College Essays and Trauma: Students Are Being Pushed to Write About Their Worst Experiences

Last spring, I interviewed for a job providing essay support with a company that works with high schoolers on their college applications. Services like this are expensive: According to a 2019 article in US News , comprehensive college consulting packages can range from $850 to $10,000. Because of the price point, these services are often reserved for students from economically privileged backgrounds. “These students are really at a disadvantage these days,” my interviewer confided. “What would you tell students who haven’t experienced trauma when working on their essays?”

I was immediately struck by the linking of privilege with disadvantage. I was uncomfortable with the one-for-one association of income bracket and adversity as if having money protected high schoolers from anything bad ever happening to them and that coming from a lower-income family automatically meant students were traumatized. Most of all, I was shocked by the emphasis being placed on trauma in college application counseling.

Trauma should not be a deciding factor in college admissions. Students should not need traumatic experiences in their past in order to be competitive applicants, nor should they feel forced to disclose anything that they may have gone through. Pain should not be the avenue through which students must represent themselves. And students who do not feel they have experienced much adversity or hardship should be grateful, not bitter, and write about any of the other things that make them who they are. But as the volume of applications that students send out continues to rise , applicants are desperate to stand out.

What do colleges actually hope to learn about a student through their essay? According to the CollegeBoard , they want “a unique perspective, strong writing, and an authentic voice.” Harvard Business Review says the Common App essay is “your chance to show schools who you are, what makes you tick, and why you stand out from the crowd.”

At its best, the college application is an opportunity for a student to go from being a set of data points to a human being. The essay can demonstrate a student’s writing ability, style, and flair. It can prompt a teenager to reflect on their values, on the moments and experiences in their lives that have shaped them, and on their understanding of their own selves. I am, primarily, a personal essayist. I believe deeply in the power of an essay to function as art and to reflect something much bigger than ourselves. I could even be convinced that a 650-word limit might be a productive constraint in essay writing. The personal essay could be good for students if students actually felt any topic was available to them, if they felt they really could write about their passion for pickleball or fan fiction instead of thinking that milking adversity could equal bonus points in their application file.

At its worst, college essays force high school students to search through their personal experiences for a trauma they think they can sell. Meanwhile, as former foster youth Emi Nietfeld wrote in Teen Vogue , young people who have faced immense adversity struggle to capture their experiences neatly in a few hundred words. When students compare themselves to their classmates, especially when applying for the kinds of colleges and universities that take a limited number of students from a specific high school, they are practicing ranking themselves against their peers in a form of trauma Olympics. They are not learning to be empathetic to the people around them or to recognize that they can never know the entirety of what people are carrying with them.

The Supreme Court's decision to overturn race-based affirmative action puts an even harsher burden on applicants' essays. Colleges can’t consider the systems of inequity that may affect students of color, but individual students can include their experience as a marginalized person in the essay . Many college admissions boards are still mostly white , and students of color may have to find ways to communicate their identity while also answering the essay prompts. This narrows what applicants think is worth writing about or what makes them worth receiving the education they dream of.

This summer I worked with a group of 16- to 18-year-olds in a creative writing class. For many of them, it was their first experience in a class like this. One afternoon, a student started writing about something they hadn’t thought about in years and ended up in tears over their laptop. We built a space where these students felt safe and supported to explore their trauma in writing and it often came out in incredibly moving 10- or 15-page essays. The projects were open-ended, so the story they needed to tell dictated how long the piece would be. Our students didn’t need to pretend their experiences had a neat conclusion. They could be honest. They could reflect and process, and then they could share a piece of writing with a community that cared about them.

The college essay allows for none of this when students feel required to write about adversity. Some students have already asked for a kinder application process , citing the damage the process as a whole does to their mental health. If students have trauma they need to work through, and if writing can help them do so, they should have space to safely, deeply, and thoroughly write about what they need to say without turning it into a self-sales pitch. The college essay should be a space for exploration and reflection where students can present what they care about and what makes them who they are.

Stay up-to-date with the politics team. Sign up for the Teen Vogue Take

Check out more Teen Vogue education coverage:

Affirmative Action Benefits White Women Most

How Our Obsession With Trauma Took Over College Essays

So Many People With Student Debt Never Graduated College

The Modern American University Is a Right-Wing Institution

What It’s Like to Be Sued As a Student Journalist

Dumping Your Heart Out: “Trauma Dumping” in College Application Essays

Exploring the advantages and pitfalls of writing the common application personal statement about traumatic experiences., reading time: 8 minute s, by ayesha talukder , sophie zhou, issue 1 , volume 114.

Summer: a time of abundant sunshine, ice cream, and … college applications. Rising seniors pass the days constructing school lists, applying to scholarships, and studying to take the SAT one last time. However, there’s one part of the college application process that’s particularly stressful: essays. The number of essays a student will write will vary based on which schools one is applying to, but it’s common to write up to 20 essays . Arguably the best-known essay that students write is the personal statement, which is submitted through the Common Application portal. This portal is used by over 900 colleges and universities and has seven prompts that students can choose from, each of them meant to bring out a side of the applicant not showcased in other parts of their application.

One approach to writing the Common App essay has been dubbed “trauma dumping,” where students center their essay on personal traumatic events. This term has since evolved to include essays focused on any intense hardships that the student experienced (whether they resulted in psychological trauma or not), otherwise known as “sob stories.” For the purposes of this article, “trauma” will be used to refer to any hardship that had a long-lasting impact on the student. This essay-writing approach has been popularized by viral social media stories, where trauma essays are portrayed as the “make-or-break” factor in college applications; a well-known example is Abigail Mack, who went viral on TikTok after sharing her “ letter-S” essay about the loss of a parent. Mack was accepted to Harvard University.

Some students feel pressure to use trauma in their essays to make them stand out. Maggie Huang (‘23) is currently majoring in pharmacy at St. John’s University. “I think a lot of people treat [the college essay] as a major important thing in their life, like they have to sell themselves really badly and be like ‘I went through so much, I deserve to be here.’ [...] You're only 17, 18, so there’s not that much else you can talk about unless you did something really, really revolutionary,” Huang said. The pressure to stand out can be especially intense at a school like Stuyvesant, where there are countless high achievers and accomplished students. “When you hear about all the things your friends [...] are doing, [your own accomplishments] don’t seem impressive enough. I [felt] really very painfully average when compared to the rest of Stuy,” Huang added.

By the time college application season arrives, essays are often viewed as the only thing on a student’s application that they still have control over. “Your grades are already your grades, your SATs are already your SATs, you’ve joined whatever clubs and pubs you’re going to join, so [the essay] feels like the last chance, the last thing that’s still up for grabs,” Assistant Principal of English Eric Grossman said. Because of this, students often feel pressured to make up for the weaker points in their application by crafting a powerful essay.

Thus, trauma often becomes tempting as a way to stand out. “A lot of Stuy kids are immigrants, first generation, etc… or have had something bad happen (I mean, COVID was literally handed on a silver platter to us). Maybe it’s just me, but it feels easier to just write about that because it’s so much easier to make yourself seem inspirational and deserving of being in a school for having made it through that kind of experience,” Huang said.

English teacher Mark Henderson agreed that including trauma in an essay is often presented as a means of earning a spot at a prestigious institution. “The whole college application process is really unfair to students and that aspect of it feels really gross to me. Students feel as though they are being asked to share things that are really hard to share with strangers in order to like, you know, win something—basically to win an acceptance to a college and all of that,” Henderson said.

However, others, such as Bill Ni (‘19), a graduate from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute and current software engineer at Amazon, believe that there isn’t any pressure to include trauma in college essays. “I don’t think there’s any pressure to use trauma … [However,] I still feel that it’s presented as an option, but it’s not something you have to, like, 100 percent use.”

Ultimately, though, deciding whether to write a “trauma essay” should come down to the student’s own level of comfort with revealing a vulnerable experience in their life. This can be more difficult than students may initially assume. “If you’re writing about something traumatic in your past, exploring that topic in a piece can be traumatic in itself because you may, depending on what it is, be reliving it,” Ni said.

Ingenious Prep Associate Director of Counselor Enrollment and Communications Zak Harris agrees that it is crucial for students to think carefully about whether they are fully prepared to share their trauma. “If you’re going to go down this path, you have to be 110 percent behind yourself to some degree,” Harris said. Thus, it may be easier for students who have already worked through their trauma to mention it in their essays: “With students who are doing clubs and organizations, volunteering, [or] working for a nonprofit that connects to some of the issues that they’ve had, I think that’s where it’s a little bit different, because their day-to-day experience is sort of using that trauma [...] So that might be a little bit better than someone who is, I think, still navigating and figuring it out,” Harris added.

Students should be aware that “trauma essays” can be controversial and aren’t well received by everyone. Some people caution against them because “trauma essays” can become too focused on the traumatic event itself and not on the student’s cultivated strengths. At Stuyvesant, senior English teachers dedicate an entire unit to helping students with their college application essays, often providing individualized feedback. “[My English teacher] said actively to avoid trauma dumping, because it’s so overdone and it doesn’t tell the college anything about you specifically,” Huang said. After hearing this advice, Huang switched gears with her essay. “Originally, it was about like a family situation and then it pivoted to my acceptance of my identity of being Asian-American in America, which is still kind of not completely trauma-free, but at least it wasn’t as bad as before,” Huang said.

Additionally, there is also the risk of admissions officers having biases against certain traumas, especially those relating to mental illness. “There are many colleges that have lawsuits going on against them right now connected to mental health issues and their slow reactivity to things that current students have been going through,” Harris noted. “Sometimes what happens in admissions is that if there's any risk, then I think there's going to be a pocket of people that will say, ‘Well, don't do it, because it's risky.’” However, this is slowly changing as mental health issues become more openly discussed and the stigma around them decreases. “I think we are in a generation and a time where mental health struggles and issues are widely talked about in a way that 10, 15, 20 years ago, they were not talked about as much, which I think actually is helping admissions officers become more comfortable or even more open to reading about these things in essays,” Harris added.

One way students can communicate relevant traumas to admissions officers outside of their essays is to ask their recommenders to include that information in their letters. “It's quite often, I find, when I'm writing recommendations, that [the letters] could be a really useful place for somebody else to sort of explain and put [traumatic events] into context, in the context of recommending them,” Henderson suggested.

If a student does decide that they want to write about trauma in their essay, they should be cautious of how they frame it. Students should make it clear that their goal is not to seek sympathy from the admissions officer, but to demonstrate how they’ve grown from their trauma. “The admissions officer [shouldn’t be] just focusing on what happened, but taking that into consideration [...] what's happening next, or what's happening now. How are they using this, you know, to better themselves or better other people?” Harris explained.

English teacher Katherine Fletcher shared an example of when incorporating trauma in an essay can work to a student’s advantage. “I read a very effective college essay last year about this student’s struggle to overcome her challenge with obsessive compulsive disorder [...] and how she wants to sort of live a functional life in spite of those challenges.” By concentrating on growth rather than struggles, the student was able to impress Fletcher and leave a lasting impact.

However, students should consider avoiding including traumas in their essays because traumatic moments don’t always demonstrate the best aspects of one’s personality. “If I was applying to college or any other part of my life, I would not want to feel obligated to be judged on my worst moments,” Henderson said. “I would want to be judged on the moments I'm proudest of.”

Grossman similarly believes that less intense topics can be just as powerful (if not more) than ones that address trauma. “One college essay I read that I really, really liked was my son’s. He wrote about [...] European castles and kind of like fantasized about what his life would be like if he could buy this one,” Grossman said. “I think the essay didn’t try to bare his soul [...] I don’t think that for the most part a college essay is for baring your soul. There isn’t enough room anyways—nobody’s soul is 600 words.”

At the end of the day, there is no one person to listen to when it comes to essay topics but yourself. After all, the criteria used by admissions officers to judge essays isn’t clear-cut, and depends heavily on the individual admissions officer who reads the essay. “None of us have ever let anyone into college. So none of us will truly know that secret, like ‘Here’s the one essay that will get you in,’” Henderson said.

Ultimately, it’s important for students to remember to stay kind to themselves throughout the grueling process of writing their college application essays, whether or not they choose to write about their trauma. The approach to writing about trauma often recommended in college applications—that is, demonstrating one’s growth from it—might not always align with the healthiest approach for the student’s healing process, and that’s okay. After all, the personal statement is essentially supposed to hold a mirror to the applicant’s truest self, so whatever the student decides to put on the page should unequivocally be their choice and reflect the parts of themselves that they are most comfortable sharing. Whether that includes trauma or not, the admissions officer should come away from the essay feeling as if they have seen the applicant in the clearest and most authentic way possible.

TED is supported by ads and partners 00:00

The rise of the "trauma essay" in college applications

- personal growth

- mental health

- Editor's Pick

‘A Big Win’: Harvard Expands Kosher Options in Undergraduate Dining Halls

Top Republicans Ask Harvard to Detail Plans for Handling Campus Protests in New Semester

Harvard’s Graduate Union Installs Third New President in Less Than 1 Year

Harvard Settles With Applied Physics Professor Who Sued Over Tenure Denial

Longtime Harvard Social Studies Director Anya Bassett Remembered As ‘Greatest Mentor’

College Essays and the Trauma Sweetspot

Recount a time when you faced a challenge, setback, or failure. Reflect on a time when you questioned or challenged a belief or idea. Discuss a period of personal growth and a new understanding of yourself or others. If all else fails, explore a background, identity, interest, or talent so profound that not doing so would leave our idea of you fundamentally incomplete.

Exactly the sort of small talk you want to make with strangers.

American college essays — frequently structured around prompts like the above — ask us to interrogate who we are, who we want to be, and what the most formative experiences of our then-short lives are. To tell a story, to reveal ourselves and our identity in its entirety to the curious gaze of admissions officers — all in a succinct 650 words.

Last Thursday, The Crimson published “ Rewriting Our Admissions Essays, ” an intimate reflection by six Crimson editors on the personal statements that got them into Harvard. Our takeaway from this exercise is that our current essay-generating ethos — the topics we choose or are made to choose, the style and emphasis we apply — is imperfect at best, when not actively harmful.

The American admissions process rightly grants students broad latitude to write about whatever they choose, with prompts that emphasize personal experience, adversity, discovery, and identity — features often distort student narratives and pressure students to present themselves in light of their most difficult experiences.

When it comes to writing, freedom is good — great even! The personal statement can be a powerful vehicle to convey an aspect of one’s identity, and students who feel inclined to do so should take advantage of the opportunity to write deeply and candidly about their lives; the variety of prompts, including the possibility to craft your own, facilitate that. We have no doubt that some of our peers had already pondered, or even lived in the shadow of, the difficult questions posed by the most recurrent essay prompts; and we know the essay to be a fundamental part of the holistic, inclusive admissions system we so fervently cherish . Writing one’s college essay, while stressful, can ultimately prove cathartic to some and revealing to others, a helpful exercise in introspection amid a much too busy reality.

Yet we would be blind not to notice the deep, dark nooks where the system that demands such introspection tends to lead us.

Both the college essay format — short but riveting, revealing but uplifting, insightful but not so self-centered that it will upset any potential admissions counselor — and the prompts that guide it push students towards an ethic of maximum emotional impact. With falling acceptance rates and a desperate need to stand out from tens of thousands of applicants, students frequently feel the need to supply the sort of attention-grabbing drama that might just push them through.

But joyful, restful days don’t make for great stories; there are few, if any, plot points in a stable, warm relationship with a living, healthy relative. Trauma, on the other hand — homophobic or racist encounters that leave one shaken, alcoholic parents, death, loss and scarring pain — makes for a good story. A Harvard-worthy story, even.

For students who have experienced genuine adversity, this pressure to package adversity into a palatable narrative can be toxic. The essay risks commodifying hardship, rendering genuinely soul-molding experiences like suffering recurrent homelessness or having orphaned grandparents into shiny narrative baubles to melt down into a Harvard degree. It can make applicants, accepted or not, feel like their admissions outcomes are tied to their most vulnerable experiences. The worst thing that ever happened to you was simply not enough, or alternatively, it was more than enough, and now you get to struggle with traumatized-imposter syndrome.

Moreover, students often feel compelled to end their essays about deep trauma with a statement of victory — a proclamation that they have overcome their problems and are “fit for admission.” Very few have figured life out by age 18. Trauma often sticks with people far longer, and this implicit obligation may make students feel like they “failed” if the pain of their trauma resurfaces during college. Not every bruise heals and not all damage can be undone — but no one wants to read a sob story without a redemption arc.

A similar dynamic is at play in terms of the intensity of the chosen experience: Students feeling for ridges of scars to tear up into prose must be careful to avoid cuts too deep or too shallow. Their trauma mustn’t appear too severe: No college, certainly not Harvard, wants to admit people who could trigger legal liabilities after a bad mental health episode . That is the essay’s twisted pain paradox — students’ trauma must be compelling but not too serious, shocking but not off-putting. Colleges seek the chic not-like-other-students sort of hurt; they want the fun, quirky pain that leaves the main character with a new refreshing perspective at the end of a lackluster indie film. Genuine wounds — the sort that don’t heal overnight or ever, the kind that don’t lead to an uplifting conclusion that ties in beautifully with your interest in Anthropology — are but lawsuits in the waiting .

For students who have not experienced such trauma, the personal essay can trap accuracy in a tug of war with appealing falsities. The desire to appear as a heroic problem-solver can incentivize students to exaggerate or misrepresent details to compete with the compelling stories of others.

We emphatically reject these unspoken premises. Students from marginalized communities don’t owe college admissions offices an inspirational story of nicely packaged drama. They should not bear a disproportionate burden in proving their worthiness.

Why, then, do these pressures exist? How can we account for the multitude of challenging experiences people have without reductionist commodification? How do you value the sharing of deeply personal struggles without incentivizing every acceptance-hungry applicant to offer an adjective-ridden, six-paragraph attempt at psychoanalyzing their terrible childhood?

We don’t have a quick fix, but we must seek a system that preserves openness and mitigates perverse pressures. Other admissions systems around the world, such as the United Kingdom’s UCAS personal statement, tend to emphasize intellectual interest in tandem with personal experience. The Rhodes Scholarship, citing an excessive focus on the “heroic self” in the essays it receives, recently overhauled its prompts to focus more broadly on the themes “self/others/world.” We should pay attention to the nature of the essays that these prompts inspire and see, in time, if their models are worth replicating.

In the meantime, students should understand that neither their hurt nor their college essay defines them — and there are many ways to stand out to admissions officers. If it feels right to write about deeply difficult experiences, do so with the knowledge that they have far more to contribute to a college campus than adversity and hardship.

The issue is not what people can or should write about in their personal statements. Rather, it’s how what admissions officers expect of their applicants distorts the essays they receive, and how the structure of American college admissions can push toward garment-rending oversharing. We must strive for an admissions culture in which students feel truly free to express their identity — to tell a story they want to share, not one their admissions officers want them to. A system where students can feel comfortable that any specific essay topic — devastating or cheerful — will not place them slightly ahead or behind in the mad, mad race toward that cherished acceptance letter.

This staff editorial solely represents the majority view of The Crimson Editorial Board. It is the product of discussions at regular Editorial Board meetings. In order to ensure the impartiality of our journalism, Crimson editors who choose to opine and vote at these meetings are not involved in the reporting of articles on similar topics.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.

Login or sign up

Get Started

- College Search

- College Search Map

- Graduate Programs

- Featured Colleges

- Scholarship Search

- Lists & Rankings

- User Resources

Articles & Advice

- All Categories

- Ask the Experts

- Campus Visits

- Catholic Colleges and Universities

- Christian Colleges and Universities

- College Admission

- College Athletics

- College Diversity

- Counselors and Consultants

- Education and Teaching

- Financial Aid

- Graduate School

- Health and Medicine

- International Students

- Internships and Careers

- Majors and Academics

- Performing and Visual Arts

- Public Colleges and Universities

- Science and Engineering

- Student Life

- Transfer Students

- Why CollegeXpress

- CollegeXpress Store

- Corporate Website

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- CA and EU Privacy Policy

Articles & Advice > College Admission > Blog

How to Approach Tragedy and Loss in Your College Essay

You may feel compelled to write about a difficult subject for your college essay. Here are some tips to write about hard topics with respect and impact.

by Keaghan Turner, PhD Partner, Turner+Turner College Consulting

Last Updated: Mar 16, 2023

Originally Posted: Aug 5, 2019

Tragedy and loss are not easy subjects to broach in writing at all, let alone very public writing that someone else will read or hear spoken. Writing about tragedy and loss certainly won’t be for everyone, so make sure you give it some real thought before you try to dive in and put your jumbled, high-emotion thoughts to page. But if a difficult topic is the one that compels you to write a great admission essay, then it can be done—as long as it’s done the right way. Before we explore the key elements to writing about traumatic experiences the right way, here’s some perspective through a personal story of loss.

The struggles with writing about loss

One spring, there was a rash of suicide attempts at a local high school in my community. Two of them were successful; others were not. The first time I wrote about this loss was for a memorial service. This is the second time. It’ll never be “easy” to write about, just as what happened will never make sense to anyone who knew the victims. How can we use words for trauma and grief in order to make sense of what doesn’t make sense?

One student, in a mature spirit of activism, wrote an open letter to the school district office, which was posted and reposted all over social media until there was a school assembly featuring officials, professionals, and faith leaders open to the whole community. The Parent Teacher Organization gave out green ribbons to raise awareness about depression and other mental illnesses . Most immediately for the teens in my town, the words appeared via social media posts. That was how the students wrote about their loss in the weeks following the first (then six weeks later, the second) tragedy. Some students will write about it for their college essays, and they’ll need help. It’ll be important to them to do a good job, to honor the memories of their friends who passed away, to get it “right.”

To say the least, people had mixed feelings about these posts and reposts; about what should be discussed and how; and how to protect the grieving families from more suffering. It’s a small community, and these were shockingly sad events. The fact is, these tragedies have already fundamentally redefined the high school experience of the students in my town. The ripples might be subtle or pronounced, but they exist. Peers will mark time using these losses (midterms happened before , prom happened after ), and the experience will not be forgotten; it’s now part of their life stories.

Related: Mental Health: What Is It and How You Can Find Help

How to tackle writing about tragedy the right way

Difficult topics can ( and should) be broached in admission essays because they are a part of life that can’t be ignored and often play a huge part in defining who we are as people. What I told those students about handling loss with their words is summed up below, and it also applies to writers tackling any kind of special need, medical condition, or family struggle in their college essay.

Be honest and straightforward

You don’t need to have been super close to a tragedy to be affected by it or to write about it effectively. But don’t pretend you were affected in a way you weren’t; you’ll come across as phony. If you’re moved to write about a painful event, there’s a genuine reason behind that impulse. That reason is good enough; figure out what it is. That being said, powerful life events require quick-hitting, direct sentences. Be like Hemingway, my professors used to say—keep your sentences short; they have more punch that way. You don’t need lots of flowery or figurative language to convey that your subject is a big deal—but at the same time, do make sure you’re showing, not telling, in your writing . Connecting emotionally is about expressing that time through actions and events, not just thoughts and feelings.

Find your message with the right words

Superfluous language gets in the way of gravity. Be ready to prune drafts until you feel you’ve found the right semantic fit for the intention behind your words. Your essay also needs a theme, a call, a purpose. The point isn’t simply to narrate a sad story in order to show the reader how sad it is (e.g., your essay’s message is not that teen suicide is tragic); rather, the point is to connect the sad story to the essay prompt you've chosen to address. The event itself essentially takes a backseat to the points you want to make about what it means .

Be respectful

This is really the one ultimate rule, and if you do this, the other stuff can be worked out. In the context of the college essay, respect usually involves approaching your subject matter somewhat anonymously. Names aren’t necessary. If you’re engaging a serious, painful topic—and it involves others—be careful to write as circumspectly and thoughtfully as you can. When in doubt, ask someone whose judgment you trust (like a teacher or parent) to check it out for you.

Seek help for you or others

Is it easy to write about hard realities? Not at all—not in any context, not for anyone. But if you’re brave enough to try, you may find it to be transformative and therapeutic to articulate your experience as you process your grief and begin to heal. And the most important thing to remember is to take those emotions and experiences and use them to help others in the future before other tragedies strike. Writing about these situations can often shed light and inspire others to help people in need, which in the end is more crucial than anything else. If you have been affected by tragedy or are worried about a friend who is struggling, help is available. Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline 800-273-8255 or a trusted adult.

For more advice on college essays, check out our Application Essay Clinic , or if you’re in need of mental health advice, check out the tag “mental health.”

Like what you’re reading?

Join the CollegeXpress community! Create a free account and we’ll notify you about new articles, scholarship deadlines, and more.

Tags: admission essay college admission college essay mental health writing tips

← Previous Post

Next Post →

About Keaghan Turner, PhD

Keaghan Turner, PhD, is Assistant Professor of Digital Writing and Humanistic Studies at Coastal Carolina University . She has taught writing and literature at small liberal arts colleges and state flagship universities for the past 20 years. As a managing partner of Turner+Turner College Consulting, LLC, Dr. Turner also counsels high school students on all aspects of their college admission portfolios, leads writing workshops, and generally tries to encourage students to believe in the power of their own writing voices. You can contact Dr. Turner on Instagram @consultingprofessors or by email at [email protected] .

Join our community of over 5 million students!

CollegeXpress has everything you need to simplify your college search, get connected to schools, and find your perfect fit.

College Quick Connect

Swipe right to request information. Swipe left if you're not interested.

University of Nevada-Reno

St. Catherine University

St. Paul, MN

Emerson College

Eastern Washington University

Southern New Hampshire University

Manchester, NH

Charleston Southern University

North Charleston, SC

Western Washington University

Bellingham, WA

Ithaca College

Agnes Scott College

Atlanta, GA

University of Cincinnati

Cincinnati, OH

Lynn University

Boca Raton, FL

Pace University

New York, NY

The University of Tampa

Fordham University

Millikin University

Decatur, IL

The College of Staten Island, CUNY

Staten Island, NY

Gonzaga University

Spokane, WA

University of Mount Union

Alliance, OH

Georgian Court University

Lakewood, NJ

Felician University

High Point University

High Point, NC

Caldwell University

Caldwell, NJ

Ohio University

That's it for now!

High School Class of 2021

CollegeXpress helped me organize the schools I wanted to choose from in one place, which I could then easily compare and find the school that was right for me!

Farrah Macci

High School Class of 2016

CollegeXpress has helped me in many ways. For one, online searches are more organized and refined by filtering scholarships through by my personal and academic interests. Due to this, it has made searching for colleges and scholarships significantly less stressful. As a student, life can already get stressful pretty quickly. For me, it’s been helpful to utilize CollegeXpress since it keeps all of my searches and likes together, so I don’t have to branch out on multiple websites just to explore scholarship options.

Melanie Kajy

CollegeXpress has helped me tremendously during my senior year of high school. I started off using the college search to find more information about the universities I was interested in. Just this tool alone gave me so much information about a particular school. It was my one-stop shop to learn about college. I was able to find information about college tuition, school rank, majors, and so much more that I can't list it all. The college search tool has helped me narrow down which college I want to attend, and it made a stressful process surprisingly not so stressful. I then moved to the scholarship search tool to find scholarships to apply for because I can't afford to pay for tuition myself. The search tool helped me find scholarships that I was eligible for. The tool gave me all the information I could ever need about a particular scholarship that was being offered. The CollegeXpress scholarship search tool is so much better than other tools offered, like the Chegg scholarship search. Thanks to CollegeXpress, I was able to apply to tons of scholarships in a relatively easy way!

CollegeXpress gave me options of schools with my major and from there I was able to pick what was most important to me in a school. Everything was so organized that I could see all the information I needed.

High School Class of 2022

My mother signed me up for a couple of scholarship contests through CollegeXpress. I was also able to do some research and compare the different schools on my list. I was able to see the graduation rates and different programs that helped me decide on Adelphi University. I will continue looking for some scholarships for my start in September.

Personalize your experience on CollegeXpress.

With this information, we'll display content relevant to your interests. By subscribing, you agree to receive CollegeXpress emails and to make your information available to colleges, scholarship programs, and other companies that have relevant/related offers.

Already have an account?

Log in to be directly connected to

Not a CollegeXpress user?

Don't want to register.

Provide your information below to connect with

Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic

This module give writers tools to compose personal healing narratives, to frame their personal inquiries within a larger research context, and to position themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through this public teaching initiative, we ask “How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience?”

Living through the current pandemic is not only about the medical and financial fall-out of COV-SARS-2 and COVID-19 illness, but also about the lasting trauma that has been felt by individuals as they, their families, and communities struggle during this historical time. Storytelling is a means of healing from trauma. This module give writers tools to compose personal healing narratives, to frame their personal inquiries within a larger research context, and to position themselves within the larger community response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, we draw upon research on trauma theory, research on expressive writing and healing, and research on responding to writing. Through this public teaching initiative, we ask “ How can we transform the trauma we experience in the current COVID-19 pandemic into a reflective moment that inspires resilience ?”

- any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation , confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s attitudes, behavior, and other aspects of functioning. Traumatic events include those caused by human behavior (e.g., rape, war, industrial accidents) as well as by nature (e.g., earthquakes) and often challenge an individual’s view of the world as a just, safe, and predictable place.

- Any serious physical injury, such as a widespread burn or a blow to the head. —traumatic adj.

All the modules in this series are based on the following four principles of trauma-informed care and teaching:

Connectedness–valuing of relationships

Protection–ensuring safety and trustworthiness

Respect–promoting choice and collaboration

Hope–Resilience and Change

(Adapted from Hummer, Crosland, & Dollard, 2009)

Writing and Responding to Trauma in a Time of Pandemic includes the following components:

- The personal entry point with personal written and oral healing narratives

- The inquiry entry point for writers who want to pursue self-generated research inquiries related to Covid-19

- The community entry point , which supports writers as they position themselves within larger community responses to Covid-19

- A comprehensive online bibliography on trauma, writing, and response

This module was created as part of Northeastern University’s College of Social Science and Humanities Pandemic Public Teaching Initiative. The Pandemic Teaching Initiative, which is supported by the CSSH Office of the Dean, the Northeastern Humanities Center, the Ethics Institute, the SPPUA and the NULab, seeks to create a library of publicly accessible modules that explore topics related to pandemics and their disruptions and impacts.

All of the prompts will generate material that will be shareable, if participants wish, during an open, online event series.

We have attempted to limit traumatic content in the main text of this module, but the examples used in the following modules may be disturbing for some individuals. Examples include sexual violence, racism, COVID-19 illness, and death.

This session offers an overview of expressive writing and storytelling as a means of healing. This session follows four steps:

- Identify the basic research supporting expressive writing

- Identify narrative strategies and discuss examples of types of healing narratives to help you better understand the narrative techniques and strategies you will learn.

- Complete informal writing prompts that offer you the opportunity to begin applying these strategies to your own writing.

- Use informal writing prompts to build towards a full-length healing narrative and recognize elements of effective feedback.

- Reading: Chip Scanlan, “What is Narrative, Anyway?,” Poynter

This session offers an overview of expressive writing, which is writing that pairs emotions with events and action with reflection. It also offers some of the research into writing about trauma as a means of healing, as well as examples of published written and oral healing narratives. This basic grounding in the literature of expressive writing and healing will support the specific narrative entry points for writers that appear in subsequent modules.

Expressive writing is a specific type of narrative writing that combines experiences with reflection and insight. Often, we’re more familiar with straight journaling or chronicling events in a diary, but it is the interplay between emotions and events and the ability to distinguish feelings from the past and the present in expressive writing that distinguishes it.

Expressive Writing

- Does more than simply record events

- Does more than simply vent feelings

- Includes action and reflection

- Includes descriptive and/or figurative language

As defined by Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing , 2000, Chapter 2.

- Video: The Expressive Writing Method

- Video: What Does Expressive Writing Look Like

- Reading: Oliver Glassa, Mark Dreusickea, John Evansa, Elizabeth Becharda, and Ruth Q. Wolever, “Expressive Writing to Improve Resilience to Trauma: A clinical Feasibility Trial,” Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice

- Reading: James W. Pennebaker, “Expressive Writing in Psychological Science,” Perspectives on Psychological Science

- Reading: Kimberly Mack, “Johnny Rotten, My Mom, and Me,” Longreads

- Reading: Tracy Strauss, “Writing Trauma: Notes of Transcendence,” The Ploughshares Blog

- Reading: Ann Wallace, “A Life Less Terrifying: The Revisionary Lens of Illness,” Intima

- Podcast: My Brain Explosion

- Questions to Consider:

- Once you’ve read the essays and articles and watched the two videos that accompany this session, think about how expressive writing is different from other types of writing you may have done (journaling, expository writing, etc.) What do you see as the biggest opportunities and challenges of this type of writing?

In this session, you will learn about three specific types of wounded body/healing narratives as classified by Louise DeSalvo: the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative. The suggested readings offer elements of these types of healing narratives. In addition, the Strauss piece offers a useful frame for how to pair emotion with reflection/insight in expressive writing, which you will be able to apply to your own writing in the next session.

- Reading: Alison Rosalie Brookes, “Love and Death in the time of Quarantine,” Health Story Collaborative

- Reading: Nina Collins, “Graduations,” Intima

- Reading: Tracy Strauss, “Writing Trauma: Notes of Transcendence, #4—The Situation and the Story,” The Ploughshares Blog

- Reading: Jennifer Stitt, “Will COVID-19 Strengthen our Bonds?,” Guernica

- Reading: Adina Talve-Goodman, “I Must Have Been That Man,” Bellevue Literary Review

- Reading: Jesmyn Ward, “On Witness and Respair: A Personal Tragedy Followed By a Pandemic,” Vanity Fair

- Types of Healing Narratives/Wounded Body Narratives Tip : Often, healing narratives have elements of more than one of these frameworks—for example, particular passages in a quest narrative may take on the immediacy and visceral feel of a chaos narrative. You will likely identify elements from more than one of these frameworks in the published essays in this session.

- Once you’ve looked at the chart above and the accompanying essays, think about which types of healing narratives (chaos, restitution, and quest) you would characterize them. Which essay or essays resonate the most with you, and what narrative elements/strategies account for that–can you point to specific moments in the text?

In this session, you can apply what you’ve learned about different types of healing narratives and from the sample published essays to formative writing activities. Please choose as many of these short, informal writing exercises as you would like, keeping in mind the fundamentals of expressive writing, i.e., linking emotions with events. Start with 15 minutes on a prompt and see how far you get.

Activities :

- As Ann Wallace asks in “ A Life Less Terrifying,” write a journal entry about a time when you were denied some kind of essential or fundamental human need—love, compassion, respect, dignity, shelter, the possibilities are many. If you’d like, you can focus this within the context of COVID-19 and your experiences living through it.

- Thinking about a time you were denied a fundamental need, now try writing a letter to someone as a means of telling this story. Think about the differences in your story that arise when you address this towards an intended reader.

- Draw a map of a meaningful landscape from your COVID-19 experience (e.g., where you’ve spent the most time) including as many details as possible. Think about 2-3 specific memories/events that have taken place in that space, and make a list of as many sensory details as possible–what sounds, smells, touch, images, etc. do you associate with this place and these memories? Use this sensory list to start writing about your experiences during COVID-19.

- What family story or generational tale do you wish had a different ending? What would it look like? Alternatively, what COVID-19 story would you re-write if you could?

Looking for additional short prompts specific to COVID-19? Check out The Pandemic Project, directed by James Pennebaker.

Optional revision activity:

Have a response to a writing prompt you want to deepen? Consider using Strauss’s Situation and Story essay for the following activity: Make a two-column chart where you identify the actions/plot points in your narrative (the situation) and a column where you reflect on the emotions of the event (the story). This will help highlight places where the pairing of emotions with events and action with reflection could be developed.

We’ve discussed the different kinds of wounded body narratives classifications (the chaos narrative, the restitution narrative, and the quest narrative), and have read a variety of healing narratives that deal with trauma, loss, illness, etc. To draft your own healing narrative, take these three frameworks and the formative writing you’ve done in Session 1.3 surrounding this denial of a fundamental need as a foundation for a longer essay where you explore a seminal event or trauma in your own life. If you would like to focus this writing on events related to COVID-19 you may, but you are not limited to that. As you write, think about the qualities of healing narratives DeSalvo mentions, and the characteristics/criteria for successful healing narratives included in this session. Above all, healing narratives pair emotions/feelings with events.

Once you’ve drafted your healing narrative using the prompt above, we recommend getting feedback on it so you can continue to deepen and order the draft.

Getting feedback on your healing narrative:

You might find that you want to share your narrative with someone you trust or even present your narrative in a public forum. Before you share your work, however, you want to think about the feedback you may receive. If you simply ask a friend to give you feedback on your narrative, they may give you bad advice. For example, they may only tell you about grammatical errors or, worse yet, debate the content of your narrative.

Because most readers are not familiar with healing narratives, it’s useful to give them some guidance on how to respond to your writing. Two tips are helpful here:

1. Content-based response. Based on the research and work of Louise DeSalvo, ask readers to focus on the following characteristics of effective healing narratives.

Elements of a Healing Narrative

- Renders our experience concretely, authentically, explicitly, and with a richness of detail

- Links feelings to events, including feelings from the past versus feelings in the present

- Is a balanced narrative that uses negative words but also includes the positive and that continues to evolve

- Reveals the insights we’ve achieved from painful experiences

- Tells a complete, complex, coherent story that can stand alone and can take multiple forms

Louise DeSalvo, Writing as a Way of Healing: How Telling Stories Transforms Our Lives , pgs. 57-61

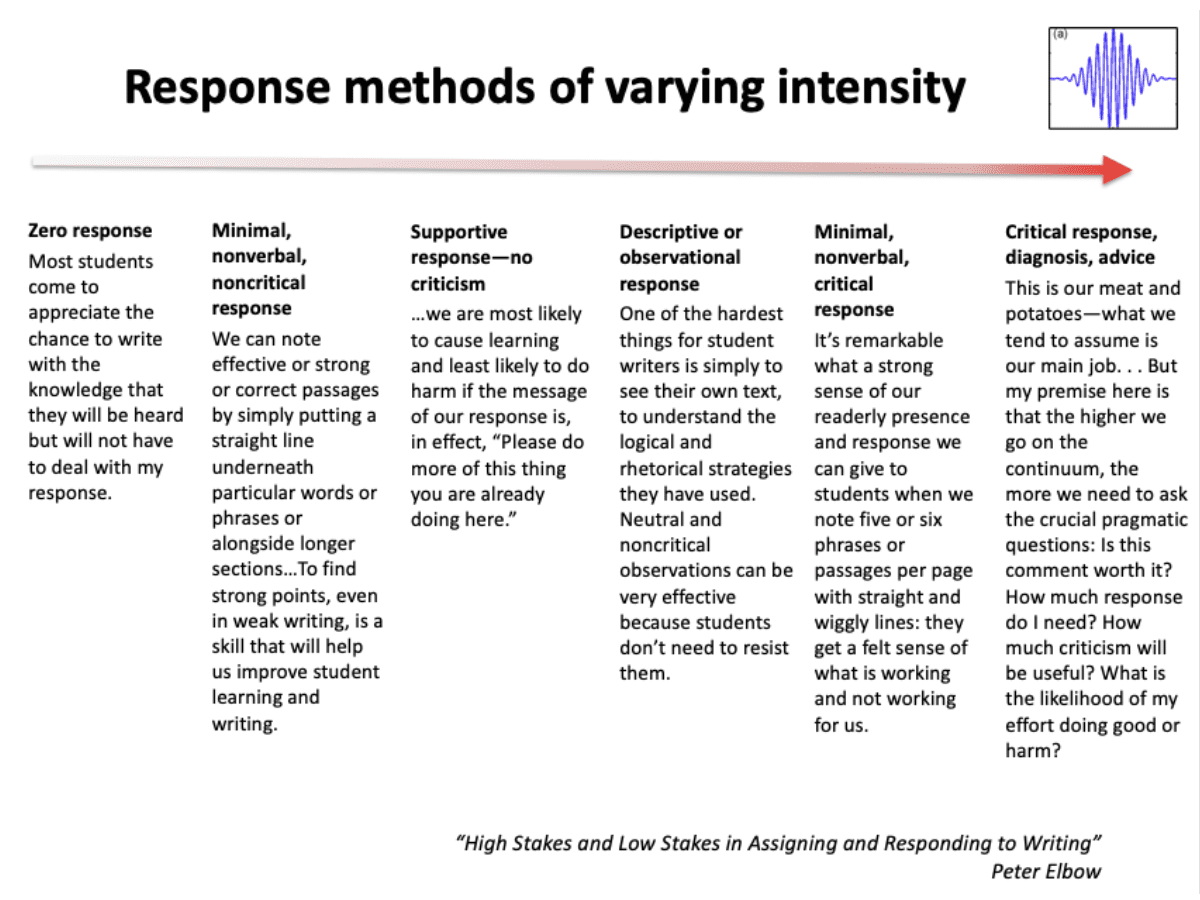

2. Intensity of response. Rather than having readers give you critical response or diagnosis , readers might offer supportive response to help you build on what you are already doing well.

While individuals find it therapeutic to write stories or narratives about their personal experiences related to COVID-19, other individuals find it helpful to learn more about the disease and its implications. Inquiry-based writing is a powerful way of harnessing the potential of research to answer the questions that most interest you.

This session will offer participants who want to process the implications of the pandemic through research. Activities in this session guide writers through the research process. These activities help writers refine the skills necessary to bring self-generated research inquiries into the public sphere, whether for education, awareness, or call to action. This session follows four steps:

- Identify what inquiry is and types of inquiry-based writing.

- Generate and evaluate inquiry questions.

- Find and evaluate scholarly and popular sources on COVID-19.

- Translate health/science information accurately and responsibly into an essay, report, or presentation.

- Reading: “The Color of Coronavirus: Covid-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S.,” Apm Research Lab Staff

- Reading: Michael Ollove and Christine Vestal, “COVID-19 Is Crushing Black Communities. Some States Are Paying Attention,” PEW

Like the first session on personal/narrative writing, inquiry-based writing starts with your values, your experiences, and your goals and interests, and that is what you will focus on in this module. This session will cover the basic considerations of inquiry-based writing, before we move into generating questions and drafting your own research inquires.

Inquiry is the process of asking questions to solve a problem. In education, inquiry-based learning is a way for students to generate research questions for further study and, thus, model the work of professional researchers. In this way, teachers become guides for students, rather than assigning research topics.

Inquiry-based writing instruction has been shown to provide more meaningful learning for students and keep students engaged. In inquiry-based writing, students can draw on personal connections in their writing and research (Eodice, Geller & Lerner, 2019; Geller, Eodice, & Lerner, 2016). When combined with clear expectations for writing and the opportunity for supportive feedback from a peer, such activities lead to deeper learning and personal development (Anderson et al., 2016).

Inquiry-based writing can be a potentially positive way to address trauma because it gets writers to focus on action. It is a way to build resilience.

- Reading: Louise Aronson, “Story as Evidence, Evidence as Story,” A Piece of My Mind

- Reading: “Responsible Science: Ensuring the Integrity of the Research Process,” National Library of Medicine

- Reading: Carl Zimmer, “How You Should Read Coronavirus Studies, or Any Science Paper,” The New York Times

Inquiry-based research is driven by the ongoing relationship between asking questions, seeking information, and refining the questions based on what you find. In this session, you will find resources and activities to help you frame your questions. From there, you can work on activities related to data gathering and data analysis.

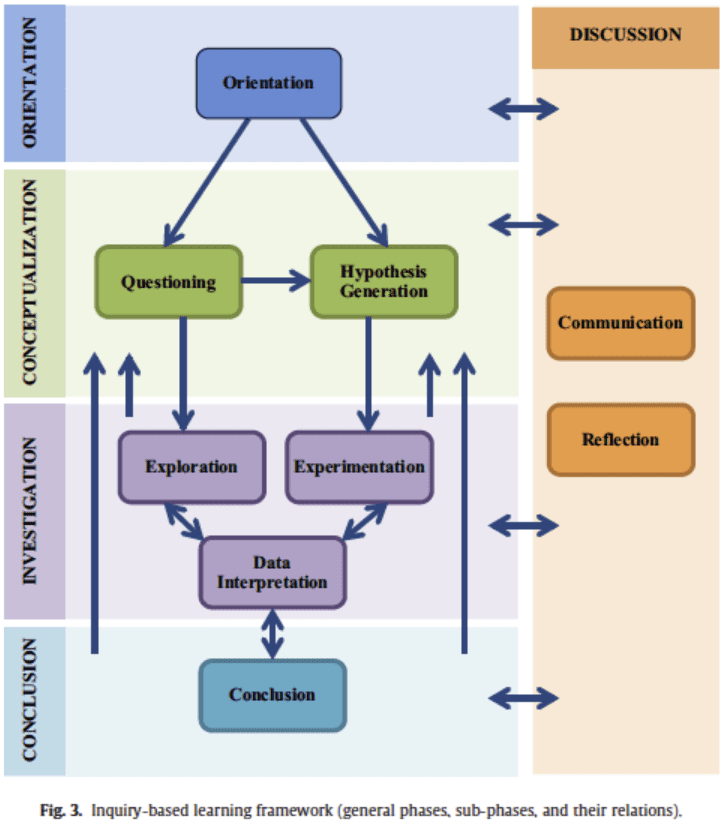

Inquiry-based research typically includes four phases: (1) orientation, (2) conceptualization, (3) investigation, and (4) conclusion. Discussion happens throughout the process

Session 2.2: Phase 1: Orientation

1. Orientation. Inquiry-based research starts with orienting yourself toward a topic. In other words, you want to find a topic to write about.

Orientation questions:

Using some of the COVID-19 healing narratives you composed in Module 1, or using your personal experiences living through the pandemic thus far, consider if there are potential research topics you can extract from these personal narratives.

- What are some COVID-19 topics that interest you?

- Why are you interested in those topics?

- Why are they relevant to your personal and/or professional experiences?

- What is your ultimate goal? Do you want to write an op-ed, give a public talk, write a research article, or something else?

At this early stage in the research process, we ask about your ultimate goal. That’s because no professional researcher waits until the end to think about writing. In fact, what we want to write often shapes how we go about conducting research, including how much research we do and what kinds of sources we use. For example, if we want to write an op-ed, we might only need 5-8 good sources. On the other hand, if we want to write a research article, we might need 20 or more sources.

Discussion : Often it is helpful at the beginning of a project to discuss your ideas with someone else. Talking to someone else can help you identify what really interests you. You can even brainstorm new ideas with a friend.

After orienting yourself to a topic, take a step back. When working on trauma-informed inquiry, we recommend some introspection before proceeding with your research. Professional researchers call the process of examining our own values, goals, and beliefs in relation to our research and teaching “ reflexivity .”

Besides being helpful in understanding your values, goals, and beliefs in relation to your research, self-reflexive exercises can also help you think about the impact of your search on readers.

Self-reflexive questions:

- Why do I find this topic personally interesting?

- How does my identity impact my research interest and the ways I might answer my research questions?

- What potential harm might I do to myself by conducting this research? Are there triggers that I should consider before starting?

- What do I hope will come of my research? What will I do if I do not get the response that I hope for?

- Who might be helped by my research? Who might be harmed by my research?

Who do I want to read my research? Why them? What do I hope will be their reaction?

Session 2.2: Phase 2: Conceptualization

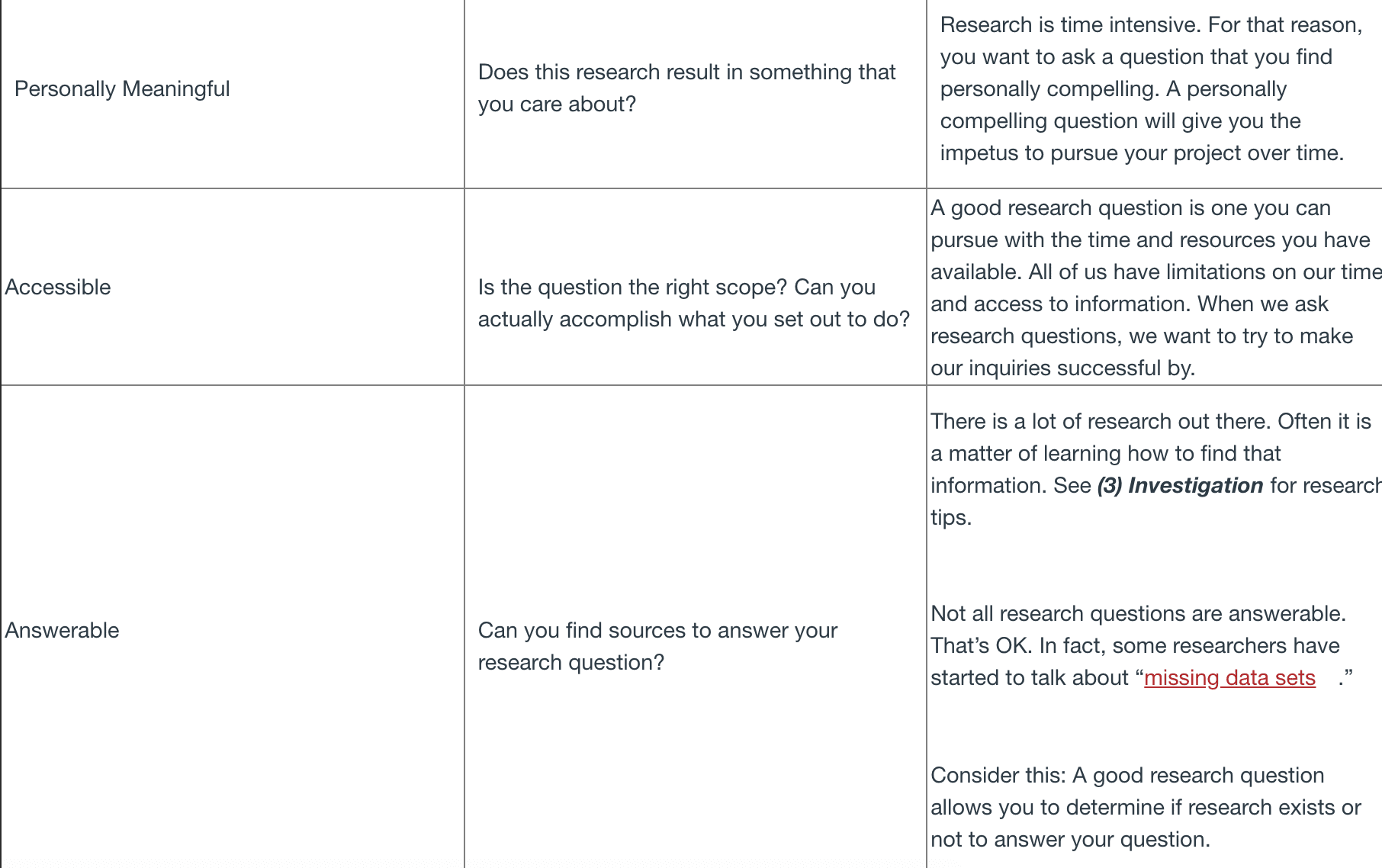

Conceptualization . Conceptualization is a complicated way of saying “asking questions” and generating some ideas (or hypotheses) about what you might find through your research. The trick to making inquiry-based research “good” is in asking good questions. A good research question is personally meaningful, accessible, and answerable.

Asking questions activities

Using the research topics you generated in (1) Orientation , begin to generate some research questions.

When you begin to generate research questions, don’t worry about good grammar or logic. Instead, try to think of as many questions as you can. Here are some to get you started:

- What topic is it that you want to learn?

- What is known about this topic?

- Who does this topic affect?

- What are some of the issues of conflict surrounding this topic?

- What are some aspects of your topic that are unknown right now?

- What might be some outcomes or uses of your inquiry?

- Using the fake news/fact-checking sites and the resources on how to find scholarly sources, briefly, how is the topic being discussed in popular and academic circles right now?

After you generate a list of potential research questions, ask yourself:

- How passionate do I feel about this topic? Who am I accountable to in doing this research? Am I doing this research for myself or someone else?

- Can I narrow my topic by age, time, geography, or some other way? What keywords are central to my research? For example, can I change generic words like “people” to specific words like “infants” or “senior citizens”?

- What sources might I be interested in reviewing to answer my question? What do I expect to find?

With the questions above as a frame, write a brief paragraph in which you narrow the focus and specify your inquiry issue/topic.

Session 2.2: Phase 3: Investigation

(3) Investigation . Now that you have a working research question, it’s time to start finding research. Adding research to your writing is a way to provide more context for your discussion and build your ethos as a writer. And it’s a great way to learn. “Sources” can include everything from newspapers and online forums to peer-reviewed scientific articles. Academic research, such as scientific articles, are published in “journals,” such as The New England Journal of Medicine

Collecting Sources

While a Google search will certainly generate a lot of information, it may not be the best information to answer your research question. Google searches take you to all kinds of websites, ranging from reputable research sources to idiosyncratic blogs. Google Scholar is a bit better but can often produce results that are difficult to filter and sort. Professional researchers use academic databases to locate “peer-reviewed” research.

The Northeastern University librarians have put together a video series on how to find academic sources. For example, in this series, they discuss how to use a search engine called Scholar OneSearch to find academic research articles. In this series, they explain how to improve your search strategies and find ebooks.

Beyond academic sources, government sources are really valuable in finding public health information (Note: government websites always end in .gov). In fact, many professional researchers regularly use websites like the Centers for Disease Control website to find information about disease rates. In addition to federal websites, states often have local information available on their websites. For example, this website has Massachusetts-specific information

Before the COVID19 pandemic, many academic articles were behind a “firewall,” meaning you had to pay to get access to the article. However, many academic journals have now provided free access to COVID-19 research in an attempt to help the public learn more about the disease.

Analyzing sources . How do you know whether a source is reliable or not? In general, academic sources are better than non-academic sources when you are conducting research. Professional researchers evaluate the quality of sources by looking at a few key markers:

- Type of source

- Author expertise

- Publication date

- Publication venue

- Research quality

The Northeastern library has excellent guides on how to evaluate sources, including data and statistics

Fake News and Fact-Checking Covid Sites

You can find a lot of incorrect information on COVID-19 on the internet. Below are some resources to help assess your sources.

Facts in the Time of Covid-19

Fake or Real? How to Self-Check the News and Get the Facts

False, Misleading, Clickbait-y, and/or Satirical “News” Sources

How To Avoid Misinformation About Covid-19

Poynter International Covid-19 Fact Checking Site

WHO Covid-19 Myth Busters

Investigation activities:

Now that you have collected some sources on your topic, it’s time to review them critically before writing up your research. What kinds of sources has your search yielded? What information is provided in those sources? What information do you still need?

For each source, ask the following questions:

- What is this source–for example, a blog, scientific study, op-ed, or government report? Is it relevant? What genre is it? Is this source based on opinion or facts?

- Who is the author? What expertise do they possess?

- When was the article published? Does it contain timely information?

- Where was the source published? Is that a reputable journal or impartial news source? If it is a scholarly source, does the journal have an impact factor–that is, an indicator that other researchers cite research from the journal? Has the article been cited? Was it peer reviewed?

- How was the research conducted? Where was the research conducted?

After reflecting on the results of your research and what that research has yielded, you may decide to go back and do some more research. Try finding new sources if you cannot answer the questions above. Also, it’s not uncommon to find gaps in your research at this stage. You may need to go do more research, if you haven’t found exactly what you need to answer your research question.

- Question to Consider:

At this point in a research project, it’s very helpful to talk to someone about your research. By explaining what you are researching and what you have found, you are synthesizing your research findings into chunks of information. That chunking will help you both process what you have learned and help you consider what else you might want to know.

Session 2.2: Phase 4: Conclusion

(4) Conclusion . After you have found and analyzed sources to answer your research question, you need to figure out what to say. Professional researchers sometimes call this a “story,” and many professional researchers talk about the “story” of their research. A good research project reads like a story–there is a question, a search for answers, and …. ANSWERS!

So, how do you tell a good story with all the information you have found?

One way is to use a storyboard. There is no one right way to make a storyboard. It can be as simple as bullet points, a traditional outline, or a series of images. A storyboard or outline also helps you figure out where you need research in your story. After all, no one wants to read a series of research summaries. Readers want a presentation, essay, or report that is punctuated with research findings.

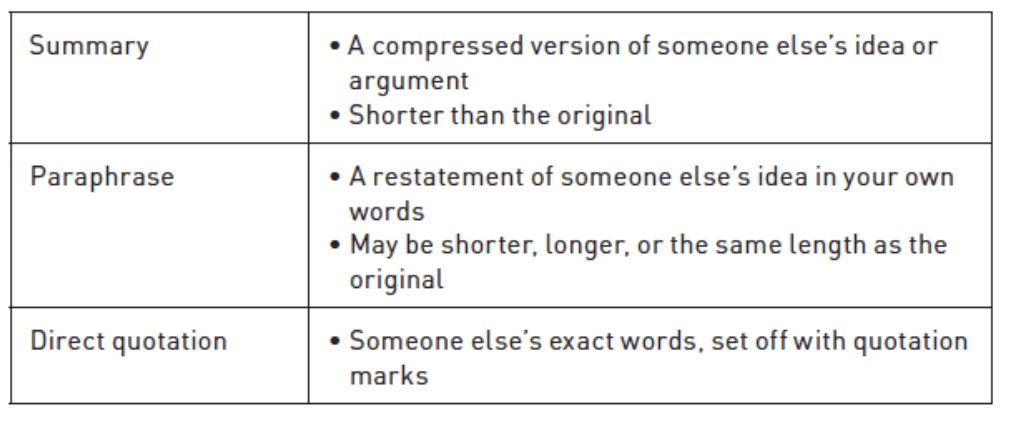

Once you figure out where you want to add research in your presentation, essay, or report, you need to decide how you will use that research. There are three main ways that writers include research: summary, paraphrase, and direct quotation.

How to Summarize

Summarizing involves a specific process of converting what you have read into a much shorter version. The process can generally be handled in four steps:

- Identify the main claim and write it in your own words. Often, you will find it easiest to write this if you read the abstract, introduction, and conclusion of an article. The main claim is usually most developed in these sections. If someone were to ask you, “What is this about?” this statement would be your answer.

- Explain the main arguments that support this claim. You can omit aspects that are not central to supporting the claim, such as specific details or examples.

- Include necessary context. Sometimes a small amount of context, such as the circumstances of the research, can be helpful to understanding the claim or conclusions.

- Avoid personal opinion or interpretation of the original. This point holds true for students working on summary assignments for school but may be “bent” in professional writing, depending on the purpose and audience. (Irish, 2015, p. 209-210)

Make sure that if you are summarizing, paraphrasing, or quoting someone else’s ideas or words that you cite your source . Usually a citation includes an in-text reference and an entry in a References page. The Northeastern University guide to citing sources is a good resource for learning the different ways of using sources.

Conclusion activities:

Now that you have found good sources that help you answer your research question, it’s useful to take a step back before writing up your findings. At this moment, you are “close” to your work, which means that you may not see gaps or strengths in your research process. Talking to a friend can help you get some perspective. The following questions can also help you self-assess your work:

- What are the main themes, ideas, or findings that I find most compelling from my research?

- What assertions can I support with the sources I have found? Do multiple sources support those assertions?

- Have I answered my research question? If not, do I need to change my original research question?

- How do I feel about this research? Have I learned something? How has that new knowledge changed me?

- What might happen based on my research? What might be a positive effect? A negative effect?

In this session, you will take the results of your initial inquiry activities and research analysis from the first two sessions and produce a piece of accessible research writing.

Now that you know how to ask a research question, conduct research, and analyze your findings such that you can make a storyboard or outline, it’s time to finish drafting your presentation, report, or essay.

While many writers compose narratives chronologically, research writers tend to compose their texts in chunks. They might write a short introduction to frame the main idea of their report or presentation, but then move to the center of the report or presentation to work on a key idea. By using a storyboard or outline, you can easily move around in your report or essay to different sections and not lose the overall coherence of your work. This nonlinear composing process also helps with fatigue when working with complex research.

Getting feedback on your inquiry-based writing:

While inquiry-based writing can take many forms, there are some key elements in all research writing. So, while you may or may not have a friend who can evaluate the technical content of your inquiry-based writing, you can still have a friend give you some feedback on the following:

- What is the research question?

- Why is that an interesting research question? If you can’t tell, offer some suggestions.

- What data did the writer collect to answer that question(s)?

- Do you feel that the writer has enough data to answer their research question? Why or why not? Do you feel that the researcher has the right kind of data to answer their research question? Why or why not?

- What is the biggest surprise in the findings? What seems to be the most important finding?

- What remains unclear to you after reading the draft?

Session overview : Now that you have a firm grounding in your self-generated research projects, the community entry point activities that follow in this module help you position yourselves within larger community responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Community-based prompts are for writers who want to advocate for a particular position and work with members of their own communities. These activities also provide a foundation for the skills, such as interviewing.

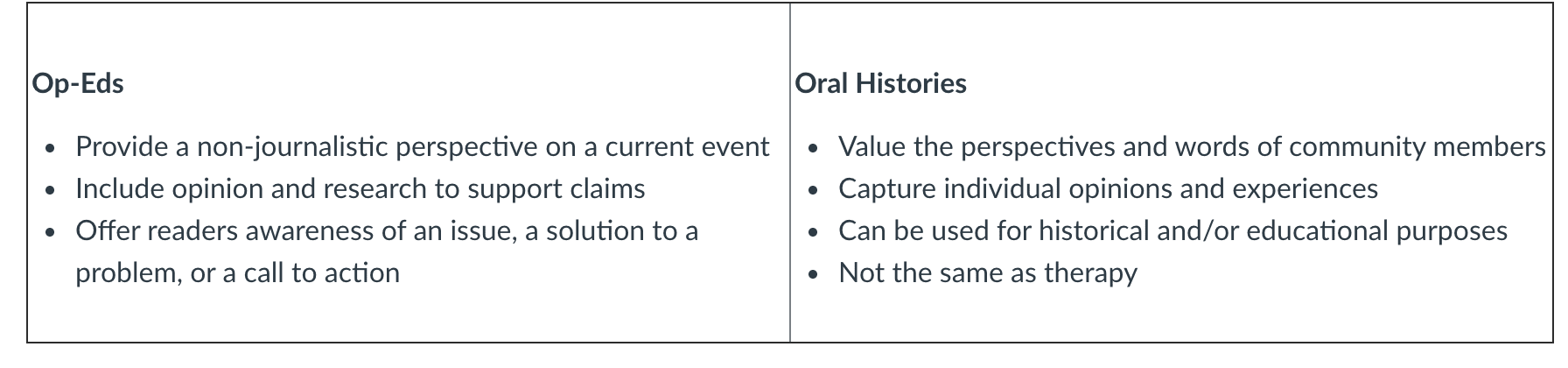

In this session, we offer participants two ways of using writing for community-based projects: op-eds and oral histories. Op-ed advice is targeted for participants who want to take their self-generated research inquiries and use their findings as means to advocate for particular positions, interventions, or recommendations. Oral history advice is for participants who want a more intimate way of using writing to advocate for community awareness by capturing the stories of community members. Activities in this session guide writers through the writing process for both of these activities. This session follows three steps:

- Identify common types of community-based writing.

- Generate op-ed pitches and trauma-informed interview questions to support public-facing narratives and oral histories.

- Draft an op-ed or transcribe an oral history interview.

- Reading: Tasha Golden, “Where Your Writing Can Go: Storytelling as Advocacy,” The Ploughshares Blog

Community-based writing values the perspectives of individuals outside the academy. That means, community members’ ideas guide the research and final product. For example, op-eds are often meant to give voice to individuals who are not professional journalists but who may have particular expertise in a topic or lived experiences that offer readers valuable perspectives. Other community-based writing projects, such as oral history projects, are meant to document people in specific locations at specific times in history.

In this session, you will gain exposure to these common types of community-based writing, including strategies for developing your ideas as well as reading published examples.

- Reading: Reann Gibson, “Communities of Color Hit Hardest by Heat Waves,” The Boston Globe

- Reading: David Lat, “Op-Ed: People ask me if I’ve recovered from COVID-19. That’s not an Easy Question to Answer,” Los Angeles Times

- Sabrina Strings, “It’s Not Obesity. It’s Slavery,” The New York Times

- Reading: “Writing OpEds That Make A Difference,” Indivisible

- Reading: Kristine Maloney, “Op-ed Writing Tips to Consider During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Inside Higher Ed

- The Op-Ed Project, “Op-Ed Writing Tips and Tricks”

- Reading: “Covid-19 Oral History Plague,” Journal of the Plague Year

- Reading: Jo Healey, “Reporting on Coronavirus: Handling Sensitive Remote Interviews,” Dart Center

- Reading: Jina Moore, “Covering Trauma, A Training Guide”

- Reading: Jina Moore, “Five Ideas on Meaningful Consent in Trauma Journalism”

- Video: Trauma-Informed Interviewing: Techniques from a Clinician’s Toolkit

In this session, you will apply the strategies from the previous section to your own writing process, clarifying your stance and audience through drafting a pitch for op-ed projects and generating interview questions for oral histories and similar narrative projects.

Use the following questions to help draft your brief pitch and begin framing your draft:

Preparing for the Op-Ed

1. Why write an op-ed? Clarify your purpose:

a. Inform (make aware of)

b. Educate (going a little deeper)

c. Persuade

e. Advocate/offer call to action

2. Basic questions to draft a pitch:

a. What’s your issue? What is the “hook” or current event that frames this piece?

b. Why right now?

c. What’s your unique perspective/recommendation within this issue? What is the counter view to this?

d. Why should you be the one to write it? (credentials, relevant life experiences, etc.)

e. Where should you pitch it? (local or national publication)

3. The argument: How are you making your case?

a. Anecdotal evidence–the personal, contextual details that engage the reader (potentially from Module 1)

b. Research–the evidence to support your recommendation or position (from Module 2)

c. Testimony–the words of others to help you make your case (from oral histories)

4. The writing:

a. Be as concise as possible (typically around 750 words)

b. Use active voice

c. Avoid clichés

d. Use specific examples

e. Have a consistent voice

f. Know your audience

Preparing to interview community members for oral histories

1. What are the goals and purpose for collecting these oral histories?

a. “To provide a historic record of what has happened and its multiple impact on individuals and within communities.

b. To share the results of these findings with professionals who make humanitarian interventions in the aftermath, and to record the success and failures of those programs if resources permit.

c. To support those who give testimony in creating narratives that through their very expressivity and creativity can help rebuild communities and reconstruct identity in the wake of the catastrophe.” (Albarelli et al., 2020, p. 13)

2. Define the frame of the project:

a. Place. Currently, most interviews should be conducted remotely.

b. Time. You must decide if you will interview someone while an event is happening, immediately after an event, or after some period of time has passed since the event.

c. People. The people you interview are called “narrators.”

d. Technology. Decide what technology you will use to conduct the interview.

e. Legal issues. Read the claim rights, if you are using professional software for interviewing.

3. Select the focus of the interviews:

a. Will you focus on a specific moment in time or an expanse of time?

b. Will you use the same questions for each narrator, same themes but varied questions, or freeform format?

c. How long will you interview a narrator?

d. Will you be seeking a second interview?

e. Will you give narrators the opportunity to listen to their interviews?

4. Develop a plan for listening and publishing interviews

a. How will you listen for accuracy of meaning?

b. How will you address awkward passages or inaudible passages in the interviews? Will you remove filler words like “uh” and “um” from the transcripts?

c. Will you trace themes across interviews and provide an analysis or build compelling profiles of individual narrators?

d. Will you select the most interesting quotes or allow the interview to be published in its entirety?

e. What will you do about interviews that did not go well?

f. How will you understand the way your perspectives might shape how you interpret the interview?

g. How might the interviews be used for unintended purposes? How might you safeguard against that happening?

5. Develop a plan for storing the interview files

a. Who owns the rights to the interviews?

b. Where can the audio or video files be stored safely so as to ensure the confidentiality of you and the narrators?

c. If you need to access the audio or video files in the future, can you do that easily?

d. If you plan on destroying unused material, how can you ensure that the information has actually been destroyed or erased?

Interviewing Community Members: Interviewing Tips

Interviewing community members who have undergone traumatic experiences requires patience, empathy, and resilience. Interviewing requires that we become witnesses to events. When those events are catastrophic or traumatic events, then we are emotionally and physically implicated in those events. Moreover, because of the difficult nature of interviewing community members who have undergone traumatic experiences, it is critical to set-out the framework for your interview before you begin asking questions.

When contacting potential community members:

- Explain the purpose of the interview and ensure that you explain the interview is voluntary. You may never coerce someone into an interview.

- Explain how the interview will happen–for example, do you plan on recording the interview? Respect narrators wishes if they do not want to be recorded or videotaped. All narrators may stop an interview at any time, if they wish.

- Explain who you are. (See self-reflexivity in Module 2)

- Explain how the interview material will be used. Will the interview be made public or kept private?

- Explain how you will ensure the safety and privacy of participants being interviewed. Will narrators’ real names be used or will they be given pseudonyms?

- Confirm the day, time, length, and format of the interview in advance.

- Explain any compensation or other benefits from the interview.

- Provide your contact information.

Good oral history interviewers (Adapted from Aras et al., p. 15):