Become a member of The Marshall Project during our fall member drive. Our journalism has tremendous power to drive change, but we can’t do it without your support.

My Dad Went to Prison When I Was 5. Now I Write About Families Like Mine

Growing up with a father who was incarcerated didn’t define me. but it certainly taught me to challenge stereotypes and ask better questions..

In 1986, in Oakland, California, my father was convicted of second-degree murder. At 29, he began serving 16 years to life in prison. I was 5 years old.

From the moment my tiny beige hand touched the scratched glass partition, my father’s hand covering mine from the other side, the separation was real. Like the millions of kids who would come after me, I leaned my face into the receiver and whispered, “When you coming home?” My brothers, tucked in the booth with me, waited for the answer. “I don’t know baby. As soon as I can.” My eldest brother, as usual, wailed uncontrollably. He was the only one old enough to understand that this separation could be permanent.

In just two years my life had transformed. It seemed like yesterday we were a different kind of family. My mom making biscuits from scratch on Saturday mornings, swaying gently to the sound of the O’Jays on our record player. The heady, sweet aroma of her homemade syrup wafting through our apartment. My father slipping into the kitchen and dipping a fork into the side of the skillet, trying to sneak a bit of bacon. In between all the joy, my mother had bouts of sickness. Labored breathing, coughing and wheezing seemed to be normal parts of her life, my brothers’ too—they all had horrific asthma. The doctors suggested my mom slow down, but she couldn’t. Taking care of us gave her life.

Asthma, a formidable foe, had greedily sucked away her last breath. That same year, following my mother’s death, my father’s life as widower and doting dad meant helping my brothers with their homework, taking us to the doctor, and making dinner on the nights we didn’t devour our favorite Kwik-Way hamburgers. Unbeknownst to us, he also had drug houses dotting the corners of several tattered Oakland blocks. His new lifestyle resulted in him being implicated in a drug-related homicide.

As a child, I got used to the barbed wire gates and the officer holding a rifle in the gun tower. I knew prison guards would make me undo my hair in the hopes of finding heroin tucked in the folds of my braids. It was merely the price I had to pay the prison deities. In exchange for surrendering my freedom, I was allowed to see my father.

I thought then that we were the only kids with a parent in prison. I was wrong. It took decades for me to realize my father, my brothers and I represented sobering statistics. We're among millions of families who've had an immediate family member spend time in prison.

Today, I’m a journalist and I just published my first book, “The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family.” In the book I follow the fears, challenges and small victories of three families—Black and White, poor and middle class—struggling to live within the confines of a brutal system. I uncover a shadow system of laws and regulations that dehumanize the incarcerated , profit off their loved ones and snatch at the seams of the family fabric. This includes mandatory sentencing laws, restrictions on prison visitation and astronomical charges for brief phone calls.

The prevailing question I get is, “Do you write because of your father?” The answer is layered. After losing my mother to asthma and my father to a life sentence in prison before my 6th birthday, my childhood was filled with unanswered questions:

How could my mother die of an asthma attack ? Why did all of my brothers have asthma? Why did a California judge sentence my father to life in prison? What impacted my father’s decisions? Why was he in a prison so far away from home ? Why couldn’t I talk to and see him frequently? Why did my cousins and I pick flowers from neighborhood gardens and sell them to our only White neighbors?

These questions, I believe, led me to study sociology as an undergraduate and pursue graduate training in journalism. I learned the tools to trace how redlining systematically denied Black people access to credit and to home and business loans, which ensured housing segregation for decades to come. I could see how families like mine were relegated to a resource-depleted community shaped by structural racism. I could see how America’s unequal distribution of imprisonment had exacerbated inequality.

My personal experience means that I can cut past the stereotypes and begin with better questions. Once, during an interview about mass incarceration , a radio host asked me if I or my siblings had been locked up. When I confirmed that one of my brothers had served time, she said she had been willing to bet that was the case. Many, the interviewer continued, would argue that my brother visiting my father in prison paved the way for his own incarceration. But my brother and I would have been worse off if we didn’t get to visit my father. Sharing a chocolate bar with my dad in a prison visiting room amounted to the joy of three Christmases, and my brother felt protected sitting on my dad’s lap. This host thought of intergenerational incarceration as something you catch like a common cold, not something orchestrated and sustained by structural inequality, biased legislation and racial disparities in sentencing.

My experience as a child of an incarcerated father also widens the lens in which I witness the world. I think of the time in Jackson, Mississippi, when I met a doe-eyed, chestnut hued, 8-year-old named Xacey. She wore a T-shirt with prisoners’ faces on it—her father’s included—and quickly told me she was “fighting for civil rights” and for her uncles and father to get out of prison. In that moment, surrounded by support, she was bold and loved her father fearlessly, but she kept this truth a secret in school.

So, I write for girls and boys like her, brave in one moment and afraid and ashamed the next. I write because the effects of parental incarceration are dogged. This is larger than me.

My father served nearly 27 years in prison. In 2012, I helped secure a lawyer for the parole hearing that resulted in him coming home. I’ve been lucky to have him on this journey with me. Whenever I hit a rough patch writing “The Shadow System,” he was a free phone call away. My father was a steady voice of reason, a compassionate ear, and someone who could quell the rage when it felt like it would spill out of my chest. He could hop on a flight and meet me in Miami to connect with my brother. Now, when I’m doing virtual book events, you can catch my dad in the chat box being my biggest champion.

Sylvia A. Harvey reports at the intersection of race, class, policy and incarceration. She is the author of “The Shadow System: Mass Incarceration and the American Family.” You can connect with her on social media as @Ms_SAH.

Our reporting has real impact on the criminal justice system

Our journalism establishes facts, exposes failures and examines solutions for a criminal justice system in crisis. If you believe in what we do, become a member today.

Stay up to date on our reporting and analysis.

"My Father's Passing"

University of Michigan

2. The lessons we take from obstacles we encounter can be fundamental to later success. Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. How did it affect you, and what did you learn from the experience?

250 - 650 words

Why This Essay Works:

- Navigates Tragedy Gracefully : Writing about a tragedy like a loss of a parent is a tricky topic for college essays. Many students feel obligated to choose that topic if it applies to them, but it can be challenging to not come across as trying to garner sympathy ("sob story"). This student does a graceful job of focusing on positive elements from their father's legacy, particularly the inspiration they draw from him.

- Compelling Motivations : This student does a great job of connecting their educational and career aspirations to their background. Admissions officers want to understand why you're pursing what you are, and by explaining the origin of your interests, you can have compelling and genuine reasons why.

What They Might Change:

- Write Only From Your Perspective : In this essay, the student writes from their hypothetical perspective as an infant. This doesn't quite work because they likely wouldn't remember these moments ("I have no conscious memories of him"), but still writes as though they do. By writing about things you haven't seen or experienced yourself, it can come across as "made up" or inauthentic.

© 2018- 2024 Essays That Worked . All rights reserved.

Registration on or use of this site constitutes acceptance of our Terms and Conditions , Privacy Policy , and Cookie Policy .

We have no affiliation with any university or colleges on this site. All product names, logos, and brands are the property of their respective owners.

An official website of the United States government, Department of Justice.

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Hidden Consequences: The Impact of Incarceration on Dependent Children

Family members of incarcerated individuals are often referred to as "hidden victims" — victims of the criminal justice system who are neither acknowledged nor given a platform to be heard. These hidden victims receive little personal support and do not benefit from the systemic societal mechanisms generally available to direct crime victims, despite their prevalence and their similarities to direct crime victims. [1]

Children whose parents are involved in the criminal justice system, in particular, face a host of challenges and difficulties: psychological strain, antisocial behavior, suspension or expulsion from school, economic hardship, and criminal activity. It is difficult to predict how a child will fare when a parent is intermittently or continually incarcerated, and research findings on these children's risk factors are mixed.

However, research suggests that the strength or weakness of the parent-child bond and the quality of the child and family's social support system play significant roles in the child's ability to overcome challenges and succeed in life. [2] Therefore, it is critical that correctional practitioners develop strong partnerships with law enforcement, public schools, and child welfare agencies to understand the unique dynamics of the family in question and try to ensure a safety net for the child and successful re-entry for the incarcerated parent.

This article summarizes the range of risk factors facing children of incarcerated parents. It also cautions against universal policy solutions that seek to address these risk factors but do not take into account the child's unique needs, the child's relationship with the incarcerated parent, and alternative support systems.

Scope of the Problem

The massive increase in incarceration in the United States has been well publicized. In the 1970s, there were around 340,000 Americans incarcerated; today, there are approximately 2.3 million. [3] One consequence of this dramatic increase is that more mothers and fathers with dependent children are in prison. Since the war on drugs began in the 1980s, for example, the rate of children with incarcerated mothers has increased 100 percent, and the rate of those with incarcerated fathers has increased more than 75 percent. [4]

Current estimates of the number of children with incarcerated parents vary. One report found that the number of children who have experienced parental incarceration at least once in their childhood may range from 1.7 million to 2.7 million. [5] If this estimate is on target, that means 11 percent of all children may be at risk. [6] The rate of parenthood among those incarcerated is roughly the same as the rate in the general population: 50 percent to 75 percent of incarcerated individuals report having a minor child. [7]

Relying as we often do on a few statistics to describe a national phenomenon, we can easily be misled to believe that all segments of the population equally share the burden of parental incarceration. A closer examination of the numbers, however, reveals that communities of color are more at risk: Data from 2007 (the most recent data available) show that African-American children and Hispanic children were 7.5 times more likely and 2.3 times more likely, respectively, than white children to have an incarcerated parent. [8] Also, 40 percent of all incarcerated parents were African-American fathers. [9] The burden of parental incarceration on these communities has changed over time. For example, about 15 percent of African-American children born in the 1970s had a parent who was incarcerated. Twenty years later, the rate had nearly doubled to 28 percent. [10]

Unfortunately, parental incarceration is only one of a series of separations and stressful situations facing children whose parent is involved in the criminal justice system. If we consider the full continuum of the criminal justice process — arrest, pre-trial detention, conviction, jail, probation, imprisonment, and parole — the number of children affected is significantly larger. For example, if we include parents who have been arrested, the estimate of affected children rises to 10 million. [11] Although research to date has focused more on children with incarcerated parents than on children with parents in other phases of the system, the two groups may share many of the same risk factors and needs. Policymakers and practitioners must understand these characteristics to develop effective systemic responses.

Parental Incarceration and Child Risk Factors

Although each case is unique and each child responds differently, research has established that a parent's incarceration poses several threats to a child's emotional, physical, educational, and financial well-being.

Child criminal involvement

There is particular concern that a parent's imprisonment will lead to a cycle of intergenerational criminal behavior. But risk factors rarely present themselves across all children, and these behaviors are difficult to understand or predict. One study, for example, found that children of incarcerated mothers had much higher rates of incarceration — and even earlier and more frequent arrests — than children of incarcerated fathers. [12] Although we need more research on this relationship, this differential may speak to the likelihood that the mother, on average, is a primary support for the child. [13]

Psychological problems and antisocial behavior

Research on depression and aggression among children of incarcerated parents has been mixed and highly differentiated by gender, age, race, and family situation. One study, for example, found that African-American children and children who have both a mother and a father incarcerated exhibited significant increases in depression. [14]

Another study found that, for the most part, parental incarceration was not associated with a change in childhood aggression — but the findings were decidedly mixed. Twenty percent of sampled children did see an increase in aggression; boys who tended to be aggressive before a parent's incarceration were most at risk for a trajectory of increased aggression. Interestingly, there were some decreases in aggression: About 8 percent of the children saw a return to a stable home upon parental incarceration if their father had lived in the home prior to incarceration and had drug and alcohol issues. [15]

Regardless of the reason, if we as scientists choose which studies to believe and which to ignore on the basis of personal preconceptions rather than scientific merit, how much easier will it be for practitioners to do the same, leading them to reject future scientific advances in psychology and criminal justice?

The most common consequence of parental incarceration appears to fall under the umbrella of antisocial behavior, which describes any number of behaviors that go against social norms, including criminal acts and persistent dishonesty. [16] One meta-analysis of 40 studies on children of incarcerated parents found that antisocial behaviors were present more consistently than any other factors, including mental health issues and drug use. [17] A separate study built on those findings by examining the presence of multiple adverse childhood experiences a child may face, including incarceration. The study found that exposure to multiple adverse childhood experiences throughout development may put children at risk for severe depression and other issues that persist into adulthood, including substance abuse, sexually transmitted diseases, and suicide attempts. [18] Antisocial behavior resulting from parental incarceration may limit a child's resilience in the face of other negative experiences, which could then compound the effects of exposure to other issues.

Educational attainment

Research has frequently found an association between children's low educational attainment and parental incarceration. But once again, the findings to date are confounding and indicate that more research needs to be done to provide a clear picture of this dynamic.

For example, one study found that parental incarceration was strongly associated with externalizing behavioral problems. The researcher failed to see a corresponding decrease in educational outcomes and other social attainment factors but assumed this was due to the limited follow-up window of data. Interestingly, the researcher did acknowledge that some children were able to develop resilience and deal with their externalizing behavior problems before suffering negative educational outcomes. [19] But a separate study found that children of incarcerated parents are significantly more likely to be suspended and expelled from school. [20] More research needs to be conducted to isolate the impact of parental incarceration on educational attainment from that of other risk factors.

Economic well-being

The overwhelming majority of children with incarcerated parents have restricted economic resources available for their support. One study found that the family's income was 22 percent lower during the incarceration period and 15 percent lower after the parent's re-entry. [21] (Note that this reduction of income and earning potential does not describe how limited the earning potential may have been before incarceration.) But here too, the impact can be nuanced: Another study found that a mother's incarceration was associated with greater economic detriment, especially if the father did not live with the family. This economic loss might be exacerbated if the child lives with a caregiver who is already responsible for other dependents or with a grandparent who lives on retirement income. [22] A third study found that children of incarcerated parents systemically faced a host of disadvantages, such as monetary hardship; were less likely to live in a two-parent home; and were less likely to have stable housing. [23]

Parent-child attachment and contact while incarcerated

If the parent is a strong support in the child's life, the interruption of the child-parent relationship will lead to or exacerbate many of the issues or risk factors already discussed. [24] Conversely, in some cases a child might benefit from the removal of a parent who presented problems for the child. [25] Any attempt to facilitate contact between the incarcerated parent and child should consider the quality of the relationship the child had with the parent before incarceration. Visits while the parent is in the facility seem to do little to build a relationship if there was not one prior to incarceration.

Research shows that visits by family and loved ones reduce recidivism among incarcerated individuals [26] and that strong family support is one of the biggest factors in a successful re-entry experience. [27] But when it comes to a child's visits, the results are once again mixed. One study reviewed the literature and found that when the parent and child have a positive relationship, visits encourage attachment and promote a positive relationship after release. When the parent and child had no relationship prior to incarceration, however, visits do not seem to be enough to promote a positive relationship. [28]

NIJ-funded research examined the impact visits have on the child. Researchers found that when the child had a prior positive relationship with the parent, the child tended to benefit psychologically from a visit. But when there was no prior relationship with the parent, the child actually exhibited many of the externalizing behaviors discussed above, as reported by their caregivers. A positive parent-child relationship had to exist before incarceration for the incarcerated parent and child to benefit from the visit. [29]

More research is needed to tease out when, for whom, and in what circumstances parent-child visitation should be encouraged. Although the quality of the pre-incarceration parent-child relationship is critical, further research may show that visits may be beneficial — or detrimental — at certain ages and stages of childhood development. Also, particular factors surrounding the parental incarceration, such as whether the child witnessed the parent's arrest, could worsen the impact. [30] The effect of parental incarceration on a child is complex and may be hard to predict, except that there is risk that the child will be substantially and negatively affected.

Policy Implications

Many children of incarcerated parents face profound adversity — as do other children facing many of the same risk factors the children experienced prior to parental incarceration. But the research shows that some children develop resilience despite the risks if they have a strong social support system. [31] Through visits, letter writing, and other forms of contact, an incarcerated parent can play an important positive role in a child's sphere of support. In some circumstances, however, continued contact may have little value and even be detrimental to the child. Continued research will help policymakers and corrections practitioners better understand these complex and competing issues and make critical policy and program decisions to help children have positive life outcomes and avoid the criminal justice system.

Correctional facilities

The research shows that, in general, children whose parents are incarcerated are at higher risk for increased antisocial behaviors and psychological problems, such as depression. Whether this translates into decreased educational attainment, involvement with the criminal justice system, and other negative outcomes seems to depend on the child's resilience and his or her social support network.

The biggest predictor is the strength of the parent-child relationship. For example, if the parent lived with the child, provided social and financial support, and developed a strong parent-child bond, the long-term negative effects of parental incarceration may be mitigated if the child receives support throughout the incarceration period and is afforded opportunities to maintain contact with the parent. Correctional facilities can support the relationship by providing the child with easy access to and visitation with the parent in a child-friendly environment.

Making policy recommendations is particularly difficult, however, in cases where the parent's presence was not supportive or productive for the child or where the parent was not present at all. For example, a program evaluation of a video message service showed that a correctional facility parenting class had little impact on the quality of the parents' messages; the children largely responded to the messages based on the relationship before incarceration. [32] Thus, the prior parent-child relationship seems to be critical in determining the impact of contact from the parent. This limits the degree to which correctional officials can positively intervene to promote a relationship between a parent and a child.

Given this, correctional practitioners need to understand the relationship between the incarcerated parent and child prior to incarceration, to the extent possible, since contact between the two will likely benefit or harm one or both of them depending on the quality of their initial relationship.

Other service providers

Although a correctional facility's capacity to improve relationships and assist with the child's welfare may be limited, other service providers and partners may be able to intervene. For example, if schools were notified of the parent's arrest or incarceration, then they could address negative behaviors before they result in negative outcomes. Furthermore, as one researcher pointed out, many law enforcement agencies do not have protocols for handling a child present at an arrest. [33]

Law enforcement and child welfare practitioners are often involved with the child before the correctional system is involved with the parent, so enhanced and streamlined communication between the various government entities could maximize the potential to provide the child whatever support is available. For example, NIJ-funded research on crossover youth cited the "one family, one judge" model, which combines cases in child welfare and juvenile justice to provide a streamlined and consistent approach to services for the child and family. [34] If law enforcement, child welfare, educational, and correctional practitioners can share information on the child and family experiencing parental incarceration, then it would be more likely that the child would benefit from early intervention if he or she appears to be at risk for sustained deprivation, loss of educational attainment, or criminal activity. Such a partnership would also benefit correctional practitioners and re-entry managers, who would have better information on the child's situation and prior relationship with the incarcerated parent, which seems to be critical for the child's welfare.

Given these considerations, it appears that enhancing communication between corrections practitioners and other service providers is a good way to ensure a safety net for the child and facilitate a successful re-entry for the incarcerated parent.

For More Information

Read an NIJ Journal article, "Does Parental Incarceration Increase a Child's Risk for Foster Care Placement?"

About This Article

This artice appeared in NIJ Journal Issue 278 , May 2017.

[note 1] Myrna Raeder, "Making a Better World for Children of Incarcerated Parents," Family Court Review 50 no. 1 (2012): 23-35.

[note 2] Rebecca Shlafer, Erica Gerrity, Ebony Ruhland, and Marc Wheeler, Children With Incarcerated Parents — Considering Children's Outcomes in the Context of Family Experiences (St. Paul, MN: University of Minnesota, 2013).

[note 3] Ibid.

[note 4] Ibid.

[note 5] Ibid.

[note 6] Jean M. Kjellstrand and J. Mark Eddy, "Parental Incarceration During Childhood, Family Context, and Youth Problem Behavior Across Adolescence," Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 50 no. 1 (2011): 18-36.

[note 7] Susan Roxburgh and Chivon Fitch, "Parental Status, Child Contact, and Well-Being Among Incarcerated Men and Women," Journal of Family Issues 35 no. 10 (2014): 1394-1412; Christopher Mumola, Incarcerated Parents and Their Children (pdf, 12 pages) , Special Report, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, August 2000, NCJ 182335.

[note 8] Lauren Glaze and Laura Maruschak, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children (pdf, 25 pages) , Special Report, Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, August 2008, NCJ 222984; Holly Foster and John Hagen, "The Mass Incarceration of Parents in America: Issues of Race/Ethnicity, Collateral Damage to Children, and Prisoner Reentry," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 623 (2009): 179-194.

[note 9] PEW Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs: Incarceration's Effect on Economic Mobility (Washington, DC: PEW Charitable Trusts, 2010).

[note 10] Albert Kopak and Dorothy Smith-Ruiz, "Criminal Justice Involvement, Drug Use, and Depression Among African American Children of Incarcerated Parents," Race and Justice 6 no. 2 (2016): 89-116.

[note 11] Raeder, "Making a Better World for Children of Incarcerated Parents," 23-35.

[note 12] Kopak and Smith-Ruiz, "Criminal Justice Involvement, Drug Use, and Depression Among African American Children of Incarcerated Parents," 89-116.

[note 13] Glaze and Maruschak, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children, 5.

[note 14] Kopak and Smith-Ruiz, "Criminal Justice Involvement, Drug Use, and Depression Among African American Children of Incarcerated Parents," 89-116.

[note 15] William Dyer, Investigating the Various Ways Parental Incarceration Affects Children: An Application of Mixture Regression (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, 2009).

[note 16] Joseph Murray, David Farrington, and Ivana Sekol, "Children's Antisocial Behavior, Mental Health, Drug Use, and Educational Performance After Parental Incarceration: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis," Psychological Bulletin 138 no. 2 (2012): 175-210.

[note 17] Ibid.

[note 18] Shlafer et al., Children With Incarcerated Parents, 5.

[note 19] Megan Cox, The Relationships Between Episodes of Parental Incarceration and Students' Psycho-Social and Educational Outcomes: An Analysis of Risk Factors (Philadelphia: Temple University, 2009).

[note 20] PEW Charitable Trusts, Collateral Costs.

[note 21] Ibid.

[note 22] Keva Miller, "The Impact of Parental Incarceration on Children: An Emerging Need for Effective Interventions," Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 23 no. 4 (2006): 472-486.

[note 23] Amanda Geller, Irwin Garfinkel, Carey Cooper, and Ronald Mincy, "Parental Incarceration and Child Well-Being: Implications for Urban Families," Social Science Quarterly 90 no. 5 (2009): 1186-1202.

[note 24] Jude Cassidy, Julie Poehlmann, and Phillip Shaver, "An Attachment Perspective on Incarcerated Parents and Their Children," Attachment and Human Development 12 no. 4 (2010): 285-288.

[note 25] Dyer, Investigating the Various Ways Parental Incarceration Affects Children.

[note 26] Joshua Cochran, "The Ties that Bind or Break: Examining the Relationship between Visitation and Prisoner Misconduct," Journal of Criminal Justice 40 (2012): 433-448.

[note 27] Christy Visher and Shannon Courtney, One Year Out: Experiences of Prisoners Returning to Cleveland (Washington, DC: The Urban Institute, 2007).

[note 28] Johanna Folk, Emily Nichols, Danielle Dallaire, and Ann Loper, "Evaluating the Content and Reception of Messages From Incarcerated Parents to Their Children," American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82 no. 4 (2012): 529-541.

[note 29] Melinda Tasca, "'It's Not All Cupcakes and Lollipops': An Investigation of Predictors and Effects of Prison Visitation for Children During Maternal and Parental Incarceration" (pdf, 172 pages) , Final report to the National Institute of Justice, grant number 2013-IJ-CX-0011, February 2014, NCJ 248650.

[note 30] Shlafer et al., Children With Incarcerated Parents.

[note 31] Ibid., 7.

[note 32] Folk et al., "Evaluating the Content and Reception of Messages From Incarcerated Parents to Their Children," 529-541.

[note 33] Raeder, "Making a Better World for Children of Incarcerated Parents," 23-35.

[note 34] Douglas Young, Alex Bowley, Jeanne Bilannin, and Amy Ho, "Traversing Two Systems: An Assessment of Crossover Youth in Maryland" (pdf, 154 pages) , Final report to the National Institute of Justice, grant number 2010-JB-FX-0006, August 2014, NCJ 248679.

About the author

Eric Martin is a social science analyst in NIJ's Office of Research and Evaluation.

Cite this Article

Read more about:.

The statement "One statistic indicates that children of incarcerated parents are, on average, six times more likely to become incarcerated themselves" has been removed from this article. This statistic is seen widely throughout the literature, but the original study resulting in this statistic cannot be found and therefore cannot be treated as fact.

Related Publications

- NIJ Journal Issue No. 278 NIJ Journal,

Parents’ Incarceration Takes Toll on Children, Studies Say

- Share article

Without ever breaking a school rule or getting a low grade, 2.7 million American students are already further along the pipeline to prison than their classmates—simply because they have a parent who is behind bars.

Studies show parental incarceration can be more traumatic to students than even a parent’s death or divorce, and the damage it can cause to students’ education, health, and social relationships puts them at higher risk of one day going to prison themselves. Yet in many schools, that circumstance is a hidden problem, hard for teachers to track and difficult for students and caregivers to discuss.

“Most kids feel it has to be kept a secret,” Amy Friedman, a founder and the executive director of Pain of the Prison System, or POPS, a support club at Venice High School in Los Angeles. “If you have to keep a secret all the time, it makes everything else in school a lot harder.”

At the 2,300-student Venice High, one cramped classroom fills with as many as 60 students on the first Wednesday of each month. The new ones may say nothing, or claim they’re just there for the lunch. The real reason comes out after a few meetings, says Ms. Friedman: All of these students, like Ms. Friedman herself, have fathers, mothers, brothers, or cousins in and out of prison.

More than 2.7 million American children and youths have at least one parent in federal or state prison (with more having parents and other family members in local jails), and one-third of them will reach age 18 while a parent is behind bars, according to the National Resource Center on Children and Families of the Incarcerated, at Rutgers University in Camden, N.J.

There are strong racial disparities: Forty-five percent of children of incarcerated parents are black, compared with 28 percent who are white and 21 percent who are Hispanic.

Long-Term Damage

In the 2014 book Children of the Prison Boom: Mass Incarceration and the Future of American Inequality , researchers Sara Wakefield of Rutgers University-Newark and Christopher Wildeman of Yale University found that one-quarter of black children born in 1990 had a parent in jail or prison by the time the child was age 14—more than double the rate for black children born in 1978.

“Mass incarceration is so unequally distributed across the population, that if incarceration does have an effect on kids’ educational outcomes, it has a disproportionate effect on poor and minority kids, who are already at a disadvantage,” said Kristin Turney, an assistant sociology professor at the University of California, Irvine.

Parental incarceration can be safer for a child, particularly when the parent was imprisoned for domestic violence or child abuse. But regardless of why a parent is behind bars, emerging research suggests it puts children at high and often invisible risk, as well as aggravating existing racial and poverty gaps.

Children of incarcerated parents have higher rates of attention deficits than those with parents missing because of death or divorce, and higher rates of behavioral problems, speech and language delays, and other developmental delays, according to a study published last summer in the Journal of Health and Social Behavior that analyzed data from a national survey of children’s health. In separate but related studies, Ms. Turney also found higher rates of asthma, obesity, depression, and anxiety.

For education, the statistics are equally dramatic: Only 1 percent to 2 percent of students with incarcerated mothers and 13 percent to 25 percent of students with imprisoned fathers graduate from college, according to a 2013 report from the American Bar Association and the White House.

Moreover, having a significant proportion of students with incarcerated parents in a school is associated with lower grade point averages and rates of college graduation, even for classmates without incarcerated parents.

There’s been far less research on the effects of having incarcerated family members beyond parents, but some recent studies suggest siblings of those jailed also struggle with grief, stress , and stigmatization by those who know their sibling is imprisoned.

Searching for Reasons

It is so clear a risk factor that having a member of the household go to prison was considered one of the key “adverse childhood experiences” that California studies found contribute to significant health, educational, and social problems for children even decades later.

“What is it about incarceration that really matters, that is so damaging to kids? We don’t know,” said Ms. Turney, a 2014 scholar for the Foundation for Child Development, for which she is studying the long-term effects of having a father in prison.

“Is it the economic hit that these families take?—with divorce, the father can at least still contribute economically—or is it the stigma and shame for kids?” she said.

In a study published in October in the journal Sociology of Education , Ms. Turney found the elementary-grade children of incarcerated parents were at higher risk of being held back at the end of the year —but not because of significantly lower test scores or more behavior problems than classmates.

Rather, “it was their teachers’ perceptions of the students’ academic proficiency and how well the kid was doing,” Ms. Turney said. “It does suggest that teachers are really important here, and they really play an important role in students’ lives.”

Ms. Friedman, of the POPS club at Venice High, raised her ex-husband’s two daughters while he was in prison. She agreed that stress and shame can make the loss of a parent to incarceration more traumatic.

“The things that come up the most with a parent inside is this feeling that you are going to be just like them,” Ms. Friedman said, “and there’s this fear and loss and disappointment that translates to depression in a lot of kids.”

Building Supports

POPS and the U.S. Dream Academy—an eight-city, after-school program supporting children and families of incarcerated people—are among a growing group of programs dedicated to buffering the academic and emotional effects of having a family member in prison.

Evroy Marrett is the director of the Washington branch of the Dream Academy, located at the Learning Center at Turner Elementary School, said the after-school program tries not only to replace the homework help and reading support a missing parent might provide, but also the more nebulous “dream building” and opinion formulation that develop with parents’ help.

“When it’s not directly linked to say, nutrition, a big part of [the damage of parental incarceration] is not having that guidance in the home,” Mr. Marrett said. “It’s just involvement, period.”

The Dream Academy also provides support to the student’s caregiver—often a mother, grandmother or aunt, Mr. Marrett said.

“A lot of times, you’ll see a shift in behavior, and a lot of times you may not know what it is,” Mr. Marrett said. “As we talk to moms or aunts, the picture starts to come clear, that the father has been arrested or had a parole hearing.”

For students who go into foster care, helping parents stay involved in their education can make a big difference in whether those children continue relationships with their incarcerated parents at all.

Under the federal Adoption and Safe Families Act, or ASFA, a child-welfare agency will seek to end parental rights if a child has been in foster care for 15 of the past 22 months—including when the parent is behind bars. However, 32 states allow exceptions if there is a “compelling reason to believe that terminating the parent’s rights is not in the best interests of the child"—including if a parent has made meaningful attempts to stay connected to the child.

That’s not an easy task for a parent in prison. More than 40 percent of those in federal prison are kept at least 500 miles from home, and 61 percent of those in state prison are incarcerated 100 or more miles away, according to a presentation by Philip M. Genty, a clinical professor of professional responsibility at Columbia Law School, which he gave as part of a 2013 White House symposium on children of incarcerated parents.

“They can’t go to parent-teacher nights; they can’t be there to help with homework; they have very little access to the children.” Ms. Friedman said.

Among the limited programs intended to keep incarcerated parents connected to their children, those focused on schooling are rarest. In the early 2000s, Florida offered some mothers in prison opportunities to read to their children regularly through videoconferences, but the program did not continue.

“There are a lot of programs for the incarcerated, but not so many for the collateral damage out here,” Ms. Friedman said.

A version of this article appeared in the February 25, 2015 edition of Education Week as Children of Inmates Seen at Risk

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Create a free Diverse: Issues In Higher Education account to continue reading

Scholarships Open Door to College for Children of Incarcerated Parents

When Alijah Nelson began to search for local scholarships, an organization that awards scholarships exclusively for children of incarcerated parents caught his attention.

“ There’s a lot of crazy scholarships for crazy things,” Nelson recalled. “And this was just so unique to me and my situation,” he said of the scholarships being offered from the Ava’s Grace Scholarship Foundation, a scholarship organization started in 2010 on behalf of children of incarcerated parents in the St. Louis region.

Nelson —who wrote an essay about how his parents landed in prison after dealing drugs out of the family’s St. Louis apartment as part of his scholarship application —is one of eight students to win a scholarship from Ava’s Grace.

The scholarships are from $3,000 to $5,000 and are renewable for four years. This is the first year that 75 percent of the scholarships from Ava ’s Grace were awarded to young Black males . That decision stems in part from a large donation made to Ava’s Grace in the wake of 18-year-old Michael Brown ’s shooting death last year at the hands of a Ferguson, Missouri, police officer that sparked nationwide protests over police brutality and the use of excessive force against young Black men.

Nelson plans to use his scholarship to attend Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota, this fall. He said the Ava ’ s Grace scholarship is important to him “mainly because I’m a first generation student and it helps me overcome the financial barrier of higher education that can scare most people away.”

“It ’ s a meaningful scholarship because my parents ’ incarceration time was a turning pivotal point in my life,” Nelson said. “Also to be rewarded for overcoming such a barrier means a lot.”

Ava ’s Grace is one of a small number of organizations that provides scholarships for children of incarcerated parents.

Experts say there is a need for more such efforts to be made on behalf of the nearly three million children in the United States with a parent in jail or prison on any given day.

“ They deserve special attention because they face many significant barriers in their lives,” said Bryce Peterson, a research associate at the Urban Institute ’ s Justice Policy Center. “Compared to other kids, they are also more likely to face economic strain, experience housing instability, be at risk of a variety of behavioral and emotional problems, and fail or drop out of school.”

Nelson wrote about such instability after his parents began to sell drugs out of their third-floor apartment in St. Louis. Previously, Nelson wrote, his father worked at a fast food restaurant and his mother was a hairstylist.

The utilities were often shut off, he said, but the lights stayed on after his parents started serving clients of a different sort.

“ Random strangers would pound on the door, waking us up on school nights,” Nelson wrote. “Curious, I asked my parents what was going on.

“ They simply told me the truth when they could have easily sugarcoated the situation,” his essay continued. “My parents had become drug dealers.”

Nelson went on to describe the fallout that ensued when his father became incarcerated —how Nelson and his two older brothers and younger sister had to go live with their grandmother due to the fact that they were living in an unsafe environment.

He spoke of the anxiety that he experienced when he would visit his father in prison.

“ Not knowing the system at the time, I thought we were going to go pick him up and bring him back home with us,” Nelson wrote. “When the guard came to get him to be placed back in the facility, I felt that feeling of being separated again.”

Despite having an incarcerated parent, Nelson fostered his love for science, which began when he was a little kid who resorted to an unconventional way to disassemble his toys so he could see how they worked.

“ My parents couldn ’ t afford tools, so instead I would drop the toys from the third floor window and gravity would do the rest,” Nelson wrote. “My parents tried to collect the pieces for me to throw them away, but I stored them in a shoe box instead, saving my experimentation for later.”

Ava ’s Grace was launched in 2010 by St. Louis resident Stephanie Regagnon, whose mother was imprisoned when she was a young adult.

There is at least one other organization that awards scholarships to children of incarcerated parents. It is called Creative Corrections Education Fund, and it was launched in 2012 by Percy Pitzer, a former federal prison warden, and his wife, Sununt.

Similar to Ava ’s Grace, a major focus of Creative Corrections Education Fund is to “break the cycle” of incarceration.

“ It’s just that these particular kids have a much greater chance of being incarcerated themselves than probably anybody else,” Pitzer said. “They follow in their parents’ footsteps.”

Pitzer ’s organization has awarded 92 scholarships for $1,000 a piece since its inception.

“ That helps them, believe it or not,” Pitzer said. “When you don’t have anything, a thousand dollars is a lot.”

Indeed, various research and surveys have found that some students were prevented from continuing from one semester to the next by as little as $500.

Nelson —who first heard about Ava’s Grace while participating in the academic enrichment program at College Bound St. Louis —likely won’t have that problem. His $5,000 renewable scholarship is worth ten times that amount.

Nelson said he decided to go to college out of state on the advice of relatives who encouraged him to “go past St . Louis and see something different.”

He also didn ’t want to fall into the same trap of his older brothers.

“ My older siblings who went to local colleges would come back home and never go back (to college),” Nelson said. “So they really played a huge role in my decision to go out of state.”

Nelson said both of his parents are back home, working and “staying out of trouble.” He said other young people who are experiencing childhoods similar to his should stay hopeful despite the odds.

“ To those growing up in the same circumstances as me I would say go seek opportunity and don’t be afraid to ask for help,” Nelson said. “Don’t fall victim to your situation and dig yourself into a ditch.

“ Dream big and be bigger than your situation,” Nelson said. “Your decision to change and do better will inspire so many around you.”

Jamaal Abdul-Alim can be reached at [email protected] . Or you can follow him on Twitter @dcwriter360 .

Report: Black Girls Receive More Frequent and More Severe Discipline in School Than Other Girls

![college essay about parent in jail Su Jin Jez [124930]](https://img.diverseeducation.com/files/base/diverse/all/image/2024/09/Su_Jin_Jez__124930_.66ef2d51183b3.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&rect=0%2C1255%2C6583%2C3703&w=100)

Addressing How Student Parents Are Underserved

Brown Experiences Decline in Rates of Incoming Black, Brown Students

Survey Shows Impacts of Law Student Debt

Common App Launches 2024-25 Direct Admissions Program

Proposed Legislation Would Create Program to Support Students’ Basic Needs

Fostering Success

Executive Director, Mays Cancer Center

Tenured/tenure-track: open rank, assistant professor, health and health education, director of military center connections, human resources clerk (confidential), assistant professor of biology - vertebrate biologist.

- Josephine Hallam

- Meet the Team

- Our Results

- Scholarship

- Child Abuse

- Domestic Violence

- Motor Vehicle Theft

- Sexual Abuse

- Testimonials

Free Consultation (602) 237-5373 Se habla Español

Experienced, powerful advocate and trial attorney on your side

Hallam law group scholarship for children of incarcerated parents.

Hallam Law Group is happy to announce that we are offering a scholarship aimed at passionate students of incarcerated parents looking to further their education.

Having a parent (or both parents) in jail or prison can take a serious toll on a child’s social behavior and mental health. It can also have a significant impact on that child’s educational prospects. The social stigma, emotional trauma and financial hardships that typically come with an incarcerated parent all play a role in that negative impact. At Hallam Law Group, we created this scholarship to help students offset that hardship and allow them to focus on their education.

Scholarship Requirements

All applicants must meet the following criteria:

• You must be a junior or senior in high school, or a freshman in a community college or 4-year university (no trade schools). • You must have at least one parent who has been incarcerated by the Department of Corrections.

How to Apply

To apply, please use the form below to submit an essay explaining how having an incarcerated parents has affected you, your parents, and other members of your family.

There is no word count requirement, but we encourage you to write as much as it takes to effectively convey your current situation. Do not hesitate to tell us more about your background, and how your circumstances may have influenced your goals for the future.

Scholarship Amount

We will select the best entrant to receive $1,000 for any education-related expenses, such as tuition and textbooks.

Summer August 31st, 2024

- First Name * First

- Last Name * Last

- Address * Street Address Address Line 2

- Select State Select State Alabama Alaska Arizona Arkansas California Colorado Connecticut Delaware District of Columbia Florida Georgia Hawaii Idaho Illinois Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Louisiana Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nebraska Nevada New Hampshire New Jersey New Mexico New York North Carolina North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Oregon Pennsylvania Rhode Island South Carolina South Dakota Tennessee Texas Utah Vermont Virginia Washington West Virginia Wisconsin Wyoming Armed Forces Americas Armed Forces Europe Armed Forces Pacific State

- ZIP Code ZIP Code

- Phone Number *

- Scholarship Essay * Accepted file types: pdf, doc, docx, Max. file size: 8 MB.

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Contact Us Today

For a free consultation.

- Name * First

- Name * Last

- All fields are required

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

3838 North Central Avenue Suite 1800 Phoenix, Arizona 85012

Hallam Law Group © 2024. All rights reserved. Disclaimer

College Essay: My Parents’ Sacrifice Makes Me Strong

After living in Texas briefly, my mom moved in with my aunt in Minnesota, where she helped raise my cousins while my aunt and uncle worked. My mom still glances to the building where she first lived. I think it’s amazing how she first moved here, she lived in a small apartment and now owns a house.

My dad’s family was poor. He dropped out of elementary school to work. My dad was the only son my grandpa had. My dad thought he was responsible to help his family out, so he decided to leave for Minnesota because of many work opportunities .

My parents met working in cleaning at the IDS C enter during night shifts. I am their only child, and their main priority was not leaving me alone while they worked. My mom left her cleaning job to work mornings at a warehouse. My dad continued his job in cleaning at night.

My dad would get me ready for school and walked me to the bus stop while waiting in the cold. When I arrived home from school, my dad had dinner prepared and the house cleaned. I would eat with him at the table while watching TV, but he left after to pick up my mom from work.

My mom would get home in the afternoon. Most memories of my mom are watching her lying down on the couch watching her n ovelas – S panish soap operas – a nd falling asleep in the living room. I knew her job was physically tiring, so I didn’t bother her.

Seeing my parents work hard and challenge Mexican customs influence my values today as a person. As a child, my dad cooked and cleaned, to help out my mom, which is rare in Mexican culture. Conservative Mexicans believe men are superior to women; women are seen as housewives who cook, clean and obey their husbands. My parents constantly tell me I should get an education to never depend on a man. My family challenged machismo , Mexican sexism, by creating their own values and future.

My parents encouraged me to, “ ponte las pilas ” in school, which translates to “put on your batteries” in English. It means that I should put in effort and work into achieving my goal. I was taught that school is the key object in life. I stay up late to complete all my homework assignments, because of this I miss a good amount of sleep, but I’m willing to put in effort to have good grades that will benefit me. I have softball practice right after school, so I try to do nearly all of my homework ahead of time, so I won’t end up behind.

My parents taught me to set high standards for myself. My school operates on a 4.0-scale. During lunch, my friends talked joyfully about earning a 3.25 on a test. When I earn less than a 4.25, I feel disappointed. My friends reacted with, “You should be happy. You’re extra . ” Hearing that phrase flashbacks to my parents seeing my grades. My mom would pressure me to do better when I don’t earn all 4.0s

Every once in awhile , I struggled with following their value of education. It can be difficult to balance school, sports and life. My parents think I’m too young to complain about life. They don’t think I’m tired, because I don’t physically work, but don’t understand that I’m mentally tired and stressed out. It’s hard for them to understand this because they didn’t have the experience of going to school.

The way I could thank my parents for their sacrifice is accomplishing their American dream by going to college and graduating to have a professional career. I visualize the day I graduate college with my degree, so my family celebrates by having a carne asada (BBQ) in the yard. All my friends, relatives, and family friends would be there to congratulate me on my accomplishments.

As teenagers, my parents worked hard manual labor jobs to be able to provide for themselves and their family. Both of them woke up early in the morning to head to work. Staying up late to earn extra cash. As teenagers, my parents tried going to school here in the U.S . but weren’t able to, so they continued to work. Early in the morning now, my dad arrives home from work at 2:30 a.m ., wakes up to drop me off at school around 7:30 a.m . , so I can focus on studying hard to earn good grades. My parents want me to stay in school and not prefer work to head on their same path as them. Their struggle influences me to have a good work ethic in school and go against the odds.

© 2024 ThreeSixty Journalism • Login

ThreeSixty Journalism,

a nonprofit program of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of St. Thomas, uses the principles of strong writing and reporting to help diverse Minnesota youth tell the stories of their lives and communities.

June 17, 2021

Less poverty, less prison, more college: what two parents mean for black and white children.

- Children are significantly more likely to avoid poverty and prison, and to graduate from college, if they are raised in an intact two-parent family. Tweet This

- From poverty to college graduation to incarceration, black children and young adults from two-parent families are more likely to be flourishing than their white peers from single-parent families. Tweet This

- On average, black young adults from families headed by their mother and father are more likely to be flourishing educationally than black young adults from non-intact homes. Tweet This

“Children who grow up in a household with only one biological parent are worse off, on average, than children who grow up in a household with both of their biological parents, regardless of the parents’ race or educational background.” ~ Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur, Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps

Princeton University sociology professor Sara McClanahan summarized the social scientific consensus about the importance of family structure for children with her colleague Gary Sandefur in this passage from their magisterial 1992 book, Growing Up with A Single Parent . In recent years, many other scholars have come to similar conclusions, from Paul Amato at Penn State to Isabel Sawhill at the Brookings Institution to Melanie Wasserman at UCLA. The consensus view has been that children are more likely to flourish in an intact, two-parent family, compared to children in single-parent or stepfamilies.

But this consensus view is now being challenged by a new generation of scholarship and scholars. For instance, sociologist Christina Cross at Harvard University recently published an op-ed in The New York Times entitled, “The Myth of the Two-Parent Home,” that contended “living apart from a biological parent does not carry the same cost for black youths as for their white peers.” In The Times and in another op-ed this month in The Harvard Gazette , she draws on her work indicating that black children are less affected by family structure on a number of educational outcomes to make the argument that family structure is less consequential for black children. In recent years, other family scholars ( here and here ) have also called into question the idea that children do better in stable two-parent families.

One practical implication of this revisionist line of research is that children may not benefit from having their father in the household. Another implication is that the value of the two-parent family may be markedly different across racial lines, with black children less likely to benefit from such a family. Accordingly, in this Institute for Families Studies research brief, we investigate two questions:

1) Are black children more likely to flourish in an intact, two-parent home compared to black children raised by single-parents or in stepfamilies? We focus on these three subgroups because they are the largest family groups for American children today, including African American children. And we answer this question by looking at three important outcomes: child poverty, college graduation, and incarceration.

2) Is the association between family structure and child outcomes markedly different by race? Here, we focus on comparing white and black children in intact, two-parent families to their peers in non-intact families—single-parent families, stepfamilies, and other families. Our aim is to determine if the association is different for black children compared to white children on the three outcomes noted above.

Family Structure and Black Child Outcomes

Today, 37% of black children are living in a home headed by their own two biological parents, 48% are living in a home headed by a single parent, and 4% are living in a stepfamily with one biological parent and one non-biological parent, according to the March 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS). 1 In this research brief, we explore how these three family structures are associated with child poverty, college graduation, and incarceration. We draw on data from the American Community Survey (ACS) 2015-2019 Five Year Estimates 2 and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1997 cohort). Specifically, NLSY97 follows the lives of a national representative sample of American youth born between 1980 and 1984. The survey started in 1997 when the youth were ages 12 to 17. We used the wave that was surveyed in 2013/2014, when the cohort was at least 28 years old.

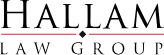

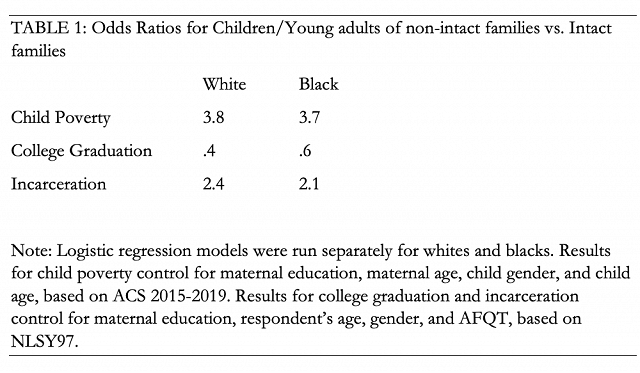

Figure 1 indicates that black children in homes headed by single parents are about 3.5 times more likely to be living in poverty compared to black children living with two parents in a first marriage, our measure of intact families in the ACS. 3 Those in likely step-families are approximately 2.5 times more likely to be poor. 4 Moreover, after controlling for maternal education, age, children’s age and gender, we find that the odds of being poor for black children in non-intact families are 3.7 times higher than for black children in intact, married families. 5 Clearly, black children in stable, married families are better off financially.

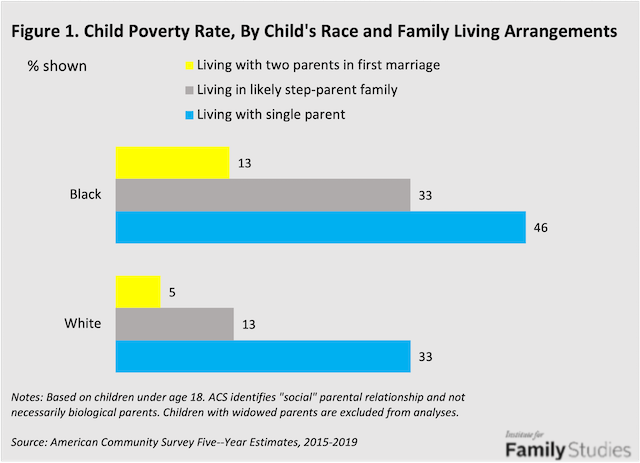

Figure 2 shows that college graduation is markedly more common among black young adults raised by their two biological parents, our measure of intact families in the NLSY97. 6 Specifically, data from the NLSY97 indicate young adults from intact families are almost twice as likely to graduate from college than their peers who grew up with single parents, and approximately 1.5 times more likely to have a college degree compared to peers in stepfamilies. After controlling for maternal education, as well as young adults’ gender, age, and AFQT scores, we find the odds of black young adults getting a college degree are almost 70% higher if they were raised by their own two parents. Clearly, on average, black young adults from families headed by their mother and father are more likely to be flourishing educationally than black young adults from non-intact homes. 7

There is also a clear connection between family structure and incarceration for black young adults. Black young adults who grew up in a single-parent home are about 1.8 times more likely to have spent time in prison or jail by their late twenties, compared to their peers from a home headed by two biological parents. Those from stepfamilies are also more likely to have been incarcerated. In a multivariate context with the same controls noted above, young black adults in non-intact homes have about two times the odds of having ever been incarcerated compared to their peers in intact homes.

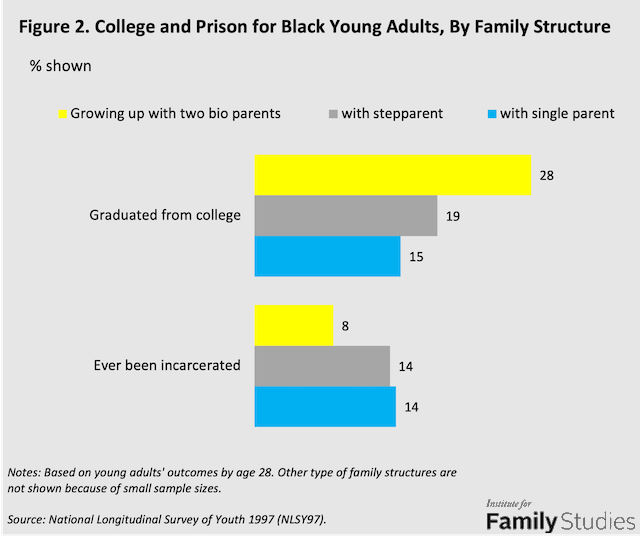

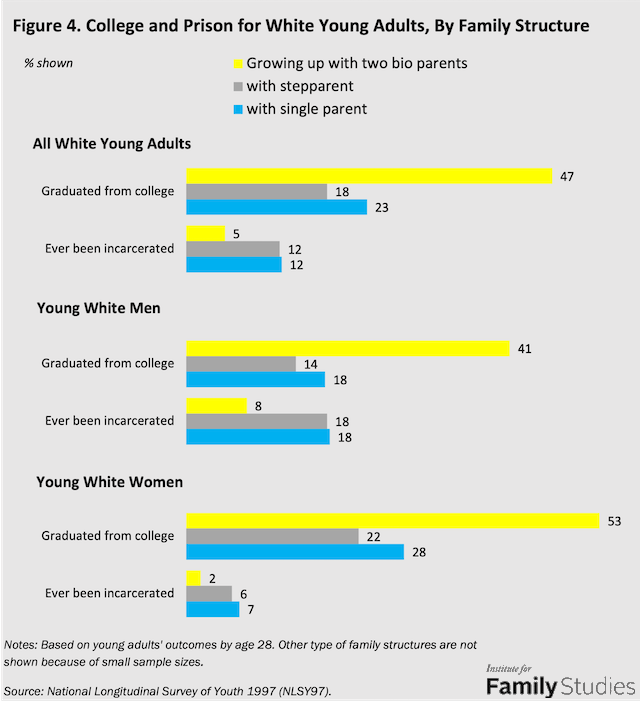

Because patterns in college completion and incarceration vary by gender, we also explore the link between family structure and these two outcomes separately for young black men and women. Figure 3 indicates that young black men from an intact, two-parent family are much more likely to graduate from college than their peers raised by single parents and stepfamilies, and their incarceration rate is also much lower (14% vs. 24% for single parents and 26% for stepfamilies). A similar pattern applies to young black women as well. More than one-third of young black women (36%) from intact families have had a college degree by their late twenties; the share among black women raised by single parents is 18% and among stepfamilies is 25%.

Black-White Comparison

Clearly, there are differences in poverty, college graduation, and incarceration by family structure among African Americans. But are these differences similar or different to the ones for whites? Note that 67% of white children today are in homes headed by their biological parents, 21% of white children are in homes headed by a single parent, and 6% are living with a biological parent and stepparent, according to the March 2020 Current Population Survey.

The first noteworthy finding in comparing patterns across race, gender, and family structure is that black children from intact families do uniformly better than white children from single-parent households. From poverty to college graduation to incarceration, black children and young adults from two-parent families are more likely to be flourishing than their white peers from single-parent families. For instance, 36% of young black women from intact families have graduated from college compared to just 28% of young white women from single-parent families. Likewise, 14% of young black men from intact families have been incarcerated, compared to 18% of young white men from single-parent families. Moreover, 13% of black children in intact families are poor compared to 33% of white children in single-parent families.

At the same time, it is important to note that the figures also show that whites are more advantaged within each family structure category. For instance, only 28% of black young adults from intact families have graduated from college compared to 47% of white young adults from intact families. This is a large difference and is but one example of the fact that a stable two-parent family is not a panacea when it comes to addressing racial inequalities in America. The nation’s legacy of racial discrimination, unequal access to a quality education, concentrated poverty, and ongoing experiences with racial prejudice are among the structural factors that help explain the racial differences in outcomes this brief finds between blacks and whites who have the same family structure.

The third noteworthy finding here is that the family structure association for black and white children is similar when it comes to poverty and prison. Net of controls, being in non-intact homes more than triples both black and white children’s odds of being in poverty. As young adults, those growing up from nonintact families are twice as likely to have been incarcerated compared to those from intact families, regardless of race. For both black and white children, growing up in a home with your two parents seems to reduce your risk of poverty and prison in about the same way.

But, consistent with Cross’ research, the link between family structure and college completion is clearly weaker for blacks than for whites. Net of controls, growing up in a non-intact family reduces the odds of college graduation by 60% for white young adults, but only by 40% for black young adults. Nevertheless, both black and white young adults from non-intact families are still at a disadvantage relative to their peers who grew up with both parents. In other words, it is also clear that black young adults from intact families are markedly more likely to graduate from college than their black peers in non-intact families—and white peers from non-intact families.

In Conclusion

Using new Census data and the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, this brief finds that black and white children from intact homes are significantly more likely to be flourishing economically, educationally, and socially on the three outcomes examined here: child poverty, education, and incarceration.

At the same time, consistent with Cross’ research, we do find that the association between family structure and one major education outcome, college graduation, is weaker for black children than white children. Nevertheless, young black adults are significantly more likely to graduate from college if they grew up in an intact family.

Our results also indicate that a stable, two-parent family is no panacea for African-American children. Black children in stable, two-parent families are more likely to experience poverty and incarceration, and less likely to graduate from college, compared to their white peers from stable, two-parent families. Racial inequality casts a shadow even on black children in intact families.

To be clear, this descriptive brief does not make claims about causality. A number of factors not measured in this brief may confound the associations between family structure and child outcomes documented here. Young adults’ family structure growing up is obviously endogenous to their family income, for instance, given that married parents tend to have a higher income than single parents. Here, progressives tend to minimize the ways that family income is a consequence of family structure (two parents can more easily earn a decent income than one parent) even as conservatives tend to minimize the ways that a stable marriage is a consequence of a decent income (relationships are stronger when they are undergirded by a steady income).

What we can conclude is, consistent with a longstanding social scientific consensus about family structure, children are significantly more likely to avoid poverty and prison, and to graduate from college, if they are raised in an intact two-parent family. This association remains true for both black and white children. In the vast majority of cases, these homes are headed by their own married mother and father.

In sum, it is no “myth” to point out that boys and girls are more likely to flourish today in America if they are raised in a stable, two-parent home. It is simply the truth that white and black children usually do better when raised by their own mother and father, compared to single-parent and stepfamilies. Our results, then, also suggest the fraying fabric of American family life, where more kids grow up apart from one of their two parents—usually their own father—is an “equal opportunity tsunami,” posing obstacles to the healthy development of children from all backgrounds.

Brad Wilcox is professor of sociology and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies, and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies. Ian Rowe is a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and the CEO of Vertex Partnership Academies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Samuel McIntyre, Joseph P. Price, Peyton W. Roth, Scott Winship, Jared Wright, and Nicholas Zill for their input and assistance. Any errors are our own.

1. Courtesy of Nicholas Zill, the analysis is based on March 2020 Current Population Survey (CPS). The vast majority of black children in two biological parent families are in families headed by married parents; only a small fraction are in cohabiting families. See: https://ifstudies.org/blog/1-in-2-a-new-estimate-of-the-share-of-children-being-raised-by-married-parents .

2. Authors’ analysis of American Community Survey (ACS) 2015–2019 five-year estimates. Data were accessed at Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Sophia Foster, Ronald Goeken, Jose Pacas, Megan Schouweiler and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 11.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V11.0

3. This includes intact, same-sex families and intact, adoptive families. However, the vast majority of children in intact, married families in the ACS are in intact, heterosexual families. See, for instance, https://ifstudies.org/blog/a-portrait-of-contemporary-family-living-arrangements-for-us-children .

4. For poverty estimates, households were identified as likely “step-parent” families if the parents were married and either parent reported they had been married more than once. Families headed by a single widowed parent were excluded from the analyses. Data were accessed at Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Sophia Foster, Ronald Goeken, Jose Pacas, Megan Schouweiler and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 11.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V11.0 .

5. The comparison group is children in single-parent, stepfamilies, and other families not headed by an intact married couple.

6. The vast majority of these families are headed by married biological parents but also include a small number of cohabiting biological parents. See: https://ifstudies.org/blog/1-in-2-a-new-estimate-of-the-share-of-children-being-raised-by-married-parents .

7. The comparison group here is children from single parent, stepfamilies, and other families not headed by two biological parents.

Related Posts

How dads affect their daughters into adulthood, baby bust: fertility is declining the most among minority women, what three identical strangers reveals about nature and nurture, five facts about today’s single fathers, fewer american high schoolers having sex than ever before, family breakdown and america’s welfare system, join the ifs mailing list.

Sign up for our mailing list to receive ongoing updates from IFS.

© 2024 Institute for Family Studies

- Our Mission

- Books & Articles

- Get Married

- Success Sequence

- Public Education

Interested in learning more about the work of the Institute for Family Studies? Please feel free to contact us by using your preferred method detailed below.

Mailing Address:

P.O. Box 1502 Charlottesville, VA 22902

(434) 260-1048

Media Inquiries

For media inquiries, contact Chris Bullivant ( [email protected] ).

We encourage members of the media interested in learning more about the people and projects behind the work of the Institute for Family Studies to get started by perusing our "Media Kit" materials.

- [email protected]

- (650) 338-8226

Cupertino, CA

- Our Philosophy

- Our Results

- News, Media, and Press

- Common Application

- College Application Essay Editing

- Extracurricular Planning

- Academic Guidance

- Summer Programs

- Interview Preparation

Middle School

- Pre-High School Consultation

- Boarding School Admissions

College Admissions

- Academic and Extracurricular Profile Evaluation

- Senior Editor College Application Program

- Summer Program Applications

- Private Consulting Program

- Transfer Admissions

- UC Transfer Admissions

- Ivy League Transfer Admissions

Graduate Admissions

- Graduate School Admissions

- MBA Admissions

Private Tutoring

- SAT/ACT Tutoring

- AP Exam Tutoring

- Olympiad Training

Academic Programs

- Passion Project Program

- Science Research Program

- Humanities Competitions

- Ad Hoc Consulting

- Athletic Recruitment

- National Universities Rankings

- Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings

- Public Schools Rankings

Acceptance Rates

- University Acceptance Rates

- Transfer Acceptance Rates

- Supplemental Essays

- College Admissions Data

- Chances Calculator

- GPA Calculator

National Universities

- College Acceptance Rates

- College Overall Acceptance Rates

- College Regular Acceptance Rates

- College Early Acceptance Rates

- Ivy League Acceptance Rates

- Ivy League Overall Acceptance Rates

- Ivy League Regular Acceptance Rates

- Ivy League Early Acceptance Rates

Public Schools

- Public Schools Acceptance Rates

- Public Schools Overall Acceptance Rates

- Public Schools Regular Acceptance Rates

- Public Schools Early Acceptance Rates

Liberal Arts

- Liberal Arts Colleges Acceptance Rates

- Liberal Arts Colleges Overall Acceptance Rates

- Liberal Arts Colleges Regular Acceptance Rates

- Liberal Arts Colleges Early Acceptance Rates

5 Ways to Make College Essays About Tragedy More Memorable

By Eric Eng

Difficult and personal topics of tragedy and loss aren’t easy for many people to talk about, let alone write about for others to read. This makes college essays about tragedy challenging for many applicants.

To be sure, a college essay on the death of a parent or death in a family can have a positive impact on a student’s application. The gravity of these subjects makes them impactful, full of emotions, and very captivating for admissions officers. However, a college essay about losing a loved one will only work if they’re done right. Since so many students experience tragedy and loss at some point in their lives, these topics can come across as generic.

Writing About Tragedy in the College Application Essay: Should It Be Done?

When preparing to write a meaningful, personal, and impactful college application essay, something tragic that’s happened in your life might seem like a fitting topic. It’s revealing, emotional, and raw. Well, you’ll hear a variety of different opinions when you ask whether or not painful college essays are a good idea.

Critics of sad college essays say that these subjects can come across as generic since many applicants struggle with similar experiences or issues. Tragedy is a universal phenomenon that humans experience, after all. However, another group will say that these stories are so personal and important that you’re doing yourself a disservice by not writing about them. Sad college essays are a great way to share a life struggle and what you learned from it.

So, what’s the real answer? Should you write a college essay about death or any tragedies? At AdmissionSight , we’ve helped hundreds of students write their winning college application essays, and this is a common topic that we’re asked about. Through our experience, we can confidently say that tragedy and loss are appropriate subjects for your college essay if – and only if – they’re approached carefully and with a clear sense of purpose.