- Our Mission

Simple Ways to Promote Student Voice in the Classroom

Giving students some say over what happens in class can promote engagement and a strong sense of community.

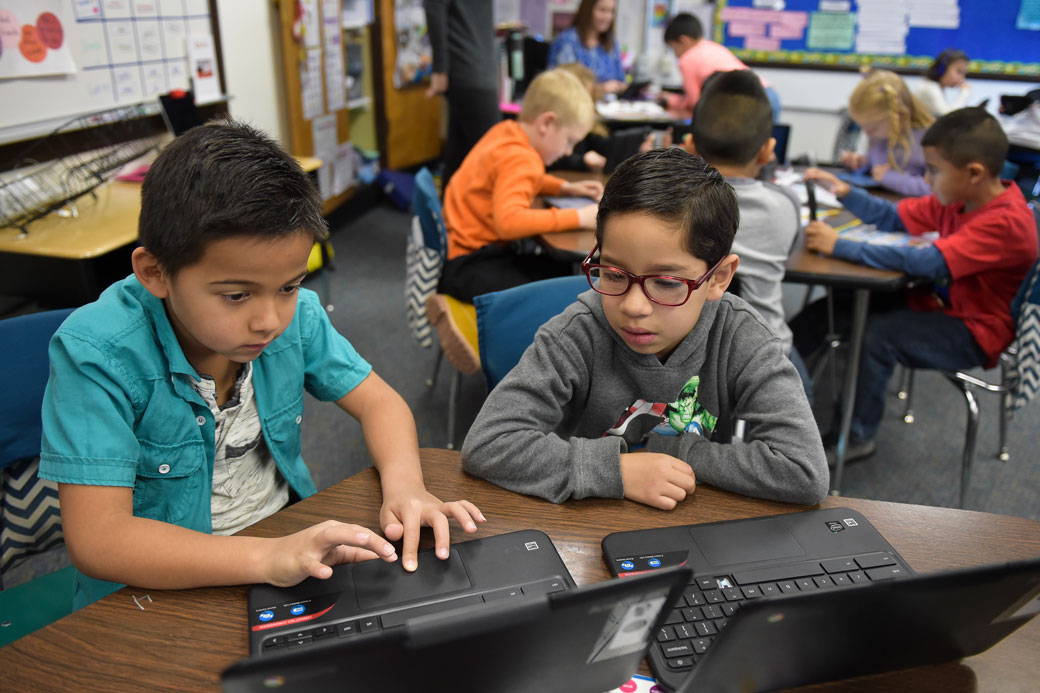

One of the most powerful ways to impact achievement is to actively engage students in the life of the classroom. Although educators know that our students’ contributions are vital to the learning process, educator and author Alexis Wiggins was surprised to observe that many students “feel like a bit of a nuisance all day long.” As teachers, we have the capacity to change our students’ experiences if we design lessons that prioritize student voice and participation.

Elevating student voice is critical for many reasons. For one thing, as Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey write , “The amount of talk that students do is correlated with their achievement.” There are strategies teachers can use to elevate student voice in order to strengthen relationships, foster a sense of belonging, increase engagement, and inform instruction.

Begin Class With a Welcoming Ritual

Students arrive to class with their minds swirling about failed quizzes, mounting pressure about homework assignments, and concerns about interactions with their peers. In order to help them clear these distractions from their minds, we might begin class with a predictable routine.

Students might share “breaking news” or “what’s on the top of your mind?” in pairs, with small groups, or with the whole class. This welcoming ritual allows students to release their most pressing thoughts and create space for new experiences. It also builds relationships between students as they share a little bit of themselves with their peers. Welcoming rituals foster a sense of belonging as the classroom becomes a place that accepts students not only for who they are but where they are at a particular moment.

This brief share might transition directly into an opening activity that connects to the learning of the day. Together, students might consider an essential question, share responses to a short quote or passage, or take time to reflect on the previous day’s learning. Opening class with an emphasis on student engagement rather than passive compliance prioritizes student voice and places students at the center of the learning experience.

Plan Consistent Opportunities for Student Voice

During the planning stage, prioritize active engagement and student voice by asking yourself:

- When will students collaborate to problem-solve, devise higher-order questions , contribute to the creation of a product, or otherwise actively grapple with a lesson’s meaning?

- How often are students offered the opportunity to speak at the front of the room, write on the board, or conduct demonstrations on the document camera?

- When are students writing for an audience beyond the classroom?

- Do students have choices regarding the work they’re doing?

- If (and in what ways) are students prompted to connect what they’re learning in the classroom to their lives outside of school?

Ideally, our classrooms would be places where students not only gain knowledge but also discover who they are and who they want to be. The only way students will come to these realizations is through both independent and collaborative explorations in which they add their voices to the conversation. Prioritizing student voice strengthens a sense of belonging, as the learning experiences are co-created by students and teachers.

Ask Students About Their Lives Beyond The Classroom

We need to show our students that we value who they are and understand the complexities of their lives. Some students will clearly make themselves known while others will fade into the background if we let them—so we need to intentionally interact with all students. These moments of listening and sharing with students reinforce belonging and build relationships.

We can do this while greeting students when they enter the classroom, while conferring with small groups, and while conferencing with individual students. We can schedule “lunch and learn” sessions or invite students to help us hang student work or otherwise contribute to the logistics of the classroom during their study halls or lunch periods.

When students know we value what they have to say, they’re more likely to share their thoughts and insights. It may seem like we don’t have time to engage with every student, but we don’t have time not to. As John Hattie reminds us , “A positive, caring, respectful climate in the classroom is a prior condition to learning.” Strong teacher-student relationships bolster students’ confidence to share their voices.

Ask for Student Feedback—and Use It

Another important way to elevate student voice is to ask for feedback. As much as we wish we could, we will never know what it really feels like to be a student in our classrooms, and our students hold many of the answers we seek. We can ask them for feedback throughout the year and (when feasible) implement their suggestions. Student feedback not only informs instruction, it conveys that we value their insight, and that their voices are at the center of the work that we do.

When we listen to and honor our students, we can show them that their voices can be powerful instruments of learning for themselves and others—and levers of change in their classrooms and beyond.

Center for American Progress

Elevating Student Voice in Education

- Report PDF (1 MB)

This report outlines strategies to increase authentic student voice in education at the school, district, and state levels.

Advancing Racial Equity and Justice, Education, Education, K-12, Racial Equity and Community-Informed Policies +1 More

Media Contact

Mishka espey.

Senior Manager, Media Relations

[email protected]

Government Affairs

Madeline shepherd.

Senior Director, Government Affairs

In this article

Introduction and summary

Students have the greatest stake in their education but little to no say in how it is delivered. This lack of agency represents a lost opportunity to accelerate learning and prepare students for a world in which taking initiative and learning new skills are increasingly paramount to success.

InProgress Stay informed on the most pressing issues of our time.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

When it comes to student engagement, there is a predictable and well-documented downward trajectory as students get older. According to a 2016 Gallup poll that measured student engagement, about three-quarters of fifth graders—an age at which students are full of joy and enthusiasm for school—report high engagement in school. 1 By middle school, slightly more than one-half of students report being engaged. 2 In high school, however, there is a precipitous drop in engagement, with just about one-third of students reporting being engaged. 3 Similar to the drop in engagement, a recent poll from The New Teacher Project (TNTP) found that students see less value in their work and assignments with each subsequent year of school. 4

There are limited studies that show a direct connection between student engagement and students valuing their education and opportunities to make their voices heard. Many advocates and researchers encourage schools to create opportunities for students to participate in decisions about their education as a means of increasing student engagement and investing students in their education. 5

The authors of this report define “student voice” as student input in their education ranging from input into the instructional topics, the way students learn, the way schools are designed, and more. Increasing student voice is particularly important for historically marginalized populations, including students from Black, Latinx, Native American, and low-income communities as well as students with disabilities.

Given the assumption that student voice can increase student engagement, such efforts to give students more ownership of their education may be linked to improvements in student outcomes. 6 For example, a 2006 Civic Enterprises report, which surveyed a diverse group of 16- to 24-year-old adults who did not graduate high school, found that 47 percent of respondents indicated that “classes were not interesting” as the main reason they dropped out. 7 Sixty-nine percent of participants said that they were not motivated to work hard. 8 Interestingly, the percentage of students who did not feel inspired to work hard increased among students with lower GPAs; among high-, medium-, and low-GPA students, 56 percent, 74 percent, and 79 percent reported not feeling inspired to work hard, respectively. Surveyed students and focus groups emphasized the need for student voice in curricula development, improved instruction practices, and increased graduation rates. 9

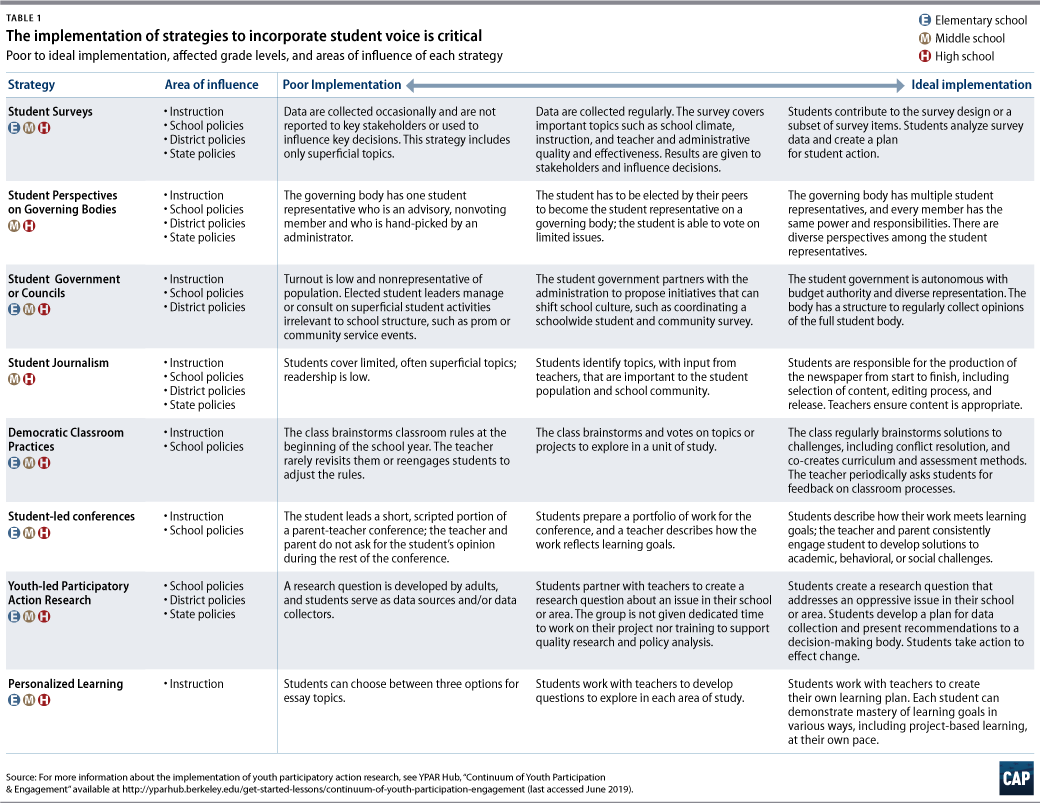

States, districts, schools, and teachers can solicit and incorporate student voice in many ways. Some of these strategies fundamentally change the way that schools and systems operate, and others are more marginal. This report provides an overview of eight approaches that teachers, school leaders, and district and state policymakers can use to incorporate student voice: student surveys; student perspectives on governing bodies such as school, local, state decision-makers; student government; student journalism; student-led conferences; democratic classroom practices; personalized learning; and youth participatory action research (YPAR).

Implementation of these strategies matters greatly. Efforts to incorporate student voice are stronger when they include the following elements: intentional efforts to incorporate multiple student voices, especially those that have been historically marginalized; a strong vision from educational leaders; clarity of purpose and areas of influence; time and structures for student-adult communication; and, most importantly, trust between students and educators. 10 Policymakers and educators should also incorporate principles of universal design to ensure that these efforts are accessible to all students and recognize the voices of all students, including students with disabilities and students whose first language is not English.

This report concludes with policy recommendations for school, district, and state policymakers.

Youth activism has been in the spotlight of late due to several high-profile efforts, including the advocacy of youth who oppose the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival program as well as the Parkland, Florida, students who galvanized around meaningful gun control. 11 Youth have also crafted public opposition letters to education officials to protest policies that perpetuate the school-to-prison pipeline and its disproportionate criminalization of Black and Latinx students, LGBTQ students, and students with disabilities. 12 For instance, a group of youth activists called the Voices of Youth in Chicago Education were instrumental in driving the narrative and advocating for statewide change that resulted in the 2015 passage of SB 100 in Illinois, which addressed harsh, punitive discipline policies in school. 13

This youth activism is remarkable and helps change the debate on key issues facing the United States. This report, however, focuses on incorporating student voice within existing educational institutions.

What is student voice?

The authors of this report define student voice as authentic student input or leadership in instruction, school structures, or education policies that can promote meaningful change in education systems, practice, and/or policy by empowering students as change agents, often working in partnership with adult educators. 14

Expert definitions of student voice

“At the simplest level, student voice can consist of young people sharing their opinions of school problems with administrators and facility. Student voice initiatives can also be more extensive, for instance, when young people collaborate with adults to address the problems in their schools—and in rare cases when youth assume leadership roles to change efforts.” 15

–Dana Mitra, a Pennsylvania State University scholar on education policy and student voice

“[A] broad term describing a range of activities that can occur in and out of school. It can be understood as expression, performance, and creativity and as co-constructing the teaching/learning dynamic. It can also be understood as self-determined goal-setting or simply as agency.” 16

–Eric Toshalis, senior director of impact at KnowledgeWorks who focuses on student engagement and motivation

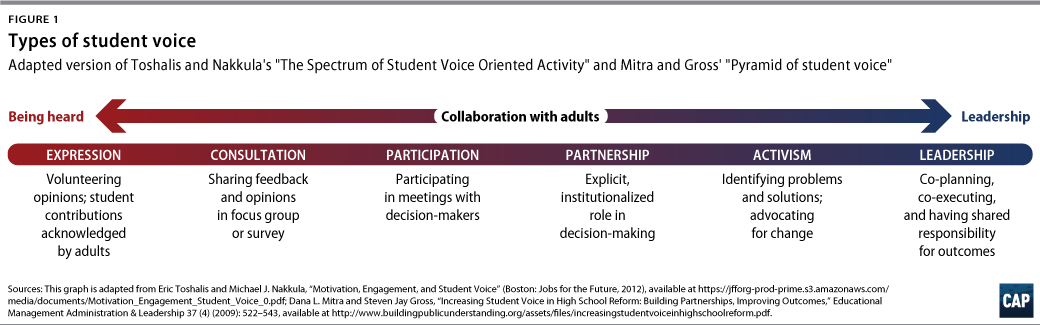

Experts on student voice, including Mitra and Toshalis, describe student voice as a spectrum or pyramid to illustrate that different forms of student engagement foster different levels of agency. 17 On the one hand, adults gather and use student perspectives, feedback, and opinions to inform change. On the other hand, students participate in decision-making bodies that drive change. 18 Student agency increases as students assume more leadership and have greater responsibility and accountability in instruction or policy changes.

All forms of student voice can be important and can meaningfully influence instruction, schools, and policies. But each approach has trade-offs, and one may be more appropriate to achieve certain goals than others. For example, schoolwide or districtwide surveys provide a snapshot in time with answers to a limited number of largely multiple-choice questions and often measure changes in the views of a large group of students over time. Student leadership through governing bodies or YPAR can allow for meaningful and extended conversations about complex topics and implementation; in most instances, however, this approach engages fewer students.

Strategies to incorporate student voice

Teachers, schools, and policymakers can use different strategies to incorporate student perspectives and empower students to lead. These strategies engage students at different points on the student voice spectrum and are not mutually exclusive. Schools and policymakers can adopt one or many of these strategies, as appropriate, to engage students and ensure that schools reflect the interests and needs of the populations they serve.

This section lists the most common student voice strategies based on CAP research; the pros and cons of each approach and suggestions for how to maximize the strategy’s effect; and one or more short descriptions of the strategies in practice. Student surveys are the first focus in this section because they can be a useful tool at all levels of education decision-making—state, district, school, and classroom. Next, the authors list strategies in the order of scale of reach, starting with those that can influence state policies and ending with those that affect individual learning. As discussed later in the report, implementation is critical to ensure that each strategy supports authentic student voice. 19

Student surveys

Surveys efficiently collect many student perspectives. The content and purpose of student surveys vary. Districts, schools, or teachers may choose to design and administer surveys to collect baseline information on student interests, school climate, rigor or quality of instruction, student behaviors, and perception of their own power to establish goals and measure growth over time.

Some surveys are formative, meaning they are designed to shed light on strengths, weaknesses, and areas on which to focus improvement but not to inform high-stakes evaluations. Other surveys are designed to assess certain programs, classrooms, or schools. Formative tools, for example, are classroom surveys that give private feedback to a teacher. Other surveys may have higher stakes. For instance, a district may opt to use student surveys as a factor in school ratings or as a component of teacher evaluations. Some student surveys are administered statewide, and the summary results are made available to the public. For instance, the Illinois Youth Survey is administered to students in grades eight, 10, and 12 and includes questions about drug use, experiences with violence, attitudes and engagement in school, and mental and physical health. 20 Other places such as the CORE Districts in California use student climate surveys in their accountability systems. 21

The level to which student surveys influence policies and the student experience depends on the purpose and design of the survey and how the results are used. Policymakers should use valid and reliable survey tools in high-stakes evaluations as a component of a school accountability framework. And while some survey data can provide meaningful, formative results, data can, in some instances, be unreliable due to reference bias—the effect of survey respondents’ reference points on their answers, among other concerns. 22 For example, there is growing interest in collecting information about social and emotional learning, but survey data unfairly hurt high-performing schools. 23 That is because, in general, students in higher-performing schools with more rigorous expectations rate themselves lower in self-control and work ethic than students in lower-performing schools. Researchers have developed valid survey tools to measure school culture and climate. 24

The design, topics addressed, and intended use of the survey will also influence the need to protect students’ privacy and the confidentiality of survey information. Educators need to be mindful of federal privacy laws, specifically the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment and the Family and Educational Rights and Privacy Act, when developing surveys.

- Collects information from the entire target student population rather than a subset

- Provides a fair process for ascertaining student opinions in a way that students do not influence one another

- Can be designed, administered, and scored easily and at a relatively low cost

- Can be used to set goals and measure growth over time

- Can disaggregate data to determine if there are variations among racial and ethnic groups, students from families with low incomes, or students from other identity groups

- Can be used to compare schools when administered statewide or districtwide and can provide additional information and context beyond test scores to understand school quality

- Represents only a snapshot in time

- May not allow for nuanced responses from students

- May not get at core aspects of student experience in the school

- Risks being ineffectual if survey data are not acted upon

- Does not empower students to lead the change they desire

- Leaves open the possibility that teachers or administrators will seek to influence results to be seen in a more favorable light, particularly when consequences are attached to the results

How to maximize the strategy

- Use as part of a broader strategy to empower students as change agents

- Administer surveys with students as creators or even co-researchers who analyze data and provide recommendations to improve school climate and practices

- Be thoughtful around the use of survey results as an accountability measure for school quality, if at all

- Maximize response rates and find ways to increase investment among students and parents and be consistent in recruitment efforts

- Ensure that surveys are universally designed and accessible to all students through translation for students who are learning English, accommodations for students with disabilities, and access to necessary technology

Student surveys inform school ratings in New York City Public Schools

Since 2007, the New York City Public School District has conducted an annual survey that targets parents, teachers, and students in grades six through 12. The results are included in each school’s rating, and principals are encouraged to use the data to improve instruction, culture, professional development, and family engagement strategies. The student survey is anonymous and includes questions to examine academic rigor and supportive environment. 25 Over the past decade, about 80 percent of students in participating grades took the survey. 26

Empowering students to analyze and develop solutions using survey data

Unleashing the Power of Partnership for Learning (UP for Learning) is a Vermont-based nonprofit organization that fosters student voice through a youth-adult partnership model. The organization helps students not only share their perspective, but also analyze data, develop data-informed solutions, and become agents of change. 27 The organization partners with schools to prepare students to advocate for change based on Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) data, a survey administered nationally by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention every two years to collect data on health behaviors and high school students’ experiences. 28 In response to limited follow-up opportunities for students to be able to analyze the data, UP for Learning piloted the Getting to Y initiative in Vermont high schools and has implemented the initiative for about 10 years since. Schools reach out to UP for Learning to train students in data analysis and facilitation. Students use these skills to bring meaning to YRBS data, develop recommended policy or programmatic changes, and implement these changes accordingly. UP for Learning worked with the University of New Mexico at Albuquerque to replicate the model. 29

Student perspectives on governing bodies

Decision-making bodies at the school, district, and state levels can give students an active role or consider student perspectives. This approach can take different forms: Policymakers can allow students to serve on decision-making bodies such as state or district school boards or in a voting or advisory capacity on school committees; form a group of students to serve on a parallel, student-only body akin to a student school board; or create student advisory committees—similar to the way that many states and districts convene teacher advisory committees—to weigh in on important policy debates. 30

Including students or their perspectives in governing bodies actively engages students in the education system and provides a point of view that is often underrepresented. 31 As consumers and beneficiaries of the education system, students have a different perspective than teachers, administrators, and parents—and that unique insight can shed light on new approaches or solutions. 32 Engaging student perspectives generates important feedback and creates a sense of ownership that can lead to higher student performance. 33

For school-level governing bodies, partnering with students can help develop culturally sustaining educational practices and select curricula and instructional materials that are most relevant and engaging to their various communities. While teachers should be proactive in incorporating culturally responsive instruction, students can help highlight practices and instructional materials that align to student interests and values to help educators avoid blind spots. 34

Various districts and states include students on their boards of education. A 2014 analysis of student participation on state boards of education (SBOE) by SoundOut, a nonprofit organization that partners with educators, districts, and district officials to implement student voice initiatives, found that 19 states included at least one student member on their SBOE. 35 For example, the Pennsylvania SBOE changed its bylaws in 2008 to require one high school junior and one high school senior to sit on both the Council for Basic Education and Council of Higher Education for their SBOE, but the students have no voting power. 36 The Pennsylvania Association of Student Councils, a statewide student leadership organization that works with administrators and students alike, recommends high school students for the Council of Basic Education. 37 Vermont has two student members on their SBOE, one of whom has voting power upon the second year of their service. 38 The Maryland State Department of Education sponsors the Maryland Association of Student Councils, which nominates one student for the SBOE to serve alongside another governor-appointed student. 39

Some states have explicit laws to encourage or prohibit youth participation. According to a 2014 SoundOut analysis, 14 states have laws that explicitly prohibit students from serving on district school boards. 40 Twenty-five states permit students to sit on district school boards, but that does not mean that all districts within the state choose to include student members. 41

Building demand for youth perspectives

In some states, especially Kentucky and Oregon, youth are pressing the case to have their perspectives considered and are demanding a seat at the table by working outside of existing structures, informing themselves about policies, effectively lobbying legislators, and holding press conferences. 42 For instance, the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, a nonpartisan, nonprofit citizen’s advocacy group in Kentucky, is helping policymakers and educators see the value of youth perspective as part of their larger goal to improve academics and educational equity across the state. 43 The organization has a Student Voice Team of approximately 100 self-selected students ranging from elementary school students to college students. 44 According to the group’s website, it uses “the tools of civil engagement to elevate the voices of young people in education research, policy, and advocacy.” 45

Furthermore, in some states and cities, including Denver and Los Angeles, youth have worked to lower the voting age for school board members to age 16 as a way to encourage student civic engagement and utilize students’ first-hand experience with school-related issues. 46 In Colorado, a coalition of youth advocates were key in convincing a state senator and a state representative to introduce legislation in 2019 that seeks to allow 16- and 17-year-olds to vote in local school board elections. 47

- Gives student representatives real power over state and district policies, including hiring and budgeting

- Gives voting student members equal power to adult members

- Allows students to gain experience with governing bodies

- Fosters open conversation between students and adult decision-makers

- Engages only a few select students

- Often includes students for whom the current education structure is already working

- May not influence change if the student is not a voting member

- Dependent on the structure, risks student representatives not feeling empowered to voice their opinions or to disagree with adult authority figures

- Is less appropriate for younger students

- Give student representatives voting power

- Recruit and seek out diverse candidates to run or be appointed to governing bodies

- Create two or more slots for students

- Schedule meetings at times and locations that are accessible and convenient for students

- Offer training to both youth and adults to foster and build toward a concrete and authentic youth-adult partnership

Case studies

Pittsfield middle high school site council, pittsfield, new hampshire.

Started in 2010, the Pittsfield Middle High School Site Council is a majority-student school governance body with 10 student members, six faculty members, and three community members 48 who are responsible for deciding school policies such as dress codes and class schedules. Students work with teachers and community members to discuss policy changes to address long-standing academic and school climate issues. Pittsfield Middle High School has also implemented other strategies that promote student choice, including shifting to competency-based learning. Since the school adopted some of these approaches, Pittsfield Middle High School’s dropout rate has decreased by more than half, from 3.9 percent in the 2010-2011 school year to just 0.6 percent in the 2016-2017 school year. 49

Montgomery County Public School Board of Education, Maryland

In Maryland, Montgomery County Public Schools’ Board of Education is made up of eight members, one of which is an elected student member with full voting rights. The board addresses a variety of issues, including operating budgets and school building closings. Additionally, the current student board member plans to discuss topics such as affirmative consent and high school dress codes. 50

Boston Student Advisory Committee

In Massachusetts, two representatives from most Boston high schools serve on the Boston Student Advisory Committee (BSAC), which Boston Public Schools (BPS) created to make recommendations to the BPS system’s Boston School Committee. In addition, BPS asks the student representatives to share their work with their peers to make sure that all students are more informed about current district policy debates. According to BPS, the BSAC is “primary vehicle for student voice and youth engagement across the Boston Public Schools.” Participating students receive public-speaking training, learn about community organizing, and are taught how to navigate political situations. At weekly meetings, the BSAC discusses several important issues such as school discipline and climate, BPS budget, student-to-teacher feedback, and school equity. 51

Student governments or councils

Student governments, sometimes called student councils, are comprised of student representatives who weigh in on or oversee school-related matters. The number of students on a student council varies by school. Roles on student councils typically include a president, vice president, treasurer, and secretary, among others. Typically, representatives run campaigns and are elected by their peers. In some instances, elected students or the school administration can appoint students. 52

The responsibilities of student councils are sometimes outlined in a formal framework such as bylaws or a constitution. 53 Student councils typically have no authority over budgeting, school hiring, pay and other personnel matters, discipline, grades, or the length of the school day. They do, however, tend to have shared responsibility for homecoming, dances, and civic and volunteer activities. Often, they have complete authority over student council initiatives, school spirit weeks, fundraising for council projects, staff appreciation, and more. 54 In general, school administrations can assign specific responsibilities or projects to student councils and assign a faculty adviser to them. Student councils can also maintain autonomy and budget authority over the programs under their control. As liaisons between administrators and students, student councils can have a significant effect on school climate.

To make student governments representative of the entire student body, it is important for schools to encourage diverse candidates to run for office. Intentionally diverse student representation encourages discussion of different viewpoints and various student interests.

- Empowers students to make decisions and engage in issues that are important to the student body and school culture

- Fosters leadership development

- Enables students to gain experience with democracy, administration, and communicating with administrators

- Generally involves a small number of students who are elected by their peers and typically have higher social capital

- Leaves the possibility that student council activities are restricted to the responsibility granted by a school and faculty advisers

- Empower student councils to have a voice in consequential school matters

- Consider consulting with student government on important decisions such as school schedules, school budget, hiring, and discipline policy

- Support all students who demonstrate interest in running for student government to cultivate less-likely candidates or structure the council to make it more inclusive of all interested students

- Encourage student councils to undertake initiatives that align with their values and could have a significant and lasting effect on the school community or the community writ large

Weston High School Student Council, Weston, Massachusetts

Each year, Weston High School students elect five representatives from each class along with six elected student officers to represent the student body as the student council. The 26 members plan schoolwide social events. Some of these events raise money for charities that the council chooses. In 2018, the council raised more than $8,000 for Camp No Limits, a camp program for children with physical disabilities. The student council works to develop opportunities for all students to discuss strategies to improve school culture. Each year, two members from the Weston High School council join the Greater Boston Regional Student Advisory Council to represent the school at the state level. 55

Student journalism

Student journalism provides students with a platform to gather information, interview sources, raise issues, and report news. Student journalism can be used to expose problems in a school or community and as an outlet to express students’ opinions. Student journalists now share stories and their ideas using student-led television programs, podcasts, social media, blogs, and most traditionally, newspapers. Student journalism allows students to try their hand at writing and reporting—skills that can help them prepare for their careers. While high schools are more likely to have reporting and editorial teams, some middle and even elementary schools have school newspapers. Some student publications publish monthly; others publish weekly. Middle school and high school students and their schools can even win awards for their journalism. For example, the Journalism Education Association (JEA), an organization dedicated to protecting and enhancing journalism education, offers awards such as the Aspiring Young Journalist Award and the Student Journalist Impact Award. 56 The JEA also offers Journalist of the Year Scholarships to high school seniors who submit digital essays to their state JEA director and go on to a national competition. 57

Teacher advisers often oversee student reporting, although their level of oversight differs significantly by school. In some instances, administrators strictly filter content and limit the topics on which students can report. In fact, in 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that a school district is allowed to censor work in school publications if the writing is poor or if the content does not align with certain values. 58 As a result, similar to professional journalists, students have varying degrees of freedom to select and report on topics. Some student journalists cover controversial issues such as elections, teacher walkouts, safe sex, and school shootings, while other schools only allow students to cover school-based social events and reviews of pop culture. 59

- Enables students to raise issues, start conversations, and express their opinions on issues related to their schools, districts, and state policies

- Allows student journalists to gain practical skills that can give them a leg up in their careers

- Allows students to become more informed about current events

- Enables students to write and report on topics that they find important

- Provides an outlet for students to be recognized for academic and athletic achievement as well as other contributions to the school community

- Leaves decision-making to schools on how much flexibility students have over news production and content

- Requires established structures and resources within each school

- Provide training on writing, reporting, and the best ways to use different media tools to share ideas 60

- Encourage all students to read and discuss student articles in class

- Engage a trusted adviser to help students manage logistics and serve as an advocate for the publication

- Submit student articles to local papers to increase impact and visibility

The Eagle Eye , Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, Parkland, Florida

Students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, manage The Eagle Eye , the student newspaper, with the support of a teacher adviser. Students take a journalism class to learn research and writing skills necessary to contribute to the publication. In the wake of the devastating school shooting in February 2018, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School principal, Ty Thompson, gave The Eagle Eye significant flexibility in how the students covered the event and the following advocacy. The Eagle Eye sensitively and accurately captured the stories of victims in the publication following the tragedy. The Eagle Eye has run articles on local school board elections and an op-ed on why juniors should not be allowed to park in the senior parking lot. 61 While students develop and are responsible for the paper’s content, a teacher adviser helps students navigate challenging issues, copyedit content, and meet publishing deadlines. 62

Student-led conferences

Student-led conferences change the players and the dynamic of the conventional parent-teacher conference. At most schools, individual parents and teachers meet twice during a school year to discuss a student’s progress and brainstorm solutions to academic or behavioral issues. However, the student-led conference invites the student into the conversation and allows them to describe their academic progress and collaborate with teachers and parents to address academic, behavioral, or social challenges. The student-led conference model provides students with a forum to share their work and discuss what they find most difficult and most meaningful in their educational experience.

Teachers and parents can engage students of any age in a conference, but participation will look different depending on the student’s age and development. In most instances, students share a representative portfolio of work that they prepared prior to the conference. A first grader, for example, may use the portfolio of work to explain what they have learned thus far during the year. A fifth grader, on the other hand, may employ the portfolio to explain which learning goals they have yet to master or to develop a plan to complete more homework on time.

- Provides greater transparency for students in understanding the progress they are making and the areas for improvement

- Strengthens communication between parents and guardians and students

- Allows students to demonstrate responsibility and communication skills when sharing about their work

- Requires educators to change their mindset of the traditional teacher-student dynamic to ensure student agency

- Limits the ability of parents and teachers to speak candidly about the challenges a student may have

- May be difficult for students to feel comfortable sharing feedback among teachers, parents, guardians, and other relevant adults

- Create developmentally appropriate guidelines for students to participate in conferences that help build students’ ability to discuss their learning and development

- Reframe learning as a youth-adult partnership to empower both parties to share responsibility in learning

Two Rivers Public Charter School, Washington, D.C.

The staff of Two Rivers Public Charter School believe that students should be in control of their own learning. Student-led conferences allow students to share their learning goals with teachers and parents. 63 The school holds student-led conferences three times per year to collect data, highlight progress, and set future learning goals for students. 64 The school offers resources for students to prepare for the conference, including a handbook and checklist, which help students review important information while still allowing them to customize the conversation to their personal learning goals. 65

“Student-led conferences allow us to take ownership of our learning. Only we know how we are doing and where we are running. There isn’t always going to be an adult there to help us.” –Payton, sixth grade student, Two Rivers Public Charter School, Washington, D.C. 66

Democratic classroom practices

Democratic classroom practices allow students to help shape the structure and climate of their learning environment. Teachers make joint decisions with groups of students, helping students develop skills to collaborate with their peers and teachers. 67 In general, teachers facilitate group conversations with a class to set expectations, solve problems, or make important classroom decisions, including co-creation of curriculum and design and assessment measures. 68 For instance, at the beginning of the school year, students and their teacher can develop rules, norms, and consequences. Throughout the year, the class revisits this agreement, tweaking components to ensure that everyone’s needs are met. When problems arise, the teacher facilitates a discussion, framing the problem in a collective voice.

Students of all ages can participate in group decision-making, but teachers should adjust expectations to meet students’ social development. Democratic classroom practices can also include students providing periodic feedback to their teacher about what is or is not working as it concerns the learning environment.

- Enables changes to be made at the classroom level by individual teachers or schools

- Empowers students by letting them weigh in on how the classroom works

- Increases relevance in learning, which leads to increased student engagement

- Appropriate for very young students

- Fosters a sense of community and collaboration among students, teachers, and administrators

- Limits influence to classrooms and, sometimes, schools

- Requires educators to have a change in mindset, which can be difficult to implement

- Adopt a building-wide democratic, problem-solving approach and shift school structures and processes to allow for schoolwide conversation

- Help teachers develop the mindsets and skills to meaningfully implement this approach in their classrooms

- Ensure that administrators and teachers keep an open mind and adjust decisions based on student input

Responsive classroom

Responsive classroom is a specific approach to democratic classroom practices that seeks to incorporate academic and socioemotional learning and is designed for grades kindergarten through eight. Responsive classrooms, or classes that implement this approach, are “developmentally responsive to their (students) strengths and needs.” 69 Responsive classroom incorporates essential teaching practices—including morning meetings, interactive modeling, positive teacher language, and logical consequences—as well as choices in instruction to help students develop and grow academically, socially, and emotionally. Teachers make time in the beginning and end of the day as well as in academic lessons to work through challenges as a class with an eye toward respecting the social and emotional needs of every student. 70

Youth participatory action research

The action research approach provides students the space and time needed to conduct systematic research, analyze oppressive issues in their schools or communities, and develop solutions to address them. When carried out by students, this type of approach is called youth participatory action research (YPAR) or student action research. 71 In implementing this approach, schools or districts may start by inviting students to form research groups with the guidance of a teacher or school counselor. Often, students receive training on how to develop research questions, collect data, conduct interviews, and advocate for solutions. They then use these skills to conduct deep, collaborative research—with other students, teachers, and/or community members—on issues that can range from increasing access to healthy food to addressing the school-to-prison pipeline. 72 The research process can last a few months to an entire year. At the end of the process, students develop recommendations for social change. Students have the opportunity to present their policy ideas to decision-making bodies, or they can begin to develop strategies on their own to implement their recommendations. Usually, a teacher or other adult acts as a guide or coach to help students navigate the research process and determine how to advocate for and implement change, including facilitating discussions with relevant decision-makers.

Action research is most appropriate for middle school and high school students. It gives participating students the opportunity to address pressing issues in their school and community; moreover, the concrete tasks of action research promote key learning outcomes related to reading, writing, and inquiry. Often, action research occurs outside of existing school structures and can feature collaboration with community groups.

- Enables students to focus on issues that matter most to them and to their communities

- Supports students in developing research and advocacy skills

- Allows for open conversation between students and decision-makers

- Builds civic engagement and sense of empowerment when projects result in positive change

- Helps students learn to work in teams

- Shifts adult perceptions of the capacity of youth to be change agents

- Requires significant time to organize and support

- May be difficult to develop actionable, relevant, and timely solutions when projects are conducted on a part-time basis

- Not as easy to coordinate among younger students

- Make concerted efforts to support students in their idea development, research, and execution

- Guarantee that action research groups have an audience and invite students to present to school leaders or district policymakers

- Create a context where students feel safe to ask critical questions about their school experiences and challenge business-as-usual attitudes and practices

Student Board Challenge 5280, Denver Public Schools

Denver Public Schools’ (DPS) Challenge 5280 invites high school students to participate in action research. In 2014, DPS launched the competition with financial and programmatic support from the Aspen Institute, an international think tank. 73 Today, DPS fully funds and manages the program and has integrated the challenge into DPS’ Student Board of Education. Initially a seven-week program, Challenge 5280 now runs as a yearlong student leadership class and is positioned in the district as a Civic Leadership Development program. In recent years, high school students investigated pressing social justice concerns in their school community and helped institute a range of actions, including requiring implicit bias training for teachers, establishing student hiring committees, and implementing restorative justice practices. 74 Current student research topics address social justice issues such as sexual health and wellness, culturally responsive professional development for teachers, and the empowerment of young men of color. 75 Each SBOE Challenge 5280 team has a coach who is typically a full-time classroom teacher, though a few are guidance counselors and administrative staff.

At the end of the school year, SBOE Challenge 5280 teams present their research and solutions as part of a competition in front of community, city, and district policymakers. Challenge teams also meet with administrative leadership in their schools throughout the year. Almost half of the high schools in the district participate with schools having the autonomy to implement the program based on their specific dynamics. 76 More than half of participating schools offer an elective course on action research to ensure that more students have the time and space to participate. 77

“The growth that comes with understanding the true value of students in education; that students have the voice, strength, and knowledge to enact change in any system, and have just as much right as anyone to do it, especially in education. Without that understanding, I wouldn’t have been able to recognize those values in myself.” –Jua Fletcher, class of 2018 student, Denver South High School 78

Personalized learning

Teachers and schools can give students a voice in what and how they learn through personalizing instruction. Personalized learning tailors at least some of the learning experience based on students’ individual needs, skills, and interests.

Teachers can adapt instruction in different ways. For instance, a teacher can allow students to select topics for projects or reports based on their interests or differentiate instruction based on what students need to master course material. Personalized learning can transform elementary and secondary schools when schools, districts, and states allow students to have greater control over what, how, and at what pace they learn. For example, states or districts may allow schools to change the way students earn credit for courses. Instead of following a regimented scope and sequence, schools may allow students to demonstrate mastery or competency of learning goals in classroom and out-of-school activities that interest them.

- Allows students to explore topics that interest them, which can increase the relevance and engagement of instruction

- Allows change to happen at the classroom level

- Works very well for students who are self-directed and motivated

- Implementation quality can vary widely

- Some programs are overly reliant on technology to provide instruction, leading students to experience too much time in front of screens

- It can isolate students and weaken relationships with other peers that facilitate learning

- Pass state and district policies that create flexibility in the way students progress through learning goals and demonstrate mastery

- Ensure that students are working closely with their peers and adults and that the school and classroom has strong systems for monitoring student progress and ensuring students receive personal attention and remain on track

MC² STEM High School, Cleveland

Students at MC² STEM High School in Cleveland learn through an entirely project-based curriculum that is designed to prepare students for in-demand science, technology, engineering, and math roles in the community. Students drive their own learning by selecting a topic for semester-long, interdisciplinary, theme-based projects. All projects align with Ohio’s state standards and reflect the needs of local industry partners. Throughout the year, students have access to local experts, industry groups, and internships so that each student can tailor their learning to their specific areas of interest. 79

Meaningful implementation of student voice strategies

“We’ve been moved from the kiddie table to the adult table, but our portions remain the same.” –Elijah Jones, 11th grade student, The Tatnall School, Wilmington, Delaware 80

Careful design and implementation of student voice strategies are critical to ensure that any strategy meaningfully incorporates student perspectives and empowers students to influence instruction and policies. The following components can build the foundation for and improve the implementation of any strategy designed to empower students to share their perspective and lead.

- Diverse student perspectives . Student voice is not a monolith. Students have diverse perspectives and needs. Strategies to incorporate student perspectives and position students to lead should try to engage many students, especially traditionally disempowered students who may be struggling to succeed in the current school structures. Incorporating student perspectives is easier to accomplish in student surveys, democratic classroom practices, personalized learning, and student-led conferences that inherently allow more students to participate. Also, YPAR can be designed in ways that target specific subgroups that are not typically heard in decision-making processes. 81

- Clear expectations, goals, and processes for both students and adults. Students will have different levels of input and decision-making power based on the specific strategy, age level of students, or entity such as the school board, school, councils, and more. Adults—administrators, teachers, and policymakers—at all levels should be transparent about the areas in which they are seeking student voice and how they will incorporate student perspectives. 82 Doing so will require that many adults step outside of their comfort zone of control and embrace a new paradigm. By doing so, students can clearly see how their ideas and actions change policies and practice.

- Adult-student trust . Students and adults should respect and value each other’s perspectives and assume best intent. Underlying trust will allow students and adults to work through differences in opinions. Schools can help foster these connections by creating time for adults and students to collaborate and talk outside of specific academic classes. 83

- Scaffolding for students . Many of the strategies listed above are most appropriate for middle or high school students, but schools should build the skills and mindsets needed for students to take initiative, advocate for solutions, and drive change beginning at an early age. Educators can help cultivate student voice by scaffolding some of these strategies for students’ development level. For instance, in student-led conferences, students in the third grade may describe what they have been learning, while students in the seventh-grade may have the ability to share where they are struggling or exceeding expectations.

- Scaffolding for adults. Effective implementation of these practices requires adults to shift their mindset and develop new skills for collaboration. Adults may need support learning how best to adapt structures to facilitate open dialogue and trust among adults and students. 84 They may also benefit from seeing successful strategies in action and hearing from adults who have seen the positive effects of authentic partnership with students.

The following table outlines examples of the ways that schools or policymakers can implement these strategies with varying degrees of significance. The table also highlights the zones of influence for different strategies and the grade-span most effective for each strategy.

Policy recommendations

Schools and policymakers should value student perspectives—student voice—and give students the opportunity to influence instruction and policy decisions by adopting and implementing appropriate strategies.

State level

State policymakers should incorporate student perspectives as they develop and implement policies and encourage schools to empower students to drive their own learning and influence school procedures and practices. To do so, state policymakers should do the following:

- Include a voting student member on the state school board. State school boards should appoint a student member with voting power to the board. State boards should develop a democratic process to select the student and assist the student in soliciting diverse student perspectives to make sure a wide cross section of student opinions inform policy decisions.

- Create student advisory committees for state policymakers. Similar to teacher advisory committees, state policymakers can create student-populated bodies to advise decision-makers on challenges and on policy development and implementation. These committees should meet regularly and discuss consequential matters.

- Require statewide surveys to collect information on students’ attitude toward school and their community and make the results public. More states should require all schools to administer surveys to consider students’ attitudes toward school and their community. States should collect the data, publish the results, and encourage districts to use the information to inform policy changes. States should involve students in data analysis and any subsequent actions.

- Encourage student-centered learning. States can create flexibility in how students can demonstrate mastery, allowing students to learn at their own pace and in ways that align with their areas of interest. To do so, some states are eliminating the use of the Carnegie Unit, the practice of measuring student learning by seat time in each course. For example, New Hampshire eliminated the Carnegie Unit in 2005, and the state allows districts to develop a competency rubric to measure student mastery. 85

District level

Similar to states, school districts and boards should incorporate student perspectives in their decision-making process as well as implement policies that encourage schools to empower students to drive their own learning and influence school policies. To do so, district level policymakers should do the following:

- Support state-required surveys and develop district-level student surveys to gather information about instruction and school climate. Districts should support schools in administering state surveys, if the surveys are required by the state. Districts can supplement that information and develop student surveys on the rigor of instruction, quality of teaching, and school climate while ensuring youth involvement in each step of the process. Districts should publish the school-level data and use the results to create improvement plans and support school leaders. For instance, if several schools struggle with school climate, a district may hire a consultant to help those schools develop a positive behavioral intervention system, develop democratic classroom practices, and find context-specific approaches to improve student-adult relationships.

- Include students on governing bodies and create student advisory committees to engage more student perspectives in important decisions. District school boards should appoint at least one student member with voting power to the board. District boards should develop democratic processes to select the student and help the student representative develop strategies to gain input from diverse student perspectives before weighing in on school board matters. This student advisory group could undertake YPAR or other forms of research about student experiences to inform their policy arguments and recommendations.

- Create specific initiatives to engage student groups that are historically marginalized. While efforts to create strategies to engage all students are important, targeted programming enables specific subgroups such as students of color, students who identify as LGBTQ or students from other marginalized racial or ethnic groups to have a voice. For example, Denver Public Schools has a Young African American and Latinx Leaders group, which addresses systemic inequities facing African American, Latinx, and indigenous administrators, teachers, staff, and students. 86

- Encourage schools to build time for student-educator collaboration and enable personalized learning. Districts should help schools think creatively to shift school schedules to enable students and educators to collaborate outside of instructional time. Districts should also assist schools in restructuring their schedules to allow for project- or inquiry-based learning. This may require schools to create fewer, longer instructional blocks throughout the day rather than the traditional eight 45-minute block schedule. Or districts could allow high schools to offer course credit for projects done in conjunction with community or local industry partners.

- Offer student-led conferences and provide training to teachers on how to conduct them. Student-led conferences can be empowering for students—even very young students—but they involve a shift in the typical teacher-parent communication. Teachers would benefit from district and administrative support in implementing these conferences.

School level

Schools leaders should design schools that foster adult-student trust and communication as well as promote personalized learning. To do so, school leaders should do the following:

- Empower students to drive their learning and foster a positive school climate. Schools should help teachers personalize learning and customize curriculum to meet the interests and needs of each student. Teachers and schools can help students to critically consider their environment and effectively articulate challenges and solutions by adopting democratic classroom practices. For older students, this interaction would include action research. Schools can help students take the reins of their learning by allowing students to lead parent conferences and develop their own personalized learning plans.

- Administer student surveys in a strategic manner to increase participation rates, utilize the results to inform strategy and operations, and create informal information-gathering tools and polls to inform classroom decisions. If the state or district requires a survey, school administrators can access those results, partner with students to set goals for improvement, and develop strategies to meet those goals with student input. Administrators should highlight the survey results and the strategy for improvement with teachers, students, and parents. Students should have time to complete the surveys during class in order to increase participation rates. School leaders can include students in the process of analyzing, reporting, and utilizing the student survey data to improve instruction or climate. Also, schools or teachers can create their own surveys or polls to inform school or classroom decisions.

- Create student newspapers and empower student journalists. There are many new and exciting ways for students to explore issues of interest to them and share them with their community. Schools should explore creating podcasts, blogs, and more to provide students with avenues to share their opinions and gain valuable skills. Administrators should provide training and guidance but should not place restrictions on content whenever possible. Schools should devote resources to student journalism and work with students to create an effective distribution strategy.

- Provide student governments with meaningful authority . Schools should consider expanding the scope of student council responsibilities to include weighing in on the core issues affecting the student experience such as the school schedule, budget, discipline code, curriculum, and hiring decisions. Schools should also encourage student governments to undertake important initiatives that would improve the school culture and community. School administrators should empower student-led governments by encouraging a diverse pool of students to run for office, including marginalized, underserved, and less extroverted students. School administrators can also suggest alternatives to the traditional voting system process that would serve to include more students from the groups listed above and would encourage any interested student to participate. School administrators should also carve out time for candidates to campaign and allow student-led governments to organize important school functions.

- Offer professional development to help teachers and administrators shift mindsets and build skills to effectively implement student voice strategies. School administrators benefit from training that helps them implement structures and communication techniques that build trust between students and educators. Adults may need to shift mindsets around existing power structures that tend to invalidate student opinions and contributions. In order to shift this paradigm, teachers and administrators must be open to change.

- Restructure school schedules to build in time for students and teachers to share perspectives and discuss school policies. To effectively incorporate student perspectives in school policies, students and teachers need time to discuss challenges and develop solutions related to instruction, school climate, and other school policies.

Studies show that people who take initiative and demonstrate leadership skills are more likely to succeed in their careers. 87 Yet schools do not always foster those very qualities—sometimes they even stifle them. Numerous surveys show that students do not feel engaged in school, especially in later years, which can be an impediment to success in their academic career. Therefore, ensuring that all students are engaged by increasing access to rigorous coursework and providing the necessary supports for success is paramount. Equally important is the need to ensure students have a voice in their education. Schools should empower students to influence instruction, school climate, and education policies. In addition, teachers, school administrators, and policymakers should adopt practices or structures that allow students to share their perspectives—and make their voices heard.

As noted in this report, many of the strategies to incorporate student voice are most effective when teachers or policymakers adopt them in combination with other strategies. However, schools and policymakers do not have to do everything at once. They can build upon existing strategies over time.

When it comes to strategy, implementation matters. Schools and policymakers should empower all students rather than a select few. Moreover, there must be a clear purpose to any student voice strategy in order to increase buy-in of adults and students. Finally, adults and students must trust each other and develop skills to build collaboration.

Across the country there are various examples where schools, districts, and states are meaningfully incorporating student perspectives. They are not only empowering students to share their perspectives—but they are also encouraging them to actively partner in transforming schools. Clearly, given their experience, more schools, districts, and states should follow suit.

About the authors

Meg Benner is a senior consultant at the Center for American Progress.

Catherine Brown is a senior fellow at the Center.

Ashley Jeffrey is a policy analyst for K-12 Education at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge several people who provided guidance and insights for this report. Helen Beattie, founder and executive director of UP for Learning; Seyma Dagistan, Ph.D. student in educational theory and policy at Pennsylvania State University (PSU); Ben Kirshner, associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder; and Dr. Dana Mitra, professor of education in the Educational Theory and Policy Program at PSU, who generously reviewed and provided invaluable feedback on an earlier version of this report.

The authors would also like to thank Dr. Aaliyah El-Amin, lecturer and researcher at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE); Dr. Gretchen Brion-Meisels, lecturer at the HGSE; Dr. Meira Levinson, professor of education at the HGSE; Solicia Lopez, director of Denver Public Schools; Mark Murphy, founder of GripTape and former Delaware secretary of education; and Eric Toshalis, senior director of impact at KnowledgeWorks for connecting with them to discuss their research and work in the field.

- Valerie J. Calderon and Daniela Yu, “Student Enthusiasm Falls as High School Graduation Nears,” Gallup, June 1, 2017, available at https://news.gallup.com/opinion/gallup/211631/student-enthusiasm-falls-high-school-graduation-nears.aspx .

- The New Teacher Project, “The Opportunity Myth: What Students Can Show Us About How School Is Letting Them Down—and How to Fix It” (2018), available at https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf .

- John M. Bridgeland, John J. Dilulio Jr., and Karen Burke Morison, “The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts” (Washington: Civic Enterprises, 2006), available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED513444.pdf ; Eric Toshalis and Michael J. Nakkula, “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice” (Boston: Jobs for the Future, 2012), available at https://jfforg-prod-prime.s3.amazonaws.com/media/documents/Motivation_Engagement_Student_Voice_0.pdf ; Dana L. Mitra, “Student Voice in School Reform: Reframing Student-Teacher Relationships,” McGill Journal Of Education 38 (2) (2003): 289–304, available at http://mje.mcgill.ca/article/viewFile/8686/6629; Teri Dary and others, “Weaving Student Engagement Into the Core Practices of Schools” (Clemson, SC: National Dropout Prevention Center/Network, 2016), available at http://dropoutprevention.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/student-engagement-2016-09.pdf .

- Toshalis and Nakkula, “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice”; Mitra, “Student Voice in School Reform”; Adam Fletcher, “Intro to Meaningful Student Involvement,” SoundOut, January 31, 2015, available at https://soundout.org/intro-to-meaningful-student-involvement-2/ ; Jean Rudduck, “Student Voice, Student Engagement, and School Reform,” in International Handbook of Student Experience in Elementary and Secondary School (2007), available at https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F1-4020-3367-2_23 .

- Bridgeland, Dilulio Jr., and Morison, “The Silent Epidemic.”

- Toshalis and Nakkula, “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice”; Jerusha O. Conner, Rachel Ebby-Rosin, and Amanda Brown, Student Voice in American Education Policy (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 2015).

- Stell Simonton, “Youth Organizations Oppose the Administration Ending DACA,” Youth Today, September 5, 2017, available at https://youthtoday.org/2017/09/youth-organizations-support-keeping-dreamers-in-u-s-oppose-end-to-daca/ .

- Advancement Project, “Philadelphia Student Union, Advancement Project National Office Pen Policy 805 Opposition Letter to Philadelphia Board of Education” Press release, February 28, 2019, available at https://advancementproject.org/news/philadelphia-student-union-advancement-project-national-office-pen-policy-805-opposition-letter-to-philadelphia-board-of-education/ ; Nathaniel Bryan, “White Teachers’ Role in Sustaining the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Recommendations for Teacher Education,” The Urban Review 49 (2) (2017): 326–345, available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-017-0403-3 ; Nancy A. Heitzeg, “Education or Incarceration: Zero Tolerance Policies and the School to Prison Pipeline,” Forum on Public Policy Online 2 (2009): 1–21, available at https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ870076 ; Shannon D. Snapp and others, “Messy, Butch, and Queer: LGBTQ Youth and the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” Journal of Adolescent Research 30 (1) (2014): 57–82, available at https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558414557625 ; Matt Cregor and Damon Hewitt, “Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline: A Survey from the Field,” Poverty & Race 20 (1) (2011): 5–7, available at http://www.indiana.edu/~atlantic/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/Cregor-Hewitt-Dismantling-the-School-to-Prison-Pipeline-A-Survey-from-the-Field.pdf .

- Voices of Youth in Chicago Education, “About SB 100,” available at http://voyceproject.org/campaigns/campaign-common-sense-discipline/sb100/ (last accessed July 2019).

- Conner, Ebby-Rosin, and Brown, Student Voice in American Education Policy .

- Dana Mitra and others, “The role of leaders in enabling student voice,” Management in Education 26 (3) (2012): 104–112, available at https://www.academia.edu/2005772/The_role_of_leaders_in_enabling_student_voice ;

- Toshalis and Nakkula, “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice.”

- Dana L. Mitra and Steven Jay Gross, “Increasing Student Voice in High School Reform: Building Partnerships, Improving Outcomes,” Educational Management Administration and Leadership 37 (4) (2009): 522–543, available at http://www.buildingpublicunderstanding.org/assets/files/increasingstudentvoiceinhighschoolreform.pdf .

- Toshalis and Nakkula, “Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice”; Mitra and Gross, “Increasing Student Voice in High School Reform”; Dana Mitra, “Student Voice in Secondary Schools: The Possibility for Deeper Change,” Journal of Educational Administration 56 (5) (2018): 473–487, available at https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/JEA-01-2018-0007 .

- Helen Beattie, “Four Feet on the Ground: The Youth-Adult Partnership ‘Teeter-totter Effect,’” UP for Learning, November 27, 2018, available at https://www.upforlearning.org/four-feet-on-the-ground-the-youth-adult-partnership-teeter-totter-effect/ ; UP for Learning, “Youth-Adult Partnership Rubric,” available at https://www.upforlearning.org/resource-center/resources/yap-rubric/ (last accessed June 2019).

- Center for Prevention Research and Development, “Illinois Youth Survey: 2018 Frequency Report: State of Illinois” (2018), available at https://iys.cprd.illinois.edu/UserFiles/Servers/Server_178052/File/state-reports/2018/Freq18_IYS_Statewide.pdf .

- Martin R. West, Hans Fricke, and Libby Pier, “Trends in Student Social-Emotional Learning: Evidence From the CORE Districts” (Stanford, CA: Policy Analysis for California Education, 2018), available at https://www.edpolicyinca.org/sites/default/files/SEL_Trends_Brief_May-2018.pdf .

- Samantha Batel, Scott Sargrad, and Laura Jimenez, “Innovation in Accountability: Designing Systems to Support School Quality and Student Success” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2016), available at https://americanprogress.org/issues/education-k-12/reports/2016/12/08/294325/innovation-in-accountability/ .

- Angela Duckworth, “Don’t Grade Schools on Grit,” The New York Times, March 26, 2016, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/27/opinion/sunday/dont-grade-schools-on-grit.html?_r=0 .

- Batel, Sargrad and Jimenez, “Innovation in Accountability.”

- NYC Department of Education, “NYC School Survey Citywide Results.”

- UP for Learning, “Youth-Adult Partnership Rubric.”

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “CDC Youth Risk Behavior Surveys,” available at https://www.cdc.gov/features/dsyouthmonitoring/index.html (last accessed June 2019).

- UP for Learning, “YATST Launches New Identity” (2013), available at https://www.upforlearning.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/UPforlearning-spring2013-web_FINALONE.pdf .

- D.C. State Board of Education, “Student Advisory Committee,” available at https://sboe.dc.gov/studentvoices (last accessed June 2019); D.C. State Board of Education, “DC State Board of Education Seeks Student Representatives and Student Advisory Committee Members for the 2015-2016 School Year,” available at https://sboe.dc.gov/release/dc-state-board-education-seeks-student-representatives-and-student-advisory-committee (last accessed June 2019).

- The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Students As Partners: Integrating Student Voice in the Governing Bodies of Kentucky Schools” (2016), available at http://prichardcommittee.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Students-as-Partners-final-web.pdf .

- The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Students as Partners”; Dana L. Mitra, “Student Voice or Empowerment? Examining the Role of School-Based Youth-Adult Partnerships as an Avenue Toward Focusing on Social Justice,” International Electronic Journal for Leadership in Learning 10 (2006): 1–17, available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291739211_Student_voice_or_empowerment_Examining_the_role_of_school-based_youth-adult_partnerships_as_an_avenue_toward_focusing_on_social_justice .

- The Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Students as Partners.”

- Patricia Ruggiano Schmidt, “Culturally Responsive Instruction: Promoting Literacy in Secondary Content Areas” (2005), available at https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ ED489509.pdf.

- Adam Fletcher and Adam King, “SoundOut Guide to Students on School Boards” (Olympia, WA: SoundOut, 2014), available at https://adamfletcher.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/SoundOut-Guide-to-Students-on-School-Boards.pdf .

- Pennsylvania State Board of Education, “Student Representation,” available at https://www.stateboard.education.pa.gov/TheBoard/StudentMembers/Pages/default.aspx (last accessed June 2019).

- Pennsylvania Association of Student Councils, “About Us,” https://www.pasc.net/about-us (last accessed June 2019); Pennsylvania State Board of Education, “Student Representation.”

- Vermont State Board of Education, “Membership,” available at https://education.vermont.gov/state-board-councils/state-board#state-board-membership (last accessed June 2019).

- Maryland Association of Student Councils, “What is MASC?”, available at https://mdstudentcouncils.org/index.php/about-us/what-is-masc/ (last accessed June 2019).

- Fletcher and King, “SoundOut Guide to Students on School Boards.”

- Oregon Student Voice, “Empower,” available at https://www.oregonstudentvoice.org/empower (last accessed June 2019); Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Prichard Committee Vision and Mission,” available at http://prichardcommittee.org/ (last accessed June 2019); Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Students As Partners.”

- Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, “Home,” available at http://prichardcommittee.org/ (last accessed June 2019).

- The Groundswell Initiative, “More About the Student Voice Team,” available at http://groundswell.prichardcommittee.org/student-voice/ (last accessed June 2019).

- Erica Meltzer, “Should Colorado Teens Get A Vote in School Board Elections? These Legislators Think So,” The Denver Post, March 28, 2019, available at https://www.denverpost.com/2019/03/28/teen-voting-colorado-school-board-elections/ ; City News Service, “LAUSD to Study Lowering Voting Age for School Board Elections,” April 24, 2019, available at https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/LAUSD-Voting-Age-School-Board-Elections-508991391.html .

- Meltzer, “Should Colorado Teens Get A Vote in School Board Elections? These Legislators Think So.”

- Pittsfield School District, “Site Council Overview,” available at https://www.pittsfieldnhschools.org/pmhs/site-council/ (last accessed June 2019).

- Emelina Minero, “A Town Helps Transform Its School,” Edutopia, July 18, 2017, available at https://www.edutopia.org/article/town-helps-transform-school-emelina-minero ; New Hampshire Department of Education, “Dropouts and Completers,” available at https://www.education.nh.gov/data/dropouts.htm#dropouts (last accessed June 2019).