ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Analysis of misbehaviors and satisfaction with school in secondary education according to student gender and teaching competence.

- 1 Faculty of Education Sciences, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 2 Health Research Center, University of Almería, Almería, Spain

- 3 Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Autonomous University of Baja California, Ensenada, Mexico

- 4 Department of Didactic of Corporal Expression, Faculty of Education Sciences, Granada, Spain

Effective classroom management is a critical teaching skill and a key concern for educators. Disruptive behaviors disturb effective classroom management and can influence school satisfaction if the teacher does not have the competencies to control them. Two objectives were set in this work: to understand the differences that exist in school satisfaction, disruptive behaviors, and teaching competencies according to the gender of the students; and to analyze school satisfaction and disruptive student behaviors based on perceived teaching competence. A non-probabilistic and convenience sample selection process was employed, based on the subjects that we were able to access. 758 students participated (male = 45.8%) from seven public secondary schools in the Murcia Region (Spain). The age range was between 13 and 18 years ( M = 15.22; DT = 1.27). A questionnaire composed of the following scales was used: Competencies Evaluation Scale for Teachers in Physical Education, School Satisfaction and Disruptive Behaviors in Physical Education. Mixed Linear Models performed with the SPSS v.23 was used for statistical analyses. The results revealed statistically significant differences based on gender and physical education teaching competencies. In conclusion, the study highlights that physical education teacher skills influence disruptive behaviors in the classroom, and that this is also related to school satisfaction. Furthermore, it highlights that boys showed higher levels of negative behaviors than girls.

Introduction

Undisciplined behaviors in the classroom are a serious problem for the teaching and learning process during adolescence ( Medina and Reverte, 2019 ), and may have an impact on feelings regarding school satisfaction, the relationship with teachers or even on school failure ( Baños et al., 2017 ). These types of behaviors commonly occur in the Physical Education (PE) class, producing conflictive situations between peers (students) and even with the teacher himself/herself. It is therefore advisable to solve the problem in a rapid and effective fashion ( Müller et al., 2018 ). Faced with these situations, the competencies of the PE teaching staff play an important role ( Baños et al., 2017 ; Trigueros and Navarro, 2019 ; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2020 ); the way in which teachers design, organize and control their sessions can affect the students’ disruptive behaviors and class outcome.

As evidenced in research by authors such as Goyette et al. (2000) and Kulinna et al. (2006) , adolescents often show certain problematic behaviors in the classroom, such as idleness, disrespect, talking out of turn and/or avoiding or skipping classes, which have a negative impact on the learning environment. Even aggressive behaviors can sometimes arise in PE classes, such as bullying and peer fighting ( Weiss et al., 2008 ). Studies looking at inappropriate behaviors in PE have demonstrated that the students’ negative behavior not only affects the quality of teaching, but also interferes with peer learning ( Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Cothran et al., 2009 ). Moreover, disruptive behaviors are more common at the secondary school level than in primary education classes, as evidenced by various works (e.g., Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ). Adolescence, in particular, is characterized by a rebellious, non-conformist stage, a fight against authority, irresponsibility and low personal self-control. At this age, a disengagement with the school can occur, with a decreased willingness to comply with the rules and with expected behavior ( Fredericks et al., 2004 ).

In addition, gender has been used to analyze these behaviors, both in students and in teachers. Specifically, the female gender (both teachers and students) are those who report the highest incidence of inappropriate behaviors ( Kulinna et al., 2006 ), with females being the ones likely to receive this negativity ( Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ). There are several studies that have found higher levels of inappropriate behaviors among boys than among girls ( Beaman et al., 2006 ; Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ; Driessen, 2011 ). Boys tend to be more boisterous and disruptive with their peers ( Glock and Kleen, 2017 ) whereas girls tend to be more proactive and less problematic ( Driessen, 2011 ), albeit with more shy and introverted behaviors ( Glock and Kleen, 2017 ). Furthermore, boys are often more influenced by their peers than girls are, resulting in higher levels of truancy, punishments and challenging behaviors that teachers have to face ( Hadjar and Buchmann, 2016 ; Geven et al., 2017 ). Other authors (i.e., Baños et al., 2018 ) found that students claimed to have more aggressive behaviors during PE sessions.

Among the attributions made by the students regarding inappropriate behaviors when doing PE, the boredom they experience stands out, finding the classes monotonous, as well as expressing a certain discontent with the teacher. However, it should be noted that these are students with usually disruptive behaviors ( Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ). In relation to the teachers, some recent studies have linked disruptive behaviors to teacher competence as perceived by the students ( Baños et al., 2019 ; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2019 ; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2020 ). This research related the high levels of teaching competencies with low levels of negative behavior in PE classes although the study did not cover the effect of the teaching staff’s competence.

In addition, the scientific literature has stated that school satisfaction reduces student misbehavior, making it advisable to develop social and emotional skills, cognitive ability, behavioral and moral competencies, the recognition of positive behavior, belief in the future and prosocial norms ( Sun, 2016 ). In contrast, ineffective classroom management causes disarray and interruptions produced by a few adolescents, affecting both the anxiety and stress of their peers and that of the teachers ( Cothran et al., 2009 ).

In this way, the work of PE teachers plays a relevant part in developing good classroom behaviors. Depending on the skills that the teachers develop, they may increase or decrease negative behaviors ( Rasmussen et al., 2014 ). Thus, teachers who have a wide repertoire of teaching styles, and who know how to adapt them to different environments and learning content, manage to improve the students’ satisfaction with the school ( Invernizzi et al., 2019 ); this is also influenced by the orientations toward learning ( Agbuga et al., 2010 ).

Regarding the study of satisfaction, Diener’s theory of subjective well-being ( Diener, 2009 ) could be of great help. This theory consists of two dimensions, the cognitive dimension and the affective dimension. The cognitive dimension relates to the evaluative judgments of global satisfaction with life and its specific areas, while the affective dimension is identified with emotions and attachments such as fun, boredom and concern ( Diener and Emmons, 1985 ). In this vein, Baena-Extremera and Granero-Gallegos (2015) highlight the importance of the student being satisfied and at ease in school. An adolescent who is satisfied with the school is associated with higher levels of life satisfaction ( Scharenberg, 2016 ), with an adequate school climate managed by the teacher ( Varela et al., 2018 ) and with better social relationships among his/her peers ( Persson et al., 2016 ). However, a student who gets bored at school decreases the efficiency of any learning style ( Ahmed et al., 2013 ). This is associated with higher school dropout rates ( Takakura et al., 2010 ), and with low teacher competencies ( Sun, 2016 ), which in turn relates to greater disruptive behavior ( Baños et al., 2019 ).

Scientific evidence has demonstrated the impact of negative behaviors and student satisfaction on both the learning and teaching processes. However, there is not enough literature that links the skills of the PE teacher with either student satisfaction with the school or with classroom misbehavior. Therefore, this work sets out two important objectives: (1) to understand the differences that exist in terms of school satisfaction, disruptive behaviors and teaching competencies according to the gender of the students; and (2) to analyze school satisfaction and disruptive student behaviors based on perceived teaching competence. From a review of the literature, the following hypotheses are made:

(1) There will be a significant and positive correlation between school satisfaction, disruptive student behaviors and the perceived competencies of the PE teacher; however, there will be a significant and negative correlation between boredom with school, disruptive student behaviors, and the perceived competencies of the PE teacher.

(2) Boys will show more negative behaviors than girls although girls will score higher in school satisfaction and in the perception of teaching competencies.

(3) Students who perceive that PE teachers are competent will show less disruptive behavior and greater school satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

The design of this cross-sectional study was observational and descriptive selecting a non-probabilistic convenience sample according to the people that could be accessed from public high schools located in areas of medium socioeconomic level (from Murcia and Cartagena cities). No educational center is included in the program of Teaching Compensatory, program that allocates specific, material and human resources to guarantee access, permanence and promotion in the educational system for socially disadvantaged students. A total of 758 students participated (males = 45.8%) from seven public secondary schools in the Murcia region of Spain (94% Spanish, Caucasian; 4% Arab origin; 1% East European, Caucasian; 1% South American). All students of these educational centers from 2 nd , 3 rd , 4 th of ESO and 1 st of Baccalaureate (PE is also subject compulsory) were requested to participate in this research. Incomplete answers due to errors or omissions in their responses (28) were dismissed for analysis and 34 students did not obtain parental consent to participate in this investigation. The age range was between 13 and 18 years ( M = 15.22; SD = 1.27); the average age for the boys was 15.2 ( SD = 1.29) and for the girls was 15.18 ( SD = 1.26). The distribution in terms of course levels was as follows: 45.3% at ESO 2 nd level; 20.1% at ESO 3 rd level; 27.2% at ESO 4 th level; and 7.5% in the 1 st year of Baccalaureate. As PE is a compulsory subject for all students of the 1 st year of Baccalaureate, these students were also included in this research. There were no statistically significant differences in gender × age between the included participants ( p = 0.501) (see Table 1 ).

Table 1. Distribution of the sample (n) according to Gender × Age ( p = 0.501).

Instruments

To carry out this investigation, the next instruments have been used.

Teaching Competence

The Spanish version of the Competencies Evaluation Scale for Teachers in Physical Education (ETCS-PE) by Baena-Extremera et al. (2015) was used, adapted from the original Evaluation of Teaching Competencies Scale by Catano and Harvey (2011) . It consists of eight items that measure the students’ perception of teacher effectiveness. A seven-point Likert scale ranging from low (1, 2), medium (3, 4, 5), and high (6, 7) was used for the responses. The internal consistency indices were: Cronbach alpha (α) = 0.86; composite reliability = 0.86; Average Variance Extracted (AVE) = 0.59.

School Satisfaction

The Spanish version of the Intrinsic Satisfaction Classroom Questionnaire (ISC) by Castillo et al. (2001) was used, adapted from the original Intrinsic Satisfaction Classroom Scale by Nicholls et al. (1985) , Nicholls (1989) , and Duda and Nicholls (1992) . It consists of eight items that measure the degree of school satisfaction using two subscales that measure satisfaction/fun (five items) and boredom with school (three items). For the responses, a Likert scale ranging from 1 ( totally disagree ) and 5 ( totally agree ) was used. The internal consistency indices were: satisfaction/fun α = 0.76, composite reliability = 0.76, AVE = 0.54; boredom , α = 0.70; Composite reliability = 0.72; AVE = 0.52.

Disruptive Behaviors in Physical Education

The Disruptive Conduct in Physical Education Questionnaire (CCDEF) by Granero-Gallegos and Baena-Extremera (2016) was used, which is the Spanish version of the original Physical Education Classroom Instrument (PECI) by Krech et al. (2010) . This version consists of 17 items that measure disruptive behaviors in PE students in five subscales: (a) Aggressive (2 items), (b) Low engagement or irresponsibility (4 items), (c) Fails to follow directions (4 items), (d) Distracts or disturbs others (4 items), and (e) Poor self-management (3 items). A five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ( never) to 5 ( always) was used for the responses. The internal consistency indices were: aggressive ,α = 0.58, composite reliability = 0.81, AVE = 0.54; low engagement or irresponsibility , α = 0.73, composite reliability = 0.84, AVE = 0.74; fails to follow directions , α = 0.77, composite reliability = 0.94, AVE = 0.65; distracts or disturbs others , α = 0.81, composite reliability = 0.92, AVE = 0.80; poor self-management , α = 0.84, composite reliability = 0.96, AVE = 0.92. Given the low index achieved by Cronbach’s alpha, and that the AGR subscale consists of only two items, this factor was ignored in the analyses performed.

Permission to carry out the work was obtained from the competent bodies, be they at the secondary schools or the university. Parents and adolescents were informed about the protocol and the study’s subject matter. Informed consent by both was an indispensable requirement to participate in the research. The tools measuring the different variables were administered in the classroom by the researchers themselves, without the teacher present. All participants were informed of the study objective, the voluntary and confidential nature of the responses and the data handling, as well as their rights as participants under the Helsinki Declaration (2008) . This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia (REF-45-20/01/2016).

The questionnaires where completed in the classroom in about 25–30 min with the same researcher always present who expressed the possibility of consulting him about any doubts during the process, respecting the Helsinki Declaration (2008) .

Data Analysis

The descriptive statistics of the items, the correlations and the internal consistency of each subscale were calculated, as well as the asymmetry and kurtosis with values close to 0 and <2.0. It is important to note that the data from this work were collected in schools so that the students could be nested based on the center, course and/or class, that is, violating the independence of observations principle. Therefore, the Mixed Linear Models analysis (MLM) were conducted, bearing in mind the individual characteristic variables of the participants and context variables. The dependent variables were the different ETCS-PE, ISC and CCDEF subscales, and the grouping or level of the school was considered a random effect, as were the student courses. The analyses were performed using the SPSS 23.0 MIXED procedure with the Restricted Maximum Likelihood Estimation Method. The Logarithm of Likelihood -2 (-2LL) ( Pardo et al., 2007 ) was used to estimate the effects of the school and course variable on each estimated model. Different models were tested according to the different combinations of school levels and course with each of the dependent variables, including a null model. The “school” variable proved statistically significant ( p < 0.05) in all cases, so it was estimated that the context variable “school” had an effect on each model. In addition, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for each of the compared variables. The results showed that the variance explained was greater than 6.14% in all cases, which allows us to say that a percentage of the differences between the dependent variables can be attributed to the school. The estimation method used was the restricted maximum likelihood estimation method. In light of the above, gender differences in relation to the various ETCS-PE, ISC and CCDEF subscales were calculated, in this case, the independent variable (mixed model factors) was the gender of the students. To calculate the differences according to teaching competence, the responses of this scale were categorized into three groups, low (responses 1 and 2 on the Likert scale), medium (responses 3, 4, and 5) and high (responses 6 and 7). The calculation of the differences between the three categorized groups of teaching competence in relation to satisfaction and boredom with school and disruptive behaviors was also conducted and, in this case, the independent variable (mixed model factors) was the teaching competence categorization.

Additionally, the factorial structure of each instrument was evaluated with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the Maximum Likelihood method with the bootstrapping procedure, since the Mardia coefficient was high in each of the scales (16.71 in ETCS-PE; 12.51 in ISC and 292.55 in CCDEF). The different analyses were performed using the SPSS v.23 and AMOS v.22 statistical packages.

Psychometric Properties of the Instruments

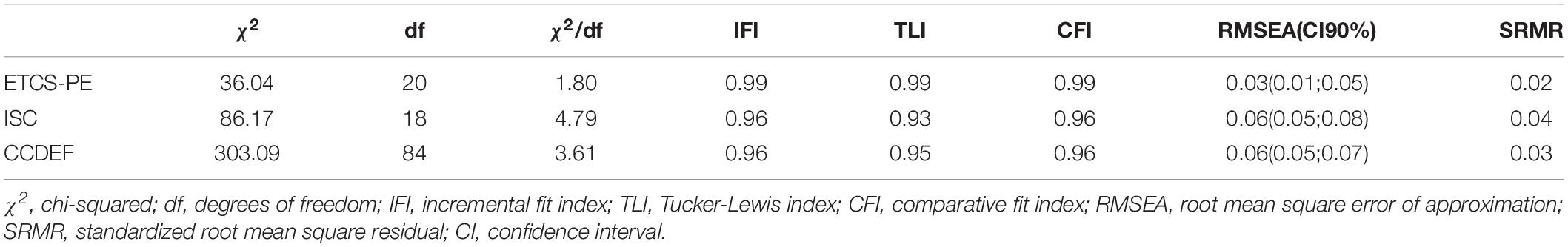

Based on recommendations that discourage the use of a single overall model-fit measure ( Bentler, 2007 ), each model was assessed using a combination of absolute and relative fit indices. The chi-squared ratio (χ 2 ) and the degrees of freedom (df) (χ 2 /df), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) the incremental fit index (IFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its confidence interval (CI 90%) and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) were calculated. In the (χ 2 /df) ratio, values < 2.0 are considered very good model fit indicators ( Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007 ), although values < 5.0 are considered acceptable ( Hu and Bentler, 1999 ). According to Hu and Bentler (1999) , for the incremental indices (CFI, IFI, and TLI), values ≥ 0.95 are considered to indicate a good fit, although values of ≥ 0.90 are considered acceptable. These same authors consider that, for RMSEA, a value of ≤ 0.06 is considered to indicate a good fit, while for the RMSR values ≤ 0.08 are considered acceptable. As can be observed in Table 2 , the different values for the goodness-of-fit indices of each instrument (ETCS-PE, ISC, and CCDEF) are acceptable.

Table 2. The goodness of fit index of the models.

Descriptive and Correlation Analysis

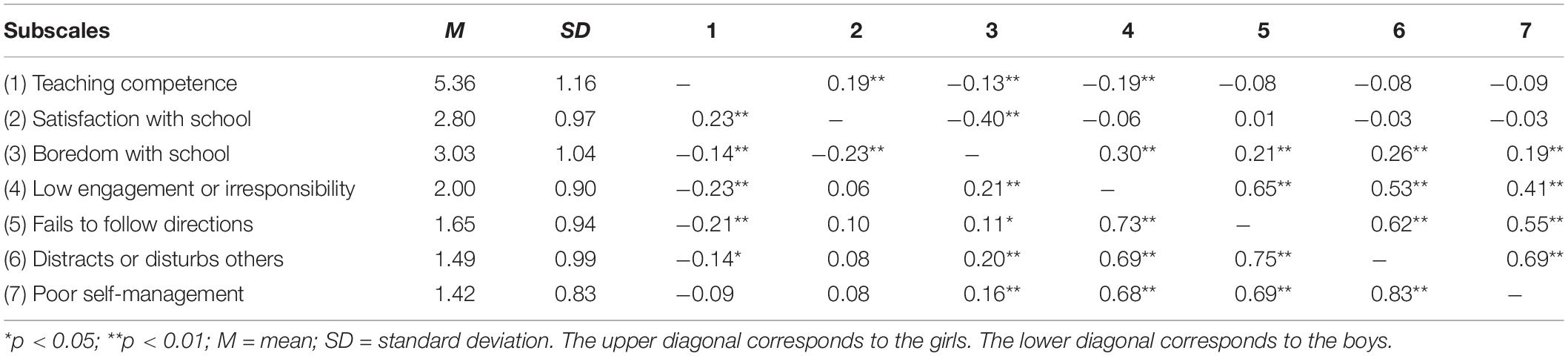

Table 3 shows that teaching competence presented moderately high average values, that for the ISC, the average values were higher for bored than for satisfaction with school , and that for disruptive behaviors, the average values were moderately low, oscillating between low engagement or irresponsibility and poor self-management , which presented the lowest average.

Table 3. Descriptives and correlations of the ECTS-PE, ISC, and CCDEF subscales.

The correlations show that teaching competence only presented positive, moderate, and statistically significant values for satisfaction with school . Disruptive behaviors presented high, positive and statistically significant correlations between the same CCDEF subscales although positive correlations with more moderate values were also found between the different disruptive and boredom with school subscales (see Table 3 ).

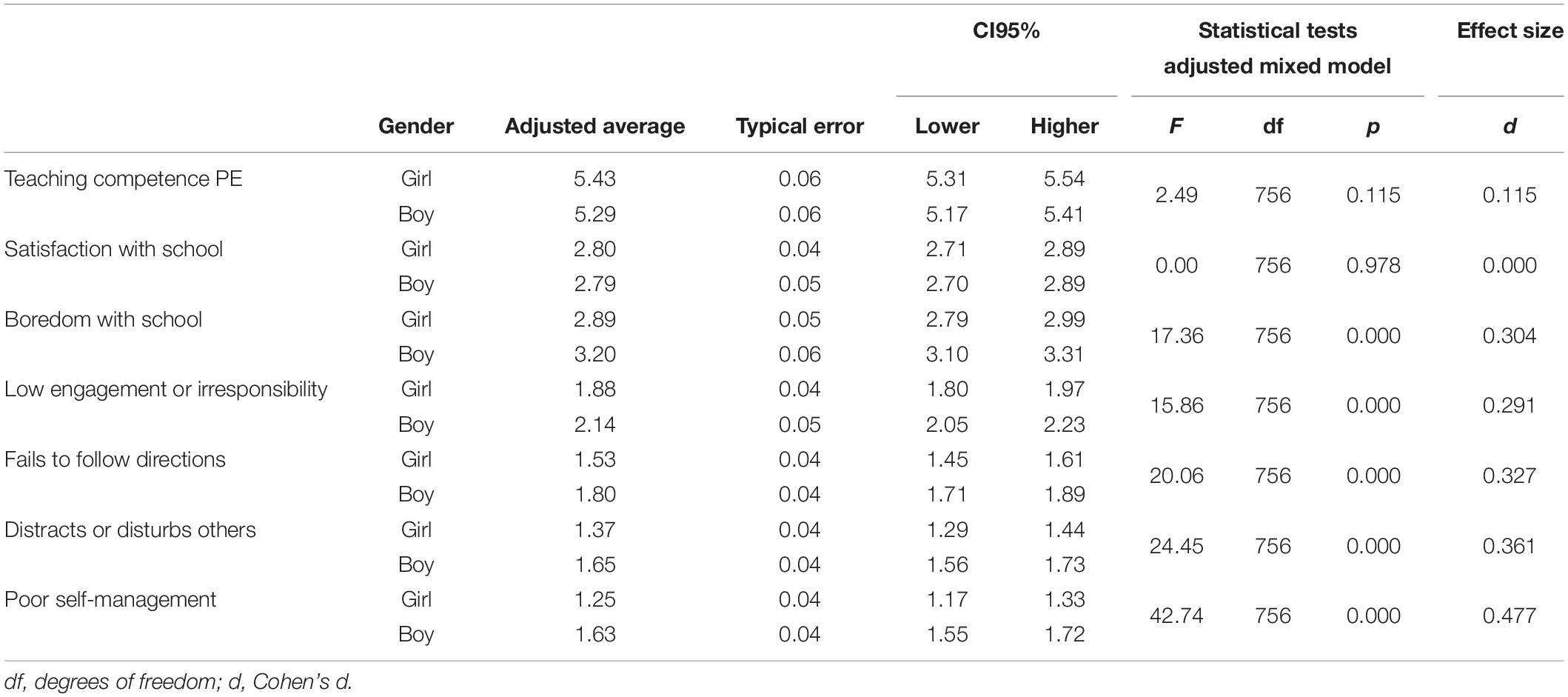

Differences According to the Gender Variable

The differences were analyzed between the various subscales of teacher competence, school satisfaction and disruptive behaviors according to the gender variable. As shown in Table 4 , the analyses indicate that there are statistically significant differences in the boredom with school and the four CCDEF subscales, and that, in all of them, the average values are higher for boys.

Table 4. Gender differences based on the ETCS-PE, ISC, and CCDEF subscales according to the mixed regression model.

Differences According to Teaching Competence

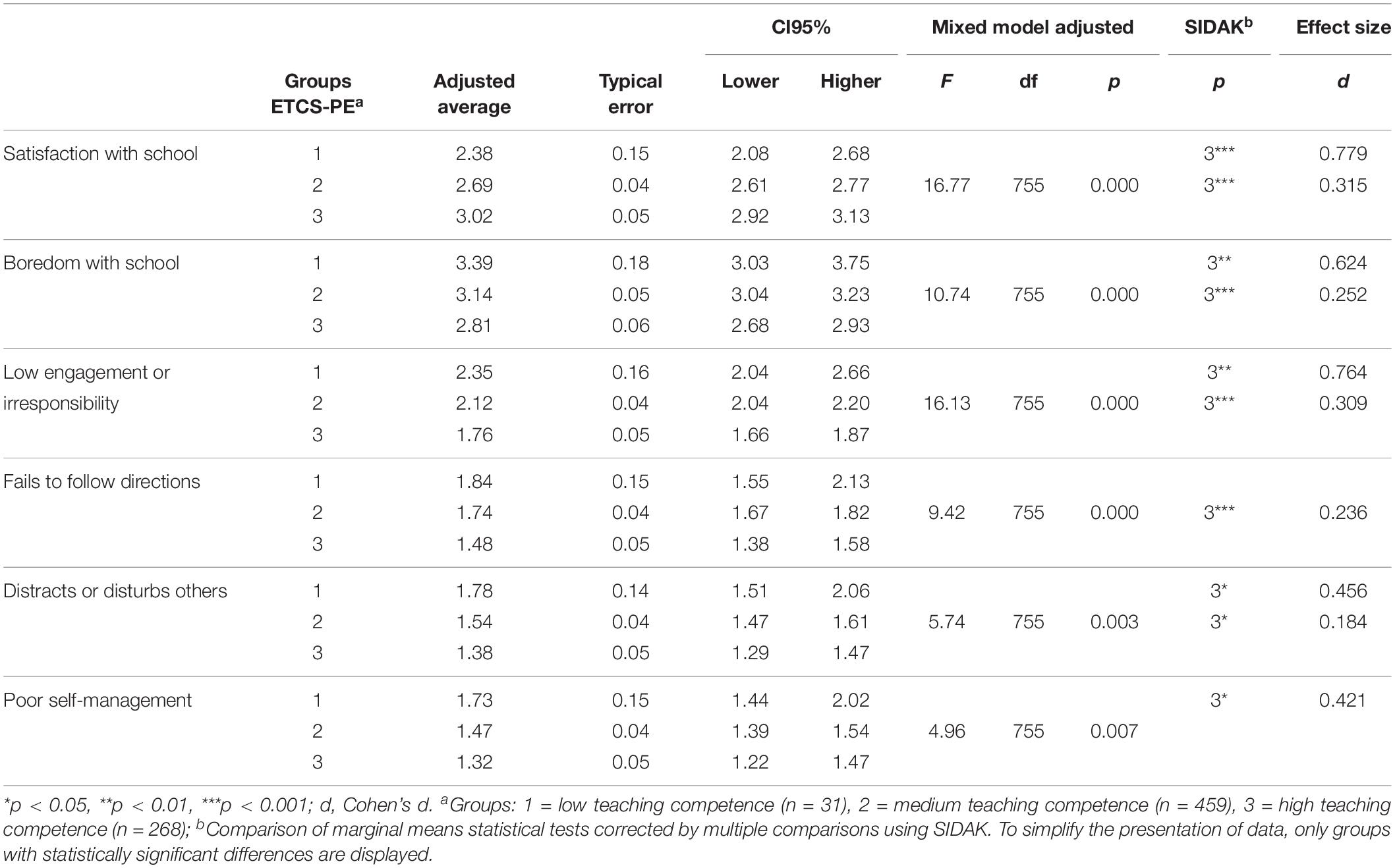

In order to check the differences in the satisfaction with school and the disruptive behaviors subscales, according to the three teaching competence groups (low, medium, and high), the analysis performed indicates that the p -value associated with the comparative statistical tests of marginal averages has been calculated and corrected for multiple comparisons using SIDAK ( Table 5 ).

Table 5. Differences in teaching competence (ETCS-PE) based on the ISC and CCDEF subscales according to the mixed regression model.

Table 5 shows that there are statistically significant differences in all the subscales studied. In the case of satisfaction with school, the highest averages correspond to the high teaching competence group, whereas for boredom with school and the four CCDEF subscales, the highest average values are presented by the low teaching competence group.

Regarding satisfaction with school and boredom with school, comparison tests show statistically significant differences between low and high teaching competence and between those of medium and high teaching competence, corrected using SIDAK (see Table 5 ). In the cases of disruptive behaviors, for low engagement or irresponsibility and fails to follow directions, statistically significant differences are notable between medium and high teaching competence; in the case of the Distracts or disturbs others subscale, statistically significant differences were found between high teaching competence and the other two groups, while in poor self-management, they were only found between low and high teaching competence.

This study set out two objectives: to understand the differences that exist in school satisfaction, disruptive behaviors and teaching competencies according to the gender of the students; and to analyze school satisfaction and disruptive behaviors based on teaching competence.

The results of this work relate teaching competence, satisfaction with school and inappropriate behaviors in the classroom. As in other studies (e.g., Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ), the children presented higher levels of disruptive behavior. These results might be due to the boredom experienced by adolescents coming from a lack of attachment to social institutions and from disruptive behaviors at school ( Feinberg et al., 2013 ; Granero-Gallegos et al., 2020 ). It is essential that students do not experience boredom in school, given that it is related to school violence, and this in turn can contribute to reduced academic performance, mental health and general well-being of the students ( Huebner et al., 2014 ; Olweus and Breivik, 2014 ). In addition, boredom has been associated with high-risk behaviors such as drinking, drug use, joyriding and criminal activity ( Yang and Yoh, 2005 ; Wegner and Flisher, 2009 ). Therefore, it is important that teachers work on their social skills with students and acquire sufficient competency as educators so that, amongst other things, both feel satisfied in classes ( Allen et al., 2015 ; Trigueros and Navarro, 2019 ). Accordingly, this confirms Hypothesis 1.

If one looks at the mixed regression model, no significant differences were found in the teacher competence and school satisfaction variables based on gender. However, significant differences were found in the boredom with school, low engagement or irresponsibility, fails to follow directions, distracts or disturbs others and poor self-management variables, with boys presenting higher values than girls. These results are similar to those obtained in previous studies (e.g., Beaman et al., 2006 ; Kulinna et al., 2006 ; Cothran and Kulinna, 2007 ; Driessen, 2011 ), in which higher levels of disruptive behavior were also found in boys. They may be due to boys being more defiant with the teacher and more competitive with their peers, seeking to get the attention of the girls. In addition, it has been observed that males tend to engage in louder and more intentional behaviors to distract their peers in class ( Glock and Kleen, 2017 ). Also, a possible cause for the increased level of negative behaviors has been linked to low emotional support from the teacher ( Shin and Ryan, 2017 ). All this can be the basis for proposing more comprehensive teacher training, not only at the technical level, but also in the management of emotions, both in the initial training and in the continuous workplace training. In contrast, the girls presented more positive and less problematic behaviors, as was the case in other studies (e.g., Driessen, 2011 ). This may be because girls tend to demonstrate more introverted behavior, being uninvolved, shy and avoiding working as a group to give their opinion on a topic ( Glock and Kleen, 2017 ). Therefore, this does not confirm Hypothesis 2 in its entirety.

The model analyzed based on teacher competencies found that when students perceived PE teachers as being competent, they felt more satisfied with the school, less bored and that their disruptive behavior level fell. Conversely, when students perceived their teachers as being incompetent, they became more bored and inappropriate behaviors increased. Similar results were found in the study by Baños et al. (2019) , which was conducted in the same country as our work. These results suggest that the way teachers interact with their students affects classroom behavior ( Ryan et al., 2015 ). This highlights the importance of PE teachers acquiring a great deal of skills to control and manage the sessions, creating a proactive environment among students, thus decreasing the likelihood of bad behaviors ( Shin and Ryan, 2014 ; Fortuin et al., 2015 ). However, teachers reporting high levels of concern regarding how to effectively manage discipline issues in the classroom are common ( Evertson and Weinstein, 2006 ; Tsouloupas et al., 2010 ) as they feel incompetent in the face of certain situations and this can be related to academic failure ( Jurado-de-los-Santos and Tejada-Fernández, 2019 ). The inability to prevent and control student misbehavior is one of the main generators of teacher stress and anxiety, resulting in teachers burning out and increasing the likelihood of student truancy – with all the expenses that this involves for the educational system in terms of having to find substitute teachers ( Tsouloupas et al., 2010 ; Ervasti et al., 2011 ). Therefore, this confirms Hypothesis 3.

PE teachers affirm that they find it more difficult to manage the boys’ behavior ( Jackson and Smith, 2000 ). These higher management issues may be due to the fact that teachers assess the temperament and educational competence of boys more negatively than those of girls ( Mullola et al., 2012 ) and that boys more frequently show emotional opposition behaviors than girls do ( McClowry et al., 2013 ). These differential behaviors in students and the teachers’ perceptions are reflected in less intimate and more conflictive relationships between teachers and boys ( Spilt et al., 2012 ). As a result, male students receive more reprimands ( Beaman et al., 2006 ) than female students, making it harder to manage the boys’ behavior ( McClowry et al., 2013 ). This implies less effective classroom management with respect to males, as research has emphasized the importance of positive relationships between the teachers and the students to promote good classroom management ( Marzano and Marzano, 2003 ). Therefore, teacher training is needed to better support trust and good management in the classroom.

The results obtained from this study identify males as having higher levels of inappropriate behaviors and the importance of students perceiving their teachers as being competent, that teachers have a command of the pedagogical content ( Voss et al., 2011 ) and knowledge of classroom management techniques ( Emmer and Stough, 2001 ) so that they can help reduce misbehavior in PE. Therefore, it is essential that adolescents perceive the PE teacher as competent, providing emotional support to his/her students, and that he/she continues to train in areas such as conflict resolution in the classroom, didactics and teacher pedagogy.

From this study, some recommendations can be made to bring, both to the classroom and to school. In general, the creation or strengthening of classrooms for school coexistence that improves the reflection, help, and accompaniment by other selected students can be recommended; it would be a program based on responsibility and without punishments or sanctions, and contribute to the resolution of conflicts in a positive way. By law, all educational centers must have a School Coexistence Plan, which must be implemented. More particularly, it is possible to focus on approaches that imply an enhancement of the motivation among students, especially in boys. Also, the enhancement of teaching competence in several topics (e.g., communication, work awareness, individual consideration of the student, problem-solving, social awareness, etc.), although the educational administration should supply teachers continuous training to improve social skills and capacity to solve conflicts among students.

Limitations and Strengths

The notable strengths of this work are the sample size and the theme, which can contribute to remedying one of the main problems found on a day-by-day basis in secondary schools. However, despite the novelty and interest of the topic and the results provided in this study such as the relationship between teaching competence and disruptive behaviors, as well as the implications this might have at the pedagogical and teacher-training level, certain limitations should be taken into account. The sample is composed of secondary school students from a single autonomous region and, in addition, no probabilistic sample design was carried out, so the results cannot be generalized and the method used does not allow to deeper into the disruptive causes in the classroom. Further studies should be performed in which other research designs are proposed, such as experimental studies with intervention programs to reduce disruptive behaviors in the classroom, and which consider other variables related to teacher, or mixed quantitative and qualitative research designs could be proposed, focusing on all subjects, not just PE. Some of these studies could also include private schools and public schools located in different socioeconomic level areas. On the other hand, it would also be convenient to perform longitudinal researches, with various data collections, in which the effectiveness of coexistence programs is valued.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by REF-45-20/01/2016. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

AG-G, RB, and AB-E conceived the hypothesis of this study. RB, AB-E, and MM-M participated in data collection. RB and AG-G analyzed the data. AG-G, AB-E, and MM-M wrote the manuscript with the most significant input from AB-E. All authors contributed to data interpretation of statistical analysis and read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Agbuga, B., Xiang, P., and McBride, R. (2010). Achievement goals and their relations to children’s disruptive behaviors in an after-school physical activity program. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 29, 278–294. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.29.3.278

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Ahmed, W., Van der Werf, G., Kuyper, H., and Minnaert, A. (2013). Emotions, self-regulated learning, and achievement in mathematics: a growth curve analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 150–161. doi: 10.1037/a0030160

Allen, J. P., Hafen, C. A., Gregory, A., Mikami, A., and Pianta, R. C. (2015). Enhancing secondary school instruction and student achievement: replication and extension of the My Teaching Partner—Secondary Intervention. J. Res. Educ. Eff. 8, 475–489. doi: 10.1080/19345747.2015.1017680

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baena-Extremera, A., and Granero-Gallegos, A. (2015). Prediction model of satisfaction with physical education and school. Rev. Psicodidact. 20, 177–192. doi: 10.1387/RevPsicodidact.11268

Baena-Extremera, A., Granero-Gallegos, A., and Martínez-Molina, M. (2015). Validación española de la Escala de Evaluación de la Competencia Docente en Educación Física de secundaria [Spanish version of the Evaluation of Teaching Competencies Scale in secondary school Physical Education]. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte 15, 113–122.

Google Scholar

Baños, R., Ortiz-Camacho, M. M., Baena-Extremera, A., and Tristán-Rodríguez, J. L. (2017). Satisfacción, motivación y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de Secundaria y Bachillerato [Satisfaction, motivation and academic performance in secondary and high school students: background, design, methodology and proposal of analysis for a research paper]. Espiral 10, 40–50.

Baños, R., Ortiz-Camacho, M. M., Baena-Extremera, A., and Zamarripa, J. (2018). Efecto del género del docente en la importancia de la Educación Física, clima motivacional, comportamientos disruptivos, la intención de práctica futura y rendimiento académico [Effect of teachers’ gender on the importance of physical education, motivational climate, disruptive behaviours, future practice intentions, and academic performance]. Retos 33, 252–257.

Baños, R. F., Baena-Extremera, A., Ortiz-Camacho, M. M., Zamarripa, J., Beltrán, A., and Juvera-Portilla, J. L. (2019). Influencia de las competencias del profesorado de secundaria en los comportamientos disruptivos en el aula [Influence of the competencies of secondary teachers on disruptive behavior in the classroom]. Espiral 12, 3–10. doi: 10.25115/ecp.v12i24.21

Beaman, R., Wheldall, K., and Kemp, C. (2006). Differential teacher attention to boys and girls in the classroom. Educ. Rev. 58, 339–366. doi: 10.1080/00131910600748406

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 42, 825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Castillo, I., Balaguer, I., and Duda, J. L. (2001). Las perspectivas de meta de los adolescentes en el contexto deportivo. Psicothema 14, 280–287.

Catano, V. M., and Harvey, S. (2011). Student perception of teaching effectiveness: development and validation of the Evaluation of Teaching Competencies Scale (ETCS). Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 36, 701–717. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2010.484879

Cothran, D. J., and Kulinna, P. H. (2007). Students’ reports of misbehavior in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 78, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2007.10599419

Cothran, D. J., Kulinna, P. H., and Garrahy, D. (2009). Attributions for and consequences of student misbehavior. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 14, 155–167. doi: 10.1080/17408980701712148

Diener, E. (2009). “Assessing well-being: progress and opportunities,” in Assessing Well-Being. The Collected works of Ed Diener , ed. E. Diener, (New York: Springer), 25–65. Social Indicators Research Series, 39. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_3

Diener, E., and Emmons, R. A. (1985). The independence of positive and negative affect. J. Pers. Assess. 99, 91–95.

Driessen, G. (2011). Gender differences in education: is there really a “boys’ problem? Paper presented at the Annual Meeting ECER , Berlin

Duda, J. L., and Nicholls, J. G. (1992). Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 84, 290–299. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.290

Emmer, E. T., and Stough, L. M. (2001). Classroom management: a critical part of educational psychology, with implications for teacher education. Educ. Psychol. 36, 103–112. doi: 10.1207/S15326985EP3602_5

Ervasti, J., Kivima, M., Puusniekka, R., Luopa, P., Pentti, J., Suominen, S., et al. (2011). Students’ school satisfaction as predictor of teachers’ sickness absence: a prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Public Health 22, 215–219. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr043

Evertson, C. M., and Weinstein, C. S. (2006). Handbook of Classroom Management: Research Practice and Contemporary Issues. Mahwah NJ: Routledge.

Feinberg, M. E., Sakuma, K. L., Hostetler, M., and McHale, S. M. (2013). Enhancing sibling relationships to prevent adolescent problem behaviors: theory, design and feasibility of Siblings Are Special. Evlau. Program. Plann. 36, 97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.08.003

Fortuin, J., van Geel, M., and Vedder, P. (2015). Peer influences on internalizing and externalizing problems among adolescents: a longitudinal social network analysis. J. Youth Adolescence 44, 887–897. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0168-x

Fredericks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., and Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 74, 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059

Geven, S., Jonsson, J. O., and van Tubergen, F. (2017). Gender differences in resistance to schooling: the role of dynamic peer-influence and selection processes. J. Youth Adolescence 46, 2421–2445. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0696-2

Glock, S., and Kleen, H. (2017). Gender and student misbehavior: evidence from implicit and explicit measures. Teach. Teach. Educ. 67, 93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.015

Goyette, R., Dore, R., and Dion, E. (2000). Pupils’ misbehaviors and the reactions and causal attributions of physical education student teachers: a sequential analysis. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 20, 3–14. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.20.1.3

Granero-Gallegos, A., and Baena-Extremera, A. (2016). Validación española de la version corta del Physical Education Classroom Instrument para la medición de conductas disruptivas en alumnado de secundaria [Validation of the short-form Spanish version of the Physical Education Classroom Instrument measuring secondary pupils’ disruptive behaviours]. Cuadernos de Psicología del Deporte 16, 89–98.

Granero-Gallegos, A., Gómez-López, M., Baena-Extremera, A., and Martínez-Molina, M. (2020). Interaction effects of disruptive behaviour and motivation profiles with teacher competence and school satisfaction in secondary school physical education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17:114. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17010114

Granero-Gallegos, A., Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Baena-Extremera, A., and Martínez-Molina, M. (2019). Effects of motivation, basic psychological needs, and teaching competence on disruptive behaviours in secondary school physical education students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16:4828. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16234828

Hadjar, A., and Buchmann, C. (2016). “Education systems and gender inequalities in educational attainment,” in Education Systems and Inequalities: International Comparisons , eds S. L. Christenson, A. Hadjar, and C. Gross, (Bristol: Policy Press), 159–182.

Helsinki Declaration (2008). World Medical Association. Available at: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/doh-oct2008/

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., Jiang, X., Long, R. F., Kelly, R., and Lyons, M. D. (2014). “Schooling and Children’s Subjective Well-Being,” in Handbook of Child Well-Being SE - 26 , eds A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, and J. E. Korbin, (Netherlands: Springer), 797–819. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_26

Invernizzi, P. L., Crotti, M., Bosio, A., Cavaggioni, L., Alberti, G., and Scurati, R. (2019). Multi-teaching styles approach and active reflection: effectiveness in improving fitness level, motor competence, enjoyment, amount of physical activity, and effects on the perception of physical education lessons in primary school children. Sustainability 11, 405–425. doi: 10.3390/su11020405

Jackson, C., and Smith, I. D. (2000). Poles apart? An exploration of single-sex educational environments in Australia and England. Educ. Stud. 26, 409–422. doi: 10.1080/03055690020003610

Jurado-de-los-Santos, P., and Tejada-Fernández, J. (2019). Disrupción y fracaso escolar. Un estudio en el contexto de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria en Cataluña [Disruption and School Failure. A Study in the Context of Secondary Compulsory Education in Catalonia]. Estud Sobre Educ. 36, 135–155. doi: 10.15581/004.36.135-155

Krech, P. R., Kulinna, P. H., and Cothran, D. (2010). Development of a short-form version of the Physical Education Classroom Instrument: measuring secondary pupils’ disruptive behaviours. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagogy 15, 209–225. doi: 10.1080/17408980903150121

Kulinna, P. H., Cothran, D., and Regualos, R. (2006). Teachers’ reports of student misbehavior in physical education. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 77, 32–40. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2006.10599329

Marzano, R. J., and Marzano, J. S. (2003). The key to classroom management. Educ. Leadersh. 61, 6–18.

McClowry, S. G., Rodriguez, E. T., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Spellmann, M. E., Carlson, A., and Snow, D. L. (2013). Teacher/student interactions and classroom behavior: the role of student temperament and gender. J. Res. Child Educ. 27, 283–301. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2013.796330

Medina, J. A., and Reverte, M. J. (2019). Incidencia de la práctica de actividad física y deportiva como reguladora de la violencia escolar. Retos 35, 54–60.

Müller, C. M., Hofmann, V., Begert, T., and Cillessen, A. H. (2018). Peer influence on disruptive classroom behavior depends on teachers’ instructional practice. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 56, 99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.04.001

Mullola, S., Ravaja, N., Lipsanen, J., Alatupa, S., Hintsanen, M., Jokela, M., et al. (2012). Gender differences in teachers’ perceptions of students’ temperament, educational competence, and teachability. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 82, 185–206. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02017.x

Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The Competitive Ethos and Democratic Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Nicholls, J. G., Patashnick, M., and Nolen, S. B. (1985). Adolescents’ theories of education. J. Educ. Psychol. 77, 683–692. doi: 10.1037//0022-0663.77.6.683

Olweus, D., and Breivik, K. (2014). “Plight of victims of school bullying: the opposite of well-being,” in Handbook of Child Well-Being SE - 90, eds A. Ben-Arieh, F. Casas, I. Frønes, and J. E. Korbin, (Netherlands: Springer), 2593–2616. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9063-8_26

Pardo, A., Ruiz, M., and San Martín, R. (2007). Cómo ajustar e interpretar modelos multinivel con SPSS [How to fit and interpret multilevel models using SPSS]. Psicothema 19, 308–321.

Persson, L., Haraldsson, K., and Hagquist, C. (2016). School satisfaction and social relations: swedish school children’s improvement suggestions. Int. J. Public Health 61, 83–90. doi: 10.1007/s00038-015-0696-5

Rasmussen, J. F., Scrabis-Fletcher, K., and Silverman, S. (2014). Relationships among tasks, time, and student practice in elementary physical education. Phys. Educ. 71, 114–131.

Ryan, A. M., Kuusinen, C., and Bedoya-Skoog, A. (2015). Managing peer relations: a dimension of teacher self-efficacy that varies between elementary and middle school teachers and is associated with observed classroom quality. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 41, 147–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.01.002

Scharenberg, K. (2016). The interplay of social and ethnic classroom composition, tracking, and gender on students’ school satisfaction. J. Cogn. Educ. Psychol. 15, 320–346. doi: 10.1891/1945-8959.15.2.320

Shin, H., and Ryan, A. M. (2014). Friendship networks and achievement goals: an examination of selection and influence processes and variations by gender. J. Youth Adolescence 43, 1453–1464. doi: 10.1007/s10964-014-0132-9

Shin, H., and Ryan, A. M. (2017). Friend influence on early adolescent disruptive behavior in the classroom: teacher emotional support matters. Dev. Psychol. 53, 114–126. doi: 10.1037/dev0000250

Spilt, J. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., and Jak, S. (2012). Are boys better off with male and girls with female teachers? A multilevel investigation of measurement invariance and gender match in teacher-student relationship quality. J. Sch. Psychol. 50, 363–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.12.002

Sun, R. C. (2016). Student misbehavior in Hong Kong: the predictive role of positive youth development and school satisfaction. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 11, 773–789. doi: 10.1007/s11482-015-9395-x

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, S. A. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics , 5th Edn. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Takakura, M., Wake, N., and Kobayashi, M. (2010). The contextual effect of school satisfaction on health-risk behaviors in Japanese high school students. J. Sch. Health 80, 544–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00540.x

Trigueros, R., and Navarro, N. (2019). La influencia del docente sobre la motivación, las estrategias de aprendizaje, pensamiento crítico de los estudiantes y rendimiento académico en el área de educación física. Psychol. Soc. Educ. 11, 137–150. doi: 10.25115/psye.v11i1.2230

Tsouloupas, C. N., Carson, R. L., Matthews, R., Grawitch, M. J., and Barber, L. K. (2010). Exploring the association between teachers’ perceived student misbehaviour and emotional exhaustion: the importance of teacher efficacy beliefs and emotion regulation. Educ. Psychol. 30, 173–189. doi: 10.1080/01443410903494460

Varela, J. J., Zimmerman, M. A., Ryan, A. M., Stoddard, S. A., Heinze, J. E., and Alfaro, J. (2018). Life satisfaction, school satisfaction, and school violence: a mediation analysis for Chilean adolescent victims and perpetrators. Child Indic. Res. 11, 487–505. doi: 10.1007/s12187-016-9442-7

Voss, T., Kunter, M., and Baumert, J. (2011). Assessing teacher candidates’ general pedagogical/psychological knowledge: test construction and validation. J. Educ. Psychol. 103, 952–969. doi: 10.1037/a0025125

Wegner, L., and Flisher, A. J. (2009). Leisure boredom and adolescent risk behaviour: a systematic literature review. J. Child Adol. Ment. Health 21, 1–28. doi: 10.2989/JCAMH.2009.21.1.4.806

Weiss, M. R., Smith, A. L., and Stuntz, C. P. (2008). “Moral development in sport and physical activity,” in Advances in Sport Psychology , ed. T. S. Horn, (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics), 187–210.

Yang, H., and Yoh, T. (2005). The relationship between free-time boredom and aggressive behavioral tendencies among college students with disabilities. Am. J. Recreat. Ther. 4, 11–16.

Keywords : physical education, disruptive behavior, indiscipline, high school, satisfaction

Citation: Granero-Gallegos A, Baños R, Baena-Extremera A and Martínez-Molina M (2020) Analysis of Misbehaviors and Satisfaction With School in Secondary Education According to Student Gender and Teaching Competence. Front. Psychol. 11:63. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00063

Received: 12 November 2019; Accepted: 10 January 2020; Published: 28 January 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Granero-Gallegos, Baños, Baena-Extremera and Martínez-Molina. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Raúl Baños, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Interventions to Address Students' Misbehavior in Puro National High School

- Jonie Oliver

INTRODUCTION

Students misbehavior as defined by Reed & Kirkpatrick (1998) as disruptive talking, chronic avoidance of work, clowning, interfering with teaching activities, harassing classmates, verbal insults, rudeness to teacher, defiance, and hostility. Furthermore, misbehavior was also related to high school grades, test scores, and graduation and dropout rates (Finn, Fish & Scott,2010). Drop out is one of the school's problems that cannot be avoided. Thus, it triggered them to identify the misbehavior of students inside the classroom and the intervention to address the problem.

This descriptive-qualitative action research aimed to produce interventions to address the problem of misbehavior among Grade 7 to 10 students of Puro National High School. The respondents to this study were students, teachers, and school head, parents, and other community members. Survey questionnaires and interview guide were the research instrument used in gathering the data.

The study found that fighting, bullying, cutting class, disrespect to teachers, and disturbing other classmates and verbal abuse are the most common student misbehavior. Peer pressure (influence from "barkada"), exposure to violence (parents quarrel/argue often and habitual involvement in fighting), poor role models (parent/guardian with vices), and poor diet/nutrition (did not eat breakfast), respectively, are considered topmost in rank as causes of bad behavior. To address these concerns, the usual interventions made by teachers and school administrator are behavior conference, informing the parents, and reminder, and guidance counseling among others, respectively. Parents also intervene through reprimand and one-on-one talk.

DISCUSSIONS

Reconsidering these interventions, the study concludes that immediate interventions are necessary, such as supervising of "barkada" relations, counseling of parents who often quarrel and parents with vices and encouraging students to eat breakfast. More importantly, this research stated that a procedural and reasonable intervention involves the revision of school rules and regulations, crafting of a step-by-step intervention process, and creation of a committee on guidance and counseling with a document on the roles and responsibilities of the members. Lastly, recommendations were given such as information dissemination regarding school rules and regulations, strict observance to the intervention process, and continuous annual research by the committee on guidance and counseling members.

Information

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

©2017 by Ascendens Asia Pte. Ltd. | NLB Singapore-Registered Publisher.

- Español

Introduction

Classroom management is one of the most important dimensions of the teaching and learning process. It is believed that good classroom management helps establish an effective and conducive learning environment (Kubat & Dedebali, 2018); improve students’ learning outcome (Slater & Main, 2020); effectively deal with children who have behavioral issues (Zulkifli et al., 2019), and help reduce students’ disruptive behaviors in the classroom (Affandi et al., 2020). For these reasons, classroom management has become the frequent subject of research in the educational field (George et al., 2017), including in the EFL contexts (e.g., Habibi et al., 2018; Soleimani & Razmjoo, 2016). Consequently, although there are several evidence-based strategies highlighted by previous studies on classroom management, a little is discussed on disruptive behaviors of students and how it is being managed by secondary teachers in the EFL context, Bhutan. This study was conducted considering teachers should be aware of practices to overcome disruptive behaviors in the classroom in order to effectively conduct the classes and for the success of students’ learning (Simonsen et al., 2008).

Disruptive behavior is roughly defined as inappropriate behavior of students in the classroom that impedes both learning and teacher’s instructions (Gómez Mármol et al., 2018; Närhi et al., 2017). Some of the most common disruptive behaviors include learners’ inappropriate gestures, talking with classmates, physical and verbal aggressiveness, moving in the class, shouting, and not respecting the classroom rules (Esturgó-Deu & Sala-Roca, 2010). Fact that disruptive behavior in the classroom is an undeniable problem faced by teachers of all generations (Abeygunawardena & Vithanapathirana, 2019), many research studies have been carried out investigating the causes of this disruptive behavior and developing possible intervention strategies (Rafi et al., 2020).

Although there is a vast literature on students’ disruptive behavior in the field of education, little has been done in EFL classrooms, particularly in the Asian context. As each region, country, local setting/context and school have a different learning environment, culture, and tradition, there was a need to conduct a study in Bhutan regarding the issue of disruptive behavior. As evidence-based intervention strategies were not regularly followed by institutions/schools to reduce disruptive behavior (Dufrene et al., 2014), this study was conducted to specifically investigate how seating arrangements can help reduce students’ disruptive behavior in the language classroom.

Literature Review

Disruptive behavior

Disruptive behavior in the classroom is one of the most widely expressed concerns among teachers and school administrators (Duesund & Ødegård, 2018; Nash et al., 2016). The belief is that the presence of disruptive behavior or discipline issues in the classroom negatively affects students learning (Gómez Mármol et al., 2018) and lowers students’ academic performance (Granero-Gallegos et al., 2020). Not only students are affected. Cameron and Lovett (2015) asserted that disruptive behavior in the classroom was one of the factors which adversely shaped teachers’ attitudes about teaching, and also highlighted those teachers show less interest in teaching when students exhibit disruptive behavior in the classroom. Moreover, students’ disruptive behavior is considered to have a direct link with the mental, physical and emotional well-being of teachers and may deteriorate teachers’ ability to educate the students to some extent (Shakespeare et al., 2018).

Cause of disruptive behavior

There seem to be several reasons why students exhibit disruptive behavior in the classroom. Many are associated with the community, parents, teachers, and students themselves. Factors such as a bad influence from the community, a lack of preparation and low teaching quality, poor parenting, students’ attitude towards learning, and students’ emotional and mental problems (Khasinah, 2017) can cause unsuitable behavior in the classroom. Likewise, Latif et al. (2016) also noted others including large classes, teachers’ biased attitudes toward students, and students’ desires to get attention in the classroom as other reasons students exhibit disruptive behavior in the classroom.

As for the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom, the cause of discipline problems have been reported to be a low level of student engagement when students cannot understand the lesson taught in the classroom and experience minimal progress of target language; learning difficulties caused by their difficulty in understanding vocabulary, and grammar in the English language; attention-seeking when students want to attract teachers’ and peers’ attention; fatiguewhen students are sleepy and bored, and the influence of technology when students use mobile phones and other electronic gadgets in the middle of class activity (Jati et al., 2019).

Preventing disruptive behavior

Admittedly, much of the previous research in the field does not discuss how intervention strategies assist in reducing or overcoming the disruptive behavior of students, particularly in the language classroom. This is not surprising since the teachers’ abilities differ in terms of classroom management skills (Khasinah, 2017). Intervention strategies most often proposed in the literature to combat discipline issues in the classroom are, for example: praising, motivating, or reinforcing students; maintaining a positive/close relationship with students; formulating basic classroom rules at the beginning of the courses; adapting student-centered learning, and frequently changing the seating arrangements (Rafi et al., 2020).

Intervention strategies used in this study

Much is written on the benefits of the seating arrangement on the classroom learning environment including students’ academic performance, students’ cognitive ability, participation in class, and general behavior. For instance, Tobia et al. (2020) asserted that children become more logical, creative, and exhibit better classroom behavior when they were seated individually on a single desk. Likewise, Pichierri and Guido (2016) noted that classroom seating arrangement is a crucial factor that can have a significant influence on students’ academic performance. These authors supported this statement with their findings which showed that the students sitting in front of the class significantly outperformed the students who were seating on the back rows. Additionally, Egounléti et al. (2018) pointed out that the seating arrangement facilitates students’ participation, especially when they are seated in pairs or groups. In general, previous research seems to suggest that seating arrangements can have a positive effect on teaching and learning in language classrooms.

- Therefore, the study had the following objectives:

- To investigate the most common disruptive behaviors among seventh grade EFL students in the English language classroom.

- To examine whether an intervention strategy such as seating arrangements as used in this study could help reduce students’ disruptive behavior in the classroom.

- To explore students' perceptions about classroom disruptive behavior.

Methodology

This study was conducted in one of the countries which has been the least studied, Bhutan (Wangdi & Tharchen, 2021). For this reason, readers need to understand the context of the study to allow them to understand the importance of carrying out this action research (AR). Bhutan is a small land-locked country located in South Asia with a population of approximately 775,000 people. To date, more than half (57.4%) of the Bhutanese population live in rural areas. The first modern school in Bhutan was established in 1914 by then the first king of Bhutan, Gongsa Ugyen Wangchuk. Ever since then education has been the primary focus in Bhutan. The present overall literacy rate for over 6 years is 66 % (73% male and 59% female). Although this is a great achievement for a developing country like Bhutan, as with any other country, Bhutan's education system faces a lot of challenges. One of the prominent challenges that Bhutanese students face is mastering the English language. The English proficiency level of the Bhutanese students is still below the expected competency even to date (Choeda et al., 2020). As Wangdi and Tharchen (2021) stated that having research done by the teachers themselves helps promote their pedagogical knowledge, teaching practices, and students learning outcome at large, thus this study was conducted with the hope to help students learn English properly in the classroom without any disruptions.

Participants

It should be noted that this study was classroom-based AR. Therefore, this research employed a convenient sampling technique to recruit the participants. A total of 32 secondary students from Dechentsemo Central (public) School in Bhutan participated in this study. These students were studying with the researcher, who was also a classroom teacher. Out of the 32, twenty were boys and twelve were girls aged between twelve and fourteen. The majority of participants were thirteen years old (nineteen students), followed by fourteen years old (eight students), and twelve years old (five students). They were in grade seven and they took a basic English as communication course.

Ethical considerations

First, researchers asked written permission from the head of Dechentsemo Central (public) School in Bhutan. After getting a letter of consent from the head of the school, the consent letter from classroom teachers and students’ parents was acquired through emails. For this, an email consisting of a brief explanation of research objectives was sent to classroom teachers and students’ parents. They were informed that the data collection would be done solely for research purposes and it would neither hinder or affect the teaching schedule nor students’ grades in any way. Following this, verbal consent from students was also obtained. After having permission from the school head, classroom teachers, student parents, and students themselves the researchers started collecting the data.

Research design

This article summarises AR conducted by a classroom teacher, who was also a researcher as part of continuing professional development. AR is critical classroom-based inquiry conducted by teachers or academicians themselves to identify a specific classroom problem and concurrently to improve them (Zambo, 2007). Conducting AR by teachers themselves not only helps them grow professionally, but also improves their teaching practices (Makoelle & Thwala, 2019). AR may also enhance the level of teachers’ effectiveness and quality of education at large. In this sense, following Dickens and Watkins (1999) and a modified Lewin’s (1946) model that includes four cycles in conducting AR, (planning, acting, observing, and reflection), this study investigated to what extent the frequent change of seating arrangements in the classroom helps reduce students’ disruptive behaviors. The AR model used in this research is presented below.

Figure 1: Dickens and Watkins’s (1999) AR model

To carry out this study, researchers followed the following steps.

The researchers reviewed the current issues and practices available in the literature that discussed disruptive behaviors in the language classroom and how it negatively impacted teachers’ instruction and students’ learning. Having identified the aspect that we wanted to explore or use as an intervention strategy, we decided to explore the effectiveness of a frequent change of seating arrangements in reducing disruptive behavior.

Step 1. Researchers observed two EFL classes for almost a month, eight classes to be precise (twice per week) to examine the most common disruptive behavior among the students in the classroom. In other words, the observation was done before the treatment (pre-intervention, hereafter). The data were recorded using two different instrumentations. First, for two classes, the researcher observed different types of disruptive behavior that the students exhibited and took note of it. Second, a daily checklist was used to identify the most frequent/repeating types of disruptive behavior among these students to compare with the post-intervention data.

Step 2. Researchers examined how the seating arrangements used as an intervention strategy in this study assisted in reducing disruptive behavior that students exhibited in the English language classroom. The students were observed two times per week (Monday & Wednesday) for three months. The treatment was the frequent change of seating arrangements. Each week, the students were exposed to different types of seating arrangements that included pair seating, change of pair, group seating, U-shape seating, double U-shape seating, circle shape seating, etc. To do this smoothly, the teacher collected a name card from each student in the first week of the term. This name card was used throughout the treatment to assign the seat to the students. The teacher randomly placed this name card on different tables before the class started. Each week, the students were instructed to find their name cards and seat accordingly for two consecutive classes (Monday and Wednesday). While grouping or pairing students, the teacher made sure that none of the group or pair consisted of only dominant or passive students (Storch, 2002). And, the disruptive behavior that students exhibited in the classroom during the treatment (post-intervention, hereafter) from each meeting was recorded using the checklist (See Appendix).

Step 3. The average of post-intervention data was then compared with the pre-intervention data to find out to what extent the intervention strategy used in this study helped reduce students’ improper behavior in the language classroom.

Step 4. Furthermore, ten of the 32 students (five males and five females) were randomly selected a week after the intervention for the semi-structured interview to explore their perceptions about disturbing behavior in the classroom. Each student was interviewed for seven to ten minutes in the English language. The data from each student were recorded for thematic analysis following the guidance of Braun and Clarke (2006). The analysis included, transcribing, coding, collating, checking themes, generating clear names for themes, and finally compiling extracts of interviews to answer the research objectives. First, transcripts from interviews were evaluated and analyzed to identify potential common themes. The derived/potential themes from the participants’ responses were further refined by researchers during multiple readings. Finally, a few themes were identified that best-fit participants’ responses to the perception about disruptive behavior in the classroom.

Observation

This study employed a qualitative AR method. Data collection involved a naturalistic type of observation and semi-structured interviews carried out after the intervention. The naturalistic observation allowed researchers to observe students in their everyday context/environment. This enhanced construct validity of collected data in identifying the common disruptive behavior in the language classroom (Debreli & Ishanova, 2019). All observations were done using a set of weekly checklists designed by the researchers (See Appendix).

After completing the observations, students were interviewed on their perceptions of classroom disruption. The interview was done to understand in-depth views of how students view undisciplined behavior when they see their friends exhibit it in the classroom. Following this, the findings were discussed and reported in this paper for future implications.

The conceptual framework of this study

A brief conceptual framework of the study is presented below in figure 2..

Figure 2: Conceptual framework of the study

Data collection and analysis

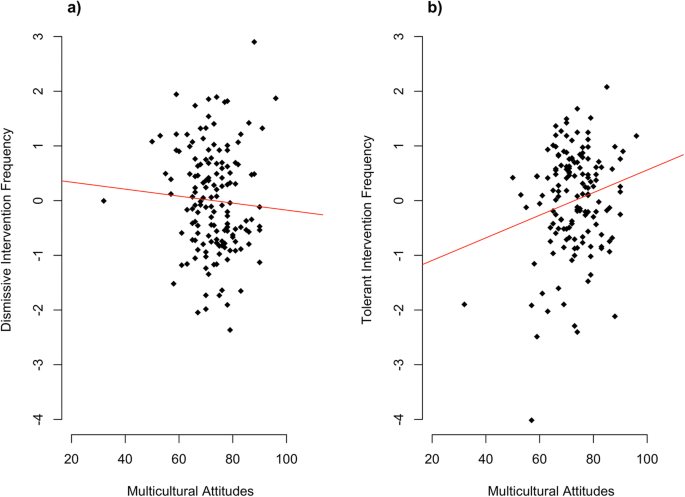

Figure 3: The most common types of disruptive behavior

Figure 3 illustrates the number of students in the percentage who exhibited disruptive behaviors in the English language classroom. The pre-observation data which was carried out to investigate the common types of disruptive behaviors that the participant exhibits in the language classroom revealed six common types of disruptive behavior namely, looking outside the window (25%), coming late to the classroom (28.1%), talking with their friends (37.5%), laughing/shouting out loud in the classroom (43.8%), drawing unrelated pictures (25%), and shifting from one chair to another in the classroom (28.1%).

Figure 4: Comparison between pre-and post-intervention data on disruptive behaviors exhibited by the participants

Figure 4 demonstrates the comparison of disruptive behaviors that the participants exhibited before (pre-intervention) and while in the treatment (post-intervention). The pre-and post-intervention data were compared to examine whether or not the frequent change of seating arrangements had any influence in reducing students’ disruptive behaviors in the classroom. The result revealed that the number of disruptive behaviors that the participants exhibited before the intervention is comparatively higher than that of while in the treatment. For instance, looking out of window was reduced from 25 % of students to 15. 6% after the intervention. Similarly, the number of students coming late to the classroom got reduced by 9.3%, talking in the classroom got reduced by 12.5%, laughing and shouting in the classroom declined by 15.7%, drawing unrelated pictures by students got reduced by 6.2%, and finally the movement of students in the classroom were reduced by 12.5%. On the whole, the result indicated a positive influence of the frequent change of seating arrangements in reducing students' disruptive behaviors in the language classroom.

The semi-structured interviews which aimed at exploring students’ perceptions about disruptive behavior in the classroom gave the researchers a few themes that would be useful in mainstream education. The following themes/categories were revealed in participants’ responses to the interviews, in particular, included disruptive behavior in the classroom impedes learning as students get distracted and disturbed; both teachers and students are responsible for disruptive behaviors in the classroom, teachers’ role in reducing students’ disruptive behavior. Pseudonyms such as S1. S2…S10 were used to represent participants and some excerpts related to the themes/categories were given under each theme.

Theme 1 : Disruptive behavior in the classroom impedes learning as students get distracted and disturbed.

Three students (S1, S6, S8) reported that disruptive behavior in the classroom impeded their learning. They pointed out that when their friends behaved disruptively in the classroom, they lost the track of the lesson, diverted their attention away from the teacher, and sometimes could not hear the teachers properly. One student (S7) even expressed the frustration of not being able to understand teachers’ instructions and lectures because of the presence of disruptive behavior in the classroom.

When my friends show disruptive behavior it diverts my attention which affects my learning. (S1)

I get disturbed and I lose the lesson track when my friends misbehave in the middle of the lesson. (S6)

I get distracted from my study. I feel angry as I cannot hear the teacher properly. (S7)

Two participants (S3, S5) commented that they get distracted and disturbed when their friends exhibit disruptive behavior in the classroom. S9 pointed out that discipline issues in the classroom not only disrupt individuals but the whole class. Likewise, S10 asserted that she does not like when her friends behave disruptively in the classroom because she cannot concentrate on her learning. She pointed out that she loses interest in the lesson.

I often get distracted when a friend shows disruptive behavior. Sometimes, I even cannot focus on my studies. (S3)

Whenever I try to give my full concentration in class, I get distracted when they show disruptive behavior. (S5)

I don’t like to be in the classroom where students exhibit disruptive behavior because I cannot concentrate on what the teacher teaches us and after that, I lose interest in studying. (S10)

Theme 2: Both teachers and students are responsible for disruptive behaviors in the classroom

Two participants (S6, S8) pointed out that teachers were responsible for students’ disruptive behavior in the classroom.They stated that teachers should guide students concerning discipline issues and come up with different methods, such as group discussion where students remain engaged:

I think teachers are responsible for their behavior and some students are responsible as well. Teachers can guide them and use a different method to engage them in studying by group discussion and assigning group work. (S6)

It is teachers’ responsibility to correct their behavior. It is difficult for them to change. (S8)

On the other hand, some of the students (S2, S3, S4, S10) admitted that students were responsible for disruptive behavior in class. They said that students should seek help from teachers and parents and help themselves to improve their discipline in the classroom.

Yes, we are responsible for our behavior. We can improve it by taking the advice of our teachers and parents. We can also look upon our friends who possess good behavior. (S2)

Yes, they are responsible for their behavior. They should seek help to improve it. (S3)

Yes, they can improve their behavior if they follow the instruction given by a teacher or if they do something valuable, they may change the way they behave in class. (S4)

Yes, our behavior must be controlled by ourselves. Maybe a teacher can play an important role to get the students on right track by advising the students frequently. (S10)

Theme 3 : Teachers role in reducing students ’ disruptive behavior

All students who participated in this study believed that the teacher had full control over disruptive behavior in the classroom. Some students (S1, S4, S8) suggested that disruptive behavior of students could be reduced to a certain extent if teachers set rules at the beginning of the class with clear consequences agreed upon if the rules are breached.Additionally, S2 and S9 commented that the teaching methods should be student-centered and be more engaging.

If a teacher sets certain rules that no one should show disruptive behavior, if they happen to break rules then they will get punished. This might help to improve the discipline in the class of the students in the classroom. (S1)

Keep note of students with disruptive behavior. Develop different means of approaching them. Make them engage by using different teaching methods. Give feedback and guidance. (S2)

This study investigated the common types of disruptive behavior that EFL students exhibit in the English language classroom. It examined whether the intervention strategy used in this study help reduce students’ disruptive behavior in the classroom, and explored students’ perceptions of disruptive behavior in the classroom.

This research project revealed six common types of disruptive behaviors that students exhibit while in the English language classroom. We observed that students misbehave especially when they were disinterested and did not understand the subject matter well. This finding was in line with Jati et al. (2019) which claimed that students show disruptive behaviors when they are less interested to learn and face difficulties understanding the subject being taught. The findings also revealed that students’ disruptive behavior can be reduced to a certain extent by implementing different types of seating arrangements in the classroom (Rafi et al., 2020). More so, we also noticed that frequent changes of seating arrangements excite students and make them curious about their seats, seat partners, group members, etc. This improves their motivation to come to class. Of many seating arrangements implemented in this study, the most effective way to reduce disruptive behavior was making students sit in pairs or groups of three or four. This should be however followed by group activities to keep students engaged. Another benefit of seating in pairs or groups is that it helps students facilitate and complement each other in completing assigned tasks in the classroom and gives students more space to communicate with their peers (Alfares, 2017). This also promotes social relationships among the students. Furthermore, we observe that pairing or grouping students increase students’ participation in the classroom(Egounléti et al., 2018). They tend to participate more actively to help their group complete the assigned task. That said, teachers are suggested to be careful when switching group members to avoid only dominant or only passive patterns of the group (Storch, 2002).

As for perception, our findings resonate with earlier studies (e.g., Duesund & Ødegård, 2018; Gómez Mármol et al., 2018; Närhi et al., 2017; Nash et al., 2016) which claimed that disruptive behavior in the classroom is one of the biggest issues in educational settings. We noticed that when students behaved disruptively in the classroom, it negatively impacted the classroom environment, students learning, and teachers’ instruction. In addition, in the interviews, many students commented that when their classmates' misbehaved in the classroom, they got distracted, lost interest in learning, lost attention, and also lost track of the lesson. All together, disruptive behavior of students in the classroom was found disturbing not only by teachers but also by students themselves in this context.

Our findings also revealed that the cause of disruptive behavior in the classroom was attributed to both teachers' classroom management skills and students' behavior. In the interviews, participants reported that teachers had full control over students' behavior in the classroom and they should know how to manage the classroom. The participants suggested that teachers should give proper guidance, advice, and come up with better teaching methods or set strong classroom rules at the beginning of the class with clear consequences to keep students in control. That being said, many students also agreed that students were the major contributor to indisciplined action in the classroom. They pointed out that students should seek advice from teachers and parents and look up to those classmates with good/model behavior and improve their behavior.