- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 03 Oct 2023

- What Do You Think?

Do Leaders Learn More From Success or Failure?

There's so much to learn from failure, potentially more than success, argues Amy Edmondson in a new book. James Heskett asks whether the study of leadership should involve more emphasis on learning from failure? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Sep 2023

Thriving After Failing: How to Turn Your Setbacks Into Triumphs

When we slip up, we are often filled with shame, and our instinct is to hide. Instead, people and businesses should applaud smart risk-taking, even when things don't work out, and closely examine their failures to learn from them, says Amy Edmondson.

Failing Well: How Your ‘Intelligent Failure’ Unlocks Your Full Potential

We tend to avoid failure at all costs. But our smarter missteps are worthwhile because they can force us to take a different path that points us toward personal and professional success, says Amy Edmondson.

- 03 Oct 2022

- Research & Ideas

Why a Failed Startup Might Be Good for Your Career After All

Go ahead and launch that venture. Even if it fails, the experience you gain will likely earn you a job that's more senior than those of your peers, says research by Paul Gompers.

- 30 Oct 2019

How to Recover Gracefully After Shutting Down Your Startup

It’s hard to call it quits on a business venture, but entrepreneurs can wind down a struggling startup while keeping their reputations and sanity intact, says Tom Eisenmann. The first step is knowing when to accept defeat. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 27 Feb 2019

The Hidden Cost of a Product Recall

Product failures create managerial challenges for companies but market opportunities for competitors, says Ariel Dora Stern. The stakes have only grown higher. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Jan 2018

- Working Paper Summaries

Creating the Market for Organic Wine: Sulfites, Certification, and Green Values

Certified organic wine remains a tiny percentage of the global wine market. This paper provides a case study of failed new category creation, analyzing the challenges for the organic wine market over time, including overcoming an initial reputation for quality, wines being labeled with multiple names (“organic,” “biodynamic,” “natural”), and competing certification schemes.

- 17 Jun 2015

- Lessons from the Classroom

Excellence Comes From Saying No

In a new course designed by Frances Frei and Amy Schulman, business and law students help each other define and achieve their own interpretations of success. Lesson one: You can't be great at everything. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 Aug 2012

How to Sink a Startup

Noam Wasserman, author of the recently released book "The Founder's Dilemmas: Anticipating and Avoiding the Pitfalls That Can Sink a Startup," discusses ill-advised entrepreneurial behavior. From the HBS Alumni Bulletin. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Jun 2011

Why Leaders Lose Their Way

Bill George discusses how powerful people lose their moral bearings. To stay grounded executives must prepare themselves to confront enormous complexities and pressures. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 07 Mar 2011

Why Companies Fail—and How Their Founders Can Bounce Back

Leading a doomed company can often help a career by providing experience, insight, and contacts that lead to new opportunities, says professor Shikhar Ghosh. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Feb 2011

Clay Christensen’s Milkshake Marketing

Many new products fail because their creators use an ineffective market segmentation mechanism, according to HBS professor Clayton Christensen. It's time for companies to look at products the way customers do: as a way to get a job done. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 08 Nov 2010

How to Fix a Broken Marketplace

Alvin E. Roth was a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Economic Science this week for his Harvard Business School research into market design and matching theory. This article explores his research. Key concepts include: Successful marketplaces must be "thick, uncongested, and safe." Sufficient "thickness" means there are enough participants in the market to make it thrive. "Congestion" is what can happen when markets get too thick too fast: there are heaps of potential players, but not enough time for transactions to be made, accepted, or rejected effectively. "Safety" refers to an environment in which all parties feel secure enough to make decisions based on their best interests, rather than attempts to game a flawed system. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 23 Sep 2009

Operational Failures and Problem Solving: An Empirical Study of Incident Reporting

Operational failures occur within organizations across all industries, with consequences ranging from minor inconveniences to major catastrophes. How can managers encourage frontline workers to solve problems in response to operational failures? In the health-care industry, the setting for this study, operational failures occur often, and some are reported to voluntary incident reporting systems that are meant to help organizations learn from experience. Using data on nearly 7,500 reported incidents from a single hospital, the researchers found that problem-solving in response to operational failures is influenced by both the risk posed by the incident and the extent to which management demonstrates a commitment to problem-solving. Findings can be used by organizations to increase the contribution of incident reporting systems to operational performance improvement. Key concepts include: Operational failures that trigger more financial and liability risks are associated with more frontline worker problem-solving. By communicating the importance of problem-solving and engaging in problem-solving themselves, line managers can stimulate increased problem-solving among frontline workers. Even without managers' regular engagement in problem-solving, communication about its importance can promote more problem-solving among frontline workers. By explaining some of the variation in responsiveness to operational failures, this study empowers managers to adjust their approach to stimulate more problem-solving among frontline workers. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Jan 2009

Risky Business with Structured Finance

How did the process of securitization transform trillions of dollars of risky assets into securities that many considered to be a safe bet? HBS professors Joshua D. Coval and Erik Stafford, with Princeton colleague Jakub Jurek, authors of a new paper, have ideas. Key concepts include: Over the past decade, risks have been repackaged to create triple-A-rated securities. Even modest imprecision in estimating underlying risks is magnified disproportionately when securities are pooled and tranched, as shown in a modeling exercise. Ratings of structured finance products, which make no distinction between the different sources of default risk, are particularly useless for determining prices and fair rates of compensation for these risks. Going forward, it would be best to eliminate any sanction of ratings as a guide to investment policy and capital requirements. It is important to focus on measuring and judging the system's aggregate amount of leverage and to understand the exposures that financial institutions actually have. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 31 Mar 2008

JetBlue’s Valentine’s Day Crisis

It was the Valentine's Day from hell for JetBlue employees and more than 130,000 customers. Under bad weather, JetBlue fliers were trapped on the runway at JFK for hours, many ultimately delayed by days. How did the airline make it right with customers and learn from its mistakes? A discussion with Harvard Business School professor Robert S. Huckman. Key concepts include: JetBlue's dependence on a reservations system that relied on a dispersed workforce and the Web broke down when thousands of passengers needed to rebook at once. A crisis forces an organization to evaluate its operating processes rapidly and decide where it needs to create greater formalization or structure. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 22 Aug 2005

The Hard Work of Failure Analysis

We all should learn from failure—but it's difficult to do so objectively. In this excerpt from "Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently)" in Long Range Planning Journal, HBS professor Amy Edmondson and coauthor Mark Cannon offer a process for analyzing what went wrong. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 12 Jul 2004

Enron’s Lessons for Managers

Like the Challenger space shuttle disaster was a learning experience for engineers, so too is the Enron crash for managers, says Harvard Business School professor Malcolm S. Salter. Yet what have we learned? Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

Determinants of Early-Stage Startup Performance: Survey Results

In this study of 470 founders/CEOs and their management practices, startups that employ lean startup techniques had better valuation outcomes. So did ventures that balanced hiring for skill versus attitude and, more broadly, made early efforts to professionalize human resource management.

Build A Profitable EComm Business For Just $1

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

A magazine for young entrepreneurs

The best advice in entrepreneurship

Subscribe for exclusive access, what these 4 startup case studies can teach you about failure.

Written by Jonathan Chan | December 6, 2020

Comments -->

Get real-time frameworks, tools, and inspiration to start and build your business. Subscribe here

Failure hurts.

Watching something you’ve poured endless amounts of time and energy in, only to see it crumble before you will hurt like hell. It’ll be like a physical punch to the gut, and it will paralyze you. It’s no wonder that entrepreneurs avoid failure like the plague.

A startup can go under for a variety of reasons. While founders can stand around and point fingers at each other, attribute it to forces outside of their control, or just blame bad luck. The reality is that startup failure is from a refusal to acknowledge problems until the ship is already sinking.

The reality of the situation is you are more likely to fail than you are to succeed. If you’re defining startup failure as the inability to deliver on the projected return of investment, then 95% of startups are failures.

But there is no greater teacher than failure.

If you’re going to be an entrepreneur then you better get used to failing, it will become an inevitable part of your life. Don’t run from it, embrace it, and see what lessons you can learn from it.

By analyzing the post-mortems of various failed startups here are the expected and not-so-expected reasons why they failed and what you can learn from their mistakes. Watch out for those icebergs.

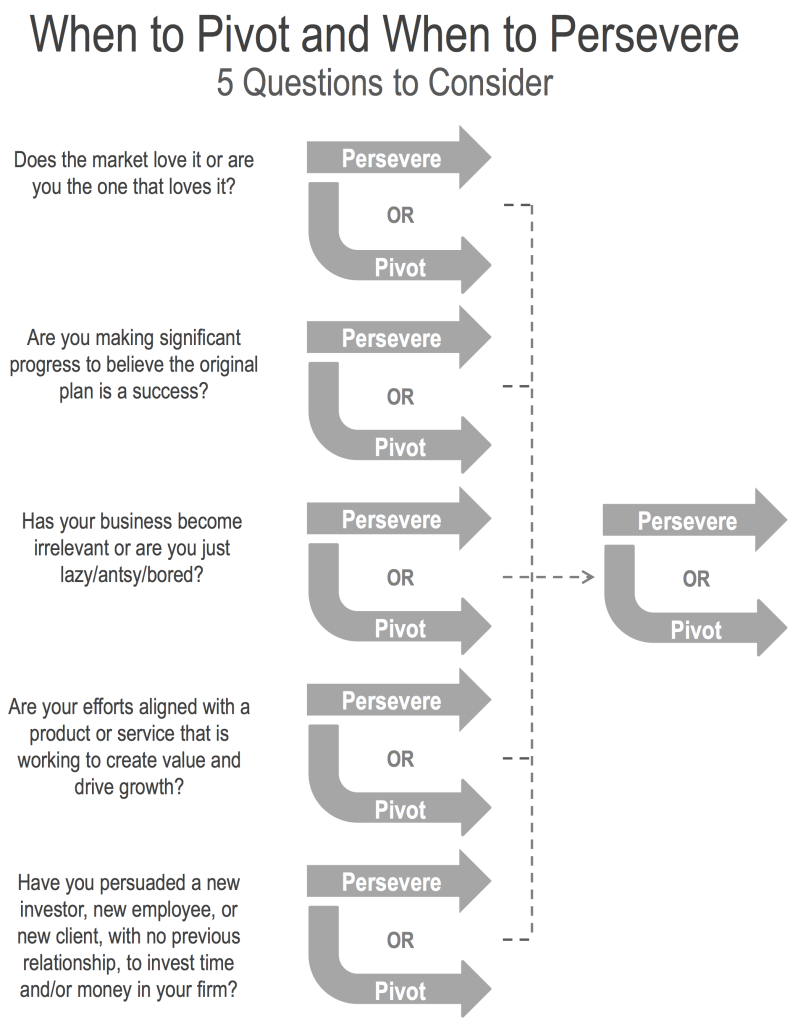

Be Wary of the Pivot

Fab was once known as ‘ the world’s fastest-growing startup ’ and was valued at over at $1 billion before it ultimately crashed.

Fab underwent a variety of changes from an LGBT social network, to a daily flash sales site, to ‘the world’s design store’, before finally being sold off to PCH, for a reported $15 million in cash and stock .

Fab is both a success story and a cautionary tale to entrepreneurs about the risks of pivoting. A pivot generally means that a business is looking to find a fresh perspective and vision to prevent itself from growing stagnant.

Hypothetically a startup should constantly be evaluating data: measuring the market, contemplating new strategies, testing new products. A pivot allows a business to forge ahead in a new direction when either the opportunity is clear, or the current strategy is failing.

“Once we made the decision to pivot, we committed to doing one thing and doing it well. No distractions.” – Jason Goldberg, cofounder and CEO of Fab.

Fab was originally known as Fabulis an LGBT social networking site before pivoting wonderfully into a daily flash sales site for independent artists. Cofounders Jason Goldberg and Bradford Shellhammer admitted to themselves that Fabulis wasn’t turning out to be the success that they hoped, being stuck at 150,000 users for the last few months. It was time to pivot.

The data they had gathered from Fabulis illuminated a real hole in the design market. People were looking for an easy and accessible way to purchase unique and interesting designerwear.

So, they pivoted and became a daily flash sales site for designer housewares, accessories, clothing, and jewelry. The move paid off with Fab growing to over 10 million users and reportedly generating more than $200,000 every day.

Two years later after the initial pivot, despite a shaky business model, Fab decided to pivot again. This time looking to become a designer alternative to Amazon and IKEA. Coupled with a failed attempt to expand into the European market, Fab began its spectacular fall.

READ MORE: Is Your Business Not Making Enough Money? Here’s How to Fix It

The first and foremost requirement for a pivot to truly succeed is it must solve a major problem. At the time Fab was a hugely successful company, despite the fact that the daily flash sales model wasn’t sustainable in the long-term, choosing to drastically scale down their product offerings moved too far from their identity as a designer store. Fab ultimately created another problem while prematurely trying to solve another.

It’s only natural for a struggling startup to pivot, especially when the alternative is to remain stagnant and unprofitable. However as Fab demonstrated, pivoting for the sake of pivoting, or to expand on a shaky business model will almost always guarantee disaster for any entrepreneur out there. No matter how much money you’ve raised.

READ MORE: How Competitive Collaboration Can Boost Your Business

Too Ambitious, Too Fast

At its peak, in 1999, it was valued at $1.2 billion. Two years later they filed for bankruptcy, laid off 2000 employees, and closed up shop. Webvan could potentially be considered a startup ahead of its time, their vision was a home-delivery service for groceries, where customers could order their groceries online, but that’s not where the problem lies.

15 years later it’s still being studied by business schools around the world as a forewarning against excess and ambition.

Webvan can also be considered a product of its time, the result was that it followed the ‘Get Big Fast’ (GBF) business model that every other startup was religiously following at the time. In 1999 Webvan announced they would expand to 26 major cities.

The following two years became a logistical nightmare with Webvan ultimately losing a total of $830 million before filing for bankruptcy.

“Webvan committed the cardinal sin of retail, which is to expand into new territory before we had demonstrated success in the first market. In fact, we were busy demonstrating failure in the Bay Area market while we expanded into other regions,” said Mike Moritz, former Webvan board member, and partner at Sequoia Capital.

READ MORE: How to Make Money With Your Email List

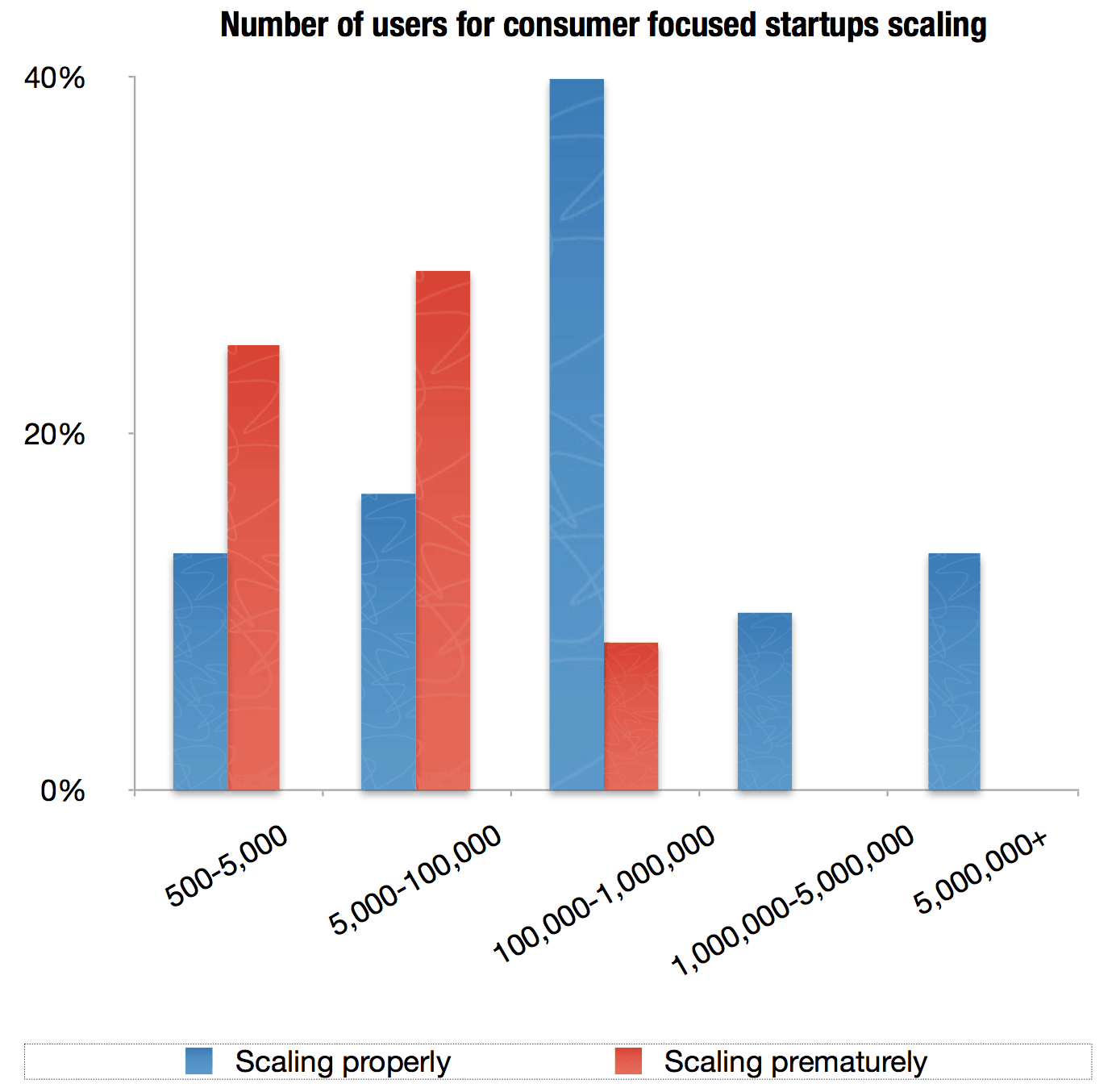

At some point, every successful startup will have to start scaling up and expanding their business. It seems like common sense, but expansion should only be undertaken when a business model has first proven to be successful.

A few rules of thumb are that a scalable business model should be flexible to be able to adapt to different market conditions, core users and customers are evaluated and understood, and the business model should be able to operate without your direct supervision. Common sense right?

Yet according to the Startup Genome Project’s survey of over 3200 startups , 74% of startup failures can be attributed to premature scaling. Another key finding was that startups, on average, need 2-3 times longer to validate their market than the founders expect. This underestimation of appropriate timelines applies unnecessary pressure on founders to scale prematurely.

Despite early validation, Webvan failed to consistently evaluate the data. If they had paid closer attention then they would’ve seen that their business model was shaky and could not possibly support their desired plans for expansion.

It’s only natural for entrepreneurs to want to grow their business. But as Webvan learned, it’s important to grow your business for the right reasons. To pay attention to the data at hand, and never grow for the sake of growth.

Be Wary of Who You Get in Bed With

Pretty Young Professional was founded by four colleagues at McKinsey, a global consultancy firm, who noticed the lack of resources for young women in the world of entrepreneurship.

It had a simple vision, to provide a weekly newsletter and cultivate a community for young female entrepreneurs. All four were coworkers, friends even, who shared a similar passion and vision. A meeting was held; positions and equity were decided amongst themselves and written on a notepad. And that’s when the trouble began.

READ MORE: How to Build a Profitable Marketing Strategy

Kathryn Minshew, co-founder, and CEO of Pretty Young Professional said that “it came down to some pretty fundamental differences of opinion around where the business should be heading. I think, naively, we assumed that if we kicked the can down the road on some of those things, we’d be able to sort them out.”

Despite the years you’ve shared together and the many years of in-jokes you have, conventional wisdom dictates that it’s a bad idea to mix business with friends.

A study by the University of Auckland Business School found that while maintaining strong friendships with co-workers generally improves work productivity and morale it also creates a dilemma when trying to reconcile personal relationships with professional decision-making.

In business, it’s required that you have to make the logical and necessary decisions in order to benefit your company, even at the cost of personal friendships.

11 months in, the four founders of Pretty Young Professional had split into two camps due to differences in opinion, and a coup was staged. The legality of the original document was called into question, Minshew was hit with a lawsuit and called to step down as CEO, and the editorial team of Pretty Young Professional had their site and email access cut. The company quickly collapsed despite calls from excited investors and a thriving user base.

While it is possible to work with friends and family, it requires completely honest communication, both parties must understand that it really is nothing personal, and, perhaps most importantly, vest your ownership. It’s always best practice to ensure that you legally protect yourself and your assets, a promise between friends rarely holds up in the court of law.

READ MORE: 5 Best Sales Funnel Software Tools to Power Your Business

The Double-Edged Sword of SEO

The premise was simple, to help parents find tutors for their kids online. By 2013 they had over 7000 tutors signed up on their platform and has raised an estimated $1.8 million. Then the rug was swept out from under then and they closed down a few months later, after 3 years in operation.

It appeared that Tutorspree was doing everything right, it had managed to raise an impressive amount of capital from heavyweight investors like Sequoia Capital and Lerer Ventures. They were scaling at a decent pace, albeit not as fast as they wanted, and the business model was proving to be profitable.

However, it fell apart in March of 2013 when Google changed its algorithm and Tutorspree found their traffic reduced by 80% overnight . While this normally wouldn’t cripple a business, it was a catastrophe for Tutorspree. SEO was baked into their business model from the very start and almost all of their customer acquisitions originated from SEO.

“Nor is the largest lesson for me that SEO shouldn’t be part of a startup’s marketing kit. It should be there, but it has to be just one of many tools. SEO cannot be the only channel a company has, nor can any other single-channel serve that purpose.” – Aaron Harris, co-founder, and CEO of Tutorspree.

READ MORE: How to Develop Powerful Business Core Values and Mission Statements

There are many different types of SEO practices, but SEO is essentially improving the visibility and authority of a website by having it rank higher on search engine listings. The entrepreneurial community itself is very divided on the merits of SEO.

The issue with Tutorspree wasn’t whether or not it used SEO effectively or ineffectively. The issue was that due to its effectiveness, the founders became blind to other models of customer acquisition and developed an overreliance on a model they had absolutely no control over.

Google’s algorithm constantly changes and there’s no telling how it will ultimately affect your website’s ranking. Google has consistently proven to burn anyone that chooses to rely on SEO as their main strategy.

It should go without saying that you shouldn’t be putting all your eggs into one basket. Entrepreneurs should invest half their marketing into a high-risk strategy, and the other half in a proven consistent strategy, albeit with a lower return on investment. When it comes to business, you can either live or die by the sword or just be smart and carry a shield.

READ MORE: Building the Perfect Sales Funnel for Your Shopify Store

Failure is difficult to handle, but there is no better teacher. Although every business listed failed spectacularly, all of their founders got back up, dusted themselves off, and forged ahead to eventual success.

While it’s easy to see all the mistakes you made in hindsight, don’t let yourself get to that point. Failure can be seen a mile away if you’re paying close enough attention, even if it means asking yourself some uncomfortable questions. A lot of businesses could have been saved if just the smallest amount of preparation was undertaken, or if founders had just a little bit more patience.

Is there a bigger startup failure that you’ve heard about? We love case studies! Let us know in the comments below.

About Jonathan Chan

Jonathan "JC" Chan is the first Content Crafter at Foundr Magazine. When not writing about anything and everything to do with startups, entrepreneurship, and marketing, JC can be found pretending to be the next MMA star at the gym. He has also contributed to outlets such as Huffington Post , Social Media Examiner , MarketingProfs , Hubspot and more. Make sure you connect with him on LinkedIn !

Related Posts

How Zeb Evans Built ClickUp from Life-Threatening Moments — Exclusive

Simon Sinek: Who’s the Man Behind the Personal Brand?

What Do You Learn in Business School? (Behind the Scenes Look)

What Is the 80/20 Rule? A Guide to Saving Time and Money.

The Best Business Networking Apps for You

How to Be Confident: 8 Data-Backed Ways to Overcome Imposter Syndrome

4 Science-Backed Goal Setting Strategies to Grow Your Business

How to Monetize a Personal Brand with Brand Builders Group’s Rory Vaden

How to Build a Personal Brand to Skyrocket Your Business

Single Tasking: How to Improve Your Focus and Productivity

Why ‘Dormant’ Connections May Be the Most Powerful Network You Have

CEO Nathan Chan Reflects on the 10th Anniversary of Foundr

Analog Methods For Getting Things Done—Superpower Your Productivity With Pen and Paper

5 Reasons Why You Need a Business Coach

How To Be A Better Public Speaker

FREE TRAINING FROM LEGIT FOUNDERS

Actionable Strategies for Starting & Growing Any Business.

- 1000+ lessons.

- Customized learning.

- 30,000+ strong community.

The anatomy of business failure: A qualitative account of its implications for future business success

European Journal of Management and Business Economics

ISSN : 2444-8494

Article publication date: 3 July 2017

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the aftermath of business failure (BF) by addressing: how the individual progressed and developed new ventures, how individuals changed business behaviors and practices in light of a failure, and what was the effect of previous failure on the individual’s decisions to embark on subsequent ventures.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors resort to qualitative methods to understand the aftermath of BF from a retrospective point of a successful entrepreneur. Specifically, the authors undertook semi-structured interviews to six entrepreneurs, three from the north of Europe and three from the south and use interpretative phenomenological analysis.

The authors found that previous failure impacted individuals strongly, being shaped by the individual’s experience and age, and their perception of blame for the failure. An array of moderator costs was identified, ranging from antecedents to institutions that were present in the individual’s lives. The outcomes are directly relatable to the failed experience by the individual. The authors also found that the failure had a significant effect on the individual’s career path.

Originality/value

While predicting the failure of healthy firms or the discovery of the main determinants that lead to such an event have received increasingly more attention in the last two decades, the focus on the consequences of BF is still lagging behind. The present study fills this gap by analyzing the aftermath of BF.

- Business failure

- Entrepreneurship

- Consequences

- Interpretative phenomenological analysis

- Learning from failure

Dias, A. and Teixeira, A.A.C. (2017), "The anatomy of business failure: A qualitative account of its implications for future business success", European Journal of Management and Business Economics , Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 2-20. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-07-2017-001

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2017, Artur Raimundo Dias and Aurora A.C. Teixeira

Published in the European Journal of Management and Business Economics . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

Business failure (BF) is a constant in today’s business world, being considered an essential and significant part of new business ventures ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Walsh and Cunningham, 2016 ). From the extant literature on the topic of the costs bared by the entrepreneurs, it is undeniable that BF is essentially a learning process ( Cope, 2011 ).

Although BF is hard to define, all definitions relate to the same significant event in the lives of organizations and individuals – the defining moment that unfolded over time where the survival of a company ends, creating losses for investors and creditors alike ( Jenkins and McKelvie, 2016 ). How that moment is determined varies widely among authors who have analyzed the phenomenon ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Khelil, 2016 ).

There is considerable debate regarding the narrative of the creation and performance of entrepreneurial efforts, but failure has received much less attention ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ; Shepherd et al. , 2015 ). The literature has thus far focused on predicting the failure of healthy firms, namely through prediction modeling using financial ratios (e.g. Altman, 1968 ; Zopounidis and Doumpos, 1999 ; Andreeva et al. , 2016 ); the discovery of the main determinants that lead to such an event ( Lane and Schary, 1991 ; Ooghe and De Prijcker, 2008 ; Ejrnaes and Hochguertel, 2013 ; Artinger and Powell, 2016 ); and the consequences that ensue from the failure ( Jenkins et al. , 2014 ; Mueller and Shepherd, 2016 ). While the first two research areas have received increasingly more attention in the last two decades, focus on the consequences is still lagging behind (see Amankwah-Amoah, 2015 ).

This paper aims to contribute to the scarce empirical research on the outcomes of BF for individuals (as emphasized in Ucbasaran et al. (2013) ). Many researchers highlight the need to analyze the aftermath of BF, specifically addressing: how the individual progresses and eventually develops new ventures ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ); how individuals change business behaviors and practices in light of a failure ( Cope, 2011 ); and what is the effect of previous failure on the individual’s future career path and/or decisions to embark on subsequent ventures ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ). The gap includes the learning process and all the actions and changes that are born from it. Questions like “How can these different outcomes be explained? What is it about certain individuals, BFs, and/or the nature of the stories that obstruct – rather than generate – action?” ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 , p. 197) are yet to be answered and require a better understanding.

The study thus intends to contribute to the empirical literature on the consequences of BF by developing insights into the consequences of BF and the reasons/conditions that enable entrepreneurs to succeed or otherwise hamper their success after a BF.

The pertinence of the study of failure is widely asserted, as are the benefits that emerge from such an experiences. The authors also believe that there is a key progression in time for the individuals, as successful business leaders are not born successful but rather fail continually until they achieve success – a concept that could prove useful to institutions and aspiring entrepreneurs.

To achieve this, we will focus on currently successful entrepreneurs who have failed in the past and try to understand the consequences of their past BF in the creation of new business ventures. Although many consider failure a pathway to success due to it being a learning experience ( Cope, 2011 ; Mueller and Shepherd, 2016 ), there is a lack of research dealing explicitly with prior failure as a condition for success or other considerations that reflect long-term orientations for the individual ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Singh et al. , 2015 ).

Qualitative research is key to understanding the “how” of the phenomenon, especially when trying to understand the development of the individual within his/her context ( Yin, 2009 ). Thus, personal accounts and narratives are essential to understand the process, although it has only recently been applied to this field ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ; Byrne and Shepherd, 2015 ; Singh et al. , 2015 ). Specifically, we will employ the Interpretative Phenomenological Approach ( Smith and Osborn, 2007 ), using a set of six selected case studies of entrepreneurs from several countries.

2. Research synthesis

2.1 defining bf.

BF is a not a simple concept to define ( Wennberg and DeTienne, 2014 ). Many authors (e.g. Deakin, 1972 ; Chen and Williams, 1999 ) do not feel the need to define the concept, while others (e.g. Dimitras et al. , 1996 ; Everett and Watson, 1998 ; Bell and Taylor, 2011 ), present a wide array of definitions in order to be as comprehensive as possible.

An analysis of 201 journal articles on the topic showed that besides the studies that do not provide an explicit definition of BF (about 70 percent of the total), [1] those that explicitly give a definition focus on one or several dimensions of BF, most notably: bankruptcy, business closure, ownership change, and failure to meet expectations.

This paper considers that BF occurs when a business closes, either for financially related reasons or willingly, which in the latter case can be due to the owners not achieving their expectations (e.g. not enough current return, no growth expectation, poor performance, etc.) in contrast to personal reasons (e.g. retirement, relocation, family issues, etc.).

2.2 On the consequences of BF

BF occurs over several distinct phases, usually contiguous to a significant event that is considered the tipping point of “failure.” The process includes the analysis of the conditions and series of events that lead to BF. It also considers the post-failure situation, focusing on the consequences of going through such a stressful situation.

The relevant literature can be categorized into three main research streams (see Pretorius, 2008 ; Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Amankwah-Amoah, 2015, 2016 ): BF prediction through modeling; determinants or causes of BF; and consequences of BF.

A brief bibliometric analysis of the documents published in journals indexed in the Web of Science (reference date: January 28, 2017), using as search keywords the combination of “business failure” or “start up failure” or “company bankruptcy,” limited to the field of Business Economics, resulted in 201 journal articles that focused on BF. More than one third of these studies analyze the determinants of failure (36 percent), with 31 percent trying to predict failure in organizations through mathematical models. The aftermath and outcomes of BF is only analyzed in 14 percent of the studies [2] .

To better understand the consequences of BF, researchers draw on many theories from the field of psychology, such as Attribution Theory ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ; Amankwah-Amoah, 2015 ) and grieving ( Bell and Taylor, 2011 ), in order to determine what each individual goes through when they experience a BF. Others look at specific conditions of BF that might affect the impact of the costs, such as applying the personal bankruptcy law in a given region and the asset protection it provides ( Hasan and Wang, 2008 ), and factors associated to Institutional Theory. Based on Ucbasaran et al. ’s (2013) work, it was possible to summarize the main theoretical contributions that frame this stream of research (see Table I ).

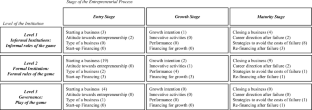

When widening the view, Figure 1 draws the theoretical framework for studying BF, in particular the consequences of BF. As illustrated, BF is a continuous process with key moments that require further study. The determinants of BF are intimately related with the consequences and the outcomes, as well as the psychological processes involved, and should not be separated from the individual, given the cognitive, behavioral and personality theories involved – all leading up to a key stage: rising from failure to achieve success.

Most of the studies analyzing the consequences of failure are focused on the individual. This may be justified by the fact that such individuals are either the survivors of the failure or the ones that support most of the consequences. In this vein, it comes as no surprise that most of the research done in this field is based on theories from psychology (e.g. Shepherd et al. , 2009 ; Yamakawa et al. , 2015 ). This specific literature stream usually considers failure a traumatic event ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2009 ; Byrne and Shepherd, 2015 ), where the individuals related with the failure gain a series of costs and benefits during the following period. Researchers feel that it is important to understand the different phases that one goes through after the trauma, which can resemble, in many ways, the death of a family member ( Bell and Taylor, 2011 ; Jenkins et al. , 2014 ).

Ucbasaran et al. (2013) divide the consequences of BF into three main timeframes: the Aftermath – the instant consequences that are supported after the event; Sense-making and the learning process – an evolving process that starts and takes place for an variable amount of time after the failure; and the Outcomes – the long-run outcomes for the individual affected by the experience.

In the first stage, Aftermath, Ucbasaran et al. (2013) refer essentially to the costs, which they basically classify as financial, social and psychological. The financial costs of failure may imply the loss of a main source of income, with the possibility of personal debt ( Cope, 2011 ; Bruton et al. , 2011 ). These costs might be increased or reduced by several factors, such as the entrepreneur’s current investment portfolio or the ease which they may have in obtaining new income sources ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ). Another factor is personal asset protection related to the bankruptcy laws that exist in some regions ( Eidenmüller and van Zwieten, 2015 ; Wakkee and Sleebos, 2015 ). As Hasan and Wang (2008) explain that exemptions might allow entrepreneurs to shield part of their assets, serving as a cushion for negative consequences.

When considering the social costs, they can understandably be devastating to the individual, both in personal and professional terms ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Nielsen and Sarasvathy (2016) . Drawing knowledge from Institutional Theory and Network Theory, the authors in this field argue that relationships suffer through this process, leading to stigma and negative discrimination toward future professional endeavors ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Simmons et al. , 2014 ; Nielsen and Sarasvathy, 2016 ). An example of a factor that increases the social cost of failure is given by Kirkwood (2007) , when he concludes that a culture with Tall Poppy Syndrome can be more unforgiving of high achievers who fail, pending on the perception of blame.

The media also often attributes BF to mistakes made by the managers (varying from region to region), being mostly linked to the impact and consequences the failure generates on its environment – all leading to a strong stigma ( Cardon et al. , 2011 ). Of the 389 failure accounts in Cardon et al. ’s (2011) data set, 331 contained statements on the impact of the failure being reported. The most frequently reported impact of failure (125 accounts, 38 percent) was the development of a sense of stigma around entrepreneurs who had experienced failure. One account stated that (see Cardon et al. , 2011 , p. 87) “Failure leads to exile and an abrupt end to one’s career path.”

Singh et al. (2015) view stigma as a process rather than a static label, considering that it occurs before and after the failure, arguing that it influences the failure itself and future endeavors. They also describe some situations where the stigma actually motivates the failed entrepreneur into starting a new venture, increasing the complexity of the social phenomenon.

The other costs considered in this framework are the psychological ones. These costs can be either motivational or emotional ( Shepherd et al. , 2009 ; Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ). Indeed, failure can be emotionally very stressing, creating negative emotions that are “inextricably linked to its complex social cost” ( Cope, 2011 , p. 611). Cope (2011) and Yamakawa et al. (2015) present empirical evidence where shame and embarrassment arise in failed entrepreneurs, derived from their strong commitment to the business stakeholders. These negative emotions often lead to withdrawal and, eventually, to loneliness, possibly impacting so strongly on the individual to the point of interfering “with the individual’s allocation of attention in the processing of information” (Shepherd, 2003, p. 320).

An example of an intensifier of psychological costs which is presented by Cannon and Edmondson (2001) is the individual’s own personal life experience and early socialization processes. The authors argue that parents often shield their siblings from harm while schools reward students who committed fewer mistakes, creating control-oriented behavior rather than learning-oriented behavior that leads to a significant decrease in self-esteem when focusing on one’s own failure. This ultimately leads people to engage in activities that improve their self-esteem rather than potentially damaging ones (i.e. to say, riskier situations of failure).

Motivation may also take a deep hit with failure, creating “a sense of helplessness, thus diminishing individuals’ beliefs in their ability to undertake specific tasks successfully in the future and leading to rumination that hinders task performance” ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 , p. 179). However, it may also serve as a boost for future endeavors as a compensation for missing a self-defined goal ( Cardon and McGrath, 1999 ; Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ).

Ucbasaran et al. (2010) conclude that both serial and portfolio entrepreneurs were less emotionally attached to their businesses, being less likely to have an adjusted optimism bias and having more resistance to psychological costs. Ucbasaran et al. (2013 , p. 180) also mention that entrepreneurs displaying “learned optimism” are prone to make sense of failure in a more beneficial way, motivating them to engage in future entrepreneurial activity and to see adversity as a challenge, for instance.

The sensemaking and learning dimension highlights the social-psychological process associated with failure, which might be framed by grief ( Bell and Taylor, 2011 ; Jenkins et al. , 2014 ) and attribution theory ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ; Yamakawa et al. , 2015 ), as well as the positive learning from experience ( Cope, 2011 ; Singh et al. , 2015 ).

An important article to consider here is that of Mantere et al. ’s (2013) on narrative attributions of BF, where the authors attempt to reconstruct and define the determinants of failure through the attributions of different point of views related to a single situation, thus analyzing how the individuals make sense of reality. Through an inductive analysis, the study categorizes seven distinct categories of attributions: catharsis, hubris, betrayal, mechanistic, zeitgeist, nemesis and fate. The authors ultimately relate these attributions with the sensemaking and recovery process, concluding how they are “driven by the cognitive and emotional needs of organizational stakeholders to maintain positive self-esteem and recover from the loss of the venture” ( Mantere et al. , 2013 , p. 470).

As Shepherd (2003) highlights, the experiential nature of learning from one’s mistakes is also present in owners of businesses that failed, prompting a revision on the individual’s knowledge of how to manage their own business effectively. However, the author also clearly establishes that failure induces a process of grief, creating an obstacle to learning from the event experienced (Shepherd, 2003). This is allied with the need to make sense of the situation, as it is “an interpretive process [that] requires people to assign meaning to occurrences […] and involves ongoing interpretations in conjunction with action […]. It [sensemaking] involves both the cognitive and emotional aspects of the human experience” ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 , p. 184).

Interestingly enough, Yamakawa and Cardon (2015) find evidence that entrepreneurs that focus on their role in the failure are most likely to learn more from their experience than individuals that focus on external influences.

The last dimension is related to the long-term Outcomes for the individual due to the experience he/she had with the failure, its costs and how he/she made sense of them ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Mueller and Shepherd, 2016 ). This includes how much the individual learned and how the individual changed their business practices. As Cope (2011) argues, the importance of failure lies in all the changes that follow from it, where the individual reviews a set of ways and might even create longer-term positive consequences.

Deriving from cognitive and behavioral theories, Politis and Gabrielsson (2009) conclude in their work that experience with business closure is associated with more positive attitudes toward failure. Basing on the Experiential Learning Theory, the authors argue that “experience from closing down a business seems to lead to a more positive attitude toward failure by rendering existing behaviors and routines inadequate, which in turn can trigger change in underlying values and assumptions” ( Politis and Gabrielsson, 2009 , p. 376).

Cardon et al. (2011) and Rider and Negro (2015) further explore the impact of failure on the future career path of entrepreneurs, finding that some prefer to continue to engage in entrepreneurial activities while others opt for jobs in more established companies.

3. Methodology

The method of qualitative research employed in this study consists of a set of case studies, using the methodology design advanced by Yin (2009) , based on a collection of personal accounts from individuals that meet pre-defined criteria through face-to-face interviews, using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) ( Smith and Osborn, 2007 ). The IPA approach has been used before in the research on “BF Consequences” ( Cope, 2011 ) and enables an introspective view of experiencing failure. Cope’s (2011 , p. 608) use of interpretative phenomenological research is justified with “the strength of a qualitative research design such as this lies in its capacity to provide situated insights, rich details and thick descriptions. Richness is provided by paying close attention to both context and process […].” This methodology allows the researcher to empirically achieve a better understanding of the emotional consequences of failure and its relation with the learning process.

For the purposes of this study, the main advantage of this methodological approach lies in the possibility of thoroughly investigating an individual and his/her progression over time, within a real-life context ( Yin, 2009 ) – which, as we have determined from the framework (cf. Figure 1 ), is fundamental for the appropriate analysis of the experience.

The analysis will start with an account of the BF process, trying to extrapolate what the individual considered were the determinants of the failure. The research should therefore include a full overview of the BF. The analysis will then focus on understanding the impact of the aftermath, in terms of the financial, social and emotional costs ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ; Singh et al. , 2015 ; Nielsen and Sarasvathy, 2016 ). This includes not only identifying the moderators of the cost, but also an effort to identify how the individual managed to overcome those costs, acting on the assumption that they are closely related to the learning process ( Cope, 2011 ; Yamakawa and Cardon, 2015 ; Mueller and Shepherd, 2016 ). Since this is reported through a personal account, it is also part of the sensemaking process ( Cope, 2011 ; Yamakawa et al. , 2015 ). In a following stage, we will focus on the sensemaking process, learning process and the outcomes of the individual.

Particular attention should be paid to the psychological processes that influence learning, such as grieving ( Cope, 2011 ; Jenkins et al. , 2014 ), narrative attribution ( Mantere et al. , 2013 ; Amankwah-Amoah, 2015 ), and loss of orientation strategy (Shepherd, 2003).

Figure 2 summarizes the main steps and the guideline research questions of the empirical work.

The individual must be an entrepreneur, being directly involved in the creation of both the failed and the successful business;

part of the venture’s founding process;

CEO or other high management level position; and

personal or family-related ownership stakes in the venture.

there must have been significant losses associated with the failure (e.g. initial round funding, years of dedication); and

the reason for closure must not be personal (e.g. retirement, as mentioned by Watson and Everett, 1996 ).

The successful business should have a significant commercial success with a considerable profit rate, solid enough to support the founders or show sufficient recognized potential growth.

For this study, and in line with other qualitative studies in the area (e.g. Cope, 2011 ; Pal et al. , 2011 ; Singh et al. , 2015 ), the cases selected were purposive by nature, meaning that any individual that filled the pre-requisites would be of significance for the research project. An effort was made to not contain the search within a single country, in particular the concentration within a single region in Europe, although admittedly being difficulty due to the selection criteria defined and the very own personal nature that study subject demands.

To obtain these case studies, extensive contacts with potential candidates were made through personal networks, social networks, references and internet research. In total, the research was advertised through several European social networks of entrepreneurs, 12 personal reference requests plus 2 academic research reference requests. This initial effort resulted in 19 potential case studies (from a variety of countries, namely Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Portugal, Spain, and The Netherlands), of which 13 contacts were followed through. Of these 13 contacts, four did not respond and three failed to pass the pre-verification phase. The final result yields the six case studies presented in Section 4 , composed of individuals that generously agreed to participate in this study.

Six data collection interviews were conducted with successful entrepreneurs from two main regions in Europe, specifically the Nordic region (with Finnish and Danish representatives) and the South of Europe (with Portuguese representatives) (see Table II ). Although two studies on the consequences of BF already focused on individuals located in Nordic countries, most notably Denmark ( Nielsen and Sarasvathy, 2016 ) and Sweden ( Jenkins et al. , 2014 ), no study has yet analyzed individuals from the South European countries, less so in comparison with their Nordic counterparts. Such comparison is potentially very interesting as these two regions contrast significantly in terms of culture, particularly in terms of uncertainty avoidance and indulgence ( Hofstede and McCrae, 2004 ), two traits significantly associated with entrepreneurial behaviors and attitudes ( Mueller and Thomas, 2001 ). Though from the South of Europe we only have Portuguese representatives, according to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions Portugal and the other Southern European countries (Italy, Greece, and Spain) share common traits. These countries are characterized by very high uncertainty avoidance and very low indulgence, which means that in these cultures innovation may be resisted, security is an important element in individual motivation, and there is a tendency toward pessimism. In contrast, Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) citizens do not need a lot of structure and predictability in their work life and evidence a tendency toward optimism (see https://geert-hofstede.com/ ).

As can be observed in Table II , the Nordic representatives are younger (26 years old, on average) than their Portuguese counterparts (44 years old, on average), presenting lower levels of formal education (at most they have a bachelor degree, whereas the Portuguese entrepreneurs have master degrees or MBA). Regarding the business areas of the ventures that have failed, they were diverse, including manufacturing (food cutlery, medical/cosmetics), and low (food and leisure) and high knowledge intensive (sound and automation engineering) services. When disclosed, the amount of financial investment in the failed venture was relatively low (between 7 and 300 thousand euros). The failed ventures were, on average, six years in operation, with the time invested in the business being higher for the Portuguese (seven years, on average) in comparison to the Nordic (four years, on average) entrepreneurs. All the new entrepreneurial ventures operate in a distinct business area of the failed venture. They seem to be rather successful, with more than five years in business (at the time of the interview), entailing a considerable investment (Cases 4 and 6) or yielding relatively large revenues (Cases 1-3).

After an initial contact and agreement to participate in the study, a pre-screening meeting with the selected entrepreneurs was scheduled, followed by the data-gathering interview where additional information was required to prepare the interview script. The semi-structured interviews, which had specific questions prepared in scope of the proposed research framework, took place during the months of February, March, May and June 2014 in various physical locations, such as company headquarters and college campuses, but also via Skype. They were recorded, transcribed and analyzed through the IPA methodology and the predefined framework in Figure 2 during the months of April and June 2014.

4.1 How the individual progresses and eventually develops new ventures

The first aspect considered was what follows a BF, in particular how the individual progresses and eventually develops a new venture. Related to this topic, a cost-benefit trade-off analysis seems relevant.

The benefits seem to be truly significant for the individuals, even when costs are not. The individuals also naturally tend to focus on the benefits, telling the lessons learned when they were asked for the narrative – particularly visible with Brian, André and Marius. Furthermore, there are key events that can be directly related to the creation of the future successful business – Brian met one the future business partners who had acted as a mentor of his failed project, Paulo decided to go back to college only to find the next business idea, and Marius kept the same partner in all of the started 4 companies. Business connections are known to be synergic, thus it is no surprising to find that the effect continues even when amidst failure.

It is worth noting that some of the successful projects were already being started while the failures were taking place, most specifically at the end. Mikko was already quite involved in the first steps of the subsequent successful business when before the sale of the failing family business; and Marius was preparing a crowdfunding campaign when the first company closed.

Another dimension to consider after the failure is how the individuals deal with the costs. As previously discussed, none of the cases present overwhelming financial losses, meaning that the individuals required minimal effort in order to overcome them. This was mainly attributed to institutions that served as moderators (e.g. governments, family). The reduced financial costs generated relatively minor social and psychological repercussions ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ).

Still, a few actions taken to restore normality to the individuals’ lives are discernable. Paulo admitted to cutting back on the family budget, taking fewer vacations, along with also going back to college – an action that could surely be connected to a sensemaking process. Actions during the failure are also visible, very likely an anticipatory sign of grief ( Shepherd et al. , 2009 ). These actions are visible in the projects that are described as “fading,” for instance, when André claimed that the focus shifted back on the full-time day job or when Marius admits to have focused on creating new businesses rather than just investing in one.

Focusing on the psychological costs, they were visible for some of the younger entrepreneurs but the serial experienced entrepreneurs appeared minimally affected. Mikko and Brian admitted to have suffered a significant amount of stress, while Marius felt that it would have been much worse with the absence of the previously created successful ventures by the time the first one failed. Paulo reduced the costs to a “post-failure depression” to a 24-hour period, while José merely admitted to some frustration for nearing loss immunization. André rationalized the failure as a calculated risk and is proud of it for being a rich experience. The fact that both André and Marius’s project faded away could be pivotal for their emotional reaction, in particular in the case of Marius, admitting some attachment to the failed company.

It is also arguable how opportunity costs are smaller when the entrepreneur is younger. Paulo’s narrative focused much more on the family responsibility, while Marius’ focus was on where the nature of such a professional life would take.

It is also very easy to identify the benefit of certain skills gained during the BF. For example, Marius admitted to the usefulness of learning how to set up a company in the first business while Mikko valued the knowledge of how to manage a financial budget. These skills seem to be more prevalent in younger individuals, as would be expected, since they have much more to learn. André recognized this, stating that the professional experience stemming from entrepreneurial business or established business is similar, only the risk involved changes.

Similarly to the costs/learning relationship, a small-scale business investment does not necessarily mean that it does not yield important lessons for the individual. Brian claimed learning a lot in terms of working with teams, considering that it was good that it happened with an investment of €7,000 rather than a much higher amount. This also includes time investment, with Marius and André both admitting to have gained a great deal from a relatively small investment of time when compared to their other projects.

Actually, when we said to each other “Hey, okay, it’s over […]”[…] it was a big relief. It was like taking the biggest backpack off your shoulders […] it was a really great feeling, I can so easily remember where we were sitting, what the weather was like and the feeling in my body. It was a crazy feeling, only kind of positive somehow.

Such a detailed description is revealing of the importance of the event and the backpack actually illustrates perfectly the figurative burden off the shoulders.

It is interesting to see other individuals that were not as lucky to have those types of moments, where the connection was simply cut off. Paulo was still in legal court battles at the time of the interview, a decade after the BF. It was clear the whole tiredness of dealing with the issue. José also stressed a failed expectation to shut down the eventually failed venture much faster than it actually happened, admitting that the goal was to be as fast as possible in order to cut losses, unattainable due to facing a lot of slow-moving stakeholders that delayed the process several months.

Of course, the situations illustrated here do not have significant follow-up costs, like many entrepreneurs with personal debt issues and the lack of a source of income. Still, it might be relevant in removing the uncertainty that is so stressful for many.

The likelihood and profitability of progressing toward a new business are increased when (a) individuals perceive positive learning benefits from the BF (b) individuals share meaningful/useful business connections and/or support from science and technology infrastructures (c) failed projects did not present substantial personal financial loss and (d) there are moderate factors, such as the support of formal (government) and informal (e.g. family) institutions, that curb the perceived costs involved in the BF.

Age impacts significantly on the perceived psychological costs of BF.

Age moderates the effects of learning benefits perceived from BF.

4.2 How individuals change business behaviors and practices in light of a failure event

In business, learning usually means a change in “how things are done.” In the case of the defined framework, these changes are usually most visible in the longer-term outcomes.

In terms of cognitive changes, the existing literature focuses on optimism ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ), an aspect this study does not specifically address. Instead, it focuses on other cognitive changes, especially on the perception the individuals have of themselves, entrepreneurship and other life-related topics that were brought up in the non-rigidity nature of the interviews. The behavioral literature focuses on the intention of continuing to launch ventures (which was a pre-requisite for this study) and changes/improvements in business practices, which is also addressed in the course of this study.

In light of this, several key points were identified that could support the current literature, add other relevant information and indicate further paths to better understand the phenomenon.

The main question lies is in what way do the individuals change their business behaviors and practices in light of a previous failure event – a process that turned out to be easily observable with clear links between the two different experiences.

For instance, and as previously discussed, it is easy to associate Paulo’s values and the measures implemented by the entrepreneur of the successful company with the betrayal previously experienced by the failure. One could identify that it does relate these with these aspects on some levels, such as in the attention paid to drawing up much more tightly written contract with the owners of his business to avoid litigation and ill intentions. Brian also claimed some business practices changes, specifically regarding team picks, much as André said that on the following projects, the partners were chosen in a very different way from the previous project.

Marius also learned cognitive changes that shaped his behavior, by discovering that, in this particular case, the motivation was affected by what was daily developed, asserting that it was not enjoyable to just focusing on developing a product without having business tasks, a feature that drove Marius to start new businesses. However, the narrative progressed to another important behavior change, where it’s decided that one could not be running multiple successful businesses and a much needed focus in order to produce better results, culminating in the closure of two projects and the launch of the latter most successful one.

A specific type of behavior worth analyzing is the individual’s actions with regard to risk after failure. While it is evident that these cases present a somewhat biased analysis for this factor, it seems clear that the individuals maintained the same attitudes toward prospecting and assessing new market opportunities. Even though they failed, they kept trying, with many reporting an increase in confidence. André, Brian and Marius also admitted that they have invested more of themselves and taken more risk in the projects, claiming to value more attitudes such as a “commitment,” “focus” and “100% in” within their projects.

Of course, these behavioral changes are also accompanied by significant cognitive change. As stated, confidence and self-awareness of their skill was repeatedly brought up by the interviewees. Brian and Mikko also said that knowing they can survive failure is important, most certainly increasing their resilience. This might indeed support Shepherd’s (2003) conclusion that being aware of these normal negative emotions resulting from failure can in fact reduce the stress associated with it.

André was proud of the failure and Marius called it a unique learning experience. This outlook is mostly highlighted by the younger individuals, whereas the older entrepreneurs tend to focus much less on this dimension, although some changes in their behavior are still visible (perhaps to lesser degree), as previously discussed. For instance, Paulo decided to no longer work for the Portuguese market and ended up with a Portugal-based international company without a single Portuguese client; and José admitted to have never used venture capital money again, stating that forward such financing would be raised in a much more careful way.

BF tends to entail changes in subsequent business behaviors and practices (e.g. legal procedures/contracts; choices of the management team; choices of the funding partners/sources; strategic business focus).

4.3 The effect of previous failure on the individual’s future career path and/or decisions to embark on subsequent ventures

Regarding the effect that the failure has on the future path of the individuals, it is safe to say that it had a significant impact. The literature usually refers to changes in career path as a coping mechanism to overcome financial costs ( Ucbasaran et al. , 2013 ). Ucbasaran et al. ’s (2013) study, however, does not have such a narrow view of career change (although one of the individuals admitted this applied in his case). It tries to identify smaller shifts in the entrepreneur’s progression, such as changing industries, changing roles and even investing in further education to achieve a different career path.

First and foremost, it should be noted that these cases present a biased view of how the careers may possibly progress – after all, by design, these are considered people who followed and became successful entrepreneurs.

But even within the entrepreneurial culture, differences and deviations can be found between success and failure. For instance, Paulo shifted from a low-tech venture to a full-fledged tech start-up, focusing mostly on research and development. This was fully intentional, as it was one of the reasons why Paulo went back to college, to afterwards engage in such a project with expectations of entering the international market.

In truth, all the interviewees changed their industry when they started new projects. Mikko shifted from food services to event management and Brian focused on entrepreneurship education. André preferred to stay on the path of corporate job career and invested in the IT retail market, re-applying the knowledge previously gained, taking advantage of opportunities detected previously and compensating for the costs of the failed venture. José also showed no indication of continuing to invest in projects within the music equipment industry, admitting that it was an extremely difficult industry to enter.

Marius presented an even clearer picture, by claiming that the failure was a help in deciding what professional career to choose. The failed business was in medical/cosmetic products and the successful one in pure consumer electronics, but they do however share key traits – they both focus on a physical product with global potential. Marius adds that it is exactly what he wants to do with his career, acknowledging that the latter successful investment was identified and pursued based on the knowledge gained with other businesses and the failed venture.

BF is likely to significantly impact on individuals’ future career path.

Subsequent business ventures tend to operate in distinct business areas of the former failed ventures.

Subsequent business ventures tend to require new knowledge and/or the application of entrepreneurs’ accumulated knowledge to new areas.

4.4 How can these different outcomes be explained? What is it about certain individuals, BFs, and/or the nature of the stories that obstruct – rather than generate – action?

An entrepreneur’s lifestyle is often considered a continuous iterative process. André appears to share this vision, when claiming that individuals that share these kinds of traits will try again until they are successful – only to later distance themselves and support new projects, by developing or investing in them. This progress is not always continuous.

Considering this sample, many individuals had to launch several projects until they achieved a desirable level of success. Marius owned three companies at a point, until identifying his current venture, deciding to separate from all other projects and focus on the one that foresaw the highest return. Paulo, after having businesses in the IT industry, real estate industry and leisure industry, decided to put his professional activity on hold to return to college in order to be able to start a different kind of company. Another example of how this progression is somewhat chaotic is the case of Mikko, who was already involved in his next project while still tied to the failing venture. André kept working for the IT company for years while gathering the required resources to launch his technological start-up.

Context seems to influence the actions and decisions of the individuals in the short term, but a wider view shows that success can be achieved in spite of unfavorable environments, as it appears to stem from the nature of these remarkable individuals. These individuals found success most likely due to the characteristics they possess, such as resilience, favorable personal background to overcome the costs and, perhaps, a bit of luck.

The individuals’ cognitive traits and the changes they experience could also prove to be pivotal for the future outcomes. A good example is when Paulo firmly states that managing a business is key driver, along with wanting to lead and to be the boss. Paulo shows great self-awareness when admitting to be stimulated by unstable environments – a contrast with André’s case, which seems to be very risk averse but, nevertheless, manages to plan a career in accordance in order to avoid high exposure to the risk of failure.

Another important phenomenon occurs when Marius distances himself from the failure. Dwelling on the fact that of previously creating two other relatively successful companies when the first one was nearly shutting down, admitting that had the focus been put exclusively on the one company that failed it would have been a “more personal failure.” Marius talks later about being unsure of he would have invested in the last and more successful business if the previous had not occur – specifically, if the chance of learning “what to do and what not to do,” the chance of trying different things and projects, or even if the focus had only been set on one project, concluding that actually would never have met his current partners of the successful business.

Still on the issue of factors that can generate or prevent action, a common important narrative point is related to how the business venture ends. The interviewees seem to value a decisive and fast closure, as the source of stress seems to derive more from “failing” than from the actual “failure.” The contrast is also visible in cases that dragged out over time and passed from stakeholder to stakeholder, battling in procedural and legal disputes.

Even if the individual wishes to try again or keep the venture going (as previously mentioned, a possible method of anticipatory grief; Shepherd et al. , 2009 ), when the time comes to inevitably shut the business down, there is evidence that the faster it happens the better it is for the individual to move on – much like removing a bandage quickly.

Subsequent business success encompasses business intermittence and several past BFs.

Fast closure of the failed venture is likely to push entrepreneurs to subsequent new business creation.

5. Conclusions

5.1 main contributions of the study.

The evidence gathered shows that previous failure impacts on individuals strongly. Such an impact appears to be conditioned by the individuals’ experience and age, and their own perception of blame within the failure. However, for these particular individuals, it does not appear to be affected by the size of the project or the amount of financial loss.

Moreover, certain antecedents, specifically, the involvement of institutions in the individuals’ lives, can significantly curb the costs suffered after the failure. Some case studies reported a feeling of relief when the failed business closed. It is possible that a quick cease of contact with the failure may be beneficial, in contrast to the case that endured long legal battles.

It was also found that all the individuals’ career paths were influenced by the failure, with some having a much more significant impact than others. Failure or failing were a pivotal moment in the lives of the participants in this study – some individuals were even already developing or had already developed their next full-time project while the failure occurred, having immediately changed focus afterwards.

5.2 Implications of this research on theory and practice

Theoretical and practical implications can be drawn from these conclusions. For young and aspiring entrepreneurs, their future ventures should be seen first as a learning experience and should be prepared with serious consideration for failure. They should adapt their expectations to the fact that, in case of failure, it is not a lifetime ban on success. It is possible to bounce back and the lessons that they acquired during the failure may prove very significant in the future. Evidence was also found on the development of key cognitive and behavioral changes that the individuals directly relate to the failure and are considered crucial for their current success. Other key aspects that influence success were identified from the previous failure, like meeting a future business partner or connection during the process.

With regard to the implications for institutions, cases have been described where entities restricted or inflated the aftermath costs. In the case of NGO and education professionals, failing to maintain a business venture is still a very significant learning experience, especially at a young age. In these cases, three individuals participated in such programs and two launched businesses within a prepared risk-controlled framework, later growing out of it. Thus, preparation of a controlled environment for failure appears to produce truly interesting results. Bolinger and Brown (2015) make a similar case when claiming that entrepreneurship education should take a role in focusing the positive consequences of failure.

Regarding public institutions, there were positive aspects produced with the reduced risk funding programs that some individuals opted for. These benefits appear to have been mostly at the level of the individuals that owned the business. Cost enhancers were also visible, specifically with the complications that some individuals faced in closing their venture. Long legal battles were the main reason for this, and should be considered very detrimental for entrepreneurial development within a country.

5.3 Limitations of this research

This research focuses on the personal point of view of the subjects, which for most of them occur in a point of time after a certain kind of redemption has been achieved from their past failed projects. This view is somewhat reductive of the full scope of the phenomenon, not capturing the advent of the failure, the immediate following period nor the atonement achieved later on.

Additionally, it should be noted that this study only focuses on individuals that successfully tried again to launch a business of their own after having failed previously. However, insufficient evidence can support or steer future research on a path to better identifying the factors that hinder or foster action toward future entrepreneurial efforts, either based on individual actions or originated from the context. For example, as discussed in the section on financial cost moderators, all the cases had significant help from others or other sources of income that shielded them from more damaging costs. This could certainly be an important factor for their careers. It is also a rather poorly research topic, since most of the institutional theory in BF research focuses on bankruptcy law – the government, however, is not the only institution that affects the lives of the entrepreneurs.

5.4 Future research recommendations

Implications for the further development of this field are mostly related with the need for further empirical evidence (both quantitative and qualitative). This study focuses on individuals that failed and then found success in entrepreneurial ventures – there is still a wide array of longer-term outcomes (or stages in life that can be considered different outcomes) that need to be analyzed, as they can produce very interesting results.

Relating to each of the stated conclusions, one could draw on the observations and potentially identify many research opportunities for the future. For instance, one could learn more from the entrepreneurs’ personal and professional development if analyzed through a longer period of years and in different contexts and stages of his/her life. The identified key events of their lives, social developments, specific skills and learning points, and perhaps even personal and financial cost bearings would most likely be identifiable in a quantitative research initiative, perhaps providing a much clearer insight.

A much wider sample might also allow a deeper understanding of the conclusion present in Section 5.2, as the research project is only designed to analyze one specific outcome after a BF. For example, the analyzed set of individuals kept the same attitude toward new business ventures and potentially risk assessment – one could argue that it might not always be the case after a traumatic experience. It also relates to the point stressed in Section 5.3 – the changes on one’s persona potentially led to a specific outcome, a future career that involved another business venture. It would also be interesting to see how these changes are perceived by a larger target – would the eventual success be attributable to the previous traumatic experience? Would the weight of the costs be worthy? Relating to Section 5.4, and perhaps even more interestingly, would failure be a significant variable in the explaining of eventual success? In a quantitative research, it would be difficult to perceive certain decisions in a timeline, but some clear key event would still be identifiable – business creation and business closure, cost moderators and investment risks. Correlation between events and outcomes could guide research to a better understanding of the phenomena.

Finally, evidence was found of significant factors and patterns within the cases that deserve a more in-depth and qualitative analysis. For instance, younger individuals showed a much more emotional response to the phenomenon, also reporting much deeper lessons. In contrast, senior individuals showed lower psychological costs. Similar to other studies, context is still very present within the narratives of the entrepreneurs, as are the antecedents of the failure – although it is not a focus of this study, several relationships were established between previous facts of the failure, expectations of the venture, and the process of failure itself with the aftermath costs endured by the individuals and the sensemaking process.

The resilience shown by the “serial entrepreneurs” analyzed lets them endure cost after cost, feeding their drive even when they actually achieve success. These individuals deserve a study dedicated only to them.