast, Jervis ( 1979 , 1984 , 1988 ), among others, chooses to classify work on nuclear deterrence into three schools of thought: nuclear irrelevance; risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war; and the nuclear revolution. The essence of these divisions involves a debate about what the possession of nuclear weapons does for a state that controls them. Does the possession of these weapons affect the behavior of nuclear and non-nuclear opponents in disputes over contested values? Do the weapons impart political influence and hold military utility or are they useless as tools for deterrence, compellence, or war?

Nuclear strategy has principally concerned itself with the efficacy of nuclear weapons as a deterrent. One school of thought—nuclear revolution theory—characterized by the works of Brodie ( 1946 , 1959 , 1978 ), Waltz ( 1981 , 1990 , 1993 , 2003 ), and Jervis ( 1984 , 1988 , 1989a ), holds that the incredibly rapid and destructive effects of nuclear weapons creates a strong disincentive for nuclear-armed states to engage each other in disputes that might escalate to the level of war. The “nuclear revolution” means that nuclear weapons can deter aggression at all levels of violence and makes confrontations and crises between nuclear-armed states rare events. The maintenance of a nuclear second-strike capability is all that is required for a successful military deterrent force.

A second school of thought—risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war—emphasizes the problem of “risk” in confrontations between states in possession of nuclear weapons. The issue here is that, in disputes between nuclear-armed states, the use of nuclear weapons carries such enormous costs for both sides that any threat to use the weapons lacks inherent credibility. While allowing that a nuclear second-strike capability can deter a full-scale nuclear strike by an opponent, these analysts argue that states will manipulate the risk of dispute escalation and war for the purposes of deterrence and compellence (e.g., Gray, 1979 ; Kahn, 1962 , 1965 ; Schelling, 1960 , 1966 ). In this view, crises and brinkmanship tactics become surrogates for war in confrontations between nations in possession of nuclear weapons (Snyder & Diesing, 1977 ). Associated with this thesis is the concept of the “stability-instability paradox” (Snyder, 1965 ), whereby nuclear-armed states are secure in the deterrence of general nuclear war but are free to exploit military asymmetries (including strategic and tactical nuclear asymmetries as well as conventional military advantages) at lower levels of violence (e.g., Kissinger, 1957 ).

Yet another perspective holds nuclear weapons to be “irrelevant” as special instruments of either statecraft or war (Mueller 1988 , 1989 ). 2 In this argument, nuclear weapons are not substantially different in their deterrent effect from conventional military forces and, in John Mueller’s view, developed nations will not engage each other in either conventional or nuclear wars—having already witnessed the devastation that can be produced with both types of weaponry. A related argument holds that the possession of nuclear weapons provides little or no coercive advantage in confrontations with either nuclear-armed or nonnuclear states. A number of quantitative empirical studies of deterrence failures and successes (in both direct- and extended-deterrence cases) have produced results supportive of this thesis. Additionally, a notable formal mathematical study of deterrence by Zagare and Kilgour ( 2000 ) demonstrates that raising the costs of war above a certain threshold has no effect on deterrence stability. In this work, Zagare and Kilgour also maintain that, while nuclear weapons may increase the costs associated with a deterrent threat, they simultaneously decrease the credibility of the threat—and hence the stability of deterrence. These contrary effects serve to minimize the impact of nuclear weapons on effective deterrence. In short, nuclear and nonnuclear crises should exhibit the same patterns of escalation.

Over the past 35 years, large-scale quantitative empirical studies have attempted to generate evidence relating to these theories. Discussion of some of these works follows.

Nuclear Weapons and Patterns of International Conflict

The nuclear revolution.

The term “nuclear revolution” was coined by Robert Jervis ( 1989a , ch. 1), although the initial recognition of the alterations in patterns of international politics likely to be wrought by nuclear weapons should be credited to Bernard Brodie ( 1946 ). As Jervis has noted:

the changes nuclear weapons have produced in world politics constitute a true revolution in the relationships between force and foreign policy. The fact that neither [the United States nor the Soviet Union] can protect itself without the other’s cooperation drastically alters the way in which force can be used or threatened . . . The result is to render much of our prenuclear logic inadequate. As Bernard Brodie has stressed, the first question to ask about a war is what the political goal is that justifies the military cost. When the cost is likely to be very high, only the most valuable goals are worth pursuing by military means . . . What prospective . . . goals could possibly justify the risk of total destruction? (Jervis, 1989a , p. 13, 24)

Moreover, for Jervis ( 1989b ), that this destruction was essentially unavoidable under any plausible strategy constituted the essence of the nuclear revolution. Jervis ( 1989a , pp. 23–25) went on to enumerate changes in international politics directly attributable to the presence of nuclear weaponry, including the absence of war among the great powers, the declining frequency of great power crises, and the tenuous link between the conventional or nuclear balance among great powers and the political outcomes of their disputes. 3

Kenneth Waltz ( 1981 , 1990 , 1993 , 2003 , 2008 ) has been exceptionally prominent in developing and forwarding the thesis that nuclear weapons are a force for peace and that nuclear proliferation will lead to declining frequencies of war. Waltz argues that nuclear weapons are simply more effective in dissuading states from engaging in war than are conventional weapons:

In a conventional world, states going to war can at once believe that they may win and that, should they lose, the price of defeat will be bearable (Waltz, 1990 , p. 743). A little reasoning leads to the conclusions that to fight nuclear wars is all but impossible and that to launch an offensive that might prompt nuclear retaliation is obvious folly. To reach these conclusions, complicated calculations are not required, only a little common sense (Waltz in Sagan & Waltz, 1995 , p. 113). The likelihood of war decreases as deterrent and defensive capabilities increase. Nuclear weapons make wars hard to start. These statements hold for small as for big nuclear powers. Because they do, the gradual spread of nuclear weapons is more to be welcomed than feared. (Waltz in Sagan & Waltz, 1995 , p. 45)

Given this logic, evidence consistent with an absence of war or the use of force short of war between nuclear-armed states and few (or a declining frequency of) crises between nuclear powers would be supportive of the nuclear revolution thesis.

Empirical Evidence

A number of quantitative empirical studies have produced evidence relevant to the nuclear revolution thesis. In an early study of the effects of nuclear weapons possession, Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ) present both a formal mathematical model and an empirical test of deterrence success. The model assumes the possibility of nuclear war (i.e., the use of nuclear weapons) when nuclear asymmetry exists (only one side possesses nuclear weapons), but assumes the absence of nuclear war among nuclear-armed states. The model indicates a rising probability of nuclear war resulting from nuclear proliferation to the midpoint of the international system, where half of the states possess nuclear weapons, at which point any further proliferation results in a declining probability of nuclear war. When all nations possess nuclear weapons, the probability of nuclear war is zero. The supporting empirical analysis uses early Correlates of War (COW) Project Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data, for the years 1945 through 1976 , for four classes of dyads: nuclear/nuclear, nuclear/nonnuclear with a nuclear ally, nuclear/nonnuclear, and nonnuclear/nonnuclear. The analysis examines the distribution of threats, interventions, and wars across the four dyad classes and indicates that the presence of a symmetric nuclear threat constrains conflict by reducing its likelihood of escalation to the level of war. The two classes of nuclear/nuclear and nuclear/nonnuclear with a nuclear ally have the highest probabilities of employing only threats and the lowest probabilities of engaging in interventions and wars. This evidence is consistent with the predictions of the nuclear revolution thesis. 4

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) provides a multivariate analysis of factors associated with both militarized interstate disputes and wars for all dyads between 1885 and 2000 (MID database). The data set used in his study contains 611,310 dyad years, and tests were performed on time sections from 1885–1944 and 1945–2000 . He reports that in symmetric nuclear dyads (both states possess nuclear weapons) the odds of war drop precipitously. Rauchhaus concludes that Waltz and other nuclear revolution theorists find support for their thesis in the patterns uncovered by his study.

Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) examine the relationship between the severity of violence in international crises and the number of states involved in the crises that possess nuclear weapons. Using data from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project for the years 1918 through 2000 , their results indicate that crises in which nuclear actors are involved are more likely to end without violence and that, as the number of nuclear-armed states engaged in crises increases, the probability of war decreases. This evidence is interpreted as supportive of the nuclear revolution thesis: the presence of nuclear weapon states in international crises has a violence-dampening effect due to the potential consequences of escalation and the use of nuclear force.

In a second study, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) hypothesize that nuclear weapons act as shields against aggressive behavior directed toward their possessors. Specifically, it is postulated that nuclear states will be constrained in engaging in aggressive actions toward other nuclear-armed powers. Data is drawn from the ICB Project for the years 1945 through 2000 , using directed dyads as the unit of analysis. The results indicate that nuclear opponents of other nuclear-armed powers are limited in their use of violent force. However, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a , p. 251) also note that the “restraining effect of nuclear weapons on violent aggression does not appear to affect the propensity for actors to engage each other in general crises, in contrast with the expectations of . . . the ‘nuclear revolution’ model. . .”

Additional results consistent with the nuclear revolution thesis are reported in a study by Sobek, Foster, and Robinson ( 2012 ). Using directed-dyad year with MID data for the period between 1945 and 2001 , the study examines the effects of efforts to develop nuclear weapons on the targeting of the proliferator in militarized disputes. Sobek et al. ( 2012 , p. 160) conclude that “. . .if a state . . . gains nuclear weapons, then the odds of being targeted in a militarized dispute falls.” States developing nuclear weapons are high-frequency targets in MIDs, but “. . .[t]argeting drops precipitously when [joint] acquisition is achieved” (Sobek et al., 2012 , p. 160).

However, Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) present evidence that is counter to the preceding studies. Using data collected by Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), they contend that nuclear dyads are neither more nor less likely to fight wars or engage in sub-war conflicts than are nonnuclear dyads. They argue that the evidence indicating a strong negative probability of war in symmetric nuclear dyads is due to the statistical model used by Rauchhaus, whereas the positive association for nuclear dyads and crisis frequency reported by Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) is due to selection effects (i.e., nuclear weapons possession is more a consequence rather than a cause of conflict).

The nuclear revolution thesis maintains that there should be a general absence of war or the use of force short of war among nuclear-armed states. In addition, there is the expectation of few (or a diminishing number of) crises in nuclear dyads, as the fear of escalation will exert a powerful constraint on aggressive behavior.

Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ) present compelling evidence that nuclear asymmetry or the absence of nuclear weapons on both sides of a conflict are more likely to be associated with war. In their data, between 1945 and 1976 , there were 17 cases of war between nonnuclear states, two cases of war in asymmetric nuclear dyads, and zero cases of war in either nuclear dyads or nuclear/nonnuclear dyads where the nonnuclear party had a nuclear-armed ally. Rauchhaus’s ( 2009 ) study also presents evidence that symmetric nuclear dyads are unlikely to engage in war. The article by Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) reports results consistent with those of Bueno de Mesquita and Riker ( 1982 ). Specifically, crises ending in war are not uncommon for confrontations engaging nonnuclear states and for confrontations in which only one state possesses nuclear weapons. However, as the number of nuclear participants increases beyond one, the probability of full-scale war diminishes. Only the results of Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) stand in contrast with the findings on symmetric nuclear dyads and the probability of war. Similarly, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) show findings consistent with the nuclear revolution thesis: symmetric nuclear dyads engage in few crises where violence is the “preeminent” form of interaction. This conclusion is also supported by the findings reported by Sobek et al. ( 2012 ). However, Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) and Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) also note that there appears to be no constraining effect produced by nuclear weapons on the occurrence of crises that exhibit lower levels of hostility in symmetric nuclear dyads.

Since the advent of nuclear weapons in 1945 , there has been one war between nuclear-armed powers: the Kargil War of 1999 involving India and Pakistan (Geller, 2005 , p. 101). This conflict remained at the conventional level and surpassed the threshold of 1,000 battle deaths set by the Correlates of War Project for classification as a war (Singer & Small, 1972 ; Small & Singer, 1982 ). However, Paul ( 2005 , p. 13) argues that, despite the conventional military asymmetry between India and Pakistan (in India’s favor) that existed at the time of the Kargil War, the development of Pakistani nuclear weapons actually permitted Pakistan to launch a conventional invasion of the disputed territory of Kashmir. As Paul explains, only in a long war could India mobilize its material superiority, but as a result of the development of Pakistani nuclear weapons, a long war becomes “inconceivable” without incurring the risk of nuclear escalation. Hence, Pakistan’s leaders were emboldened to initiate a conventional war behind the shield of their nuclear deterrent despite their conventional military inferiority. This sole case of conventional war between nuclear-armed states—and its facilitation by the risk of unacceptable escalation provided by nuclear weapons—stands in stark contradiction to the predictions of nuclear revolution theory. 5

These collective results provide only partial support for the nuclear revolution thesis. As the theory suggests, war between nuclear-armed states should be nonexistent or a very rare event. This prediction, to date (with one notable exception), has been upheld. However, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) report that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—in contradiction to the predictions of nuclear revolution theory. This is an empirical question that will receive additional examination in the following section.

Risk Manipulation, Escalation, and Limited War

A second school of thought—risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war—finds its archetypal expression in the seminal work of Henry Kissinger ( 1957 ). According to this thesis (and counter to that of nuclear revolution theory), the possession of a nuclear second-strike capability may deter a nuclear attack by an opponent on one’s home territory, but not much else. Kissinger argued that the United States (and its NATO allies) required the ability to conduct successful combat operations at levels of violence below that of general nuclear war if the protection of Europe against Soviet aggression was a political goal. Some years later, Snyder ( 1965 ) discussed this as what was later termed the “stability-instability paradox.” The essence of the paradox was that stability at the level of general nuclear war permitted the exploitation of military asymmetries at lower levels of violence—including strategic (counterforce) and tactical nuclear wars as well as conventional forms of combat. The thesis that strategic nuclear weapons possessed little political or military utility other than deterring a nuclear attack on one’s home territory led to a number of works devoted to the analysis of tactics for coercive bargaining and limited war by Thomas Schelling ( 1960 , 1966 ), Herman Kahn ( 1960 , 1962 , 1965 ), and others. 6

As Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 , p. 450) maintain, the primary effect of the possession of nuclear weapons on the behavior of nuclear adversaries is the creation of new constraints on the ultimate range of their coercive tactics—a result of the extraordinary increase in the interval between the value of the interests at stake in a conflict and the potential costs of war. They note that before the advent of nuclear weapons, this interval was comparatively small and states could more readily accept the risk of war in a coercive bargaining crisis or engage in war in order to avoid the loss of a contested value. In contradistinction, given even small numbers of nuclear weapons in the stockpiles of states, it is far more difficult to conceive of an issue worth incurring the high risk of nuclear war, much less the cost of actually fighting one. 7

According to this thesis, a direct result of the constraints created by the presence of nuclear weapons has been the attempt by nuclear powers to control, in a more finely calibrated manner, the threat and application of force in disputes with other nuclear-armed states. These developments find theoretical and empirical expression in the concept of escalation , which is defined as the sequential expansion of the scope or intensity of conflict (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 127, 188). 8 In most standard formulations, escalation is conceived as a generally “controllable and reversible process,” 9 which a rational decision maker can employ in conflict situations as an instrument of state policy (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 188). Decision makers estimate the relative bargaining power of the rivals and engage in increasingly coercive tactics that are designed to undermine the opponent’s resolve. Controlled escalation occurs when each side is capable of inflicting major or unacceptable damage on the other but avoids this while attempting to influence the opponent with measured increases in the conflict level that incorporate the threat of possible continued expansion.

The measured application of force and the ability to control escalation in nuclear disputes are seen—by these strategic theorists—as indispensable for securing political values while minimizing risk and cost (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , p. 137; Russett, 1988 , p. 284). A preeminent theorist in this school, Herman Kahn ( 1965 , p. 3), described escalation as “an increase in the level of conflict . . . [often assuming the form of] a competition in risk-taking or . . . resolve.” As this theory developed, conflict analysts elaborated the risks involved in the process and incorporated the manipulation of these risks as a possible tactic in one’s strategy. 10

Clearly, nuclear weapons have not altered the values at stake in interstate disputes (and the desire to avoid political loss), but rather have increased the rapid and immediate costs of war. As a result, in a severe conflict between nuclear powers, the decision maker’s dilemma is to construct a strategy to secure political interests through coercive actions that raise the possibility of war without pushing the risk to an intolerable level. Some analysts argue that the solution to this problem has entailed an increase in the “threshold of provocation,” providing greater area of coercive maneuver in the threat, display, and limited use of force (Osgood & Tucker, 1967 , pp. 144–145; Snyder & Diesing, 1977 , p. 451). Hostile interaction between nuclear powers under this higher provocation threshold can range from verbal threats and warnings, to military deployments and displays, to the use of force in limited wars. Hence, in disputes between nuclear powers, it is argued that military force should be viewed as requisite but “potentially catastrophic power” that must be carefully managed and controlled within the bounds of reciprocally recognized constraints (Osgood & Tucker 1967 , p. 137).

It is frequently stated that the principal exemplar of this new form of competition is the local crisis. Obviously, crises have an extensive history in international politics, but the argument is made that the nuclear age has produced an expansion of steps on the escalation ladder and has intensified the maneuvering of nuclear rivals for dominant position in conflicts below the level of all-out war. For example, Snyder and Diesing note that:

the expanded range of crisis tactics in the nuclear era can be linked to a new conception of crises as surrogates for war, rather than merely dangerous incidents that might lead to war. . . [S]ince war is no longer a plausible option between nuclear powers, they have turned to threats of force and the demonstrative use of force short of war as a means of getting their way. The winner of the encounter is the one who can appear the most resolved to take risks and stand up to risks. (Snyder & Diesing, 1977 , pp. 455–456)

Given this logic, conflicts between nuclear powers should reveal different escalatory patterns than conflicts between states where only one side possesses nuclear arms, or conflicts where neither side possesses nuclear arms. Specifically, disputes between nuclear powers should evidence a greater tendency to escalate—short of war—than nonnuclear disputes or disputes, in which only one side possesses a nuclear capability.

Kugler ( 1984 ) presents an empirical test of classical nuclear deterrence theory: the study examines whether nuclear weapons are salient in preventing the initiation or escalation of war to extreme levels. The analysis focuses on crisis interactions involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China (PRC) with the case set drawn from Butterworth ( 1976 ) and CACI (Mahoney & Clayberg, 1978 , 1979 ). The cases used in the analysis constitute 14 extreme crises where nuclear nations were involved and where nuclear weapons “played a central role” (Kugler, 1984 , p. 477). The results indicate that crises of extreme intensity diminish as the threat of nuclear devastation becomes mutual. In other words, as the capacity of actors to destroy each other with nuclear weapons increases, there is a tendency to decrease the intensity of conflict, and to settle those crises that reach extreme proportions by compromise. This suggests that deterrence of war through the symmetric possession of nuclear weapons is operative in the conflict dynamics of great-power crises.

As Siverson and Miller ( 1993 , pp. 86–87) note, the earliest systematic statistical work on the effect of nuclear weapons possession in the escalation of conflict is by Geller ( 1990 ). This study employs the Correlates of War (COW) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data covering 393 MIDs between 1946 and 1976 and uses the MID five-level dispute hostility index in coding the dependent variable. The results indicate that dispute escalation probabilities are significantly affected by the distribution of nuclear capabilities. Comparing the escalatory behavior of nuclear dyads with the escalatory behavior of nonnuclear dyads in militarized disputes, it is reported that symmetric nuclear disputes indicate a far greater tendency to escalate—short of war—than do disputes for nonnuclear pairs: disputes in which both parties possess nuclear weapons have approximately a seven times greater probability (0.238) of escalating of escalating than do disputes in which neither party possesses nuclear arms (0.032). The conclusion indicates that the presence of nuclear weapons impacts the crisis behavior of states, with disputes between nuclear states more likely to escalate, short of war, than disputes between nonnuclear nations.

Huth, Gelpi, and Bennett ( 1993 ) analyze 97 cases of great power deterrence encounters from 1816 to 1984 as a means of testing the explanatory power of two competing theoretical approaches to dispute escalation. Dispute escalation is defined as the failure of the deterrent policies of the defender. Deterrence failure occurs when the confrontation ends in either the large-scale use of force or defender capitulation to the challenger’s demands. For the post- 1945 period, the findings indicate that, for nuclear dyads, the possession of a nuclear second-strike capability by the defender substantially reduces the likelihood of the confrontation ending either in war or in capitulation by the defender. However, the possession of nuclear weapons in great power dyads does not deter the challenger from initiating militarized disputes.

Asal and Beardsley ( 2007 ) examine the relationship between the severity of violence in crises and the number of states involved in the confrontations that possess nuclear weapons. Using data from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project, the study includes 434 international crises extending from 1918 through 2001 . The results indicate that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—and that “crises involving nuclear actors are more likely to end without violence. . . [A]s the number of nuclear actors increases, the likelihood of war continues to fall” (Asal & Beardsley, 2007 , p. 140). The authors also note that their results indicate that there may be competing effects within nuclear dyads: specifically, that both sides will avoid war but engage in sub-war levels of escalatory behavior (Asal & Beardsley 2007 , p. 150, fn. 6).

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) also attempts to test the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict behavior. The data are generated using the EUGene (v.3.203) statistical package for dyad years from 1885 through 2000 and for a subset period from 1946 through 2000 . 11 The findings indicate that, in militarized disputes, symmetric nuclear dyads have a lower probability of war than do dyads where only one nation possesses nuclear arms. Moreover, in dyads where there are nuclear weapons available on both sides (nuclear pairs), the findings indicate that disputes are associated with higher probabilities of crises and the use of force (below the level of war). The author suggests that the results support the implications of Snyder’s ( 1965 ) stability-instability paradox. The results are also supportive of the Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 ) contention that crises have become surrogates for war between nuclear-armed states where the manipulation of risk through coercive tactics is employed to secure political objectives.

A study by Kroenig ( 2013 ) provides similar results. Using an original data set of 52 nuclear crisis dyads drawn from the International Crisis Behavior Project for the years 1945 through 2001 , Kroenig codes the outcomes of nuclear crises against nuclear arsenal size and delivery vehicles, and the balance of political stakes in the crisis. He concludes “. . . that nuclear crises are competitions in risk taking, but that nuclear superiority—defined as an advantage in the size of a state’s nuclear arsenal relative to that of its opponent—increases the level of risk that a state is willing to run” (Kroenig, 2013 , p. 143), and hence its probability of winning the dispute without violence. These results support the contention that crises between nuclear-armed states tend to involve dangerous tactics of brinkmanship and tests of resolve.

Evidence consistent with the risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war thesis would include the presence of severe crises between nuclear powers that exhibit escalatory behavior short of unconstrained war but inclusive of the use of force. The limited conventional war of 1999 between India and Pakistan, initiated and carried out by Pakistan under the umbrella of its nuclear deterrent, is an extreme example of precisely this type of conflict interaction. It captures the logic of Snyder’s stability-instability paradox and incorporates, as well, descriptions by Schelling and by Kahn of the use of limited war (with the risk of greater violence to follow) as a means of persuading an adversary to relinquish a contested value.

Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) report that symmetric nuclear dyads engage in an unexpectedly large number of crises—a finding that is consistent with the Snyder and Diesing ( 1977 ) contention that crises have become surrogates for war among nuclear-armed states. Similarly, Huth, Bennett, and Gelpi ( 1992 ) note that, in great-power dyads, the possession of nuclear weapons by the defender does not deter dispute initiation by a nuclear-armed challenger, and that an outcome of either war or capitulation by the defender is unlikely. In findings not inconsistent with those of Huth et al., ( 1992 ), Kugler ( 1984 ) reports that (between 1946 and 1981 ), as the capacity of nuclear actors to destroy each other increases, there is a tendency to decrease the intensity of the conflict. Both Geller ( 1990 ) and Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), in large-scale quantitative empirical analyses of escalation patterns in nuclear, nonnuclear, and mixed (asymmetric) dyads, report that symmetric nuclear dyads are substantially more likely to escalate dispute hostility levels—short of war—than are nonnuclear pairs of states. In Geller’s study, the findings indicate that disputes in which both parties possessed nuclear weapons had approximately a seven times greater probability of escalation (0.238) than did disputes in which neither party possessed nuclear arms (0.032). Last, Kroenig ( 2013 ) demonstrates that confrontations between nuclear-armed states may be understood as competitions in risk taking and that an advantage in the size of one’s nuclear arsenal is associated with increased levels of risk acceptance and, hence, successful coercion.

These cumulative findings are strongly supportive of the risk manipulation, escalation, and limited war thesis on the effects of symmetric nuclear weapons possession. 12 Moreover, the case of the 1999 limited conventional war between India and Pakistan reflects both the logic of this school of thought as well as the patterns of escalation described in the large-scale quantitative studies of militarized disputes between nuclear-armed states.

Nuclear Irrelevance

The views of John Mueller are most commonly associated with the thesis of “nuclear irrelevance.” Mueller ( 1988 , 1989 ) makes the highly controversial argument that nuclear weapons neither defined the stability of the post-Second World War U.S.-Soviet relationship nor prevented a war between the superpowers; he also maintains that the weapons did not determine alliance patterns or induce caution in U.S.-Soviet crisis behavior. His contention is that the postwar world would have developed in the same manner even if nuclear weapons did not exist.

Mueller’s logic allows that a nuclear war would be catastrophic, but that nuclear weapons simply reinforced a military reality that had been made all too clear by World War II: even conventional war between great powers is too destructive to serve any conceivable political purpose. Moreover, the satisfaction with the status quo shared by the United States and the Soviet Union removed any desire for territorial conquest that might have led to conflict, as each superpower held dominance in its respective sphere of influence. Similarly, provocative crisis behavior was restrained by the fear of escalation—and although the presence of nuclear weapons may have embellished such caution, the mere possibility of fighting another conventional war such as World War II would have induced fear and restraint on the part of decision makers. In short, nuclear weapons may have enhanced Cold War stability, but their absence would not have produced a different world. Mueller closes his argument with the extrapolation that war among developed nations is obsolescent. It may simply be that, in the developed world, a conviction has grown that war among post-industrial states “would be intolerably costly, unwise, futile, and debased” (Mueller, 1988 , p. 78). In this sense, nuclear weapons lack deterrent value among developed states because—absent the incentive for war—there is nothing to deter.

In a related thesis, Vasquez ( 1991 ) holds that it is unlikely—given what is known about the complex conjunction of multiple factors in the steps to war—that any single factor, such as the availability of nuclear weapons, causes or prevents wars. He makes the nuanced argument, in discussing the long post-war peace between the United States and the Soviet Union, that:

There is little evidence to support the claim that nuclear deterrence has prevented nuclear war or that it could do so in the future, if severely tested . . . Nuclear war may have been prevented not because of deterrence, but because those factors pushing the United States and the USSR toward war have not been sufficiently great to override the risks and costs of total war (Vasquez, 1991 , p. 207, 214).

Of principal significance to Vasquez is the absence of a direct territorial dispute between the superpowers. Other factors that Vasquez believes contributed to the long peace include satisfaction with the status quo, the experience of the two world wars, the establishment of rules and norms of interaction between the superpowers, procedures for crisis management, and effective arms control regimes. 13

A second area of application for the nuclear irrelevancy thesis involves asymmetric dyads. Little has been written about the effects of nuclear weapons on the patterns of serious disputes where this technology is possessed by only one side. However, what has been written suggests that in these types of conflicts nuclear weaponry may lack both military and psychological salience. For example, Osgood and Tucker ( 1967 , p. 158) and Blainey ( 1973 , p. 201) argue that tactical nuclear weapons are largely devoid of military significance in either Third World conflicts or insurgencies, where suitable targets for the weapons are absent. An additional disincentive to the use of nuclear weapons against a nonnuclear opponent is that it might be expected to increase the pressures for nuclear proliferation and to incite international criticism and denunciation of the nuclear state (Huth, 1988a , p. 428). It also has been suggested that a sense of fairness or proportionality contributes a moral aspect to the practical military and political inhibitions on using nuclear weapons against a nonnuclear opponent and that the set of these concerns has undermined the efficacy of nuclear power as a deterrent in asymmetric conflicts (Huth & Russett, 1988 , p. 38; Russett, 1989 , p. 184).

Moreover, Waltz ( 1967 , p. 222) and Osgood and Tucker ( 1967 , pp. 162–163) caution against exaggerating the differences due to nuclear weapons between contemporary and historical major power-minor power conflicts. Long before the advent of nuclear weapons, minor powers frequently defied or withstood great power pressure as a result of circumstances of geography, alliance, or an intensity of interests that the major power could not match.

In a similar argument, Jervis ( 1984 , p. 132) examines the logic of escalation in a losing cause (presumably a tactic relating directly to disputes between nuclear and nonnuclear states) and suggests that a threat to fight a war that almost certainly would be lost may not be without credibility—indeed, there may be compelling reasons for actually engaging in such a conflict. Specifically, if the cost of winning the war is higher to the major power than is the value at stake in the dispute, then the confrontation embodies the game structure of “Chicken.” Hence, even if war is more damaging to the minor power than to the major power, the stronger may still prefer capitulation or a compromise solution to the confrontation rather than engaging in the fight. In sum, Jervis ( 1984 , p. 135) argues that: “the ability to tolerate and raise the level of risk is not closely tied to military superiority . . . The links between military power—both local and global—and states' behavior in crises are thus tenuous.”

The third area of application for the nuclear irrelevancy thesis involves policies of extended deterrence. The efficacy of nuclear weapons for the purposes of extended deterrence was an issue of immense importance throughout the Cold War. In fact, the positions on whether American strategic nuclear weapons were sufficient to deter a Soviet-Warsaw Pact invasion of Western Europe or whether substantial conventional and tactical nuclear weapons were necessary for successful deterrence constituted a continuing debate for decades. Nuclear revolution theory contended that the U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal (with its ability to destroy the Soviet Union) was sufficient to induce caution and restraint on the part of the Soviet leadership. However, the strategists who formulated the stability-instability paradox argued that U.S. strategic nuclear weapons would deter a direct nuclear strike on the United States itself, but little else. According to this logic, for the successful extended deterrence of an attack on Europe, the United States and NATO required effective combat forces that could fight at the level of conventional war and even war with tactical nuclear weapons. Escalation dominance was required to sustain extended deterrence. Of course, extended deterrence policies existed long before the development of nuclear weapons and applied to any situation where a powerful defender attempted to deter an attack against an ally by threat of military response. The issue at hand is the effectiveness of a strategic nuclear threat in sustaining a successful extended deterrence policy. The nuclear irrelevancy position is that such weapons lack significance in extended deterrence situations.

In sum, the nuclear irrelevance thesis suggests that nuclear weapons have little salience in the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed dyads. Evidence consistent with this position would indicate that, for symmetric dyads, the possession of nuclear weapons or the nuclear balance does not affect crisis escalation, crisis outcomes, or dispute initiation patterns. In addition, if a set of practical, political, and ethical constraints has weakened the military advantage of possessing nuclear weapons in a serious dispute with a nonnuclear state, then the monopolization of a nuclear capability will not confer a bargaining edge to the nuclear-armed state in an asymmetric crisis. The nuclear irrelevance school would also gain support in findings indicating the absence of substantive effects resulting from possession of nuclear weapons in extended deterrence situations.

In evaluating the empirical evidence regarding the nuclear irrelevance thesis, it is useful analytically to separate the studies into distinct categories: (a) findings involving the effects of nuclear weapons in nuclear-armed dyads; (b) findings involving the interaction patterns of nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents; and (c) findings bearing on extended deterrence situations.

(a) Nuclear dyads . The examination of evidence relating to nuclear revolution theory upheld the prediction that, as the theory suggests, war between nuclear-armed states should be nonexistent or a very rare event (e.g., Asal & Beardsley, 2007 ; Bueno de Mesquita & Riker, 1982 ; Rauchhaus, 2009 ). The success of this prediction (with the exception of the 1999 Kargil War) serves as the principal finding in support of the nuclear revolution thesis. However, this finding holds negative implications for the validity of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis. In other findings counter to the patterns hypothesized by the nuclear irrelevancy thesis, Geller ( 1990 ) reports results that indicate that the distribution of nuclear capabilities affects the patterns of escalation in militarized interstate disputes, and that symmetric nuclear dyads show substantially higher dispute escalation probabilities, short of war, than do nonnuclear dyads. Rauchhaus’s ( 2009 ) findings mirror Geller’s. Similarly, Beardsley and Asal ( 2009a ) note that the crisis behavior of symmetric nuclear dyads differs from that of asymmetric dyads. Only the work of Bell and Miller ( 2015 ) stands in opposition to this general pattern. Using data from Rauchhaus ( 2009 ), Bell and Miller ( 2015 , p. 83) contend that nuclear dyads do not exhibit conflict patterns distinct from nonnuclear dyads either in terms of war or sub-war militarized disputes.

However, other evidence relating to conflict behavior, crisis interaction patterns, or crisis outcomes that indicate that nuclear weapons were inconsequential in the disputes would support the contention that nuclear forces are irrelevant in symmetric dyads. For example, Blechman and Kaplan ( 1978 ) provide an empirical analysis of 215 incidents between 1946 and 1975 , in which the United States used its armed forces for political objectives. Their findings indicate that the strategic nuclear weapons balance between the United States and the Soviet Union did not influence the outcome of competitive incidents involving the two states (Blechman & Kaplan, 1978 , pp. 127–129). Instead, the authors maintain that the local balance of conventional military power was more important in determining the outcomes of the confrontations (Blechman & Kaplan, 1978 , p. 527).

Kugler ( 1984 ) presents an empirical test of nuclear deterrence theory by examining whether nuclear weapons are efficacious in preventing the initiation or escalation of crises to the level of war. The case set is 14 extreme crises between 1946 and 1981 involving the United States, the Soviet Union, and China. Of the 14 crises, five involved nuclear-armed dyads (a nuclear power on each side). He concludes that: “nuclear nations do not have an obvious and direct advantage over other nuclear . . . nations in extreme crises. Rather, conventional [military] capabilities are the best predictor of outcome of extreme crises regardless of their severity” (Kugler, 1984 , p.501).

In contrast to the findings by Blechman and Kaplan ( 1978 ) and Kugler ( 1984 ), a study by Kroenig ( 2013 ) provides different results. Using a data set of 52 nuclear crisis dyads ( 1945–2001 ) drawn from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project, Kroenig codes the outcomes of nuclear crises, nuclear arsenal size and delivery vehicles, and the balance of political stakes in the crisis. He concludes that nuclear superiority—defined as an advantage in the size of a state’s nuclear arsenal relative to that of its opponent—increases the level of risk that a state is willing to run and hence its probability of winning the dispute without violence (Kroenig, 2013 , p. 143).

Huth et al. ( 1992 ) examine militarized dispute-initiation patterns among great power rivalries between 1816 and 1975 as a means of testing a set of explanatory variables drawn from multiple levels of analysis. The principal focus of the study is to investigate the relationship between the structure of the international system and the initiation of great power disputes. However, the analysis does include a variable coded for the possession of nuclear weapons by the challenger’s rival. The findings indicate that the presence of defenders’ nuclear weapons does not deter challengers from initiating militarized disputes among great powers (Huth et al., 1992 , p. 478, 513).

Gartzke and Jo ( 2009 ) examine the effects of nuclear weapons possession on patterns of militarized dispute initiation using a sophisticated multivariate model and data drawn from the COW/MID database for directed dyads over the years 1946 through 2001 . Their findings indicate that nuclear weapons possession has little effect on dispute initiation behavior. The authors note that: “Instead, countries with security problems, greater interest in international affairs, or significant military capabilities are simultaneously more likely to fight and proliferate” (Gartzke & Jo, 2009 , p. 221). The relationship between nuclear weapons and MID initiation is rejected statistically: this finding applies to both symmetric (nuclear) and asymmetric (nuclear/nonnuclear) dyads.

(b) Asymmetric dyads . The nuclear irrelevancy school also maintains that the possession of nuclear weapons confers no bargaining advantage on the nuclear-armed power engaged in a confrontation with a nonnuclear state.

In a seminal study examining the effects of nuclear weapons on conflict interaction patterns, Organski and Kugler ( 1980 , pp. 163–164) identify 14 deterrence cases that occurred between 1945 and 1979 in which nuclear weapons could have been used. Seven of these cases involved a nuclear power in confrontation with a nonnuclear state (or a state with an ineffective nuclear force ). Their findings indicate that in only one case out of the seven did the nuclear-armed state win: “Nonnuclear powers defied, attacked, and defeated nuclear powers and got away with it” (Organski & Kugler, 1980 , p. 176). In the six cases that the nuclear power lost to a nonnuclear state, the winner was estimated to have conventional military superiority at the site of the confrontation (Organski & Kugler, 1980 , p. 177).

In a related study, Kugler ( 1984 ) isolates 14 cases of extreme crisis that occurred between 1946 and 1981 , in which nuclear weapons were available to at least one party in the dispute. Of these 14 cases, nine involved confrontations in which only one state had access to nuclear arms. In all nine cases, the outcomes of the crises favored the nonnuclear challenger. Once again, the balance of conventional military capabilities—not nuclear weaponry—provided the best predictor of crisis outcome (Kugler, 1984 , p. 501).

In an early large-scale study, Geller ( 1990 ) examines conflict escalation patterns in serious interstate disputes among nations with both symmetric and asymmetric types of weapons technology. This study employs the Correlates of War (COW) Militarized Interstate Dispute (MID) data, inclusive of 393 MIDs between 1946 and 1976 , and uses the MID five-level dispute hostility index in coding the dependent variable. The findings indicate that, for asymmetric dyads (with only one state in possession of nuclear arms), the availability of nuclear force has no evident inhibitory effect on the escalation propensities of nonnuclear opponents. In fact, the findings show that in this class of confrontation, both nonnuclear dispute initiators and targets act more aggressively than do their nuclear-armed opponents. The summation suggests that in confrontations between nuclear and nonnuclear states, war is a distinct possibility, with aggressive escalation by the nonnuclear power probable. In such cases, it is concluded that the conventional military balance may be determinative of the outcome (Geller, 1990 , p. 307).

In two studies published in 1994 and 1995 , Paul employs the case study method to examine the dynamics of asymmetric war initiation by weaker powers. Paul ( 1994 ) analyzes six cases of war initiation by weaker states against stronger states: three of these cases (China/U.S. in 1950 ; Egypt/Israel in 1973 ; and Argentina/Great Britain in 1982 ) involve nonnuclear nations initiating wars against nuclear-armed opponents. Paul ( 1994 , p. 173) concludes that nuclear weapons appear to have limited utility in averting war in asymmetric dyads. He notes that, with either nuclear or conventional weapons, a significant military advantage may be insufficient to deter a weaker state that is highly motivated to change the status quo. In a more focused study, Paul ( 1995 ) discusses the possible reasons underlying the nonuse of nuclear weapons by nuclear-armed states against nonnuclear opponents. Here he analyzes two cases (Argentina/Great Britain in the Falklands War of 1982 and Egypt/Israel in the Middle East War of 1973 ) in which nonnuclear states initiated wars against nuclear opponents. Paul argues that in both cases nuclear retaliation by the targets was deemed highly improbable by the nonnuclear war initiators due to a combination of limited war goals and taboos (unwritten and uncodified prohibitionary norms) against the use of nuclear weapons.

Rauchhaus ( 2009 ) attempts to test the effects of nuclear weapons possession on conflict behavior for asymmetric as well as for symmetric dyads using data generated by the EUGene (v.3.203) statistical program for dyad years from 1885 through 2000 . The findings indicate that, for asymmetric (nuclear/nonnuclear) dyads (in comparison to symmetric dyads), there is a higher probability of war. Asymmetric dyads are also more likely to be involved in militarized disputes that reach the level of the use of force (Rauchhaus, 2009 , pp. 269–270). In short, the study produces results that hold in opposition to the view that conflict between nuclear and nonnuclear states will be limited. As Rauchhaus ( 2009 , p. 271) concludes: “nuclear asymmetry is generally associated with a higher chance of crises, uses of force, fatalities, and war.”

A study by Beardsley and Asal ( 2009b ) produces findings that stand in counterpoint to the main body of analyses on conflict in asymmetric dyads. This work examines the question of whether the possession of nuclear weapons affects the probability of prevailing in a crisis. The data are drawn from the International Crisis Behavior (ICB) Project for directed dyads covering the years between 1945 and 2002 . The findings indicate that the possession of nuclear weapons provides bargaining leverage against nonnuclear opponents in crises: nuclear actors are more likely to prevail when facing a nonnuclear state (Beardsley & Asal, 2009b , p. 278, 289).

However, with regard to bargaining advantages that may be derived from the possession of nuclear weapons, Sechser and Fuhrmann ( 2013 ) argue (counter to Beardsley & Asal) that compellent threats based on nuclear force may lack credibility due to their indiscriminately destructive effects and the reputational costs that, presumably, would be associated with their use. Drawing on a new data set (Militarized Compellent Threats) containing 242 challenger-target dyads for the period 1918 to 2001 , they report findings indicating that “states possessing nuclear weapons are not more likely to make successful compellent threats [than nonnuclear states] . . . and that nuclear weapons carry little weight as tools of compellence” (Sechser & Fuhrmann, 2013 , p. 174).

An interesting corollary finding is presented by Narang ( 2013 ). Using data collected by Bennett and Stam ( 2004 ) to explore the conflict behavior of regional (non-superpower) nuclear actors from 1945 through 2001 , Narang finds little evidence supporting an existential deterrent effect for nuclear weapons against nonnuclear opponents. Rather, he concludes that the nuclear posture adopted by the nuclear-armed state is determinative of deterrence success, with an “asymmetric escalation” posture superior to either a “catalytic” or “assured destruction” posture in deterring conventional attacks with military force (Narang, 2013 , p. 280, 284–286).

(c) Extended deterrence . The logic of the nuclear irrelevancy thesis suggests that nuclear weapons should be of little salience in extended deterrence situations.

Huth defines deterrence as a policy that seeks to convince an adversary through threat of military retaliation that the costs of using military force outweigh any expected benefits. Extended deterrence is then defined by Huth ( 1988a , p. 424) as a confrontation between a defender and a potential attacker in which the defender threatens the use of military force against the potential attacker’s use of force against an ally (protégé) of the defender. There have been a large number of studies produced on the issue of the efficacy of extended nuclear deterrence—the majority of which report a body of consistent or complementary findings.

As noted in Harvey and James ( 1992 ), Bruce Russett’s ( 1963 ) analysis of 17 crises that occurred between 1935 and 1961 appears to be the first aggregate study of the factors associated with extended deterrence success and failure. Nine crisis cases involved defenders with a nuclear capability, and six of the nine cases resulted in successful extended deterrence. However, Russett draws no conclusions as to the independent effect of nuclear weapons on those outcomes. He does note that military equality on either the local (conventional) or strategic (nuclear) level appears to be a necessary condition for extended deterrence success.

Two studies published by Weede ( 1981 , 1983 ) also deal with the effectiveness of extended nuclear deterrence. Weede examines 299 dyads between 1962 and 1980 for evidence relating to patterns of extended deterrence success or failure. His findings are supportive of the position that nuclear weapons assist in producing extended deterrence success.