Please contact the OCIO Help Desk for additional support.

Your issue id is: 4041237468874644762.

Black Power

Although African American writers and politicians used the term “Black Power” for years, the expression first entered the lexicon of the civil rights movement during the Meredith March Against Fear in the summer of 1966. Martin Luther King, Jr., believed that Black Power was “essentially an emotional concept” that meant “different things to different people,” but he worried that the slogan carried “connotations of violence and separatism” and opposed its use (King, 32; King, 14 October 1966). The controversy over Black Power reflected and perpetuated a split in the civil rights movement between organizations that maintained that nonviolent methods were the only way to achieve civil rights goals and those organizations that had become frustrated and were ready to adopt violence and black separatism.

On 16 June 1966, while completing the march begun by James Meredith , Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) rallied a crowd in Greenwood, Mississippi, with the cry, “We want Black Power!” Although SNCC members had used the term during informal conversations, this was the first time Black Power was used as a public slogan. Asked later what he meant by the term, Carmichael said, “When you talk about black power you talk about bringing this country to its knees any time it messes with the black man … any white man in this country knows about power. He knows what white power is and he ought to know what black power is” (“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press’”). In the ensuing weeks, both SNCC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) repudiated nonviolence and embraced militant separatism with Black Power as their objective.

Although King believed that “the slogan was an unwise choice,” he attempted to transform its meaning, writing that although “the Negro is powerless,” he should seek “to amass political and economic power to reach his legitimate goals” (King, October 1966; King, 14 October 1966). King believed that “America must be made a nation in which its multi-racial people are partners in power” (King, 14 October 1966). Carmichael, on the other hand, believed that black people had to first “close ranks” in solidarity with each other before they could join a multiracial society (Carmichael, 44).

Although King was hesitant to criticize Black Power openly, he told his staff on 14 November 1966 that Black Power “was born from the wombs of despair and disappointment. Black Power is a cry of pain. It is in fact a reaction to the failure of White Power to deliver the promises and to do it in a hurry … The cry of Black Power is really a cry of hurt” (King, 14 November 1966).

As the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and other civil rights organizations rejected SNCC and CORE’s adoption of Black Power, the movement became fractured. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Black Power became the rallying call of black nationalists and revolutionary armed movements like the Black Panther Party, and King’s interpretation of the slogan faded into obscurity.

“Black Power for Whom?” Christian Century (20 July 1966): 903–904.

Branch, At Canaan’s Edge , 2006.

Carmichael and Hamilton, Black Power , 1967.

Carson, In Struggle , 1981.

King, Address at SCLC staff retreat, 14 November 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, “It Is Not Enough to Condemn Black Power,” October 1966, MLKJP-GAMK .

King, Statement on Black Power, 14 October 1966, TMAC-GA .

King, Where Do We Go from Here , 1967.

“Negro Leaders on ‘Meet the Press,’” 89th Cong., 2d sess., Congressional Record 112 (29 August 1966): S 21095–21102.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Suggested Results

Antes de cambiar....

Esta página no está disponible en español

¿Le gustaría continuar en la página de inicio de Brennan Center en español?

al Brennan Center en inglés

al Brennan Center en español

Informed citizens are our democracy’s best defense.

We respect your privacy .

- Analysis & Opinion

‘Black Power’ and the Year that Changed the Civil Rights Movement

In 1966, a dramatic challenge arose against the nonviolent philosophy of Martin Luther King Jr. and John Lewis.

- Mark Whitaker

In February 2023, the Brennan Center hosted a talk in New York with journalist and author Mark Whitaker and Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist Eugene Robinson. Whitaker discussed his book, excerpted below, Saying It Loud: 1966—The Year Black Power Challenged the Civil Rights Movement . You can watch the full conversation here .

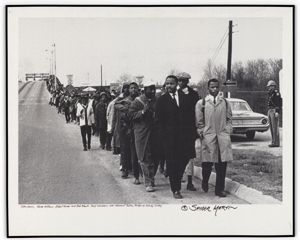

In the middle of Alabama, U.S. Route 80, the highway that links Selma and Montgomery, narrows to two lanes as it passes through Lowndes County, deep in the former cotton plantation territory known as the Black Belt. For decades, the deadly reach of the Ku Klux Klan made this slender stretch of open road, surrounded by swamps and spindly trees covered with Spanish moss, one of the scariest in the South. During the historic civil rights march between those two cities in 1965, fewer than three hundred protesters braved the Lowndes County leg, whispering as they hurried through a rainstorm about rumors of bombs and snipers lurking out of sight. When the march ended, cars transporting demonstrators back to Selma drove as fast as they could through Lowndes County, without stopping.

One car didn’t make it. Viola Liuzzo was a thirty-nine-year-old mother of five from Detroit who had answered the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.’s call for whites to join the Selma march. After it was over, she was helping drive marchers back from Montgomery along with a young Black volunteer named Leroy Moton. As the two headed back to Montgomery after a drop-off in Selma shortly after nightfall, a red-and-white Chevrolet Impala pulled alongside Liuzzo’s blue Oldsmobile on Route 80. A spray of bullets exploded into the driver’s side window, and the car careened off the road and into a ditch. Moton passed out, and when he came to Liuzzo was slumped lifeless on the bench front seat, her foot still on the accelerator.

Moton raced through the darkness to report the attack—which, it would soon emerge, was carried out by four Alabama Klansmen, one of them a paid informant for the FBI.

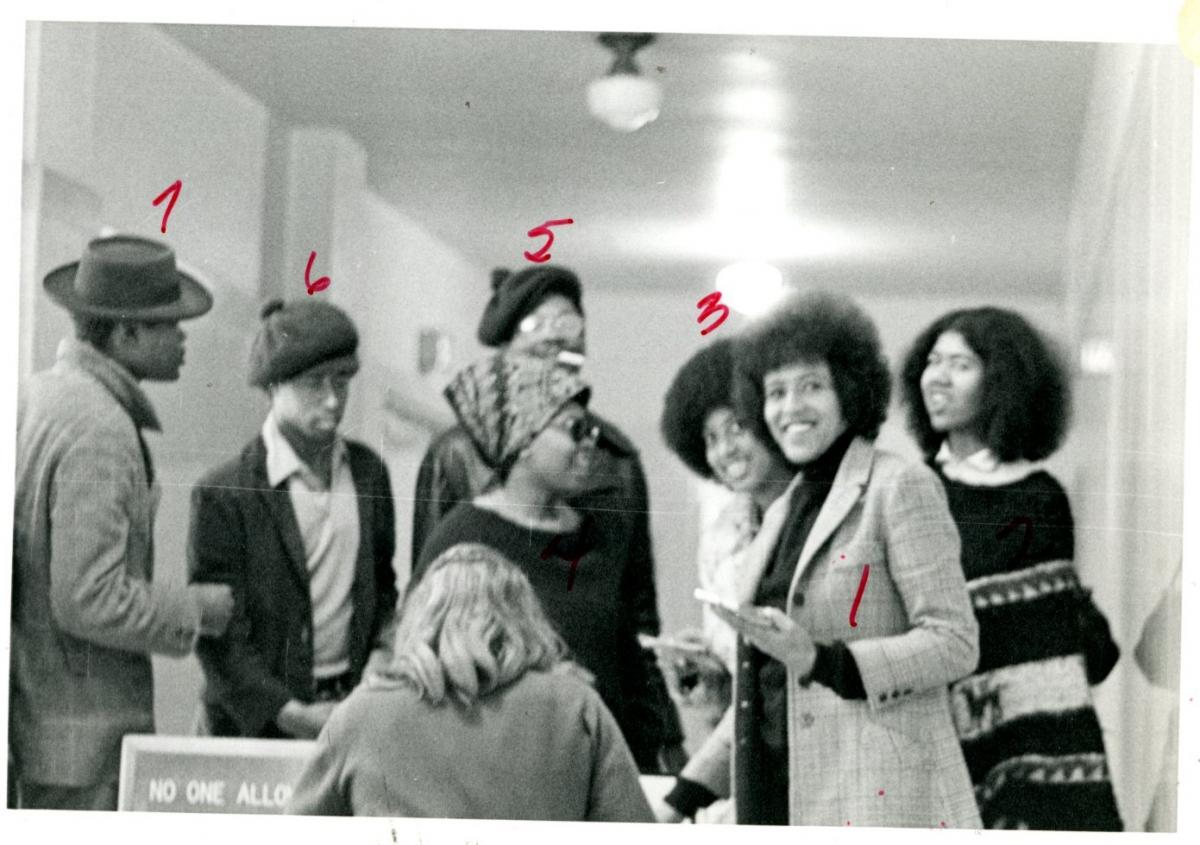

Two days later, as newspapers across the country ran front-page updates on the murder of the first white woman to die in the civil rights struggle, five young Black organizers from the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee slipped unnoticed into Lowndes County on Route 80. The five were there to bring SNCC’s mission of voter registration to the county, an impoverished backwater with the largest percentage of Black residents in the state, but where not a single Black had cast a ballot in more than sixty years. The group’s leader was Stokely Carmichael, a lanky New Yorker with a long, angular nose and heavy-lidded but expressive eyes. His voice mixed the lilt of Trinidad, where he lived until age eleven; the urgency of the Bronx, where he spent his teens; and the polish of Howard University, the distinguished historically Black college from which Carmichael graduated. Over the next eight months, SNCC organizers proved successful enough that white farmers punished Black sharecroppers who registered to vote by evicting them from their land. So it was that, as the year 1965 ended, Carmichael and his comrades found themselves back along Route 80, erecting tents for displaced families while sharecroppers armed with hunting rifles kept watch for night-riding Klansmen.

On the second to last day of December, Carmichael was putting up tents on a six-acre plot that a local church group had purchased by the side of Route 80 when a blue Volkswagen Beetle drove up. A thin, mocha-skinned young Black man dressed in denim overalls stepped out of the car. Carmichael recognized Sammy Younge, a student at Alabama’s Tuskegee Institute who had become active in campus organizing. Over the previous year, Younge had participated in several SNCC protests, and the two men had become friends. But the last time Carmichael had seen the young collegian, at a birthday party Younge threw for himself in November, he had experienced a change of heart. Drunk on pink Catawba wine, Younge cornered Carmichael and confessed that he was through with activism and wanted to return to partying and preparing for a comfortable middle-class career. Younge “was high that night, and we had a talk,” Carmichael recalled. “He said he was putting down civil rights . . . and he was going to be out for himself. . . . So I told him, ‘It’s still cool, you know. Makes me no never mind.’”

Now Younge seemed eager to join the struggle again. “What’s happening, baby?” Carmichael said, greeting the student with his usual teasing ease. “I can’t kick it, man,” Younge said, referring to the organizing bug. “I got to work with it. It’s in me.” Carmichael chatted with Younge for several minutes, then invited him to stay overnight to help with the tent construction. The next day, Younge approached Carmichael again and confided a new dream. He wanted to attempt in Tuskegee’s Macon County what Carmichael was trying to do in Lowndes County: register enough Black voters so they could form their own political party and elect their own candidates to local offices.

In Carmichael’s territory, that fledgling party already had a name: the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO). It also had a distinctive nickname: the “Black Panther Party,” after a symbol that the LCFO had adopted to comply with an Alabama law requiring that political parties choose animal symbols that could be identified on ballots by voters who couldn’t read. “Well, all you have to do is talk about building a Black Panther Party in Macon County,” Carmichael counseled. “See how the idea will hit the people and break that whole TCA thing,” he added, dismissively referring to the Tuskegee Civic Association, a group of elders who had long claimed to speak for Macon County Blacks. Then Carmichael gave Younge a last word of encouragement. “My own feeling was that it would,” Carmichael recalled saying, before he watched Younge climb into his Volkswagen and drive back to Tuskegee.

Although neither Younge nor Carmichael knew it at that moment, they were both about to become major players—one, as a martyr; the other, as a leader and lightning rod—in the most dramatic shift in the long struggle for racial justice in America since the dawn of the modern civil rights era in the 1950s. Over the following year, the story would stretch from Route 80 in Lowndes County across the United States. It would unfold to the east, in that bastion of the Black privilege in Tuskegee; to the northeast, in SNCC’s home base of Atlanta; and due west, on another highway linking Memphis, Tennessee, and Jackson, Mississippi.

To the north, the story would involve a slum neighborhood of Chicago that the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. would select as his next battlefront. Far to the west, two part-time junior college students from Oakland, California, would take inspiration from the black panther experiment in Alabama to launch a radical new movement of their own. After a decade of watching the civil rights saga play out in the South, a restless generation of Northern Black youth would demand their turn in the spotlight. Before the year 1966 was over, the story would alter the lives of a cast of young men and women, almost all under the age of thirty, who in turn would change the course of Black—and American—history.

Copyright © 2023 by Mark Whitaker. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc, NY.

RSVP for the event here

How Politicians Should Think About Crime

Public safety and fairness are not competing interests.

Ohio’s Legacy of Gerrymandering Could End This November

Ohioans will vote on a constitutional amendment that would establish a citizen-led independent redistricting process to replace the politically driven map-making system.

The First Amendment Doesn’t Create a Right to Bribery

Voting rights are the top priority, contributors, protecting voters and election workers from armed intimidation, georgia’s state election board could undermine election transparency, some good news for donald trump: we already use paper ballots, informed citizens are democracy’s best defense.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- History Unclassified

- History in Focus

- History Lab

- Engaged History

- Art as Historical Method

- Submission Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Join the AHR Community

- About The American Historical Review

- About the American Historical Association

- AHR Staff & Editors

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- < Previous

The Black Power Movement, Democracy, and America in the King Years

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Peniel E. Joseph, The Black Power Movement, Democracy, and America in the King Years, The American Historical Review , Volume 114, Issue 4, October 2009, Pages 1001–1016, https://doi.org/10.1086/ahr.114.4.1001

- Permissions Icon Permissions

T aylor B ranch's A merica in the K ing Y ears stands as a singular achievement in civil rights historiography. Collectively, the trilogy covers the years 1954–1968, the time in which Martin Luther King, Jr. became a national civil rights leader and a global icon for human rights and racial justice. For Branch, King was nothing less than a heroic, race-transcending political leader who fundamentally transformed American democracy through an innovative nonviolent ethos rooted in Gandhism, the African American church, and Judeo-Christian traditions of militantly passive resistance. But America in the King Years is more than a conventional biography of King. The trilogy presents a panoramic portrait of postwar America during the civil rights movement's heroic age. Branch documents the activities of rural and urban black leaders, white volunteers and clergymen, and far-flung personalities engaged in political struggles away from the center of media attention. Unglamorous local leaders, obscure sharecroppers, religious scholars, street speakers, and ordinary citizens thrust into the maelstrom of the era receive varying degrees of attention throughout. 1

America in the King Years particularly revels in finely grained portraits of the presidents and powerbrokers whose iconography continues to shape the public's historical memory of this period. Figures such as John F. Kennedy, Robert F. Kennedy, and Lyndon B. Johnson loom large in the proceedings, as does King's ability to move back and forth, at times almost effortlessly, between America's political elites and its racial underclass. Branch's trilogy thus weaves together social and political history to produce a striking historical tapestry that greatly enriches contemporary understanding of the modern civil rights era. 2

Professional historians have, for the most part, been relatively silent regarding Branch's work. David Garrow's Pulitzer Prize–winning study of King, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference , covers roughly the same chronology as Branch's trilogy, with the economic prose and restrained analysis of the trained social scientist. Published in 1986, two years before the first of Branch's three volumes appeared, Bearing the Cross remains probably the most often cited authoritative historical work on King and the modern civil rights movement. Similarly, Adam Fairclough's important 1987 study, To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. , is a more familiar and comfortable reference work for most scholars. 3

As popular history, America in the King Years has achieved the kind of critical acclaim and high profile among the general public that more conventional civil rights scholarship has yet to attain. Written in page-turning prose and organized around dramatic historical scenes, it turns the civil rights era into a gripping drama that pares down world historic events to a human scale. Although King is the trilogy's main narrative anchor, Branch seeks to document the major and minor events of the civil rights era at the local, national, and international level. On this score, America in the King Years is perhaps the most boldly imaginative history of the postwar civil rights era ever conceived.

O n the subject of B lack P ower , America in the King Years hews closely to the conventional script and the received historical and political wisdom that casts the movement as politically naive, largely ineffectual, and ultimately stillborn. Black Power is most often remembered as the civil rights era's ruthless twin, an evil doppelganger that provoked a white backlash, engaged in thoughtless acts of violence and rampaging sexism and misogyny, and was brought to an end by its own self-destructive rage. A wave of new historical scholarship, however, is challenging this perspective, arguing that Black Power ultimately redefined black identity and American society even as it scandalized much of the nation. These new works combine critical analysis and prodigious archival research to historicize the Black Power era and its relationship to civil rights and wider currents of postwar American society. 4

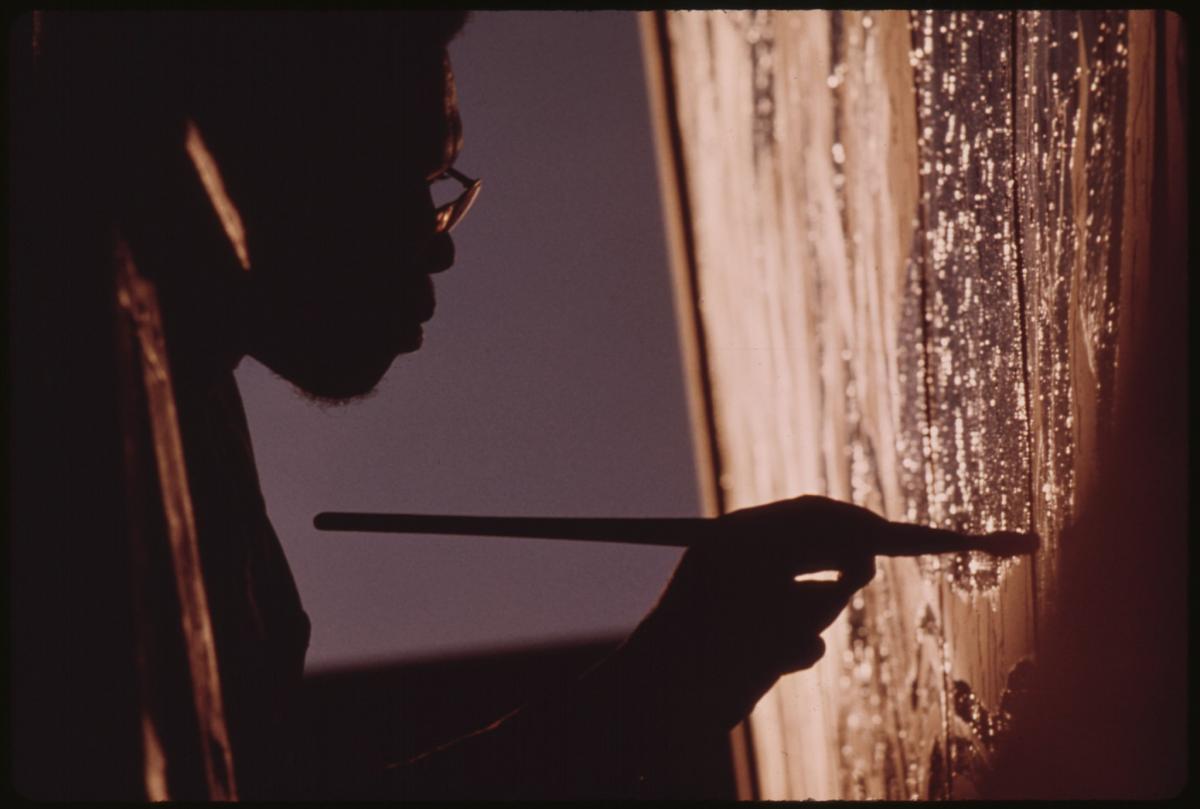

Black Power transformed struggles for racial justice by altering notions of identity, citizenship, and democracy. 5 Its practical legacies can be seen in the first generation of black urban political leaders who, thanks to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, leveraged black voting power through nationalist appeals for racial solidarity in major metropolitan centers; in the cultural impact of the black arts through poetry, the spoken word, independent schools, and dance, theater, and art; in the advent of Black Studies programs and departments at predominantly white universities across the United States; in the proliferation of black student unions on college campuses; and, finally, in a series of political conventions and conferences that crafted do-mestic and international agendas for racial, social, and economic justice. 6 The sheer breadth of the movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s encompassed virtually every facet of African American political life in the United States and touched the international arena as well. Black sharecroppers in Lowndes County, Alabama, urban militants in Harlem, radical trade unionists in Detroit, Black Panthers in Oakland, California, and feminists across America all advocated a political program rooted in aspects of Black Power ideology. A broad range of students, intellectuals, poets, artists, and politicians followed suit, turning the term “Black Power” into a generational touchstone that evoked hope and anger, despair and determina-tion. 7

Violence is crucial to understanding the Black Power years in the United States. The political rhetoric of Malcolm X and his forceful advocacy of self-defense and physical retaliation in the face of violence against civil rights workers set the stage for the movement's complicated relationship with violence. After Malcolm's death, both Stokely Carmichael and the Black Panther Party (originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense) deployed provocative rhetoric that threatened domestic racial upheavals in the face of continued economic misery and social injustice. By the late 1960s, with the proliferating civil disturbances and clashes between urban militants and law enforcement agencies, the Black Power era was to some extent contoured by violence. But while most Black Power organizations retained the right to self-defense, only a small number of groups, most notably the Black Panther Party, openly advocated proactive revolutionary violence.

Parting the Waters , the first volume of America in the King Years , ignores the activities of black radicals. With barely a mention of Malcolm X, Branch reinforces the notion that black radicalism did not erupt until after 1960. America in the King Years has been instrumental in popularizing the civil rights movement's “heroic period.” 8 Roughly comprising the decade between the Supreme Court's decision in the Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case on May 17, 1954, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act on August 6, 1965 (and sometimes extended to 1968, the year in which the Open Housing Act was passed and King was assassinated), this period has come to represent the high tide of nonviolent social unrest in the postwar era. Its familiar cast of characters is led by the ubiquitous King and largely precludes the appearance of black militants. Malcolm X is the single exception in this regard; usually viewed as King's polar opposite, he is presented here as a tragic figure, doomed to an untimely death that was partially of his own making.

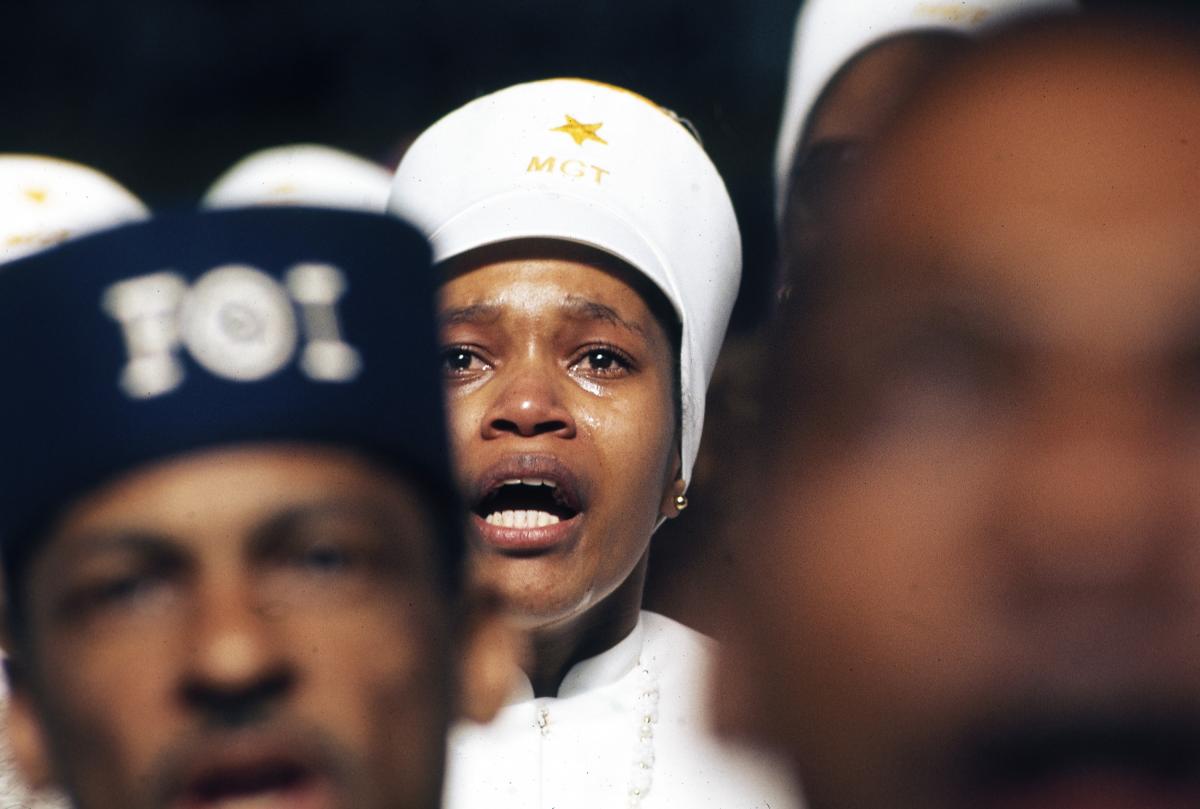

Pillar of Fire , the second volume in the trilogy, devotes considerable attention to Malcolm X, picking up the threads of his story in April 1962 in the aftermath of a police shooting that left Los Angeles Muslim Ronald Stokes dead. Branch portrays Malcolm as an intelligent, highly adaptable leader struggling to build a movement amid growing national and sectarian violence. He offers valuable insights into the inner workings of the Nation of Islam, especially in the aftermath of Malcolm's break from the group, which resulted in his assassination on February 21, 1965.

Yet Malcolm's presence serves primarily to enrich King's stature. Branch's mostly sympathetic portrait of Malcolm views him principally as a brilliant public speaker who was angered by the inability of civil rights leaders to offer more robust solutions beyond sit-ins, marches, and boycotts. He is depicted as less a political leader than a charismatic icon who unleashed words of fire that illustrated the limits of Black Muslim orthodoxy as well as his own inability to proactively ignite the revolution he so often predicted. 9

I f K ing's story highlights the ultimate resilience of democracy, America during the arc of Malcolm X's political career imparts equally important lessons about issues of race, violence, poverty, and democracy that continue to resonate. Malcolm, in many ways Black Power's most enduring symbol, serves as a powerful metaphor for black activism and American democracy in the postwar era. Like most writers of this era, Branch views Malcolm as a compelling but ultimately tragic figure. Tellingly, Malcolm's grassroots political organizing, supple political instincts, and brilliant intellectual analysis of race, democracy, and U.S. domestic and foreign policy recede to the background. His relationship with civil rights–era radicals is rendered invisible at the expense of a more complicated portrait of the times. Hard divisions between the groups involved have allowed the civil rights movement to be hailed as the harbinger of important democratic surges and Black Power to be portrayed as a destructive, at times blatantly misguided movement that promoted rioting over political legislation, violence over diplomacy, and racial separatism over constructive interracial engagement. Embedding civil rights and Black Power activists in their historical context alters this portrait. The two groups may have occupied distinct branches, but they are part of the same historical family tree. 10

Malcolm X arrived in Harlem in 1954, the same year the Supreme Court handed down the Brown decision, and he quickly emerged as a powerful local leader whose appeal transcended the sectarianism of the Nation of Islam. Pushing the origins of the Black Power movement to 1954, the year Malcolm took over the Nation of Islam's Temple No. 7 in Harlem, both complicates and enriches historical understanding of the civil rights and Black Power eras. In the historical context that emerges, civil rights activists and early Black Power militants exist side by side within a political landscape bound by the constraints of the Cold War, yet simultaneously emboldened by upheavals in Africa, Latin America, and the larger Third World. Black Power, like the modern civil rights movement, emerged out of the hotbed of global political struggles that marked the postwar world. 11

Tapping into the lower frequencies of the postwar era provides us with glimpses of a panoramic black freedom struggle in which Black Power militancy paralleled, and at times overlapped with, the heroic period of the civil rights era. Early Black Power activists were simultaneously inspired and repulsed by the struggles for civil rights in the Deep South that riveted the nation and much of the world during the 1950s and early 1960s. Malcolm X crafted coalitions that stretched from New York to Los Angeles during the 1950s, and in the process he helped to nurture centers for radical black political activism. Advocating political self-determination, racial pride, and the relationship between African Americans and the Third World, northern black militants set out to reshape American democracy. Around this same time, NAACP activist Robert F. Williams captured international attention, engaging in a sharp dialogue with King about the merits of nonviolence versus self-defense. 12 In 1961, militants in New York City, including LeRoi Jones and Maya Angelou, staged raucous demonstrations at the United Nations to protest the murder of Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Republic of the Congo. That same year, black college students in Ohio formed what would become the Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM), a group that anticipated aspects of the Black Panther Party's call for an armed political revolution. In Detroit, radicals formed the Group on Advanced Leadership (GOAL), hosted Malcolm X during his frequent visits, and staged militant protests against urban renewal plans.

Taking part in demonstrations, rallies, and bruising protests that focused on bread-and-butter issues such as education, housing, and employment, early Black Power activists regarded Malcolm X as the national spokesman for an unnamed movement that both diverged from and intersected with conventional civil rights struggles. 13 Perhaps the most striking example is the June 23, 1963, “Freedom Walk” in Detroit. Organized as a sympathy march in support of civil rights efforts in Birmingham, it featured King as the keynote speaker and local radicals such as Albert Cleage, a minister and Malcolm X ally who had helped organize the demonstration. The march was a huge success, drawing an estimated crowd of 125,000. The minister of the Central Congregational Church and an activist who participated in both conventional civil rights struggles and more confrontational tactics, Cleage shared King's belief in the social gospel. Even Malcolm X, so often situated as King's diametric opposite, critically engaged the very idea of American democracy in numerous speeches and interviews. At the founding rally for the Organization for Afro-American Unity on June 28, 1964, Malcolm went so far as to hold up the Constitution and the Bill of Rights as personifying “the essence of man-kind's hopes and good intentions.” 14 In truth, a generation of Black Power activists came of age and gained their first taste of organizing during the high tide of the modern civil rights movement from 1954 to 1965. Ranging from the iconic to the obscure, those activists fit outside the master narrative of our national civil rights history. 15

T he decade after the passage of the Voting Rights Act witnessed massive, at times brutally disruptive democratic impulses that continue to defy historical explanation and pat analysis. The rawness of this political explosion was embodied in the Black Power movement. Although it was in 1966 that the cry for “Black Power” broke through the commotion of everyday politics, the sentiment behind the slogan preceded Stokely Carmichael's defiant declaration. Even before there was a group of self-identified “Black Power” activists, African American radicals—represented by the likes of Paul Robeson, Lorraine Hansberry, Malcolm X, Robert Williams, Gloria Richardson, and William Worthy—were working alongside civil rights activists in the black freedom movement. While Black Power activists subscribed to different interpretations of American history, racial slavery, and economic exploitation than their civil rights counterparts, the two movements grew organically out of the same era, and simultaneously inspired, critiqued, and antagonized each other. The assassination of King, the decline of the New Left, urban rebellions, and the end of national civil rights legislation have positioned 1968 as a watershed year that saw the conclusion of the freedom struggles unofficially ignited by Brown .

Careful historical analysis refutes this description. For African American political activists, along with certain sectors of the New Left, the murder trial of Black Panther Party co-founder Huey P. Newton inspired new levels of organizational dedication and community activism. Carmichael's “Free Huey” speeches in Oakland and Los Angeles on February 17 and 18, 1968, galvanized support for the Panthers and helped to turn the group into an international symbol of militancy. Black radicalism grew after 1968, ushering in new waves of cultural militancy, intellectual innovation, political unity, and international awareness that transformed the first half of the 1970s into one of America's most richly tumultuous times. Black Power loomed over the nation in 1968 in ways that are still being chronicled. If anti-war demonstrations, civil rights, and student protests were unpredictable political storms that inter-mittently wreaked havoc on American society, Black Power was a weather pattern whose own internal dynamics impacted and shaped parallel movements for social justice. 16

In short, Black Power is perhaps the least understood of the insurgent social and political movements that are most commonly associated with the 1960s. The Black Power era (1954–1975) remains a controversial and understudied period in American history, yet it is undoubtedly one of the richest periods for historical research. America's Black Power years paralleled the golden age of modern civil rights activism, a period that witnessed the rise of iconic political leaders, broadcast enduring debates over race, violence, war, and democracy, saw the publication of seminal intellectual works, and heralded the evolution of radical social movements that took place against a backdrop of epic historic events. Civil rights and Black Power share a common history, but their stories are usually told separately: whereas the civil rights movement drew from the American democratic tradition, Black Power found kinship in ideas of anti-colonialism and Third World liberation movements. Such a framework is too facile, however, since civil rights activists found hope and inspiration in international political currents and Black Power militants looked to America's sacred democratic texts (such as the Constitution and Declaration of Independence) for a way forward at home.

At Canaan's Edge , the concluding volume of America in the King Years , covers the years 1965–1968, which ushered in the classical phase of the Black Power era (1966–1975). Stokely Carmichael, a SNCC worker who had previously toiled in obscurity as a local organizer in the South, gained national fame after introducing the phrase “Black Power” during the Meredith March in a late spring heat wave in Greenwood, Mississippi. Branch provides sporadic coverage of the movement, in between more elaborate investigations of Lyndon Johnson's increasing obsession with, and eventual disintegration over, the Vietnam War. This is a surprising choice of focus considering the plentiful works on Vietnam and LBJ in comparison to the relatively few authoritative works on Black Power. Branch also details aspects of Carmichael's pre–Black Power activism, most notably in a vital chapter on Lowndes County, Alabama. In rural Lowndes we are able to see Carmichael's sensitive and pragmatic side as he helped to form an independent political party for the county's black residents, the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, in 1965–1966. Adopting a black panther as its emblem, the LCFO was soon being called “the Black Panther Party” by the media—a name that would be adopted in October 1966 by the founders of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, and that would come to provide real and symbolic power for an entire generation. 17 At Canaan's Edge de-picts Black Power as an “extravagant death rattle,” made all the more ironic in Carmichael's case because, according to Branch, he almost casually bartered away six years of heroic field work for the indulgent rhetorical fantasies of a newly crowned celebrity. 18

To be fair, in his description of Carmichael's steadfast activism before the Black Power era, Branch acknowledges the militant leader's grassroots organizing efforts in ways that remain too infrequently cited by others. 19 After 1966, however, Carmichael and the movement he gave a name to become caricatures in At Canaan's Edge , less convincing as real-life figures than as tropes to animate the declension narrative in which the late 1960s are viewed as a freefall into racial violence and disillusionment. Branch's trilogy is sometimes unfairly lumped together with the scores of other “King-centered works,” but in this regard he does parrot the conventional wisdom.

A closer look at C armichael's activism from 1966 to 1968 reveals the legacy of Black Power to be broader, deeper, and more nuanced than its portrayal in At Canaan's Edge suggests. While Carmichael was not the only Black Power leader of his generation, he was arguably the most important. Indeed, at the height of the movement, his activities were under surveillance by a host of local, state, and federal authorities, providing historians with an indispensable portrait of both the activist and the period that shaped him. 20

In 1967, Carmichael embarked on a domestic and international organizing tour that would turn him into a global icon. Black Power was a major theme in U.S. and international politics that year, connecting an entire generation through expressions of combative resistance against war, racism, and poverty. During a whirlwind speaking tour of historically black colleges in the South, Carmichael tested out twin themes, touting Black Power and denouncing the Vietnam War in rapid-fire lectures that roused student bodies from Mississippi to Louisiana. Like a political candidate in an election year, he made his way to both prestigious white universities and obscure black college campuses. According to Carmichael, the black belt in higher education represented a base of untapped power, with resources and skills that could transform living conditions in some of America's poorest communities. SNCC's plans called for banning compulsory military training (“mandatory ROTC”) at black colleges and encouraging student autonomy over outside speakers and curriculum reforms that would include black history and culture. “If we don't get that,” said Carmichael during one speech, “we gonna disrupt the schools.” 21

At elite white universities and private colleges, Carmichael adopted a more professorial mien, giving polished, at times purposefully subdued seminars that combined world history and political philosophy as part of a larger dissection of American democracy. The lecture circuit subsidized a broad-based effort at coalescing the disparate forces committed to the local implications of Black Power. Carmichael's experience as a local organizer had made him aware of the tendency of popular leaders to view politics from on high while barely touching the sacred ground of everyday struggles. Conversely, six months as a national political leader sharpened his attention to the telescopic vision of grassroots activists as well as the heavy burdens of instant celebrity. The philosopher in him viewed Black Power as capable of bridging the gap between black people's local needs and their national ambi-tions.

Perhaps the individual most affected by Carmichael's passionate Vietnam deliberations was Martin Luther King, Jr. In the spring of 1967, King elegantly amplified Carmichael's seasoned anti-war rhetoric in a measured yet resolute speech that sent shock waves around the nation. His April 4 address at New York's Riverside Church lent international stature and moral clarity to the anti-war speeches that Carmichael had been steadily delivering for almost a year. At Riverside, King contrasted Carmichael's bitterness toward the failed promises of American democracy with weary hope. “The world now demands,” he pleaded, “a maturity of America that we may not be able to achieve.” 22 King's words resound today with an authority that began to swell shortly after his Riverside speech. But, as Branch ruefully notes, at the time King found himself in the uncomfortable position of “having to fight suggestions at every stop that his Vietnam stance merely echoed the vanguard buzz of Stokely Carmichael.” 23 He need not have worried. At Canaan's Edge highlights King's peace advocacy as a daring rejection of the status quo, even as it downplays the stridently eloquent anti-war position of Carmichael and SNCC. Like most narrators of the era, Branch posits Carmichael as more a saber-rattler than an organizer by the late 1960s. 24 In retrospect, both King's and Carmichael's anti-war activism drew from a deep reservoir of African American anti-colonial activity rooted in the freedom surges of the Great Depression and World War II years. 25

More pointedly, Branch argues that by 1967, SNCC had devolved into internal bickering and “youthful disputes as tawdry as snipes at clothes,” which represented a steep decline from the glory days when “coordinated sacrifice beyond the wisdom and courage of the nation's elders” moved America closer to racial egalitarianism and equal citizenship. 26 In this sense, Branch contrasts the “good” Carmichael who toiled heroically in the Mississippi Delta and rural Lowndes County in the early 1960s with the “bad” Carmichael who grew increasingly intoxicated by the allure of fame associated with his Black Power rhetoric.

Dubbed the “Magnificent Barbarian” by unnamed admirers in SNCC, Carmichael engaged in political activities during the late 1960s that remain as controversial today as they are misunderstood. What Branch characterizes as Carmichael's “daredevil cry against white America” might be better described as an extension and amplification of the SNCC leader's grassroots political organizing, which dated back to his teenage years in New York City and reached new heights in the late spring of 1961, when he spent weeks in Mississippi's Parchman Farm (the state penitentiary) for participating in Freedom Rides. 27 By 1966, when Carmichael declared “Black Power” in the sticky humidity of a late evening in Greenwood, Mississippi, his comprehension of American politics had become broad, deep, and complex.

“We are trying to build democracy,” wrote Carmichael to SNCC supporter Lorna Smith in a 1966 letter that provided intimate details of painstaking organizing efforts taking place in Lowndes County. His search for democracy in Alabama's harsh climate rested on “the human contact that we make, while suffering,” where black sharecroppers held the key to remaking American society. 28 He elaborated these views in an archly written report of his activities in Lowndes, published in the New Republic that same year. Criticizing Lyndon Johnson's Great Society as “preposterous,” Carmichael offered up the political struggles of the black poor in the rural South as an alternative democratic ethos. In his America, democracy was etched in the faces of the semiliterate sharecroppers who were struggling to “redefine” Great Society rhetoric as a new vision of citizenship. 29 His grueling efforts to dig deep into what King described as the “great wells” of democracy were not abandoned in favor of a rash call for Black Power. For Carmichael, Black Power's call for radical self-determination facilitated the prospects of genuine democracy in American territories as unwelcoming and closed off to the idea of black citizenship as Lowndes County. 30

B ranch's depiction of B lack P ower as a political dead end obscured by polemical fireworks and the brooding charisma of Carmichael, Rap Brown, Huey P. Newton, and other Black Power icons makes for riveting reading at the expense of a more nuanced and comprehensive history. If his portrait of Carmichael remains uneven, his account of the era's most controversial and visible group, the Black Panther Party (BPP), is surprisingly undernourished. The Panthers emerge, like a fever dream, as a group of swaggering leather-jacket-clad militants emboldened by the bravado of the quick-witted, temperamental Huey P. Newton and the earthy Bobby Seale. Amid the growing maelstrom of anti-war protests, Black Power militancy, and urban rebellions, “Newton's instant fame spread romantic theories about revolutionary violence.” 31 At first glance, this point appears unassailable considering the rhetoric of the Panthers and an increasingly radicalized New Left. By all appearances an overnight revolutionary hero, Newton belonged to a generation of young black Americans in Oakland and across the country whose economic prospects would be worse than those of their parents. A juvenile delinquent, street hustler, and brawler, he listened to Malcolm X speak in the Bay Area, joined an early Black Power cultural group called the Afro-American Association, and attended a local community college where he taught himself to read. By the time he co-founded the BPP, he had done several stints in jail and participated in local community organizing. As a political leader, Newton possessed jarring contradictions: advocating peace yet committed to a violent political revolution; anti-drug yet a substance abuser for much of his life; identifying with the poor but enamored with wealth and glamour. His importance as a Black Power leader ultimately resonates when we examine both the organization he helped to create and, perhaps most important, the communities that for a time identified with the BPP. 32

Like Newton, the Panthers exhibited Janus-faced tendencies. One side advocated the belligerent tactics of Third World revolutionaries in a quest to overthrow the existing social, political, and economic order. As is perhaps best expressed in Minister of Information Eldridge Cleaver's inimitable and purposefully bombastic speeches, the Panthers are most often remembered for a posture of self-defense that quickly drifted into full-blown advocacy of revolutionary political violence. 33 Their more compassionate face regaled against poverty, hunger, and deprivation and set out to create ad hoc programs (from free breakfasts for schoolchildren to health clinics and liberation schools) that would fundamentally transform American democracy. Rather than viewing the Panthers as antithetical to the freedom dreams envisioned by King and civil rights advocates, as critics and even some sympathizers frequently do, it might be more useful to see them as proponents of the robust self-determination that Carmichael defined as being integral to Black Power and American democracy. The party's ten-point manifesto, issued in 1966, called, among other things, for full employment, freedom, an end to economic misery in black neighborhoods, decent housing, and comprehensive education. From their inception, the Black Panthers displayed a deft understanding of the effects of crime, violence, and unemployment on the most vulnerable segments of the African American community. Of course, the revolution they confidently predicted did not go off as planned. Internal corruption, youthful egos, substance abuse by key leaders, and an undemocratic leadership style combined with government repression to add equal portions of triumph and tragedy to the group's legacy. However, that legacy deserves, indeed demands, a rigorous historical reassessment in a work as ambitious as America in the King Years .

At Canaan's Edge also fails to explore the relationship between Carmichael and the Panthers. It was Carmichael's organizing in Lowndes County during 1965–1966 that provided the group (and similar organizations that in fact predated the Oakland Panthers) with their name and their militancy. Carmichael met with members of the BPP in 1967 while he was in the Bay Area mentoring neophyte local activists in an attempt to consolidate Black Power in some of America's toughest urban areas.

Carmichael's contacts in Southern California included Maulana Karenga, founder of the Organization Us (whose name literally signified “us blacks”) and a prominent local black nationalist whose influence would spread among more Afrocentric Black Power activists. An early supporter of the “Free Huey Newton” movement, Karenga and the Panthers were engaged in turf wars by 1969 that would turn tragically violent. 34 Bald-headed, loquacious, and canny, Karenga represented Black Power's increasing cultural thrust in the Bay Area. 35 His offbeat brilliance, his love of African culture, and his ritualized expression of racial solidarity rubbed more urbane street toughs the wrong way. Karenga and the Organization Us also underscored the darker side of Black Power through their deep-seated, at times brutal misogyny, their reflexive promotion of violence, and a hierarchical organizational structure that promoted a cult of personality over democratic leadership practices. Overshadowed by the leather-jacketed allure of the Black Panthers, the Organization Us would endure, like jazz, through invented cultural flourishes (in style, language, and the holiday Kwanzaa) that would be adopted by generations of black Americans. 36

At the start of 1967, Carmichael found himself being trailed by ex-convict-turned-journalist (and future Black Panther) Eldridge Cleaver for a story in Ramparts magazine and mediating disputes between militants in the Bay Area eager to be considered the vanguard of California's burgeoning Black Power movement. On May 25, he headlined a fundraiser for the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense at San Francisco's Fillmore Auditorium. Loquacious urban militants denied, by dint of geography and biography, the rich experiences that propelled Carmichael's activism, the Panthers traded bravado for experience, substituting showmanship—complete with shotguns, pistols, and bandoliers—to publicize an embryonic anti-racist agenda that would shortly transform America. Carmichael's slow, patient, radical organizing in obscure Lowndes County gave the Bay Area group distinctly southern roots. The quest of the earlier “Black Panther Party” (as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization had been nicknamed) for radical self-determination through the vote gave the Oakland-based Panthers both their name and their raison d'être. 37 FBI agents, in coordination with the U.S. Department of Justice, shadowed these developments while meticulously documenting Carmichael's numerous speeches at colleges and universities as part of a bulky “Prosecutive Summary”—complete with affidavits—that charged the SNCC chairman with sedition. 38

Stokely's threat to take over Washington “lock, stock, and barrel” through black political control over the nation's capital sent FBI agents, local authorities, and journalists scurrying. The Wall Street Journal dutifully warned Washington of Carmichael's imminent arrival, noting that the news had “the nation's capital … in a sweat.” 39 Such fears proved to be unfounded.

By July, Carmichael was touring the world. His first stop was London, where he shared the dais with radical intellectuals such as Herbert Marcuse. Carmichael proclaimed that American cities would be “populated by peoples of the Third World” who were no longer willing to tolerate cultural degradation and institutional racism. Hailed as the “Mainspring of Black Power” in the London press, he spoke to British audiences of his childhood in Trinidad when it was still under British colonial rule. Draped in African robes, he addressed meetings in Notting Hill, Brixton, and Hackney, where he pondered the continued celebrity of the royal family and described Malcolm X as his “patron saint.” 40 Carmichael's penchant for quoting Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus made good copy for reporters, who alternately portrayed him as a diehard nationalist whose “colour is his country” and a dedicated civil rights activist who “has spent seven of his last eight birthdays in jail.” 41 In London, African and Caribbean militants received him as Malcolm X's youthful heir.

As Carmichael was tossing rhetorical Molotov cocktails from Cuba, American cities were beginning to burn. Sparked by an incident of police brutality, a riot broke out in Newark, New Jersey, during the second week of July, shortly before the start of a planned Black Power conference. In the midst of the upheaval, poet LeRoi Jones received a brutal beating that furthered his resolve to promote black rule in the city. 42 Detroit erupted in an explosion that dwarfed Newark's, accelerating predictions by Black Power activists that an urban revolution was imminent. “It was as if,” wrote reporter Louis Lomax, “God himself was on the side of the organized revolutionaries.” 43 In the Omaha World Herald , Lomax penned a highly speculative account that traced the origins of the Detroit riot to a group of organized Black Power militants, at least one of whom had been on the scene in Newark. Lomax's chronicle characterized looters, police officers, and bystanders as pawns in a political experiment being orchestrated by urban revolutionaries. 44 The story exaggerated the ability of Black Power to organize urban insurrection but accurately reflected the mood of politicians, law enforcement, and a large segment of Americans who correlated riots with radicals.

Hubert Geroid Brown, nicknamed “Rap” for his cogent speaking style, quickly became the media's favorite scapegoat for the riots. With his earthy sense of humor, dark sunglasses, and penchant for outrageous sound bites, Brown projected the image of a revolutionary straight from central casting. As Carmichael toured the Third World, Brown electrified partisan audiences and frightened most Americans, threatening spectacular violence and delivering quotes, such as “Violence is as American as cherry pie,” that would endure long after he faded from the political scene. Brown's rhetorical somersaults at times served as a distraction from the movement's more concrete efforts to organize poor people for bread-and-butter issues such as jobs, good schools, and tenant and welfare rights in favor of cathartic polemics. During Carmichael's absence from the domestic political scene, however, Brown provided a wide range of media with what quickly became the archetypal image of the Black Power militant. 45 In this sense, his celebrity popularized a specific style of radicalism that Branch invokes as a stand-in for the entire era.

A weekend excursion with Fidel Castro in July placed Carmichael in the private company of a revolutionary icon even as elected officials in the United States were openly calling for his arrest on charges of sedition. 46 Washington-based political reporters Rowland Evans and Robert Novak, whose syndicated column was required reading inside the Beltway, alleged that SNCC represented nothing less than “Fidel Castro's arm in the United States.” 47 Breathless FBI reports seemed to confirm such suspicions, with confidential informants suggesting that Carmichael was learning insurrection techniques in Cuba that he planned to use upon his return to the States. 48 Carmichael held up Cuba's revolution as a daring experiment in freedom and outraged American officials by predicting a domestic race war complete with urban guerrillas. In addition to defying the government's embargo, he spent weeks in Havana attending the Organization for Latin American Solidarity Conference, where he was feted as the leader of the black revolution. By early August, the U.S. attorney general had seen enough; he contacted the FBI, “desperately trying to obtain speeches, radio and television tapes” of Carmichael's time in Havana. 49 With Carmichael's trip to Cuba, Black Power had become a global export. Newspapers and wire services in Paris, Algeria, Vienna, Warsaw, Hanoi, and Peking carried excerpts of his radical press statements. From Cuba, Carmichael would trek to a number of other countries, including Vietnam, Algeria, Guinea, and Tanzania, as part of a life-altering tour around the world. 50

C armichael moved permanently to A frica in 1969, just as the Black Power movement he had helped unleash was gaining momentum, touching virtually every facet of American life (from education to the arts, prisons to organized athletics, and welfare rights activists to black elected officials) in a process that would transform U.S. democracy. Long after the verbal polemics of Carmichael and other Black Power icons subsided, the era's legacy remains in the enduring debates over race, violence, citizenship, and democracy that it sparked. Despite its Dickensian sprawl, America in the King Years fails to portray this vital era in all of its confounding and messy complexity.

At Canaan's Edge presents the civil rights movement in rich, vibrant Technicolor. It has unquestionably added nuance and complexity to the historical record that scholars would do well to recognize. At times, however, the brightness of this portrait obscures as much as it reveals. Civil rights and Black Power are consistently represented as dichotomous, separate movements rooted in sharply contrasting traditions. Branch portrays Black Power activists as drawn to a pantheon of international revolutionary heroes and the corresponding flights of fantasy, while civil rights workers form bonds to an earthier and more domesticated vision rooted in traditions of American democracy. The rich tapestry and interconnections between civil rights and Black Power are ignored, for the most part, in favor of a more conventional approach to the era that argues that Black Power's defiant call for robust political self-determination accelerated the decline of the 1960s by frightening white Americans, marginalizing black moderates, and inspiring racial reactionaries in politics that fueled a backlash that thwarted both the movement's short-term goals and its long-term prospects.

In fact, the high tide of Black Power came after 1968, touching multiple aspects of American life: from labor unions and the arts, to high schools, colleges, and universities, to local and national political elections. Civil rights activists drew consistent inspiration from global political upheavals, too, just as Black Power militants found unexpected (and too often unacknowledged) strength in American democracy. The movement's impact spanned local, regional, and national borders and beyond, galvanizing political activists in the Caribbean, Europe, Africa, Latin America, and much of the rest of the world. For scholars discussing Black Power, memory too often serves as a substitute for rigorous historical analysis.

Black Power offered new words, images, and political frameworks that impacted and influenced a wide spectrum of American and global society. The movement's breadth spanned continents and crossed oceans but indelibly shaped local struggles at the grassroots level in urban and rural communities across the nation. Before contemporary discussion of multiculturalism and diversity entered America's national lexicon, Black Power promoted new definitions of citizenship, identity, and democracy that, although racially specific, inspired a variety of multiracial groups in their efforts to shape a new world. In locating the roots of Black Power radicalism among groups of activists who waged political wars in the long shadow of the civil rights movement, historians will not only improve contemporary understanding of postwar American history, but, perhaps more important, allow us to reframe conventional understanding of civil rights struggles and the way in which a broad range of black activists attempted to redefine American democracy. 51

Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954–63 (New York, 1988); Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963–65 (New York, 1998); Branch, At Canaan's Edge: America in the King Years, 1965–68 (New York, 2006).

Academic historians have been reluctant to critically analyze and critique Branch's work. Charles Payne notes the compelling literary qualities of Parting the Waters while criticizing Branch for being an at times too aggressively interpretive chronicler and in certain instances factually incorrect. “He tells a great story,” writes Payne, “but not always the one that happened.” Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (Berkeley, Calif., 1995), 420.

David J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York, 1986). Adam Fairclough criticizes Pillar of Fire for devoting “an inordinate amount of space to Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam”; Fairclough, To Redeem the Soul of America: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Martin Luther King, Jr. (1987; repr., Athens, Ga., 2001), 410. See also Garrow's highly critical review of At Canaan's Edge : “Journey's End,” Los Angeles Times , January 15, 2006, R-4.

Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York, 2006); Joseph, ed., The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights–Black Power Era (New York, 2006); Komozi Woodard, A Nation within a Nation: Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) and Black Power Politics (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1999); Timothy B. Tyson , Radio Free Dixie: Robert F. Williams and the Roots of Black Power (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1999); Scot Brown, Fighting for US: Maulana Karenga, the US Organization, and Black Cultural Nationalism (New York, 2003); Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar , Black Power: Radical Politics and African American Identity (Baltimore, 2004); James Edward Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2005); Matthew J. Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia, 2005); Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton, N.J., 2003); Yohuru Williams, Black Politics/White Power: Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Black Panthers in New Haven (New York, 2000).

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour . See also Black Power , Special Issue, Magazine of History 22, no. 3 (2008).

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour ; Joseph, The Black Power Movement ; Woodard, A Nation within a Nation ; Winston A. Grady-Willis, Challenging U.S. Apartheid: Atlanta and Black Struggles for Human Rights, 1960–1977 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006); Cleveland Sellers with Robert Terrell, The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC , 2nd ed. (Jackson, Miss., 1990); Joy Ann Williamson, Black Power on Campus: The University of Illinois, 1965–75 (Urbana, Ill., 2003); Fabio Rojas, From Black Power to Black Studies: How a Radical Social Movement Became an Academic Discipline (Baltimore, 2007).

On the Black Panther Party, see Charles E. Jones, ed., The Black Panther Party [Reconsidered] (Baltimore, 1998); Kathleen Cleaver and George Katsiaficas, eds., Liberation, Imagination, and the Black Panther Party: A New Look at the Panthers and Their Legacy (New York, 2001); Williams, Black Politics/White Power ; William Van DeBurg, New Day in Babylon: The Black Power Movement and American Culture, 1965–1975 (Chicago, 1992); Ogbar, Black Power ; Curtis J. Austin, Up against the Wall: Violence in the Making and Unmaking of the Black Panther Party (Fayetteville, Ark., 2006); Jama Lazerow and Yohuru Williams, eds., In Search of the Black Panther Party: New Perspectives on a Revolutionary Movement (Durham, N.C., 2006); Yohuru Williams and Jama Lazerow, eds., Liberated Territory: Untold Local Perspectives on the Black Panther Party (Durham, N.C., 2008); Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 205–275; Paul Alkebulan, Survival Pending Revolution: The History of the Black Panther Party (Tuscaloosa, Ala., 2007); Jane Rhodes, Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon (New York, 2007); Donna Murch, “The Campus and the Street: Race, Migration, and the Origins of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, CA,” New Black Power History , Special Issue, Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Identity 9, no. 4 (2007): 333–345. For black feminists during this period, see Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 271–275; Kimberly Springer, Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968–1980 (Durham, N.C., 2005); Springer, ed., Still Lifting, Still Climbing: African American Women's Contemporary Activism (New York, 1999); Bettye Collier-Thomas and V. P. Franklin, eds., Sisters in the Struggle: African American Women in the Civil Rights–Black Power Movement (New York, 2001); Stephen Ward, “The Third World Women's Alliance: Black Feminist Radicalism and Black Power Politics,” in Joseph, The Black Power Movement , 119–144.

Peniel E. Joseph, “Black Power's Powerful Legacy,” Chronicle Review , July 21, 2006, B6–B8.

Branch, Pillar of Fire , 3–20, 78–85, 96–98, 184–186, 200–203, 251–262, 312–320, 328–329, 332, 345–349, 380–381, 384–386, 500–502, 538–540, 572–575.

I refer to this new scholarship as “Black Power Studies.” See Peniel E. Joseph, “Black Liberation without Apology: Reconceptualizing the Black Power Movement” and all the essays in special two-volume issues of The Black Scholar 31, no. 3–4 (2001) and 32, no. 1 (2002). See also Joseph, The Black Power Movement ; and New Black Power History , Special Issue, Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Identity 9, no. 4 (2007).

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 9–34. The new scholarship on the intersection of the Cold War, black internationalism, and American democracy is equally suggestive for scholars and students of Black Power. See, for example, Gerald Horne, Black and Red: W.E.B. Du Bois and the African American Response to the Cold War, 1944–1963 (Albany, N.Y., 1986); Brenda Gayle Plummer, Rising Wind: Black Americans and U.S. Foreign Affairs, 1935–1960 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1996); Penny M. Von Eschen, Race against Empire: Black Americans and Anticolonialism, 1937–1957 (Ithaca, N.Y., 1997); Von Eschen, Satchmo Blows Up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War (Cambridge, Mass., 2005); Thomas Borstelmann, The Cold War and the Color Line: American Race Relations in the Global Arena (Cambridge, Mass., 2001); Mary L. Dudziak, Cold War Civil Rights: Race and the Image of American Democracy (Princeton, N.J., 2000); Carol Anderson, Eyes off the Prize: The United Nations and the African American Struggle for Human Rights, 1944–1955 (Cambridge, 2003); George White, Jr., Holding the Line: Race, Racism, and American Foreign Policy toward Africa, 1953–1961 (Lanham, Md., 2005); Nikhil Pal Singh, Black Is a Country: Race and the Unfinished Struggle for Democracy (Cambridge, Mass., 2004); James H. Meriwether, Proudly We Can Be Africans: Black Americans and Africa, 1935–1961 (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2002); Kevin K. Gaines, American Africans in Ghana: Black Expatriates and the Civil Rights Era (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2006).

Tyson, Radio Free Dixie , 192.

See Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 68–94.

Malcolm X, By Any Means Necessary: Speeches, Interviews and a Letter , ed. George Breitman (New York, 1970), 40.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour ; Joseph, The Black Power Movement ; Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement ; Muhammad Ahmad, We Will Return in the Whirlwind: Black Radical Organizations, 1960–1975 (Chicago, 2007).

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 205–240; Van DeBurg, New Day in Babylon ; Ogbar, Black Power ; Woodard, A Nation within a Nation .

Branch, At Canaan's Edge , 455–479.

Ibid., 494.

Some important exceptions are Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, Mass., 1981); Payne, I've Got the Light of Freedom ; Stokely Carmichael with Ekwueme Michael Thelwell, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York, 2003); Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour .

After Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael is probably the best-documented Black Power activist of his generation. In addition to countless newspaper articles in the black, radical underground, and mainstream press, Carmichael's activities are chronicled in a number of different archival sources, including an almost 20,000-page FBI file. See Peniel E. Joseph, Stokely Carmichael and America in the 1960s (forthcoming).

Federal Bureau of Investigation, Kwame Ture File [hereafter FBIKT], 100-446080-471, transcript of Stokely Carmichael University of Texas Speech, April 13, 1967, 30. ROTC (the Reserve Officers' Training Corps) was a military training program for male students at U.S. colleges and universities.

Branch, At Canaan's Edge , 593.

Ibid., 603.

King had come out against the war as early as 1965 but was quickly pressured into silence. SNCC subsequently became one of the war's leading critics, and from June 1966 to April 1967, Carmichael emerged as the black freedom struggle's most vocal anti-war critic. See Branch, At Canaan's Edge , 254–255, 308–309, 591–597; Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 179–183.

Plummer, Rising Wind ; Von Eschen, Race against Empire ; Anderson, Eyes off the Prize ; Singh, Black Is a Country ; Jacqueline Dowd Hall, “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past,” Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (2005): 1233–1263.

Branch, At Canaan's Edge , 606.

Ibid., 608. For Carmichael's time as a Freedom Rider, see Carmichael with Thelwell , Ready for Revolution ; Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour .

Stokely Carmichael–Lorna D. Smith Collection, 1964–1972 [hereafter SCLDS], Green Library, Stanford University, Stanford, Calif., Stokely Carmichael to Lorna D. Smith, January 15, 1966, 1–4.

Stokely Carmichael, “Who Is Qualified?” The New Republic , January 8, 1966, 22.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour ; Peniel E. Joseph, “Revolution in Babylon: Stokely Carmichael and America in the 1960s,” New Black Power History , Special Issue, Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 9, no. 4 (2007): 281–301; Carmichael with Thelwell, Ready for Revolution .

Branch, At Canaan's Edge , 609.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 207–240.

Ibid., 213–214, 265–267.

Brown, Fighting for US ; Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour .

Van DeBurg, New Day in Babylon ; Brown, Fighting for US ; Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement .

FBIKT, 100-446080-298, “Stokely Carmichael,” June 7, 1967, 1–6.

FBIKT, 100-446080-489, “Stokely Carmichael: Prosecutive Summary,” August 12, 1967, 1–322.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 182.

FBIKT, 100-446080 (no further serial), The Observer Review , July 23, 1967.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 183–185.

FBIKT, 100-446080-466, Omaha World Herald , August 6, 1967.

Ibid., Louis Lomax, “Detroit Proved a Fertile Field for Riot Seed,” Omaha World Herald , August 5, 1967; and Lomax, “Agitators Used Twists of Fate, Human Weakness in Rioting,” Omaha World Herald , August 6, 1967.

Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour , 181–183, 186, 188–190.

FBIKT, 100-446080 (further serial not recorded), Memorandum, August 4, 1967.

FBIKT, 100-446080-466, “Snick—Castro's Arm in U.S.,” Omaha World Herald , August 6, 1967.

FBIKT, 100-446080 (further serial not recorded), “Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee,” August 4, 1967.

FBIKT, 100-446080-498, Memorandum, “Stokely Carmichael, Sedition,” Deke DeLoach to Clyde Tolson, August 7, 1967, 1.

Carmichael with Thelwell, Ready for Revolution ; Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour .

For examples, see Tyson, Radio Free Dixie ; Woodard, A Nation within a Nation ; Williams, Black Politics/White Power ; Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement ; Joseph, Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour ; Rod Bush, We Are Not What We Seem: Black Nationalism and Class Struggle in the American Century (New York, 1999); Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2003); Singh, Black Is a Country ; Rhonda Y. Williams, The Politics of Public Housing: Black Women's Struggles against Urban Inequality (New York, 2004); Williams, “Black Women, Urban Politics, and Engendering Black Power,” in Joseph, The Black Power Movement , 79–103; Lance Hill, The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2004); Countryman, Up South ; Premilla Nadasen, Welfare Warriors: The Welfare Rights Movement in the United States (New York, 2005); Christina Greene, Our Separate Ways: Women and the Black Freedom Movement in Durham, North Carolina (Chapel Hill, N.C., 2005); Felicia Kornbluh, The Battle for Welfare Rights: Politics and Poverty in Modern America (Philadelphia, 2007); Annelise Orleck, Storming Caesar's Palace: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty (Boston, 2006); Simon Wendt, The Spirit and the Shotgun: Armed Resistance and the Struggle for Civil Rights (Gainesville, Fla., 2007); Brown, Fighting for US ; Ogbar, Black Power ; Christopher B. Strain, Pure Fire: Self-Defense as Activism in the Civil Rights Era (Athens, Ga., 2005); Jeanne F. Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, eds., Freedom North: Black Freedom Struggles outside the South, 1940–1980 (New York, 2003); Theoharis and Woodard, eds., Groundwork: Local Black Freedom Movements in America (New York, 2005); Kent Germany, New Orleans after the Promises: Poverty, Citizenship, and the Search for the Great Society (Athens, Ga., 2007); Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights, 1919–1950 (New York, 2008); Thomas J. Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North (New York, 2008); Susan Youngblood Ashmore, Carry It On: The War on Poverty and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama, 1964–1972 (Athens, Ga., 2008); Devin Fergus, Liberalism, Black Power, and the Making of American Politics, 1965–1980 (Athens, Ga., 2009); Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama's Black Belt (New York, 2009).

Peniel E. Joseph is Professor of History at Tufts University. He is the author of the award-winning Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (Henry Holt, 2006) and Dark Days, Bright Nights: From Black Power to Barack Obama (Basic Books, forthcoming 2010), and editor of The Black Power Movement: Rethinking the Civil Rights–Black Power Era (Routledge, 2006) and Neighborhood Rebels: Black Power at the Local Level (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming 2010).

I would like to thank Yohuru Williams, Rhonda Y. Williams, Femi Vaughan, Glenda Gilmore, Jeremi Suri, Wellington Nyangoni, Tom Sugrue, Manning Marable, participants at the Long Civil Rights Movement Conference, and the anonymous readers for the AHR who helped to critically shape the ideas in this essay.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| December 2016 | 1 |

| January 2017 | 5 |

| February 2017 | 18 |

| March 2017 | 18 |

| April 2017 | 10 |

| May 2017 | 10 |

| June 2017 | 2 |

| July 2017 | 4 |

| August 2017 | 18 |

| September 2017 | 15 |

| October 2017 | 9 |

| November 2017 | 19 |

| December 2017 | 23 |

| January 2018 | 54 |

| February 2018 | 22 |

| March 2018 | 13 |

| April 2018 | 30 |

| May 2018 | 29 |

| June 2018 | 2 |

| July 2018 | 4 |

| August 2018 | 6 |

| September 2018 | 5 |

| October 2018 | 14 |

| November 2018 | 18 |

| December 2018 | 10 |

| January 2019 | 14 |

| February 2019 | 9 |

| March 2019 | 17 |

| April 2019 | 10 |

| May 2019 | 4 |

| June 2019 | 6 |

| July 2019 | 7 |

| August 2019 | 7 |

| September 2019 | 8 |

| October 2019 | 10 |

| November 2019 | 19 |

| December 2019 | 8 |

| January 2020 | 20 |

| February 2020 | 13 |

| March 2020 | 14 |

| April 2020 | 22 |

| May 2020 | 18 |

| June 2020 | 18 |

| July 2020 | 19 |

| August 2020 | 83 |

| September 2020 | 40 |

| October 2020 | 52 |

| November 2020 | 32 |

| December 2020 | 41 |

| January 2021 | 26 |

| February 2021 | 34 |

| March 2021 | 63 |

| April 2021 | 60 |

| May 2021 | 52 |

| June 2021 | 11 |

| July 2021 | 21 |

| August 2021 | 92 |

| September 2021 | 78 |

| October 2021 | 37 |

| November 2021 | 47 |

| December 2021 | 41 |

| January 2022 | 32 |

| February 2022 | 35 |

| March 2022 | 38 |

| April 2022 | 54 |

| May 2022 | 35 |

| June 2022 | 7 |

| July 2022 | 12 |

| August 2022 | 23 |

| September 2022 | 67 |

| October 2022 | 37 |

| November 2022 | 36 |

| December 2022 | 63 |

| January 2023 | 33 |

| February 2023 | 42 |

| March 2023 | 19 |

| April 2023 | 47 |

| May 2023 | 22 |

| June 2023 | 14 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| August 2023 | 52 |

| September 2023 | 29 |

| October 2023 | 25 |

| November 2023 | 43 |

| December 2023 | 55 |

| January 2024 | 75 |

| February 2024 | 58 |

| March 2024 | 59 |

| April 2024 | 65 |

| May 2024 | 91 |

| June 2024 | 23 |

| July 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 24 |

| September 2024 | 2 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Editorial Board

- Author Guidelines

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1937-5239

- Print ISSN 0002-8762

- Copyright © 2024 The American Historical Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Africa and Diaspora Studies

- African American Studies

- Arts and Leisure

- Business and Labor

- Education and Academia

- Government and Politics

- Religion and Spirituality

- Science and Medicine

- Agriculture

- Archives, Collections, and Libraries

- Art and Architecture

- Business and Industry

- Exploration, Pioneering, and Native Peoples

- Health and Medicine

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Law and Criminology

- Military and Intelligence Operations

- Miscellaneous Occupations and Realms of Renown

- Performing Arts

- Science and Technology

- Society and Social Change

- Sports and Games

- Writing and Publishing

- Before 1400: The Ancient and Medieval Worlds

- 1400–1774: The Age of Exploration and the Colonial Era

- 1775–1800: The American Revolution and Early Republic

- 1801–1860: The Antebellum Era and Slave Economy

- 1861–1865: The Civil War

- 1866–1876: Reconstruction

- 1877–1928: The Age of Segregation and the Progressive Era

- 1929–1940: The Great Depression and the New Deal

- 1941–1954: WWII and Postwar Desegregation

- 1955–1971: Civil Rights Era

- 1972–present: The Contemporary World

- Download chapter (pdf)

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Black power movement..

- Lloren A. Foster

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.45287

- Published in print: 09 February 2009

- Published online: 01 December 2009

A version of this article originally appeared in The Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present .

In 1849 Frederick Douglass noted in “No Progress without Struggle” that “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Black Power itself was such a demand, a demand from blacks to the white power structure. Considered a twentieth-century phenomenon, philosophically the rhetoric of Black Power actually finds its origins in the “freedom” discourse of the Declaration of Independence and the discourse on the respect for personhood of the U.S. Constitution. Ironically, this same constitution defined blacks as equaling three-fifths of a human being, and voting rights were conferred to the slave owner. Ideologically, Black Power finds its antecedents in the antislavery rhetoric of the early eighteenth century that fought to change the material reality of enslaved and free blacks.

Black Power was expressed culturally in the early writings of African Americans. The critical discourse of Black Power is seen in the abolitionist writings and speeches of David Walker ( Walker's Appeal , 1829 ), Henry Highland Garnet (“Call to Rebellion” speech, 1843 ), Martin Delany ( Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States , 1852 ), James T. Holly ( A Vindication of the Capacity of the Negro Race for Self--Government and Civilized Progress , 1857 ), and Alexander Crummell (“The Relations and Duties of Free Colored Men in America to Africa,” 1860 , and the “Future of Africa,” 1862 ): together they show the germinations of a Pan-African consciousness tied to the ideology of self-reliance and self-determinism. Also, the slave narratives of Harriet Jacobs , Frederick Douglass , and Henry Bibby argued for Black Power in the abolition of slavery.