- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

10 Successful Design Thinking Case Study

Dive into the realm of Successful Design Thinking Case Studies to explore the power of this innovative problem-solving approach. Begin by understanding What is Design Thinking? and then embark on a journey through real-world success stories. Discover valuable lessons learned from these case studies and gain insights into how Design Thinking can transform your approach.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Leadership Skills Training

- Instructional Design Training

- Design Thinking Course

- Business Development Training

- Leadership and Management Course

Design Thinking has emerged as a powerful problem-solving approach that places empathy, creativity, and innovation at the forefront. However, if you are not aware of the power that this approach holds, a Design Thinking Case Study is often used to help people address the complex challenges of this approach with a human-centred perspective. It allows organisations to unlock new opportunities and drive meaningful change. Read this blog on Design Thinking Case Study to learn how it enhances organisation’s growth and gain valuable insights on creative problem-solving.

Table of Contents

1) What is Design Thinking?

2) Design Thinking process

3) Successful Design Thinking Case Studies

a) Airbnb

b) Apple

c) Netflix

d) UberEats

e) IBM

f) OralB’s electric toothbrush

g) IDEO

h) Tesla

i) GE Healthcare

j) Nike

3) Lessons learned from Design Thinking Case Studies

4) Conclusion

What is Design Thinking ?

Before jumping on Design Thinking Case Study, let’s first understand what it is. Design Thinking is a methodology for problem-solving that prioritises the understanding and addressing of individuals' unique needs.

This human-centric approach is creative and iterative, aiming to find innovative solutions to complex challenges. At its core, Design Thinking fosters empathy, encourages collaboration, and embraces experimentation.

This process revolves around comprehending the world from the user's perspective, identifying problems through this lens, and then generating and refining solutions that cater to these specific needs. Design Thinking places great importance on creativity and out-of-the-box thinking, seeking to break away from conventional problem-solving methods.

It is not confined to the realm of design but can be applied to various domains, from business and technology to healthcare and education. By putting the user or customer at the centre of the problem-solving journey, Design Thinking helps create products, services, and experiences that are more effective, user-friendly, and aligned with the genuine needs of the people they serve.

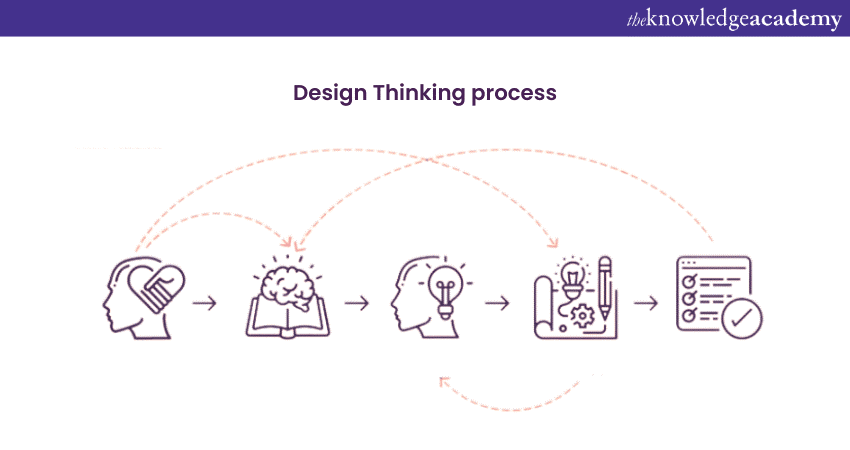

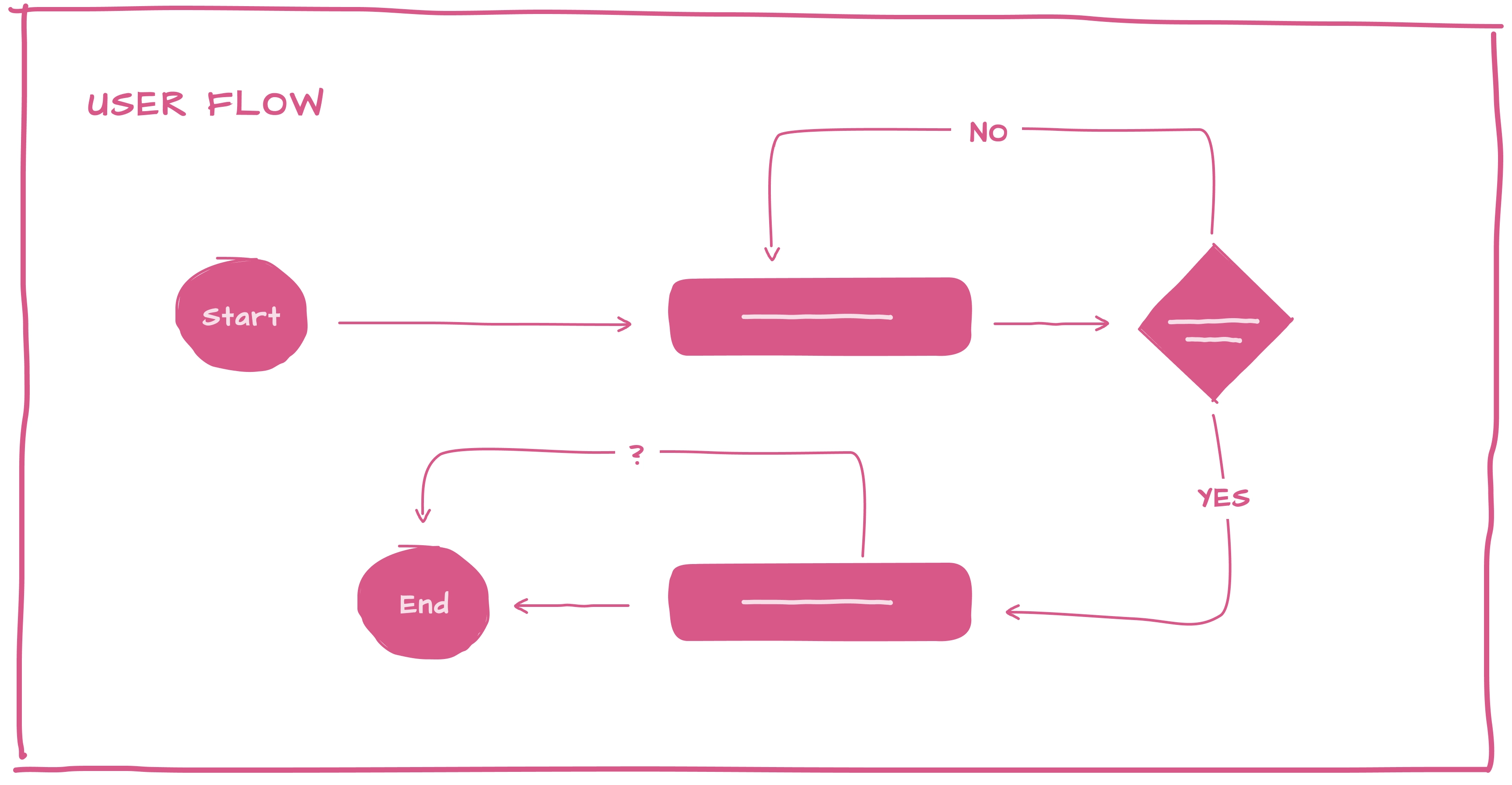

Design Thinking process

Design Thinking is a problem-solving and innovation framework that helps individuals and teams create user-centred solutions. This process consists of five key phases that are as follows:

To initiate the Design Thinking process, the first step is to practice empathy. In order to create products and services that are appealing, it is essential to comprehend the users and their requirements. What are their anticipations regarding the product you are designing? What issues and difficulties are they encountering within this particular context?

During the empathise phase, you spend time observing and engaging with real users. This might involve conducting interviews and seeing how they interact with an existing product. You should pay attention to facial expressions and body language. During the empathise phase in the Design Thinking Process , it's crucial to set aside assumptions and gain first-hand insights to design with real users in mind. That's the essence of Design Thinking.

During the second stage of the Design Thinking process, the goal is to identify the user’s problem. To accomplish this, collect all your observations from the empathise phase and begin to connect the dots.

Ask yourself: What consistent patterns or themes did you notice? What recurring user needs or challenges were identified? After synthesising your findings, you must create a problem statement, also known as a Point Of View (POV) statement, which outlines the issue or challenge you aim to address. By the end of the define stage, you will be able to craft a clear problem statement that will guide you throughout the design process, forming the basis of your ideas and potential solutions.

After completing the first two stages of the Design Thinking process, which involve defining the target users and identifying the problem statement, it is now time to move on to the third stage - ideation. This stage is all about brainstorming and coming up with various ideas and solutions to solve the problem statement. Through ideation, the team can explore different perspectives and possibilities and select the best ideas to move forward with.

During the ideation phase, it is important to create an environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their ideas without fear of judgment. This phase is all about generating a large quantity of ideas, regardless of feasibility. This is done by encouraging the team to think outside the box and explore new angles. To maximise creativity, ideation sessions are often held in unconventional locations.

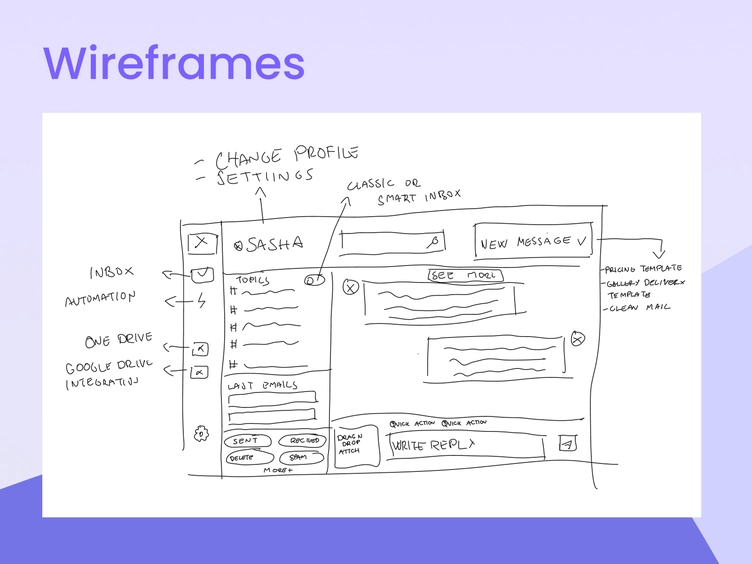

It’s time to transform the ideas from stage three into physical or digital prototypes. A prototype is a miniature model of a product or feature, which can be as simple as a paper model or as complex as an interactive digital representation.

During the Prototyping Stage , the primary objective is to transform your ideas into a tangible product that can be tested by actual users. This is crucial in maintaining a user-centric approach, as it enables you to obtain feedback before proceeding to develop the entire product. By doing so, you can ensure that the final design adequately addresses the user's problem and delivers an enjoyable user experience.

During the Design Thinking process, the fifth step involves testing your prototypes by exposing them to real users and evaluating their performance. Throughout this testing phase, you can observe how your target or prospective users engage with your prototype. Additionally, you can gather valuable feedback from your users about their experiences throughout the process.

Based on the feedback received during user testing, you can go back and make improvements to the design. It is important to remember that the Design Thinking process is iterative and non-linear. After the testing phase, it may be necessary to revisit the empathise stage or conduct additional ideation sessions before creating a successful prototype.

Unlock the power of Design Thinking – Sign up for our comprehensive Design Thinking for R&D Engineers Training Today!

Successful Design Thinking Case Studies

Now that you have a foundational understanding of Design Thinking, let's explore how some of the world's most successful companies have leveraged this methodology to drive innovation and success:

Case Study 1: Airbnb

Airbnb’s one of the popular Design Thinking Case Studies that you can aspire from. Airbnb disrupted the traditional hotel industry by applying Design Thinking principles to create a platform that connects travellers with unique accommodations worldwide. The founders of Airbnb, Brian Chesky, Joe Gebbia, and Nathan Blecharczyk, started by identifying a problem: the cost and lack of personalisation in traditional lodging.

They conducted in-depth user research by staying in their own listings and collecting feedback from both hosts and guests. This empathetic approach allowed them to design a platform that not only met the needs of travellers but also empowered hosts to provide personalised experiences.

Airbnb's intuitive website and mobile app interface, along with its robust review and rating system, instil trust and transparency, making users feel comfortable choosing from a vast array of properties. Furthermore, the "Experiences" feature reflects Airbnb's commitment to immersive travel, allowing users to book unique activities hosted by locals.

Case Study 2. Apple

Apple Inc. has consistently been a pioneer in Design Thinking, which is evident in its products, such as the iPhone. One of the best Design Thinking Examples from Apple is the development of the iPhone's User Interface (UI). The team at Apple identified the need for a more intuitive and user-friendly smartphone experience. They conducted extensive research and usability testing to understand user behaviours, pain points, and desires.

The result? A revolutionary touch interface that forever changed the smartphone industry. Apple's relentless focus on the user experience, combined with iterative prototyping and user feedback, exemplifies the power of Design Thinking in creating groundbreaking products.

Apple invests heavily in user research to anticipate what customers want before they even realise it themselves. This empathetic approach to design has led to groundbreaking innovations like the iPhone, iPad, and MacBook, which have redefined the entire industry.

Case Study 3. Netflix

Netflix, the global streaming giant, has revolutionised the way people consume entertainment content. A major part of their success can be attributed to their effective use of Design Thinking principles.

What sets Netflix apart is its commitment to understanding its audience on a profound level. Netflix recognised that its success hinged on offering a personalised, enjoyable viewing experience. Through meticulous user research, data analysis, and a culture of innovation, Netflix constantly evolves its platform. Moreover, by gathering insights on viewing habits, content preferences, and even UI, the company tailors its recommendations, search algorithms, and original content to captivate viewers worldwide.

Furthermore, Netflix's iterative approach to Design Thinking allows it to adapt quickly to shifting market dynamics. This agility proved crucial when transitioning from a DVD rental service to a streaming platform. Netflix didn't just lead this revolution; it shaped it by keeping users' desires and behaviours front and centre. Netflix's commitment to Design Thinking has resulted in a highly user-centric platform that keeps subscribers engaged and satisfied, ultimately contributing to its global success.

Case Study 4. Uber Eats

Uber Eats, a subsidiary of Uber, has disrupted the food delivery industry by applying Design Thinking principles to enhance user experiences and create a seamless platform for food lovers and restaurants alike.

One of UberEats' key innovations lies in its user-centric approach. By conducting in-depth research and understanding the pain points of both consumers and restaurant partners, they crafted a solution that addresses real-world challenges. The user-friendly app offers a wide variety of cuisines, personalised recommendations, and real-time tracking, catering to the diverse preferences of customers.

Moreover, UberEats leverages technology and data-driven insights to optimise delivery routes and times, ensuring that hot and fresh food reaches customers promptly. The platform also empowers restaurant owners with tools to efficiently manage orders, track performance, and expand their customer base.

Case Study 5 . IBM

IBM is a prime example of a large corporation successfully adopting Design Thinking to drive innovation and transform its business. Historically known for its hardware and software innovations, IBM recognised the need to evolve its approach to remain competitive in the fast-paced technology landscape.

IBM's Design Thinking journey began with a mission to reinvent its enterprise software solutions. The company transitioned from a product-centric focus to a user-centric one. Instead of solely relying on technical specifications, IBM started by empathising with its customers. They started to understand customer’s pain points, and envisioning solutions that genuinely addressed their needs.

One of the key elements of IBM's Design Thinking success is its multidisciplinary teams. The company brought together designers, engineers, marketers, and end-users to collaborate throughout the product development cycle. This cross-functional approach encouraged diverse perspectives, fostering creativity and innovation.

IBM's commitment to Design Thinking is evident in its flagship projects such as Watson, a cognitive computing system, and IBM Design Studios, where Design Thinking principles are deeply embedded into the company's culture.

Elevate your Desing skills in Instructional Design – join our Instructional Design Training Course now!

Case Study 6. Oral-B’s electric toothbrush

Oral-B, a prominent brand under the Procter & Gamble umbrella, stands out as a remarkable example of how Design Thinking can be executed in a seemingly everyday product—Electric toothbrushes. By applying the Design Thinking approach, Oral-B has transformed the world of oral hygiene with its electric toothbrushes.

Oral-B's journey with Design Thinking began by placing the user firmly at the centre of their Product Development process. Through extensive research and user feedback, the company gained invaluable insights into oral care habits, preferences, and pain points. This user-centric approach guided Oral-B in designing electric toothbrushes that not only cleaned teeth more effectively but also made the entire oral care routine more engaging and enjoyable.

Another of Oral-B's crucial innovations is the integration of innovative technology into their toothbrushes. These devices now come equipped with features like real-time feedback, brushing timers, and even Bluetooth connectivity to sync with mobile apps. By embracing technology and user-centric design, Oral-B effectively transformed the act of brushing teeth into an interactive and informative experience. This has helped users maintain better oral hygiene.

Oral-B's success story showcases how Design Thinking, combined with a deep understanding of user needs, can lead to significant advancements, ultimately improving both the product and user satisfaction.

Case Study 7. IDEO

IDEO, a Global Design Consultancy, has been at the forefront of Design Thinking for decades. They have worked on diverse projects, from creating innovative medical devices to redesigning public services.

One of their most notable Design Thinking examples is the development of the "DeepDive" shopping cart for a major retailer. IDEO's team spent weeks observing shoppers, talking to store employees, and prototyping various cart designs. The result was a cart that not only improved the shopping experience but also increased sales. IDEO's human-centred approach, emphasis on empathy, and rapid prototyping techniques demonstrate how Design Thinking can drive innovation and solve real-world problems.

Upgrade your creativity skills – register for our Creative Leader Training today!

Case Study 8 . Tesla

Tesla, led by Elon Musk, has redefined the automotive industry by applying Design Thinking to Electric Vehicles (EVs). Musk and his team identified the need for EVs to be not just eco-friendly but also desirable. They focused on designing EVs that are stylish, high-performing, and technologically advanced. Tesla's iterative approach, rapid prototyping, and constant refinement have resulted in groundbreaking EVs like the Model S, Model 3, and Model X.

From the minimalist interior of their Model S to the autopilot self-driving system, every aspect is meticulously crafted with the end user in mind. The company actively seeks feedback from its user community, often implementing software updates based on customer suggestions. This iterative approach ensures that Tesla vehicles continually evolve to meet and exceed customer expectations .

Moreover, Tesla's bold vision extends to sustainable energy solutions, exemplified by products like the Powerwall and solar roof tiles. These innovations showcase Tesla's holistic approach to Design Thinking, addressing not only the automotive industry's challenges but also contributing to a greener, more sustainable future.

Case Study 9. GE Healthcare

GE Healthcare is a prominent player in the Healthcare industry, renowned for its relentless commitment to innovation and design excellence. Leveraging Design Thinking principles, GE Healthcare has consistently pushed the boundaries of medical technology, making a significant impact on patient care worldwide.

One of the key areas where GE Healthcare has excelled is in the development of cutting-edge medical devices and diagnostic solutions. Their dedication to user-centred design has resulted in devices that are not only highly functional but also incredibly intuitive for healthcare professionals to operate. For example, their advanced Medical Imaging equipment, such as MRI and CT scanners, are designed with a focus on patient comfort, safety, and accurate diagnostics. This device reflects the company's dedication to improving healthcare outcomes.

Moreover, GE Healthcare's commitment to design extends beyond the physical product. They have also ventured into software solutions that facilitate data analysis and Patient Management. Their user-friendly software interfaces and data visualisation tools have empowered healthcare providers to make more informed decisions, enhancing overall patient care and treatment planning.

Case Study 10. Nike

Nike is a global powerhouse in the athletic apparel and Footwear industry. Nike's journey began with a simple running shoe, but its design-thinking approach transformed it into an iconic brand.

Nike's Design Thinking journey started with a deep understanding of athletes' needs and desires. They engaged in extensive user research, often collaborating with top athletes to gain insights that inform their product innovations. This customer-centric approach allowed Nike to develop ground breaking technologies, such as Nike Air and Flyknit, setting new standards in comfort, performance, and style.

Beyond product innovation, Nike's brand identity itself is a testament to Design Thinking. The iconic Swoosh logo, created by Graphic Designer Carolyn Davidson, epitomises simplicity and timelessness, reflecting the brand's ethos.

Nike also excels in creating immersive retail experiences, using Design Thinking to craft spaces that engage and inspire customers. Their flagship stores around the world are showcases of innovative design, enhancing the overall brand perception.

Lessons learned from Design Thinking Case Studies

The Design Thinking process, as exemplified by the success stories of IBM, Netflix, Apple, and Nike, offers valuable takeaways for businesses of all sizes and industries. Here are three key lessons to learn from these Case Studies:

1) Consider the b ig p icture

Design Thinking encourages organisations to zoom out and view the big picture. It's not just about solving a specific problem but understanding how that problem fits into the broader context of user needs and market dynamics. By taking a holistic approach, you can identify opportunities for innovation that extend beyond immediate challenges. IBM's example, for instance, involved a comprehensive evaluation of their clients' journeys, leading to more impactful solutions.

2) Think t hrough a lternative s olutions

One of the basic principles of Design Thinking is ideation, which emphasises generating a wide range of creative solutions. Netflix's success in content recommendation, for instance, came from exploring multiple strategies to enhance user experience. When brainstorming ideas and solutions, don't limit yourself to the obvious choices. Encourage diverse perspectives and consider unconventional approaches that may lead to breakthrough innovations.

3) Research e ach c ompany’s c ompetitors

Lastly, researching competitors is essential for staying competitive. Analyse what other companies in your industry are doing, both inside and outside the realm of Design Thinking. Learn from their successes and failures. GE Healthcare, for example, leveraged Design Thinking to improve medical equipment usability, giving them a competitive edge. By researching competitors, you can gain insights that inform your own Design Thinking initiatives and help you stand out in the market.

Incorporating these takeaways into your approach to Design Thinking can enhance your problem-solving capabilities, foster innovation, and ultimately lead to more successful results.

Conclusion

Design Thinking is not limited to a specific industry or problem domain; it is a versatile approach that promotes innovation and problem-solving in various contexts. In this blog, we've examined successful Design Thinking Case Studies from industry giants like IBM, Netflix, Apple, Airbnb, Uber Eats, and Nike. These companies have demonstrated that Design Thinking is a powerful methodology that can drive innovation, enhance user experiences, and lead to exceptional business success.

Start your journey towards creative problem-solving – register for our Design Thinking Training now!

Frequently Asked Questions

Design Thinking Case Studies align with current market demands and user expectations by showcasing practical applications of user-centric problem-solving. These Studies highlight the success of empathetic approaches in meeting evolving customer needs.

By analysing various real-world examples, businesses can derive vital insights into dynamic market trends, creating innovative solutions, and enhancing user experiences. Design Thinking's emphasis on iterative prototyping and collaboration resonates with the contemporary demand for agility and adaptability.

Real-world examples of successful Design Thinking implementations can be found in various sources. For instance, you can explore several Case Study repositories on Design Thinking platforms like IDEO and Design Thinking Institute. Furthermore, you can also look for business publications, such as the Harvard Business Review as well as Fast Company, which often feature articles on successful Design Thinking applications.

The Knowledge Academy takes global learning to new heights, offering over 30,000 online courses across 490+ locations in 220 countries. This expansive reach ensures accessibility and convenience for learners worldwide.

Alongside our diverse Online Course Catalogue , encompassing 17 major categories, we go the extra mile by providing a plethora of free educational Online Resources like News updates, blogs, videos, webinars, and interview questions. Tailoring learning experiences further, professionals can maximise value with customisable Course Bundles of TKA .

The Knowledge Academy’s Knowledge Pass , a prepaid voucher, adds another layer of flexibility, allowing course bookings over a 12-month period. Join us on a journey where education knows no bounds.

The Knowledge Academy offers various Leadership Training Courses , including Leadership Skills Training, Design Thinking Course, and Creative and Analytical Thinking Training. These courses cater to different skill levels, providing comprehensive insights into Leadership Training methodologies.

Our Leadership Training blogs covers a range of topics related to Design Thinking, offering valuable resources, best practices, and industry insights. Whether you are a beginner or looking to advance your Design Thinking skills, The Knowledge Academy's diverse courses and informative blogs have you covered.

Upcoming Business Skills Resources Batches & Dates

Fri 4th Oct 2024

Fri 6th Dec 2024

Fri 14th Feb 2025

Fri 16th May 2025

Fri 25th Jul 2025

Fri 29th Aug 2025

Fri 10th Oct 2025

Fri 28th Nov 2025

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest summer sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- ISO 9001 Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

Limited Time Offer! Save up to 50% Off annual plans.* View Plans

Save up to 50% Now .* View Plans

How To Write A Case Study For Your Design Portfolio

Case studies are an important part of any designer’s portfolio. Read this article to learn everything you need to know to start writing the perfect case study.

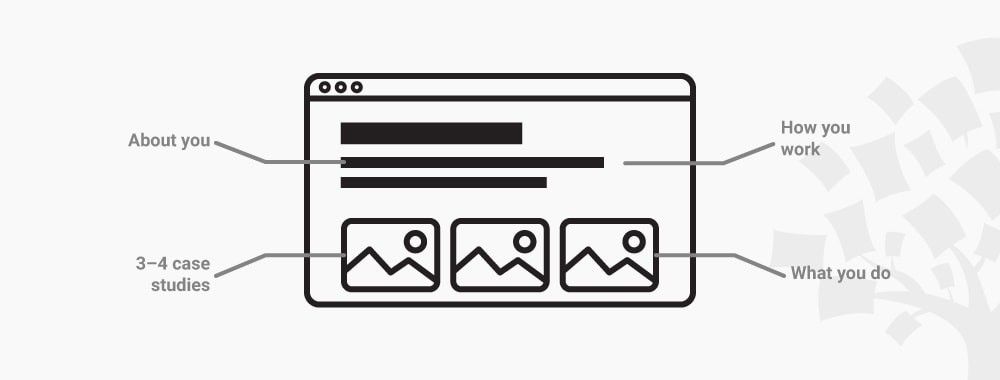

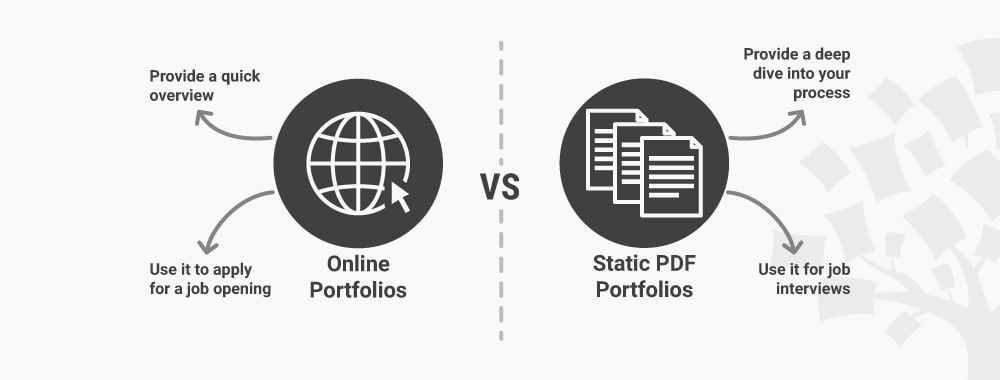

When you’re putting together your online design portfolio , design case studies are a great way to showcase your experience and skills. They also give potential clients a window into how you work.

By showing off what you can do and your design process, case studies can help you land more clients and freelance design jobs —so it can be smart to dedicate an entire section of your online portfolio website to case studies.

Getting Started

So—what is a design case study and how do they fit in your portfolio.

Let’s get some definitions out of the way first, shall we? A design case study is an example of a successful project you’ve completed. The exact case study format can vary greatly depending on your style and preferences, but typically it should outline the problem or assignment, show off your solution, and explain your approach.

One of the best ways to do that is to use a case study design that’s similar to a magazine article or long-form web article with lots of images throughout. When building your case study portfolio, create a new page for each case study. Then create a listing of all your case studies with an image and link to each of them. Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of creating these case studies.

Choose Your Best Projects

To make your online portfolio the best it can be , it’s good to be picky when choosing projects for case studies. Since your portfolio will often act as your first impression with potential clients, you only want it to showcase your best work.

If you have a large collection of completed projects, you may have an urge to do a ton of case studies. There’s an argument to be made in favor of that, since it’s a way to show off your extensive experience. In addition, by including a wide variety of case studies, it’s more likely that potential clients will be able to find one that closely relates to their business or upcoming project.

But don’t let your desire to have many case studies on your portfolio lead you to include projects you’re not as proud of. Keep in mind that your potential clients are probably busy people, so you shouldn’t expect them to wade through a massive list of case studies. If you include too many, you can never be sure which ones potential clients will take a look at. As a result, they may miss out on seeing some of your best work.

There’s no hard-and-fast rule for how many case studies to include. It’ll depend on the amount of experience you have, and how many of your completed projects you consider to be among your best work.

Use Your Design Expertise

When creating the case study section of your portfolio, use your designer’s eye to make everything attractive and easily digestible. One important guideline is to choose a layout that will enable you to include copy and image captions throughout.

Don’t have your portfolio up and running yet and not sure which portfolio platform is best for you? Try one that offers a free trial and a variety of cool templates that you can play around with to best showcase your design case studies.

If you don’t provide context for every image you include, it can end up looking like just a (somewhat confusing) image gallery. Case studies are more than that—they should explain everything that went into what you see in the images.

Check Out Other Case Study Examples for Inspiration

Looking at case study examples from successful designers is a great way to get ideas for making your case study portfolio more effective. Pay special attention to the case study design elements, including the layout, the number of images, and amount of copy. This will give you a better idea of how the designer keeps visitors interested in the story behind their projects.

To see some great case study examples, check out these UX designer portfolios .

Try a Case Study Template

There are plenty of resources online that offer free case study templates . These templates can be helpful, as they include questions that’ll help you ensure you’ve included all the important information.

However, most of them are not tailored to designers. These general case study templates don’t have the formatting you’ll want (i.e. the ability to include lots of images). Even the ones that are aimed at designers aren’t as effective as creating your own design. That’s why case study templates are best used as a starting point to get you thinking, or as a checklist to ensure you’ve included everything.

How to Write Case Studies

Maintain your usual tone.

You should write your case studies in the same personal, authentic (yet still professional!) tone of voice as you would when creating the About Me section of your portfolio . Don’t get bogged down in too much technical detail and jargon—that will make your case studies harder to read.

Since your case studies are part of your online portfolio, changing your usual tone can be jarring to the reader.

Instead, everything on your portfolio should have a consistent style. This will help you with creating brand identity . The result will be potential clients will be more connected to your writing and get the feeling that they’re learning what makes you unique.

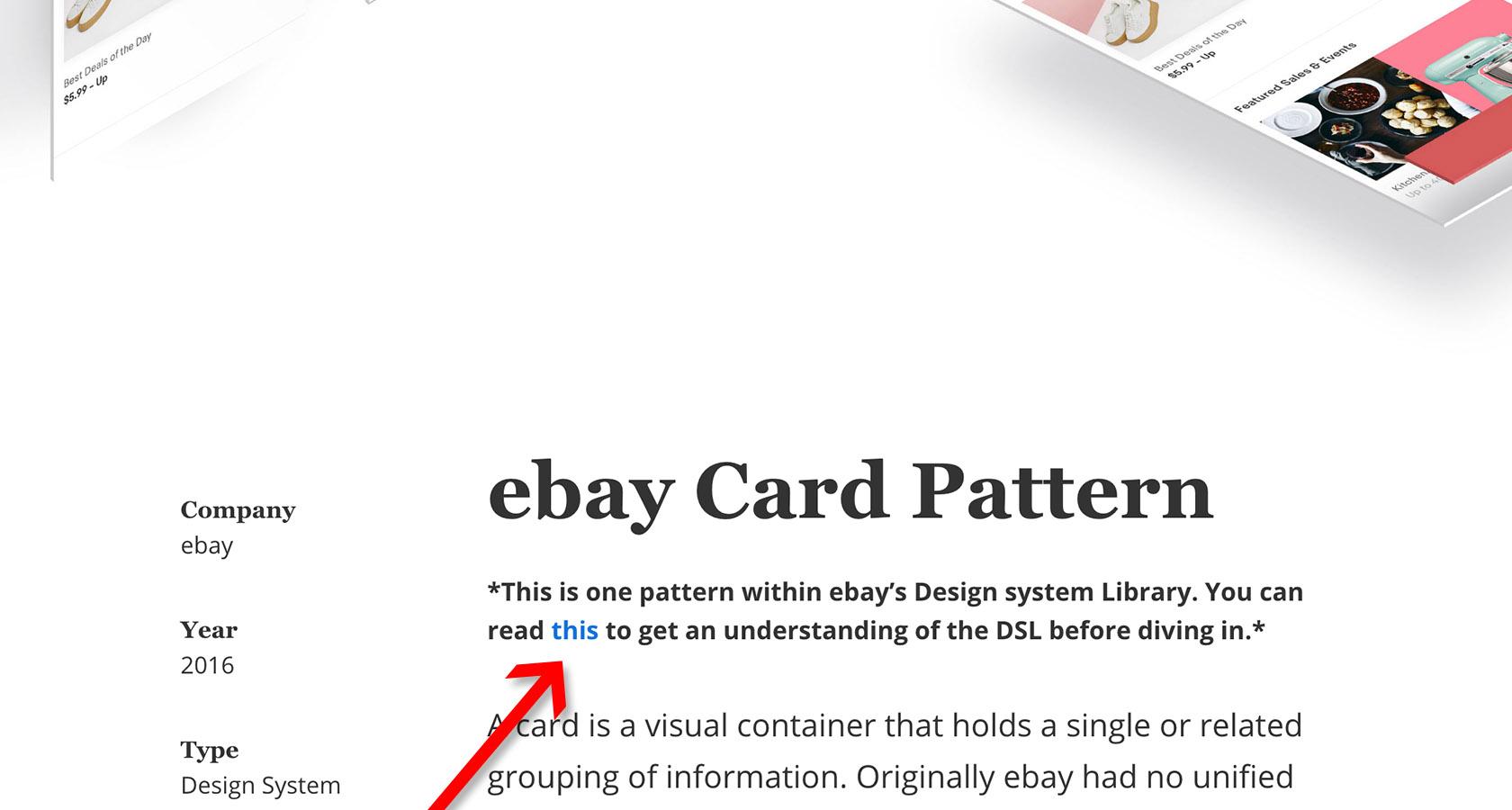

Provide Some Context

Case studies are more effective when you include some information at the beginning to set the stage. This can include things like the date of the project, name of the client, and what the client does. Providing some context will make the case study more relatable to potential clients.

Also, by including the date of the project, you can highlight how your work has progressed over time. However, you don’t want to bog down this part of the case study with too much information. So it only really needs to be a sentence or two.

Explain the Client’s Expectations

Another important piece of information to include near the beginning of your case study is what the client wanted to accomplish with the project. Consider the guidelines the client provided, and what they would consider a successful outcome.

Did this project involve unique requirements? Did you tailor the design to suit the client’s brand or target audience? Did you have to balance some conflicting requirements?

Establishing the client’s expectations early on in the case study will help you later when you want to explain how you made the project a success.

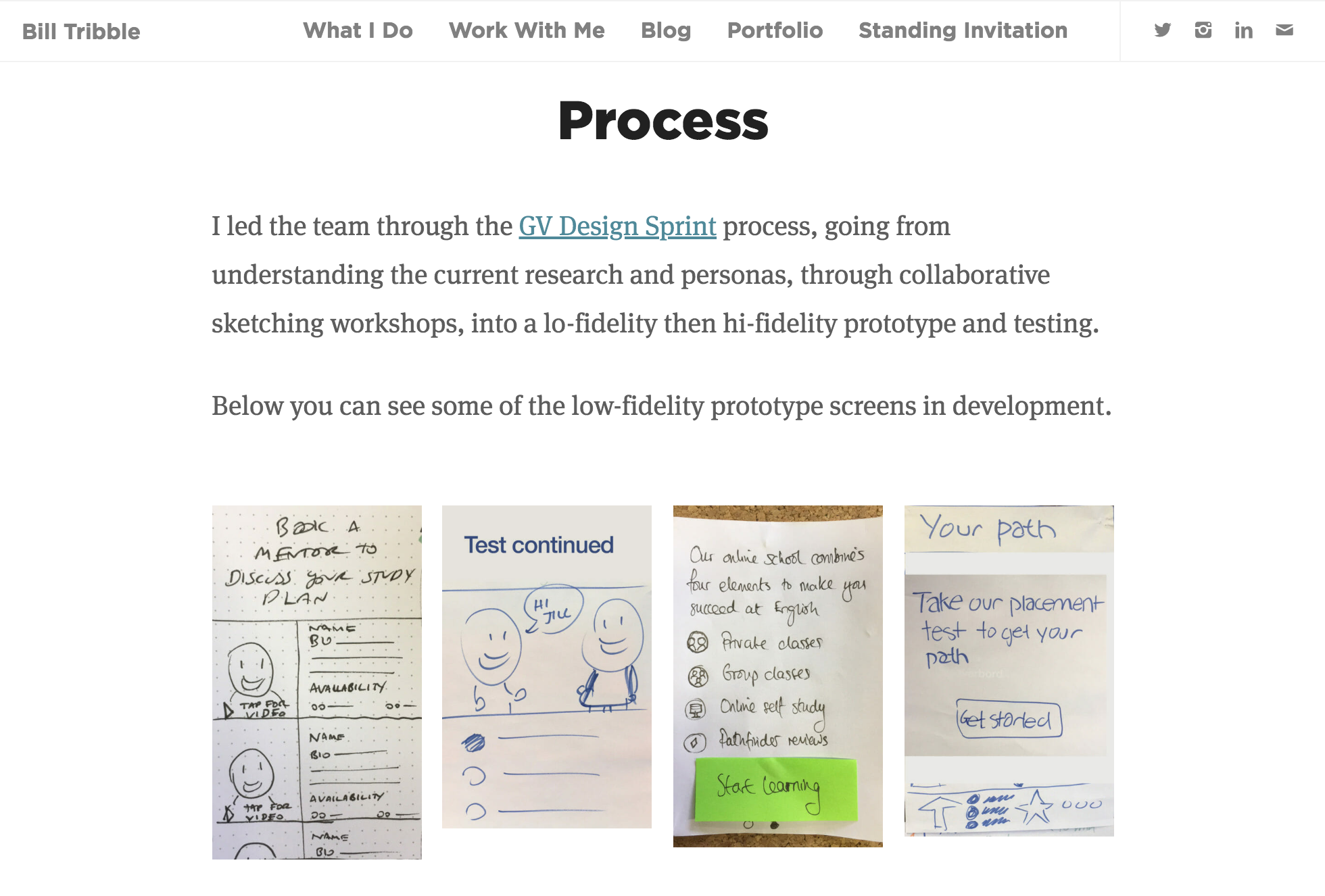

Document Your Design Process

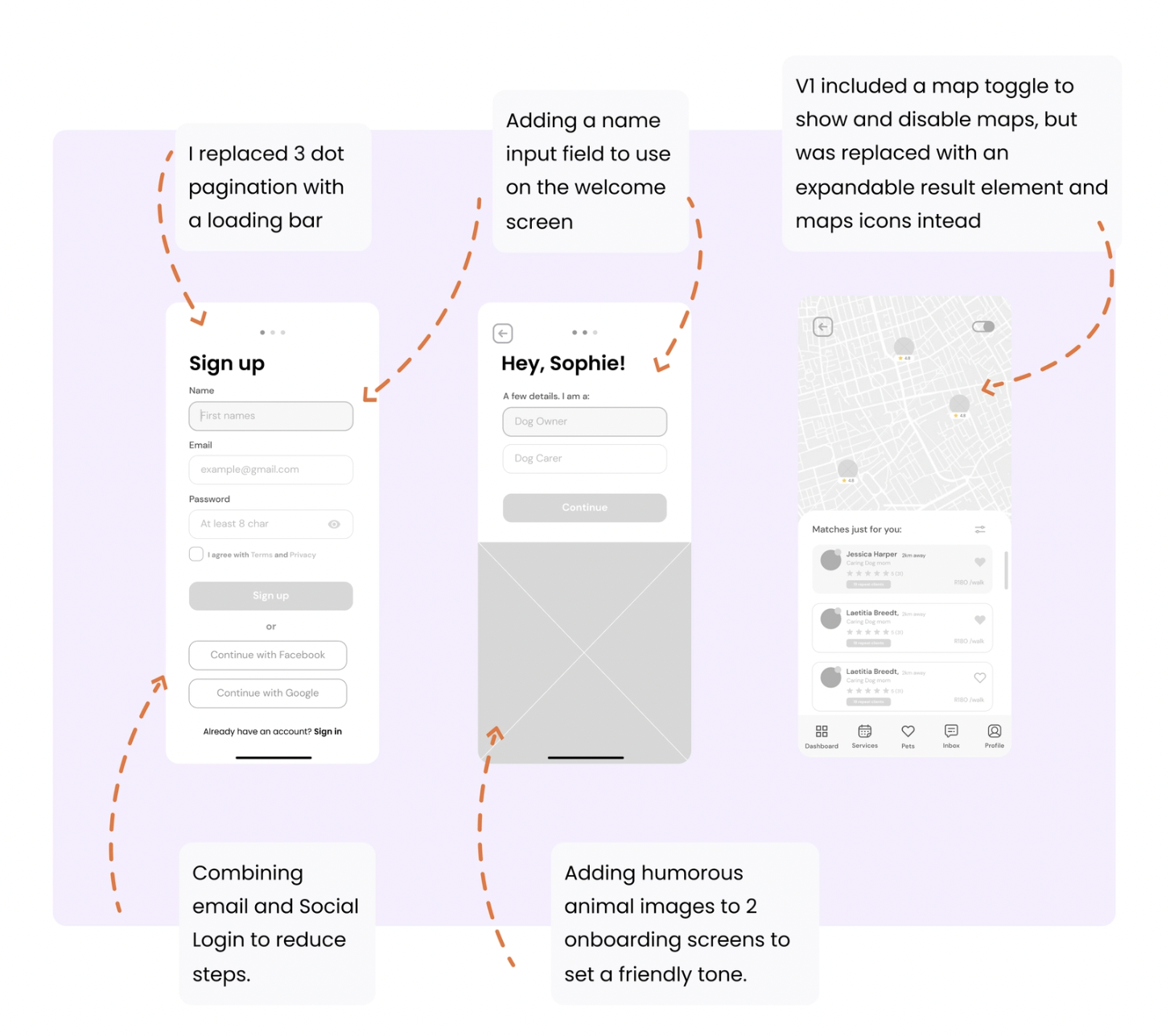

As you write your case study, you should take a look at your process from an outsider’s point of view. You already know why you made the decisions you did, so it may feel like you’re explaining the obvious. But by explaining your thought process, the case study will highlight all the consideration you put into the design project.

This can include everything from your initial plan to your inspiration, and the changes you made along the way. Basically, you should think about why you took the approach you did, and then explain it.

At this point, consider mentioning any tricks you use to make your design process more efficient . That can include how you managed your time, how you communicated with clients, and how you kept things on track.

Don’t Be Afraid to Mention Challenges

When writing a case study, it can be tempting to only explain the parts that went flawlessly. But you should consider mentioning any challenges that popped up along the way.

Was this project assigned with an extremely tight deadline? Did you have to ask the client to clarify their desired outcome? Were there revisions requested?

If you have any early drafts or drawings from the project saved, it can be a good idea to include them in the case study as well—even if they show that you initially had a very different design in mind than you ended up with. This can show your flexibility and willingness to go in new directions in order to achieve the best results.

Mentioning these challenges is another opportunity to highlight your value as a designer to potential clients. It will give you a chance to explain how you overcame those challenges and made the project a success.

Show How the Project’s Success Was Measured

Case studies are most engaging when they’re written like stories. If you followed the guidelines in this article, you started by explaining the assignment. Next, you described the process you went through when working on it. Now, conclude by going over how you know the project was a success.

This can include mentioning that all of the client’s guidelines were met, and explaining how the design ended up being used.

Check if you still have any emails or communications with the client about their satisfaction with the completed project. This can help put you in the right mindset for hyping up the results. You may even want to include a quote from the client praising your work.

Start Writing Your Case Studies ASAP

Since case studies involve explaining your process, it’s best to do them while the project is still fresh in your mind. That may sound like a pain; once you put a project to bed, you’re probably not looking forward to doing more work on it. But if you get started on your case study right away, it’s easier to remember everything that went into the design project, and why you made the choices you did.

If you’re just starting writing your case studies for projects you’ve completed in the past, don’t worry. It will just require a couple more steps, as you may need to refresh your memory a bit.

Start by taking a look at any emails or assignment documents that show what the client requested. Reviewing those guidelines will make it easier to know what to include in your case study about how you met all of the client’s expectations.

Another helpful resource is preliminary drafts, drawings, or notes you may have saved. Next, go through the completed project and remind yourself of all the work that went into achieving that final design.

Draw Potential Clients to See Your Case Studies

Having a great portfolio is the key to getting hired . By adding some case studies to your design portfolio, you’ll give potential clients insight into how you work, and the value you can offer them.

But it won’t do you any good if they don’t visit your portfolio in the first place! Luckily, there are many ways you can increase your chances. One way is to add a blog to your portfolio , as that will improve your site’s SEO and draw in visitors from search results. Another is to promote your design business using social media . If you’re looking to extend your reach further, consider investing in a Facebook ad campaign , as its likely easier and less expensive than you think.

Once clients lay eyes on all your well-written, beautifully designed case studies, the work will come roaring in!

Want to learn more about creating the perfect design portfolio? 5 Designers Reveal How to Get Clients With Your Portfolio 20 Design Portfolios You Need to See for Inspiration Study: How Does the Quality of Your Portfolio Site Influence Getting Hired?

A Guide to Improving Your Photography Skills

Elevate your photography with our free resource guide. Gain exclusive access to insider tips, tricks, and tools for perfecting your craft, building your online portfolio, and growing your business.

Get the best of Format Magazine delivered to your inbox.

Kickback Youths Photograph Canada Basketball Nationals: Spotlight on the Next Generation of Sports Photographers

Enter the Booooooom Illustration Awards: Supported by Format

Format Portfolio 2024 Prizewinner in Partnership with SAE’s Creative Media Institute

The Art Auction for Old Growth: Artists Impacting Environmental Change

Tips on Building Impactful Architectural Portfolios with Format

Winners Announced: Format Online Portfolio Giveaway in Partnership with BWP

How to Edit an Impactful Montage Reel for Your Portfolio That Highlights Your Skill

21 Essential Design Blogs to Spark Your Creativity in 2024

*Offer must be redeemed by September 30th , 2024 at 11:59 p.m. PST. 50% discount off the subscription price of a new annual Pro Plus plan can be applied at checkout with code PROPLUSANNUAL, 38% discount off the price of a new annual Pro plan can be applied with code PROANNUAL, and 20% discount off the price of a new Basic annual plan can be applied with code BASICANNUAL. The discount applies to the first year only. Cannot be combined with any other promotion.

- UI Designers

- UX Designers

- Creative Directors

- Web Designers

- Mobile App Designers

- Visual Designers

- Product Designers

- Responsive Web Designers

All About Process: Dissecting Case Study Portfolios

A portfolio is more than a cache of images, it’s a way to demonstrate design skills and problem solving to clients. We show how to elevate portfolios by explaining the inner workings of a case study.

By Adnan Puzic

Adnan is a UI/UX expert with a bold aesthetic and a passion for designing digital products for startups and corporations.

PREVIOUSLY AT

Designers have portfolios. It’s a precondition of our profession. We all know we need one, so we get to work assembling images and writing project descriptions. Then, we put our work on the web for all to see, tiny shrines to individual talent and creativity.

It’s a familiar process, a rite of passage, but why do we need portfolios in the first place?

If we’re honest, we must admit that most of our portfolio design decisions are influenced by what other designers are doing. That’s not necessarily bad, but if we don’t understand why portfolios look the way they do, we’re merely imitating.

We may produce dazzling imagery, but we also risk a portfolio experience that’s like strolling through an art gallery. “Look at the pretty pictures…”

The number one audience that design portfolios must please? Non-designers.

These are the people who seek our services, the ones working for the businesses and organizations that invest in our problem solving abilities.

Non-designers need more than beauty from a design portfolio; they need clarity and assurance. They need to come away believing in a designer’s expertise, their design process, and ability to solve problems in an efficient manner.

Luckily, it’s not difficult to design a portfolio to meet those needs.

The Advantages of a Case Study

What is a case study?

A case study is a tool that a designer may use to explain his involvement in a design project, whether as a solo designer or part of a team. It is a detailed account, written in the designer’s own voice (first person), that examines the client’s problem, the designer’s role, the problem solving process, and the project’s outcome.

Who can use a case study?

The beauty of the case study framework is that it’s adaptable to multiple design disciplines. It organizes need-to-know information around common categories and questions that are applicable to all kinds of design projects—from UX research to visual identities .

At its core, a case study is a presentation format for communicating the journey from problem to solution. Details within the framework may change, but the momentum is always moving towards clarity and uncovering a project’s most important whats , whys , and hows .

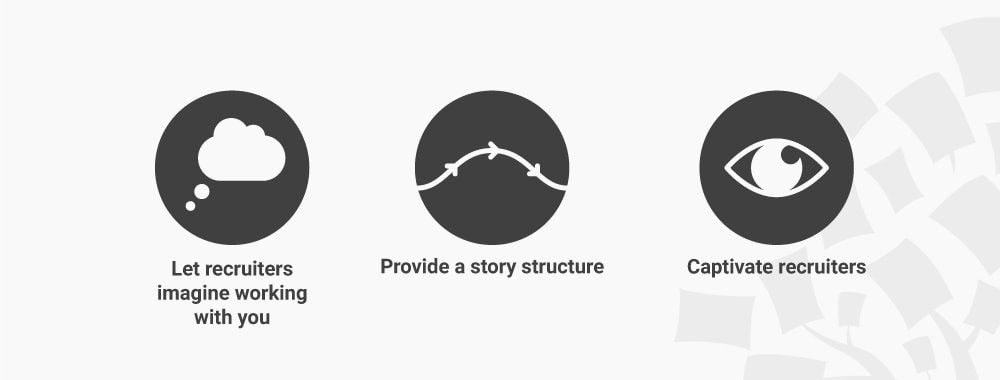

How do case studies benefit designers?

Many clients don’t understand all that goes into the design process. And while they certainly don’t need to know everything , a case study provides a big-picture overview and sets up realistic expectations about what it takes to design an elegant solution.

A case study can also be a handy presentation aide that a designer may use when interviewing a potential client. The format allows a designer to talk about their work and demonstrate their expertise in a natural and logical progression. “Here’s what I did, how it helped, and how I might apply a similar approach with you.”

Are there any drawbacks to using case studies?

Don’t let a case study turn into a ca-a-a-a-a-se study. The whole project should be digestible within 1-2 minutes max. If necessary, provide links to more detailed documents so that interested visitors may explore further.

A lot of design work, especially digital, is created within multidisciplinary teams, so designers need to be clear about their role in a project. Blurring the lines of participation gives clients false expectations.

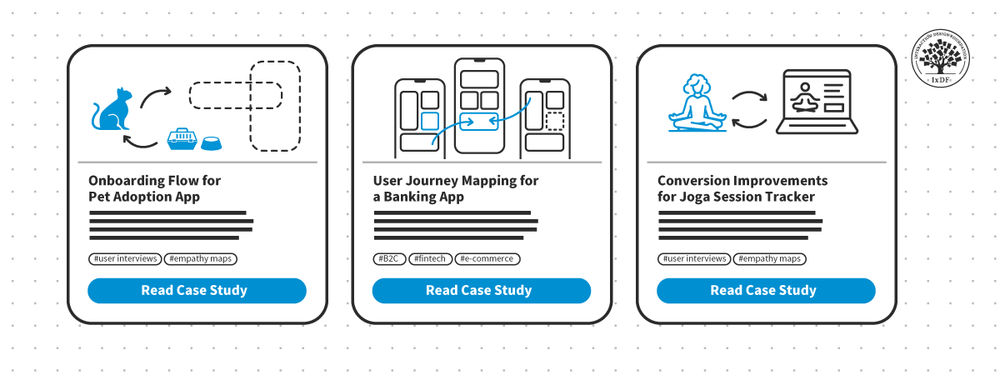

Many make the mistake of treating portfolios as repositories of all of their past projects, but three to five case studies documenting a designer’s most outstanding work is enough to satisfy the curiosity of most potential clients (who simply don’t have time to mine through everything a designer ever did).

Case studies are professional documents, not tell-all manuscripts, and there are some things that simply shouldn’t be included. Descriptions of difficult working relationships, revelations of company-specific information (i.e., intellectual property), and contentious explanations of rejected ideas ought to be left out.

Crafting a Customer-centric Case Study

It’s one thing to know what a case study is and why it’s valuable. It’s an entirely different and more important thing to know how to craft a customer-centric case study. There are essentials that every case study must include if clients are to make sense of what they’re seeing.

What are the core elements of a case study?

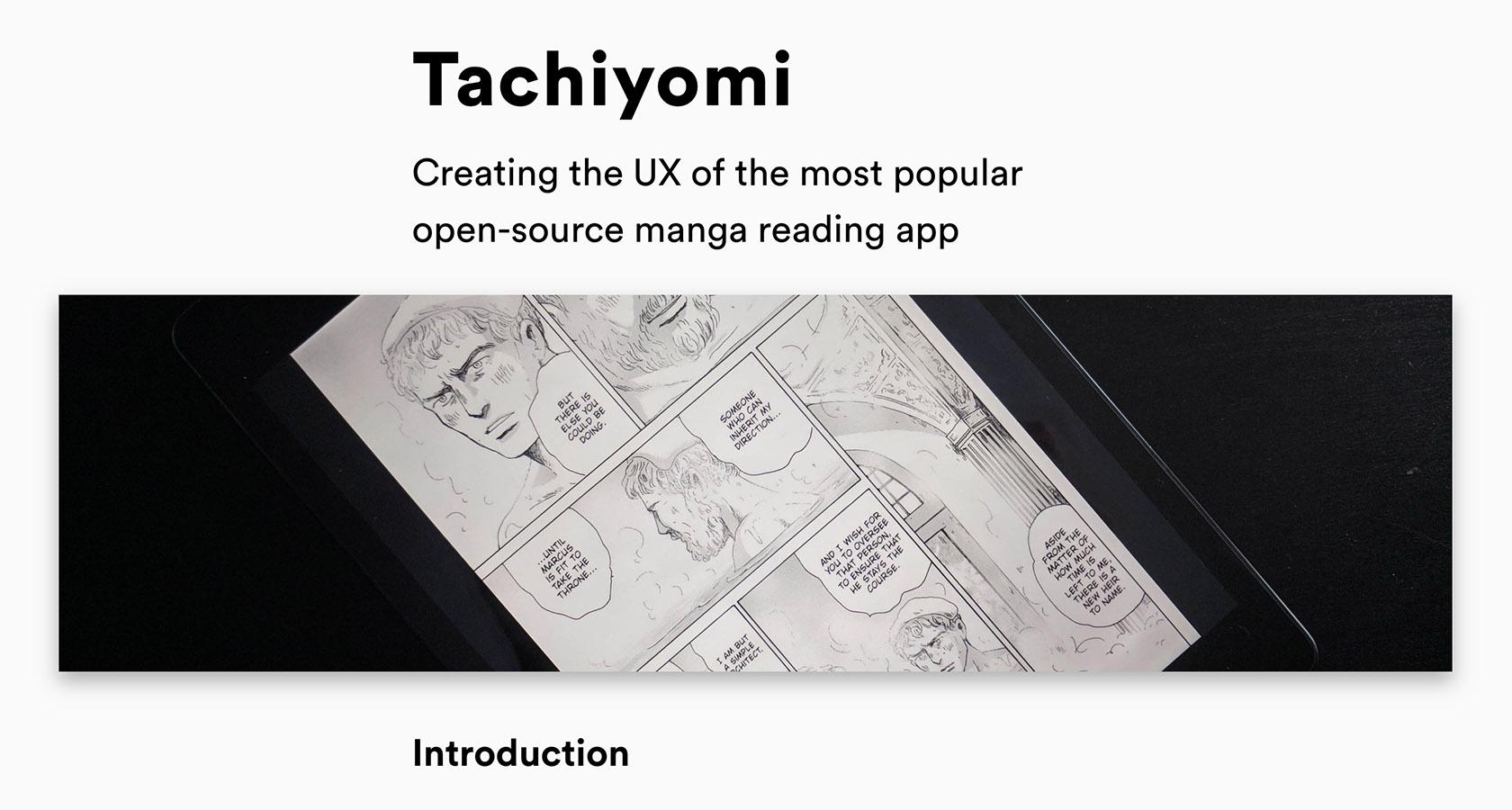

Introduce the client.

Present the design problem.

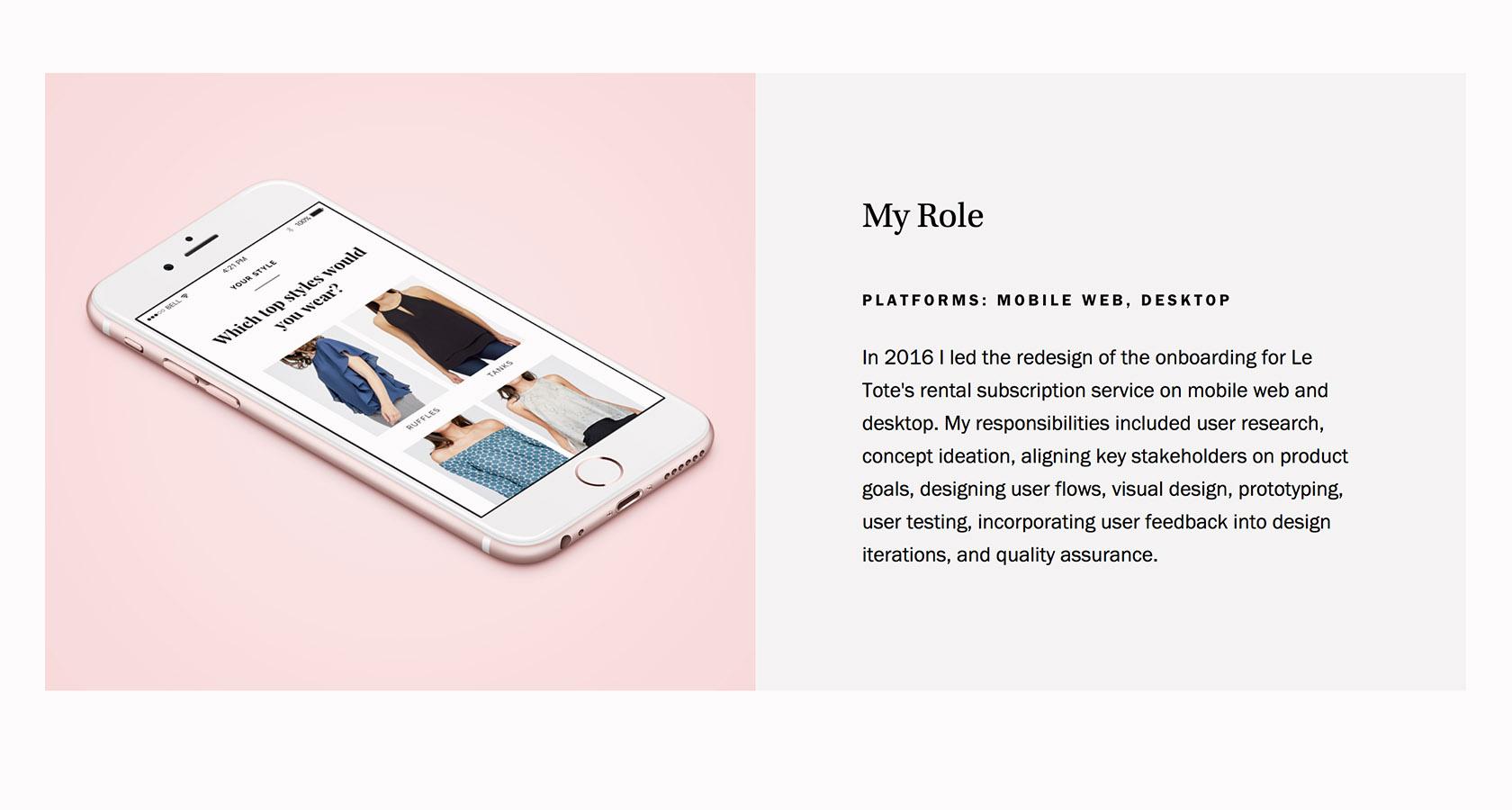

Recap your role.

Share the solution you designed.

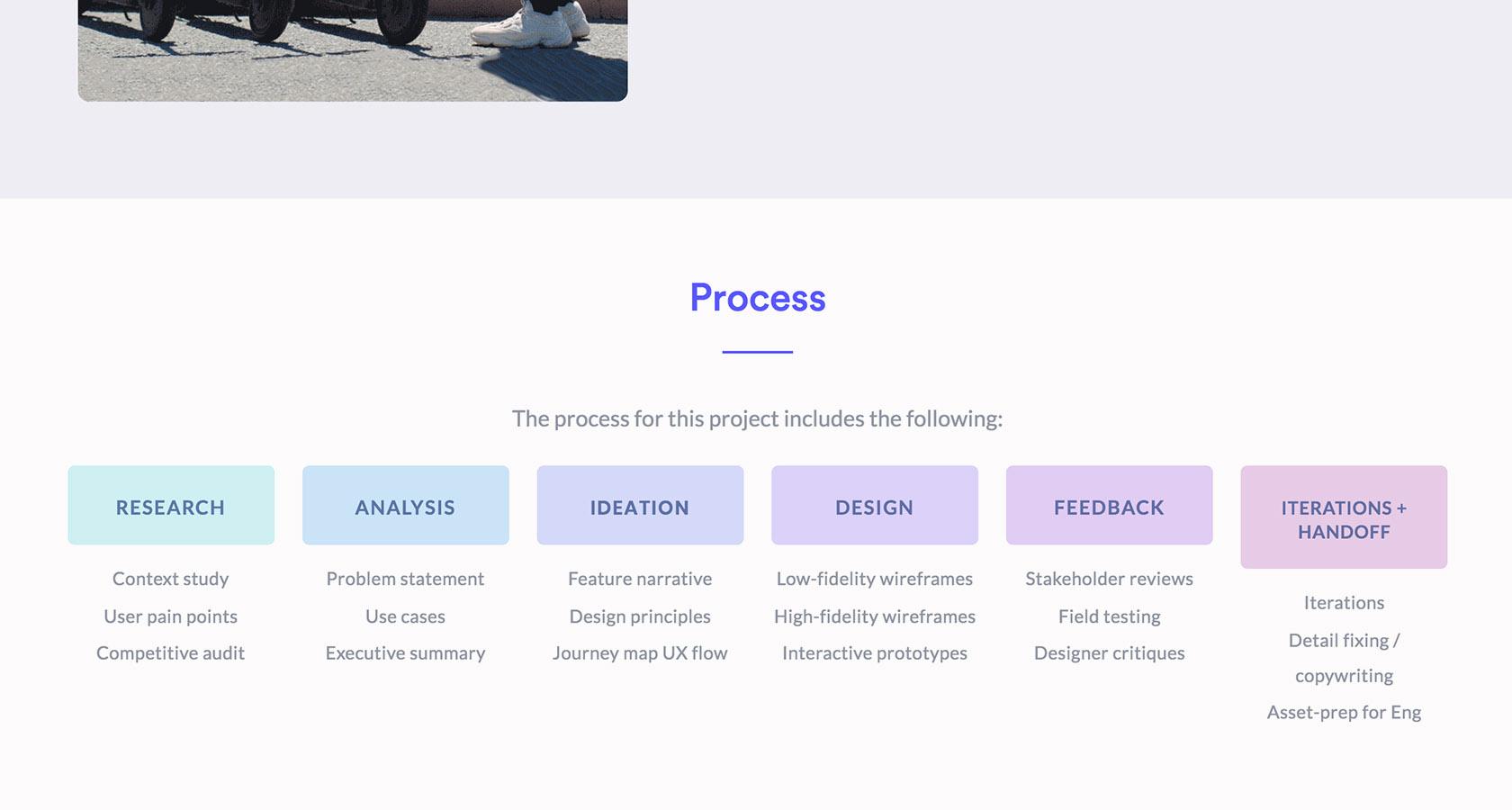

Walk through the steps of your design process.

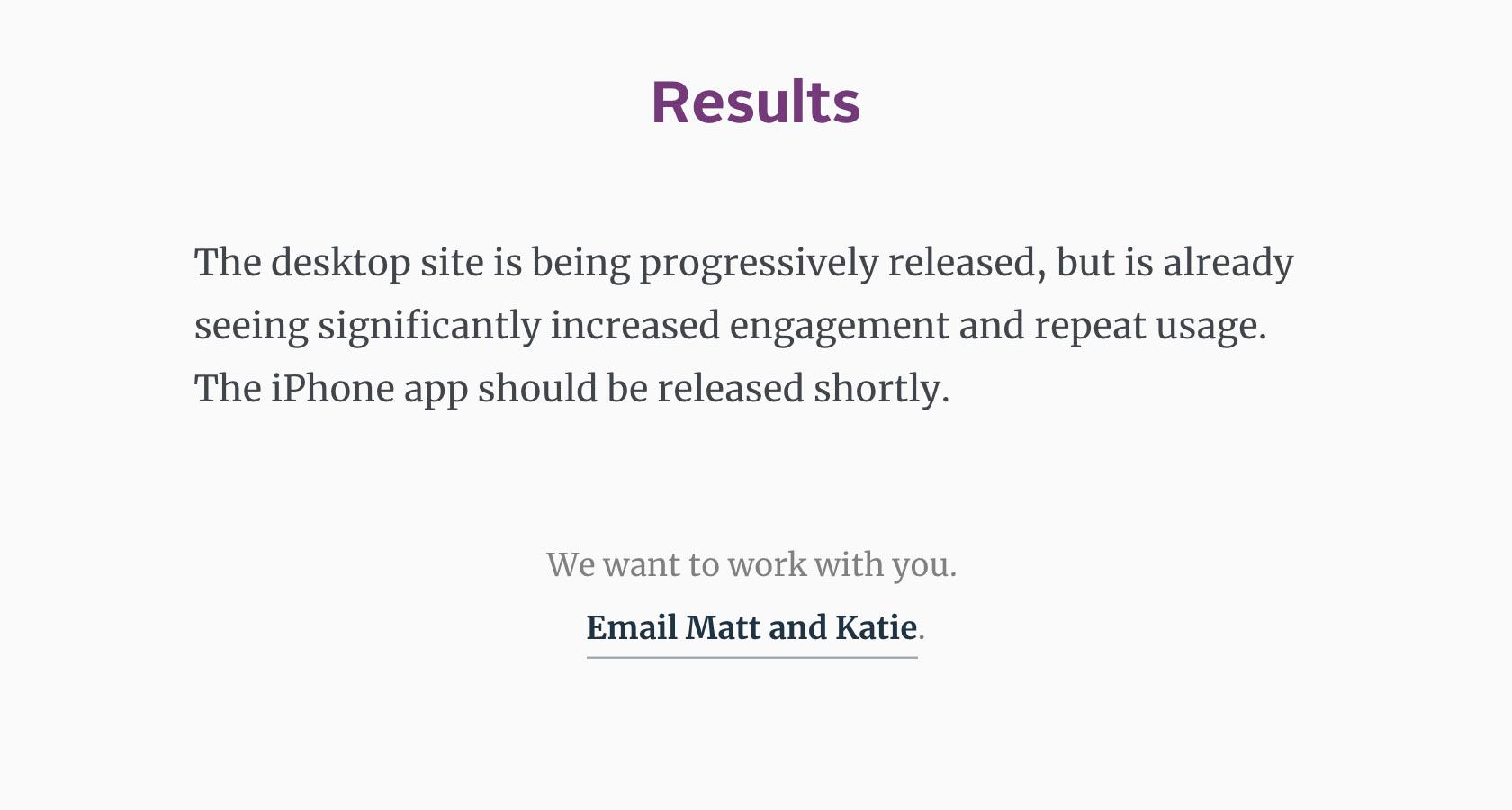

Describe the results.

Note any key learnings.

Wrap it all up with a short conclusion.

Happily, the core elements also outline a case study presentation format that’s simple, repeatable, and applicable to multiple disciplines. Let’s look closer:

- Who was the client?

- What industry are they in?

- What goods or services do they provide?

- Keep this section brief.

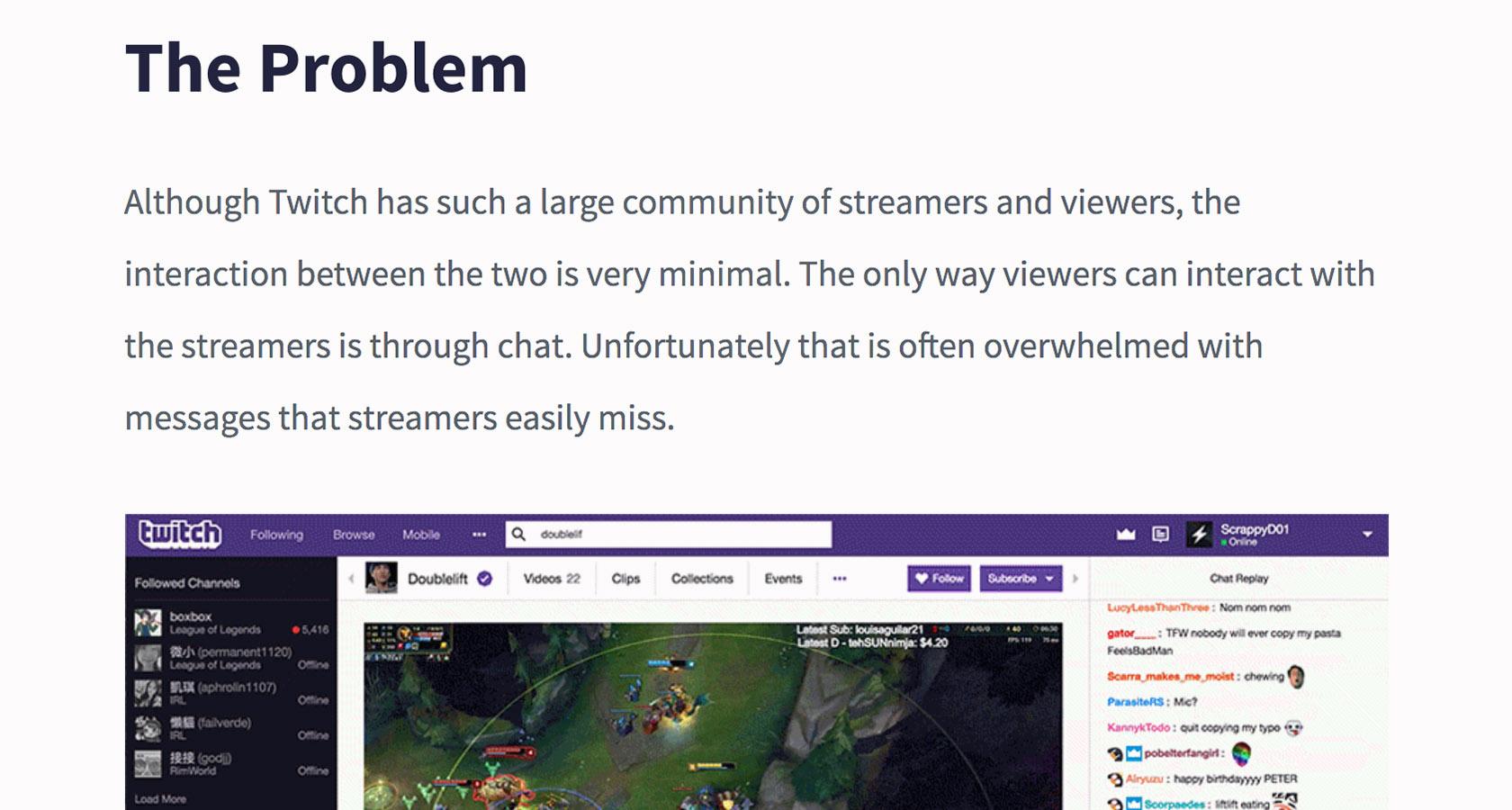

- What was the client’s problem?

- Why was it important that the problem be solved?

- Are there any additional background tidbits that might be helpful or interesting?

- What, specifically, were you hired to do?

- What were the constraints? Time. Budgetary. Technological. Etc.

- Before diving into your process, summarize the solution you designed.

- Make the summary short but powerful.

- Don’t give all the good parts away, and don’t be afraid to use language that makes your audience curious about the rest of the project.

- Go through the various steps of your discipline specific process.

- Again, summarize what you did, but don’t overload. Find a balance between informational and interesting.

- If you can, try to make each step introduce a question that only the following step can answer.

- Use this section to share a more robust description of the results of your design process.

- Be direct, avoid jargon, and don’t get too carried away with the amount of text you include.

- Don’t go overboard here, but if there are interesting things that you learned during the process, include them.

- If they won’t be helpful for the client, leave them out.

- Quickly summarize the project, and invite potential customers to contact you.

- It doesn’t hurt to provide a call to action and a contact link.

*Note: This isn’t the only case study format, just one that works. It’s helpful for people to encounter a predictable framework so they can focus on what they’re looking at as opposed to interpreting an inventive presentation structure.

The Value of Overlooked Details

Want to create a case study with a top notch user experience? Don’t underestimate the value of design details. Design projects are more than problem-meets-solution. They’re deeply human endeavors, and it makes a difference to clients when they see that a designer goes above and beyond in their work.

Share client feedback.

How did the client feel about your working relationship and the solution you provided? When you deliver top-notch work and nurture trust, get client feedback and include it in the case study as a testimonial.

If something you designed blew your client away, weave a testimonial into the case study (along with an image of what you made). This combo is proof positive to potential customers that you can deliver.

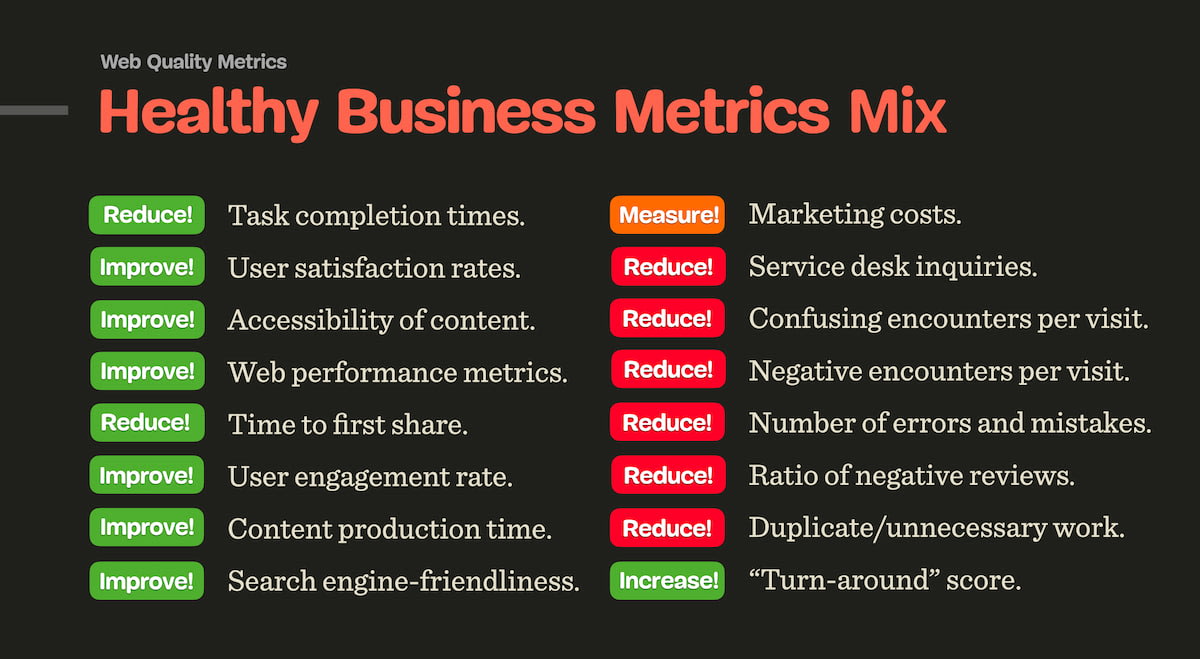

Explain positive metrics.

Not all design work has direct metrics that prove its success, but if your work does, and the results are impressive, include them. Just make sure that you don’t mislead (easy to do with statistics), and be careful that the metrics make sense to your audience.

Show unselected work.

Sometimes, amazing work from the design process doesn’t make it through to the finished product. These unused artifacts are helpful because they show an ability to explore a range of concepts.

Highlight unglamorous design features.

Not every aspect of design is glamorous. Like a pinky finger, small details may seem insignificant but they’re actually indispensable. Highlight these and recap why they matter.

Link to live projects.

It can be highly persuasive for a client to experience your work doing it’s thing out in the real world. Don’t hesitate to include links to live projects. Just make sure that your role in the project is clear, especially when you didn’t design everything you’re linking to.

Win Clients and Advance Careers with Case Study Portfolios

Designers need clients. We need their problems, their insights, their feedback, and their investments in the solutions we provide.

Since clients are so important, we ought to think about them often and strive to make entering into partnership with us as easy and painless as possible. Design portfolios are a first impression, an opportunity to put potential clients at ease and show that we understand their needs.

Case studies push our design portfolios past aesthetic allure to a level where our skills, communication abilities, and creativity instill trust and inspire confidence. Even better, they take clients out of a passive, browsing mindset to a place where “That looks cool,” becomes “That’s someone I’d like to work with.”

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- UX Portfolio Tips and Best Practices

- Ditch MVPs, Adopt Minimum Viable Prototypes (MVPrs)

- Breaking Down the Design Thinking Process

- The Best UX Designer Portfolios: Inspiring Case Studies and Examples

- Influence with Design: A Guide to Color and Emotions

Understanding the basics

How do i create a design portfolio.

Nowadays, it’s best to create a design portfolio online. Options vary: Some designers use a service like Behance or a WYSIWYG website builder like Squarespace, while others build custom sites with CSS. It’s also important that online design portfolios be responsive for multiple screen sizes.

How do I create an online portfolio for free?

Websites like Behance and Dribbble (among others) are free options for designers to publish online portfolios. Some designers have opted to forgo traditional web portfolios and instead document their work on social platforms like Instagram and Facebook. Free sites also take care of design portfolio layout.

How do you organize a design portfolio?

A designer ought to organize his portfolio according to his strengths. This means highlighting his best and most relevant work. Remember that design portfolios should be made with potential clients in mind. Avoid overly technical project descriptions, images without context, and excessively long case studies.

What is the purpose of a case study?

Many design portfolios consist of short project summaries and process images, but case studies are a way for designers to show their problem-solving skills to clients in greater detail. This is achieved by defining the client’s problem and the designer’s role, along with an overview of the designer’s process.

What are the advantages of a case study?

Case studies combine descriptive text and images and allow designers to demonstrate the details of their design processes to potential clients. They are also a great way for designers to highlight problem solving and small, but powerful, design features that may otherwise be overlooked.

- VisualDesign

- DesignProcess

Adnan Puzic

Sarajevo, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bosnia and Herzegovina

Member since September 28, 2015

About the author

World-class articles, delivered weekly.

By entering your email, you are agreeing to our privacy policy .

Toptal Designers

- Adobe Creative Suite Experts

- Agile Designers

- AI Designers

- Art Direction Experts

- Augmented Reality Designers

- Axure Experts

- Brand Designers

- Dashboard Designers

- Digital Product Designers

- E-commerce Website Designers

- Information Architecture Experts

- Interactive Designers

- Mockup Designers

- Presentation Designers

- Prototype Designers

- SaaS Designers

- Sketch Experts

- Squarespace Designers

- User Flow Designers

- User Research Designers

- Virtual Reality Designers

- Wireframing Experts

- View More Freelance Designers

Join the Toptal ® community.

The Ultimate Product Design Case Study Template

Learn how to write a product design case study that tells the story of your work and shows off your skills. Use our case study template to get started!

Written by Dribbble

Published on Oct 26, 2022

Last updated Mar 11, 2024

As a product designer, you might spend most of your time on user research, functionality, and user testing. But if you want to grow a successful product design career, you also need to present your work in a compelling way. This guide explains how to write a product design case study that makes other people want to hire you. It also includes several examples of amazing case studies to inspire you along with tips from senior designers and mentors from the Dribbble community.

What is a product design case study?

A product design case study is an in-depth analysis of a particular product or project, aimed at showcasing your design process, challenges, and outcomes. It usually includes information about who was involved in the project, the goals and objectives, research and ideation processes, design decisions and iterations, and the final product’s impact on the user and the market.

A product design case study is an in-depth analysis of a product or project, aimed at showcasing your design process, challenges, and outcomes.

Case studies provide a comprehensive understanding of the product design process, from the initial ideation to the final launch, highlighting the key factors that led to its success or failure. Product design case studies also showcase your design skills to prospective clients and employers, making it an important part of your product design portfolio .

What is the goal of a product design case study?

If you’re a designer growing your career, the main goal of your product design case studies is to share your design thinking process with hiring managers or prospective clients. Adding at least one case study to your product design portfolio can help you convince someone that you have the creativity and technical skills needed to solve their problems.

It’s one thing to list on your product design resume that you’re capable of designing high-fidelity prototypes, but it’s another to show exactly how you’ve helped other businesses overcome design-related challenges. A well-written case study shows design managers that you have experience with prototyping, animations, wireframes, user testing, and other tasks, making it easier to land a product design interview , or even better, a job offer.

What makes a good product design case study?

To make your case study as appealing as possible, make sure it checks all the right boxes.

A great product design case study:

- Tells a story

- Makes text and visuals come together to show how you added value to the design project

- Shows that you made important decisions

- Gives readers an understanding of your thought process

- Clearly defines the problem and the result

- Shows who you are as a designer

Product design case study template ✏️

Ready to start your next case study? Use our product design case study template created by Lead Product Designer @KPMG Natalia Veretenyk . Natalia is also a design mentor in Dribbble’s Certified Product Design Course helping new and seasoned product designers build their skills!

1. Project overview

Provide some background on the client featured in your case study. If you didn’t actually work with a client and are showcasing a course project, you can still provide context about the product or user you are designing for. Explain the design problem and describe what problem you were trying to solve.

Here’s an example: “ABC Company was selling 10,000 subscriptions per month, but its churn rate was over 35% due to a design flaw that wasn’t discovered during usability testing. The company needed to redesign the product to reduce its churn rate and increase user satisfaction.”

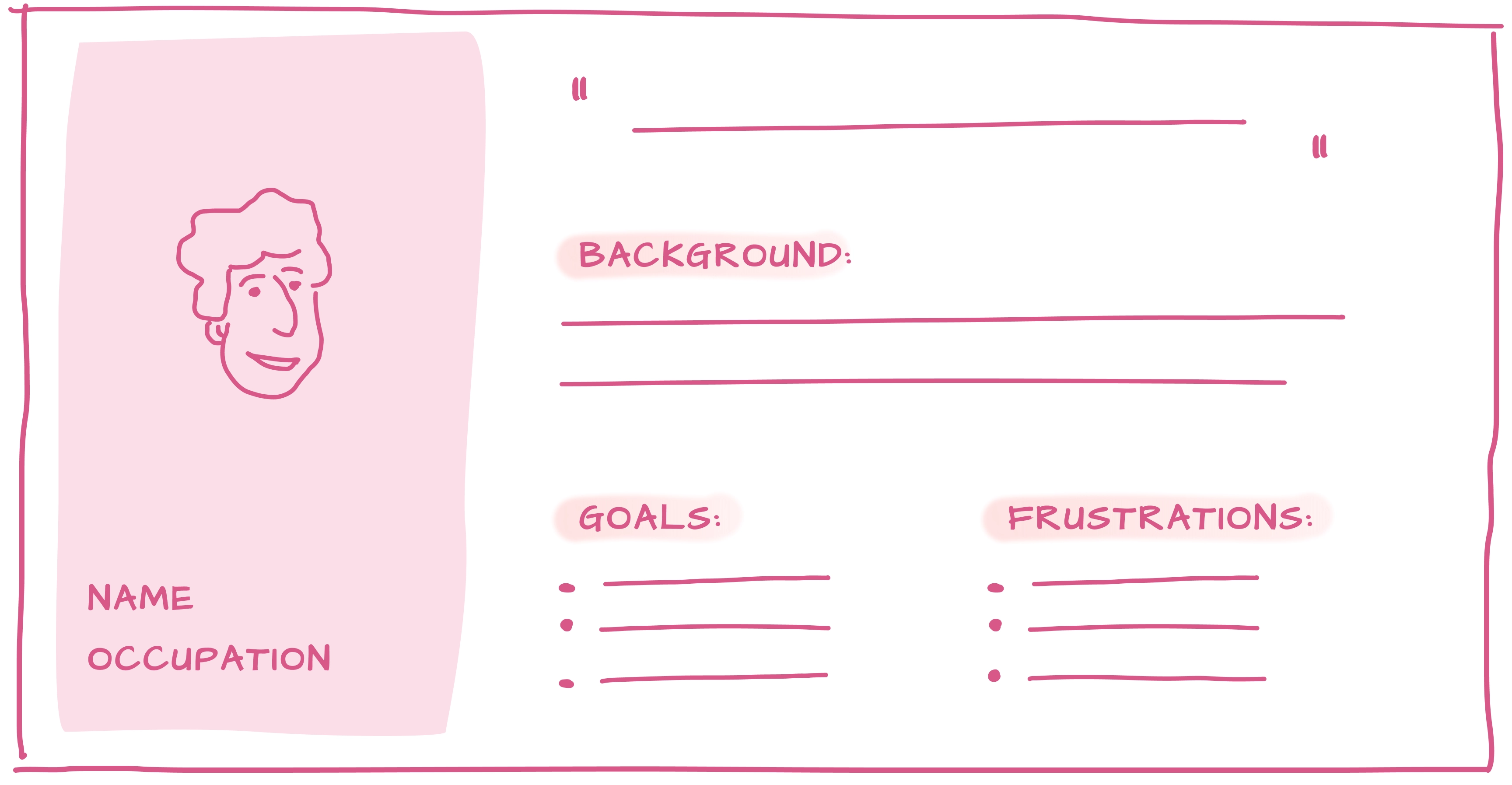

2. User research

Your case study should include some information about the target users for the project. This can help prospective clients or employers feel more comfortable about your ability to design products that appeal to their customers.

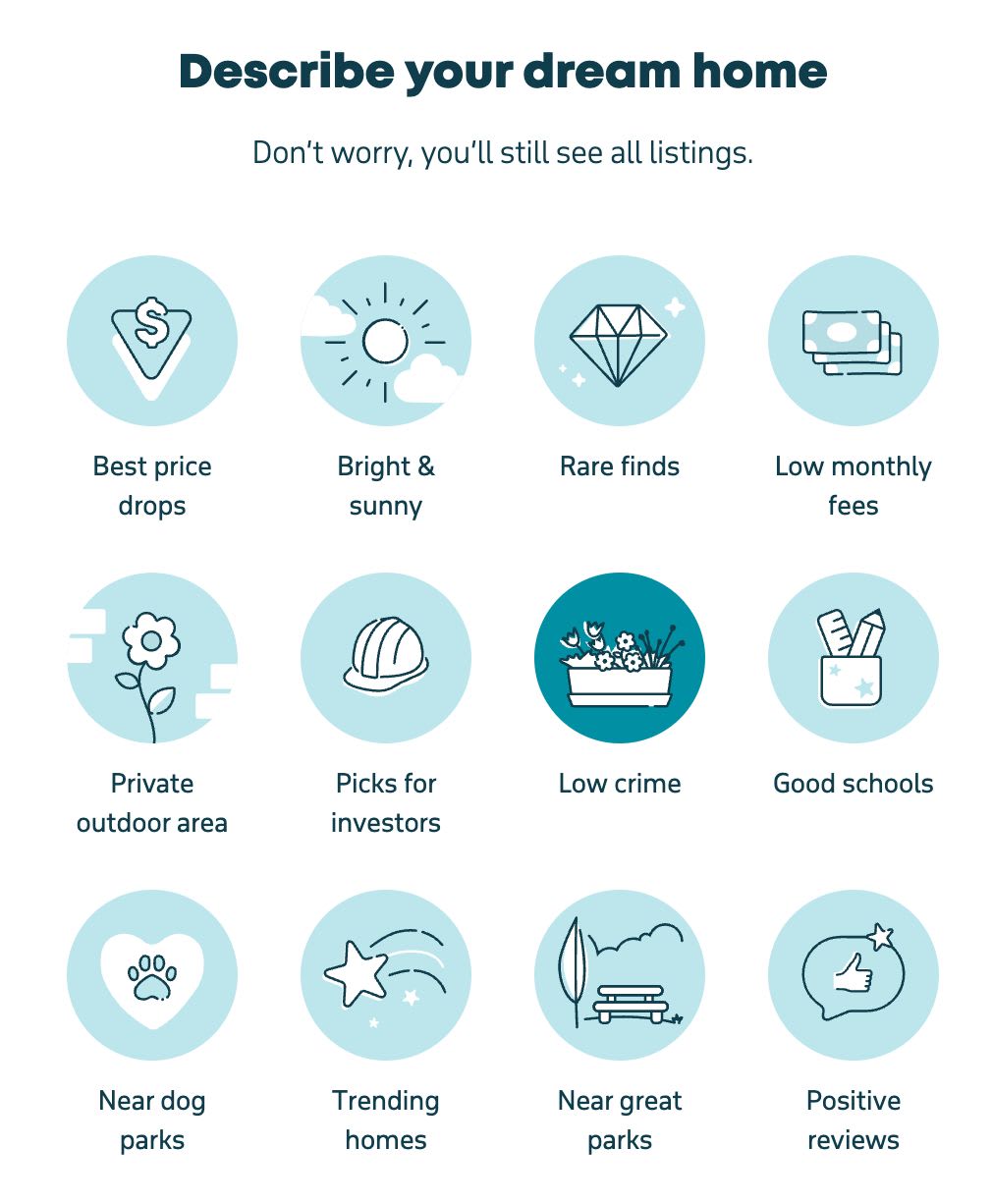

To include user research in your case study, start by explaining the methods used to collect data. This could be through surveys, interviews, user testing, or other methods. You should also explain the tools used to analyze and interpret the data, such as persona development or journey mapping .

You can also include information about the target audience itself. This can include demographic information like age, gender, location, education, and income. You should also mention any other relevant information about the user base, such as their interests, habits, or pain points.

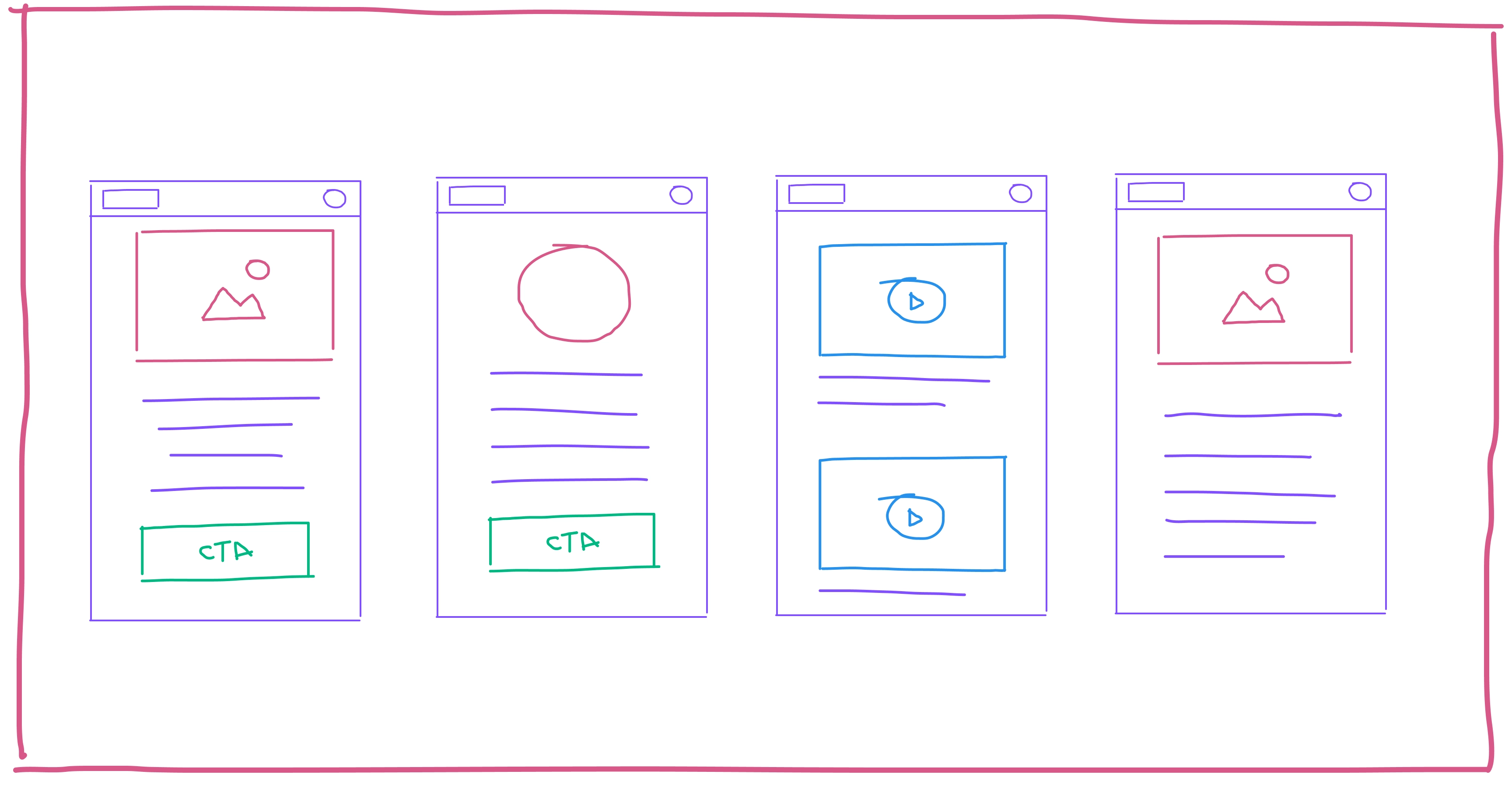

3. Ideating, wireframes, & prototyping

In this section, describe how you brainstormed ideas, created wireframes, and built prototypes to develop your product design. Be sure to explain the tools and techniques you used, such as sketching, whiteboarding, or digital software like Figma or Adobe XD. Also, highlight any challenges you faced during this process and how you overcame them.

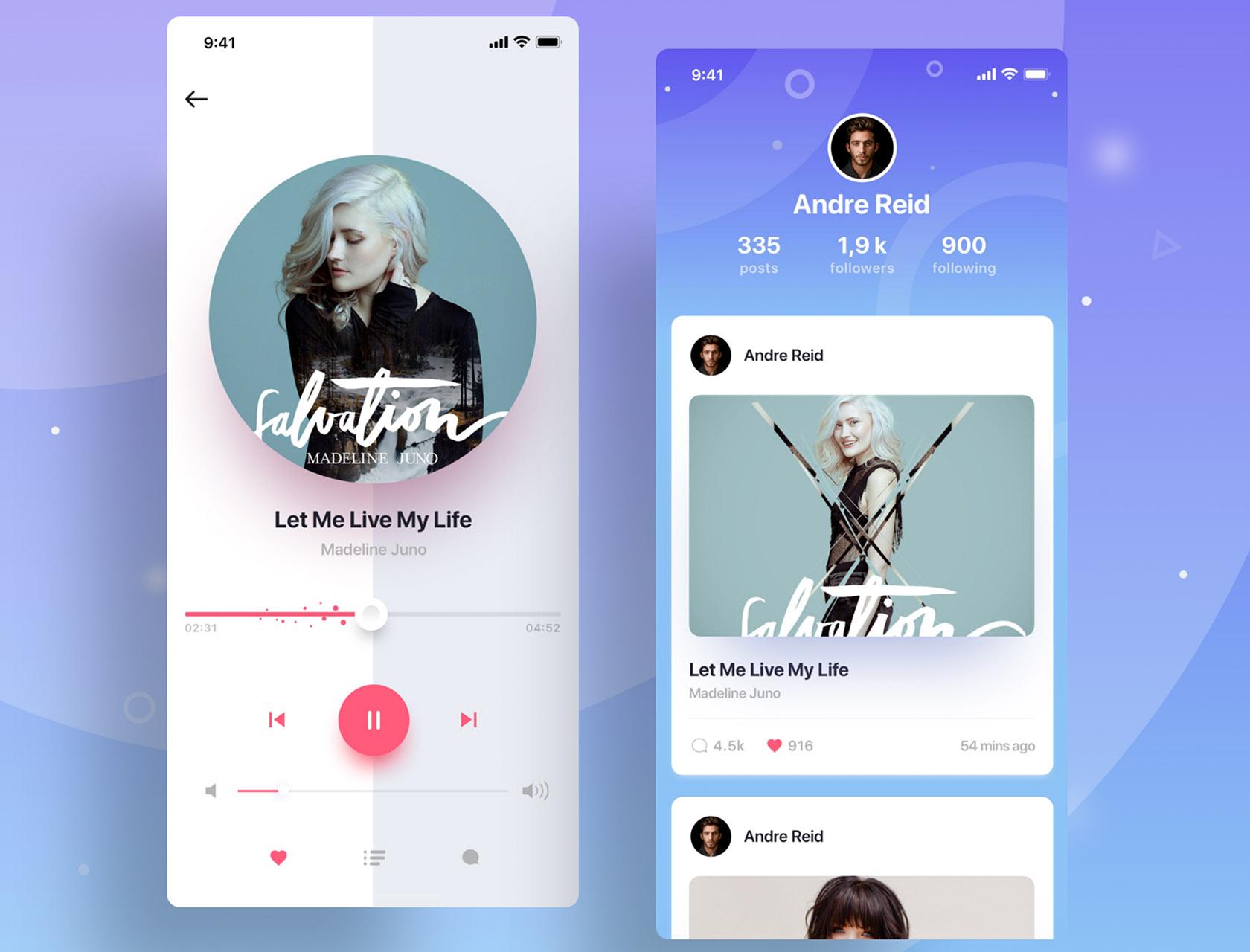

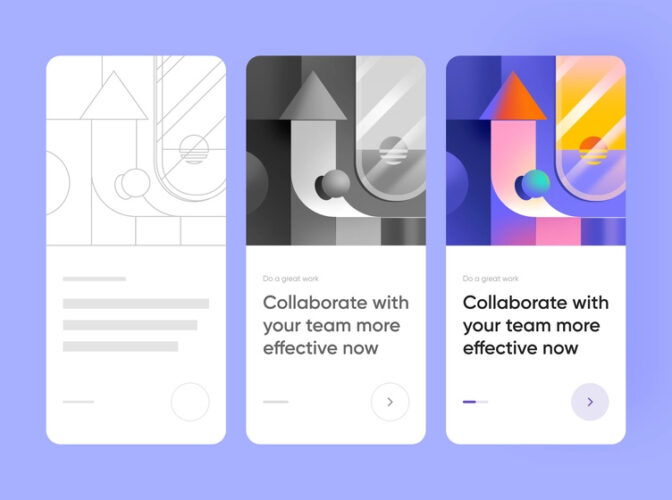

Include multiple images here to show the evolution of your design, showing the first and second rounds of iterations.

4. Visual design

Next, explain how you translated your wireframes and prototypes into a visually appealing design. Discuss your design choices, such as color schemes, typography, and imagery, and explain how they support the user experience. Include high-quality visuals of your final design and any design system or style guide you created. Lead Product Designer & Design Mentor Natalia Veretenyk recommends showcasing 4-10 main key mockup screens.

5. Usability testing

Write a short introduction to the usability testing you conducted and summarize your usability test findings. Explain the methods you used to conduct user testing, such as remote testing, in-person testing, or A/B testing. Describe the feedback you received from users and any changes you made to the design based on that feedback. If you didn’t have time to make any changes, write notes on what you might try next.

6. Outcomes and results

In this final section, you should summarize the impact of your design on the user and the business. Write up what you learned throughout the project. Insert 1 or 2 sentences summarizing the impact of your design on the user and the business. Include any relevant metrics, such as increased user engagement, higher conversion rates, or improved customer satisfaction.

As a bonus, you can also reflect on the design process and any lessons learned. This shows prospective clients and employers your ability to learn from your experiences and continuously improve your design skills.

Product design case study examples

If you need a little inspiration, check out the product design case study examples below. The designers did a great job explaining their design decisions and showing off their skills.

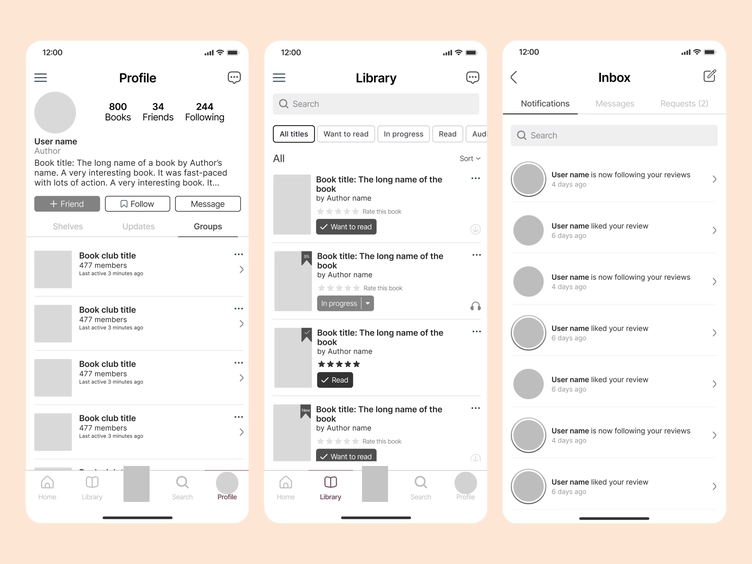

Instabook App by Tiffany Mackay

Tiffany Mackay’s Instabook case study starts out strong with a concise description of the client. She also includes a clear description of the design challenge: creating a social platform for authors, publishers, and readers. The case study includes wireframes and other visuals to show readers how Mackay developed new features and refined the tool’s overall user experience.

- View the full case study

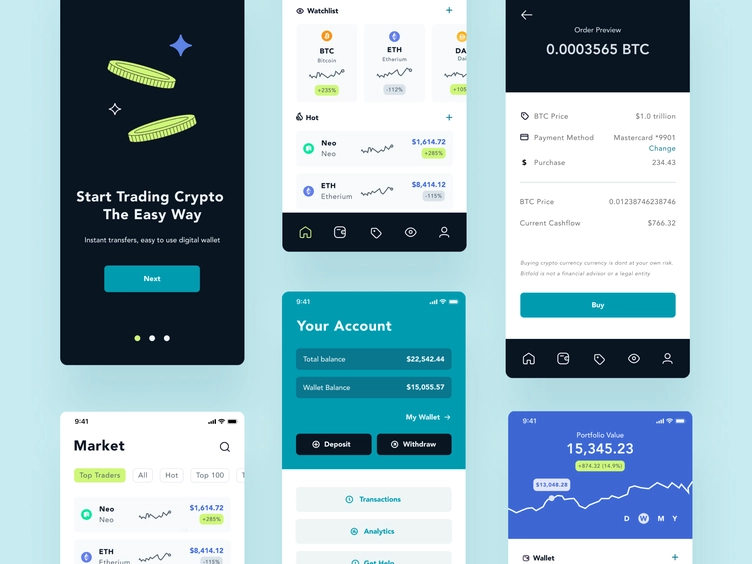

Crypto App by Brittney Singleton

The Crypto App case study is an excellent example of how to create a case study even if you don’t have much paid experience. Brittney Singleton created the Crypto App as a project for one of Dribbble’s courses, but she managed to identify a problem affecting the crypto marketplace and come up with a solution. Singleton’s case study contains plenty of visuals and explains the decisions she made at each stage of the project.

PoppinsMail by Antonio Vidakovik

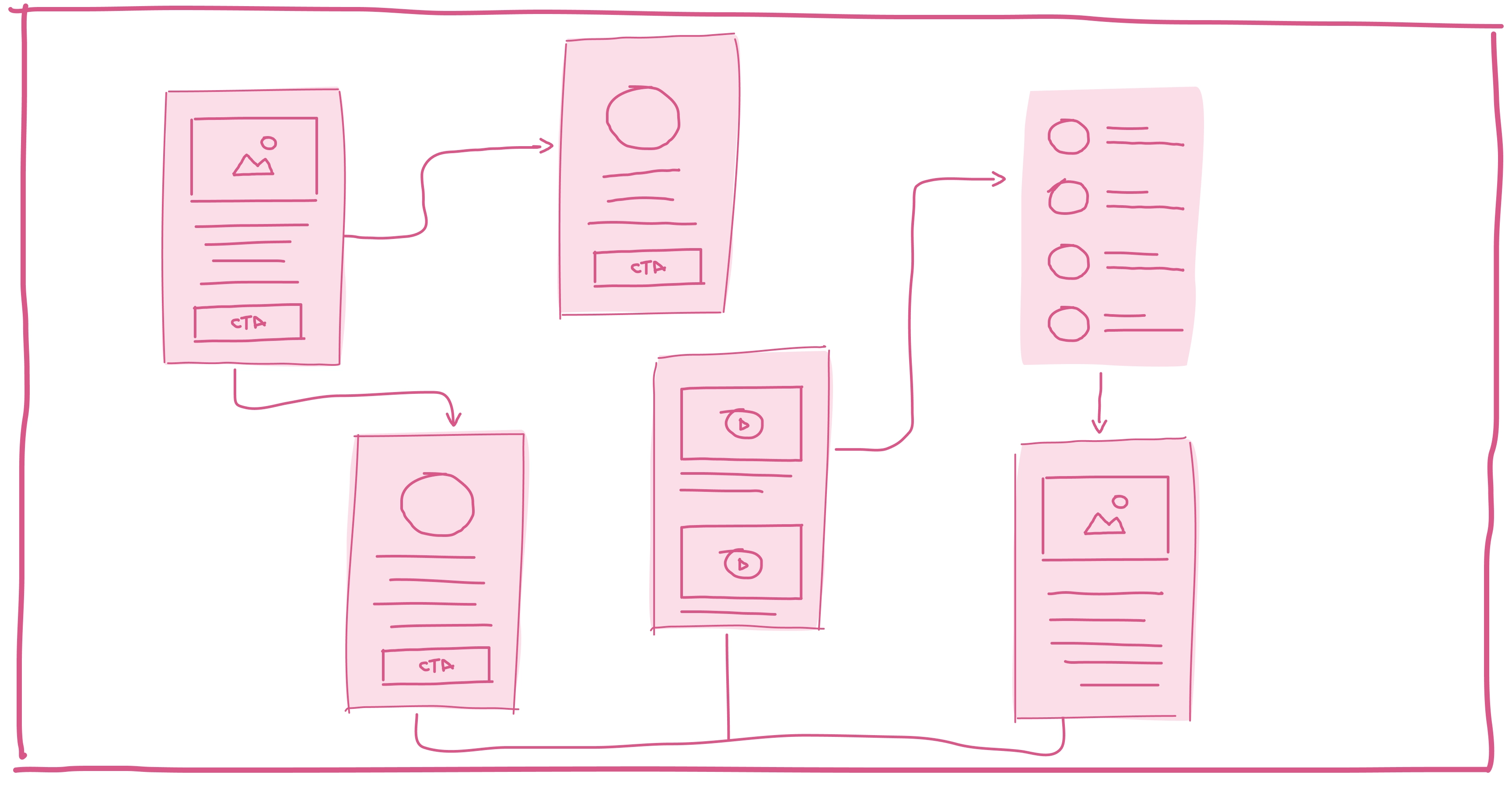

Antonio Vidakovik’s case study has some of the best visuals, making it a great example to follow as you work on your portfolio. His user flow charts have a simple design, but they feature bright colors and succinct descriptions of each step. Vidakovik also does a good job explaining his user interface design decisions.

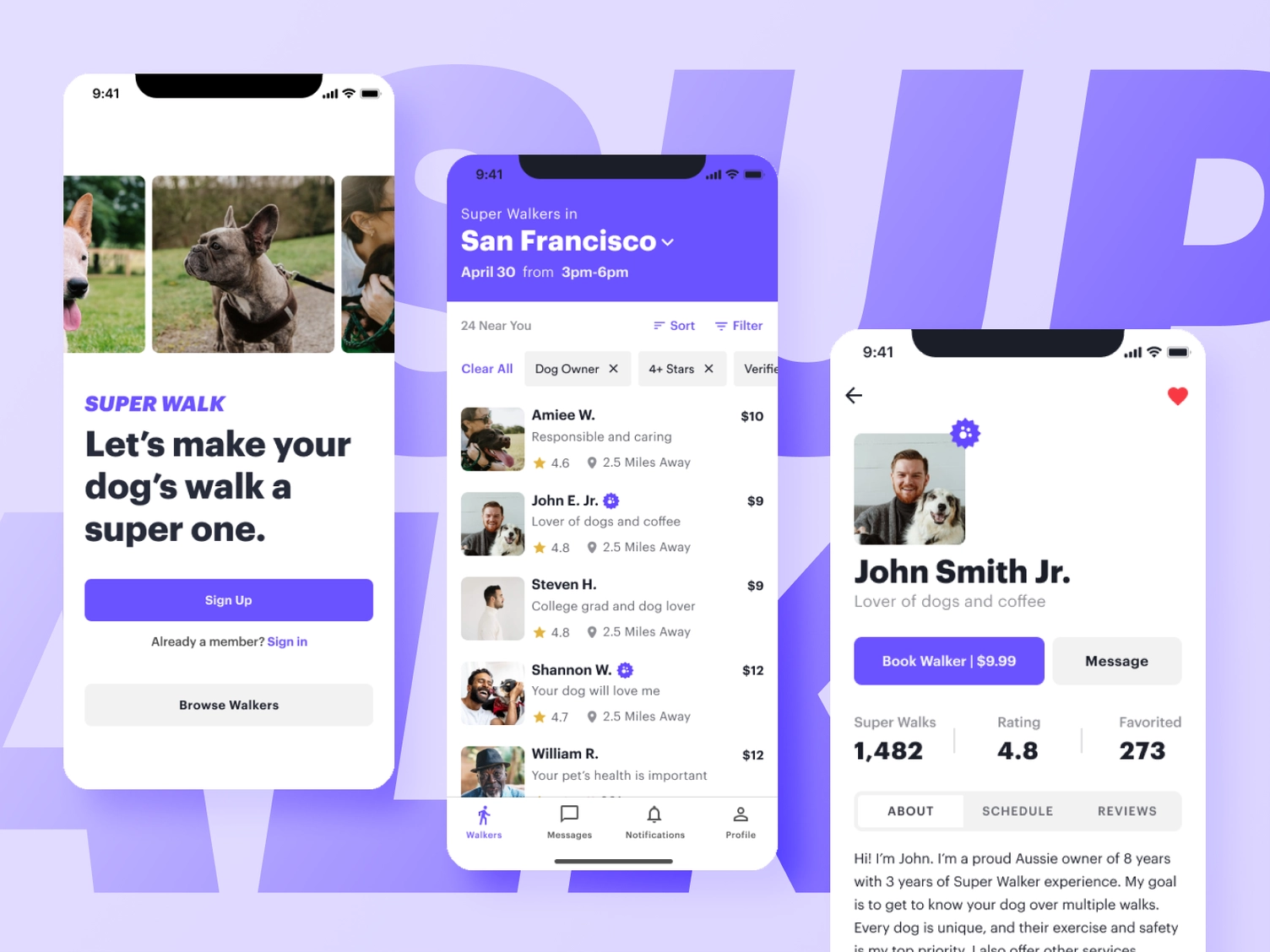

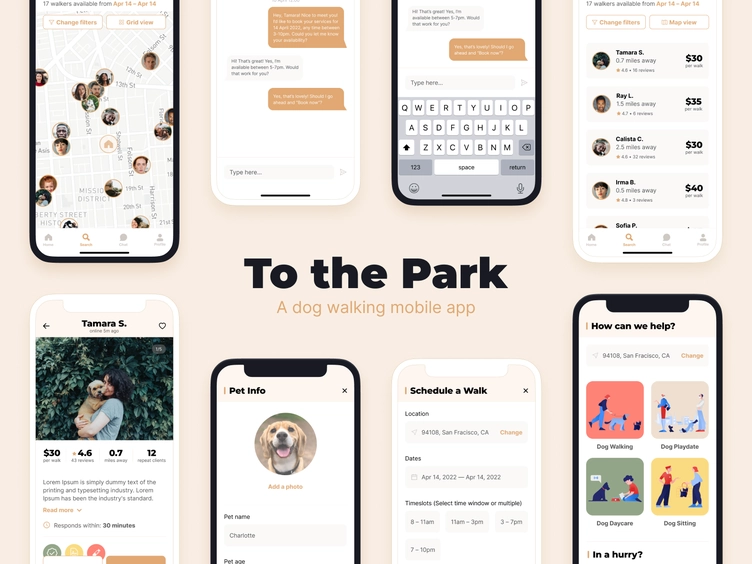

Super Walk by Micah Lanier

Micah Lanier offers a textbook example of an effective UX case study. It starts out with a quick overview of the client and a description of their problem. Micah also provides a detailed overview of the steps he took to identify user pain points, brainstorm solutions, and test several iterations before delivering a finished product. The Super Walk case study also includes plenty of visuals to show readers how the product evolved from the beginning to the end of the design process.

To the Park by Evangelyn

Evangelyn’s case study is another example of how you can show off your skills even if you don’t have years of professional experience. She created the To the Park app as a part of Dribbble’s Certified Product Design Course, so she had plenty of opportunities to create appealing visuals and conduct user testing. Her product design case study explains exactly how her design solves the initial challenge she identified.

How many case studies should I include in my product design portfolio?

If you have minimal experience, aim for two or three case studies. Like many junior product designers, you can use projects from a product design course you’ve completed if you don’t have a lot of professional experience. More experienced product designers should have up to five. Too many case studies can be overwhelming for recruiters, so don’t feel like you need to include dozens of projects.

Grow your product design portfolio

To get more product design jobs , try adding at least one product design case study to your portfolio website. Case studies include real-world examples of your work, making it easier for prospective clients and employers to assess your abilities. They’re different from resumes because they show people exactly what you can do instead of just listing your skills, making it more likely that you’ll get hired.

It's free to stay up to date

Ready for some inspiration in your inbox?

- For designers

- Hire talent

- Inspiration

- Advertising

- © 2024 Dribbble

- Freelancers

Get the course! 10h video + UX training

How To Write a Great Design Case Study

Case studies are often seen as documentation. But they can be more than that — digestible, thorough stories that showcase skills, values and process. Here are some examples to refer to when writing one.

How do we write a great design case study? I’ve put together some practical guides, examples and do’s and don’ts on how to stand out.

Key Takeaways #

- Think of a case study like a magazine feature.

- Keep a case study digestible, thorough and a story.

- Choose a customer that represents your scope of work.

- Promote the skills that you want to be hired for.

- Focus on insights rather than process.

- Show your intention and your values.

- Use the language that your future clients will understand.

- Teach readers something they don’t already know.

A fantastic example: Creating Slack's illustrations , neatly put together by Alice Lee.

I absolutely love diving into case studies that highlight wrong assumptions and failures, explaining how designers managed to turn the ship towards a better outcome. It’s a wonderful way to understand how a designer thinks, and that how they learn and adapt along the way.

Don’t be afraid to show your mistakes, and tell honest stories that your prospect clients can connect to. Probably the worst thing you could do is to create a polished, soulless, marketing version of your work that is too perfect to be true.

Authenticity and enthusiasm always shine through. Don’t hide them, and people will notice how incredible you are.

Design Case Study Examples and Guides #

A Complete Guide To Case Study Design , by Fabricio Teixeira, Caio Braga

Creating Slack's illustration voice , by Alice Lee

Reimagine the future of TV , by Abdus Salam

Designing Urban Walks , by Anton Repponen

Case Study Club , a curated hub by Jan Haaland

A Guide To Case Studies for Designers , by Jenny Kowalski

How to Write Project Case Studies For Your Portfolio , by Tobias van Schneider

Tips to Structuring Case Studies , by Lillian Xiao

How to Write Great UX Case Studies , by Yu Siang Teo

How To Write A Case Study For Your Design Portfolio

How To Write Trust-Building Case Studies (+ Templates) , by Elise Dopson

The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Good Case Study

How to Create Case Studies Without Any Past Projects

Related articles

Design Metrics and KPIs

A Guide For Designing For Older Adults

Practical Guide For UX and Design Managers

How To Fix a Bad User Interface

- Reviews / Why join our community?

- For companies

- Frequently asked questions

UX Case Studies

What are ux case studies.

A UX case study is a detailed analysis and narrative of a user experience (UX) design project . It illustrates a designer's process and solution to a specific UX challenge. A UX case study encompasses an explanation of the challenge, the designer’s research, design decisions and the impact of their work. UX designers include these case studies in their portfolios to demonstrate their experience, skills, approach and value to potential employers and clients.

“ Every great design begins with an even better story.” — Lorinda Mamo, Designer and creative director

Why UX Case Studies are Essential for a Successful Design Career

© Interaction Design Foundation, CC BY-SA 4.0

UX case studies are more than just documentation—they are powerful tools that advance a designer’s career and are integral to their success. They provide concrete evidence of a designer’s ability to tackle complex challenges from the initial user research to the final implementation of their solution. This transparency—a clear explanation and examination of the approach, thinking and methods—builds trust and credibility with potential clients and employers.

Beyond showcasing expertise, case studies encourage personal and professional growth . Through reflection and analysis, designers identify areas for improvement that hone their skills and deepen their understanding of user-centered design principles. What’s more, when designers compile and refine their case studies, they strengthen communication skills which allows them to articulate, rationalize and present data effectively.

For potential employers and clients, case studies give insight into a designer’s thought process and problem-solving approach . They reveal how designers gather and analyze user data, iterate on designs, and ultimately deliver solutions. This level of insight goes beyond resumes and qualifications as they provide tangible evidence of a designer's ability to research, reason and create user-centered products that meet business objectives. Ultimately, UX case studies empower designers to tell their unique story, stand out in a competitive market and forge a successful career in the evolving field of UX design.

How to Approach UX Case Studies

Recruiters want candidates who can communicate through designs and explain themselves clearly and appealingly. Recruiters will typically decide within five minutes of skimming UX portfolios whether a candidate is a good fit. Quantity over quality is the best approach to selecting case studies for a portfolio. The case studies should represent the designer accurately and positively. So, they should illustrate a designer’s entire process and contain clear, engaging, error-free copywriting and compelling visual aids. Designers can convince recruiters they’re the right candidate when they portray their skills, thought processes, choices and actions in context through engaging, image-supported stories.

- Transcript loading…

Content strategy, too, is a fundamental aspect of UX design case studies and portfolios. In the next video, Morgane Peng talks about content strategy in the context of case studies and design portfolios.

How to Build Successful UX Case Studies

Case studies should have an active story with a beginning, middle and end—never a flat report. So, a designer would write, e.g., “We found…”, not “It was found…”. Designers must always get their employer’s/client’s permission when they select case studies for their portfolios. Important information should be anonymized to protect your employer’s/client’s confidential data (by changing figures to percentages, removing unnecessary details, etc.). What is anonymized or omitted depends on whether a non-disclosure agreement (NDA) is involved.

Step-by-Step Guide: How to Create a UX Case Study

1. Choose the right project: Whether this is for a web-based portfolio or one created for a specific job, choose a project that showcases the best, most relevant work and skills. Make sure permission is granted to share the project, especially if it involves client work.

2. Define the problem: Clearly articulate the problem addressed in the project. Explain its significance and why it was worth solving. Provide context and background information about the project, including the target audience and stakeholders.

3. Establish your role and contribution: Detail specific responsibilities and contributions to the project. Highlight collaboration with team members to showcase teamwork and communication too.

4. Describe the process: Include research methods used (e.g., user interviews, surveys) and the insights gained. Use quotes , anecdotes and even photographs and artifacts from user research to bring the story to life. Introduce user personas developed from the research to add depth to the narrative. Insert user journey maps to visualize the user experience and identify pain points.

5. Illustrate the design and development journey: Show the initial wireframes and prototypes . Explain the iteration process and how feedback was incorporated. Explain the reasons behind design choices , supported by visuals like sketches, wireframes, and prototypes. Mention the tools and techniques used during the design process.

6. Highlight the testing and iteration phase: Detail the usability tests conducted and key findings. Use real user feedback to add authenticity to the story. Describe how feedback was used to make iterations to demonstrate a commitment to continuous improvement.

7. Showcase the final solution: Present high-fidelity mockups of the final design. Highlight key features and functionalities. Discuss final product’s visual and functional aspects with the use of visuals to enhance the narrative.

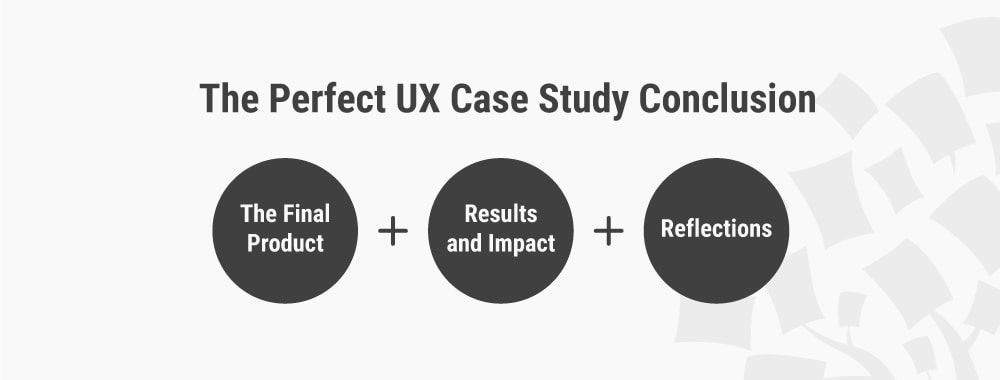

8. Conclude with results and impact: Describe the results, including metrics and data that demonstrate the impact (e.g., increased user engagement, improved usability). Reflect on the lessons learned during the project—mention any challenges faced and how they were overcome.

9. Present the story: Make sure the case study tells a compelling story with a clear beginning, middle, and end. Check to see where images, charts, and other visuals can be added to further support the story. Ensure visuals are well-integrated and enhance the narrative. Keep the narrative concise and focused—always avoid unnecessary details and jargon.

10. Final review and polishing: Reread, edit and proofread—the case study should be clear, well-written, free of errors, and professional. It’s always advisable to get feedback from peers or mentors to refine the case study.

In this video, Michal Malewicz, Creative Director and CEO of Hype4, has some tips for writing great case studies.

Storytelling for Case Studies: How to Hook Hiring Managers and Clients

Consider Greek philosopher Aristotle’s storytelling elements and work with these in mind when getting started on a case study:

Plot : The career- or job-related aspect the designer wants to highlight. This should be consistent across case studies for the specific role for which they’re applying. So, if they want to land a job as a UX researcher, they must focus on the relevant skills—user research methods—in their case studies.

Character : A designer’s expertise in applying industry standards and working in teams.

Theme : Goals, motivations and obstacles of their project.

Diction : A friendly, professional tone in jargon-free language.

Melody : Your passion—for instance, where a designer proves that design is a lifelong interest as opposed to just a job.

Décor : A balance of engaging text and images.

Spectacle : The plot twist/wow factor—e.g., a surprise discovery. Naturally this can only be included if there was a surprise discovery in the case study.

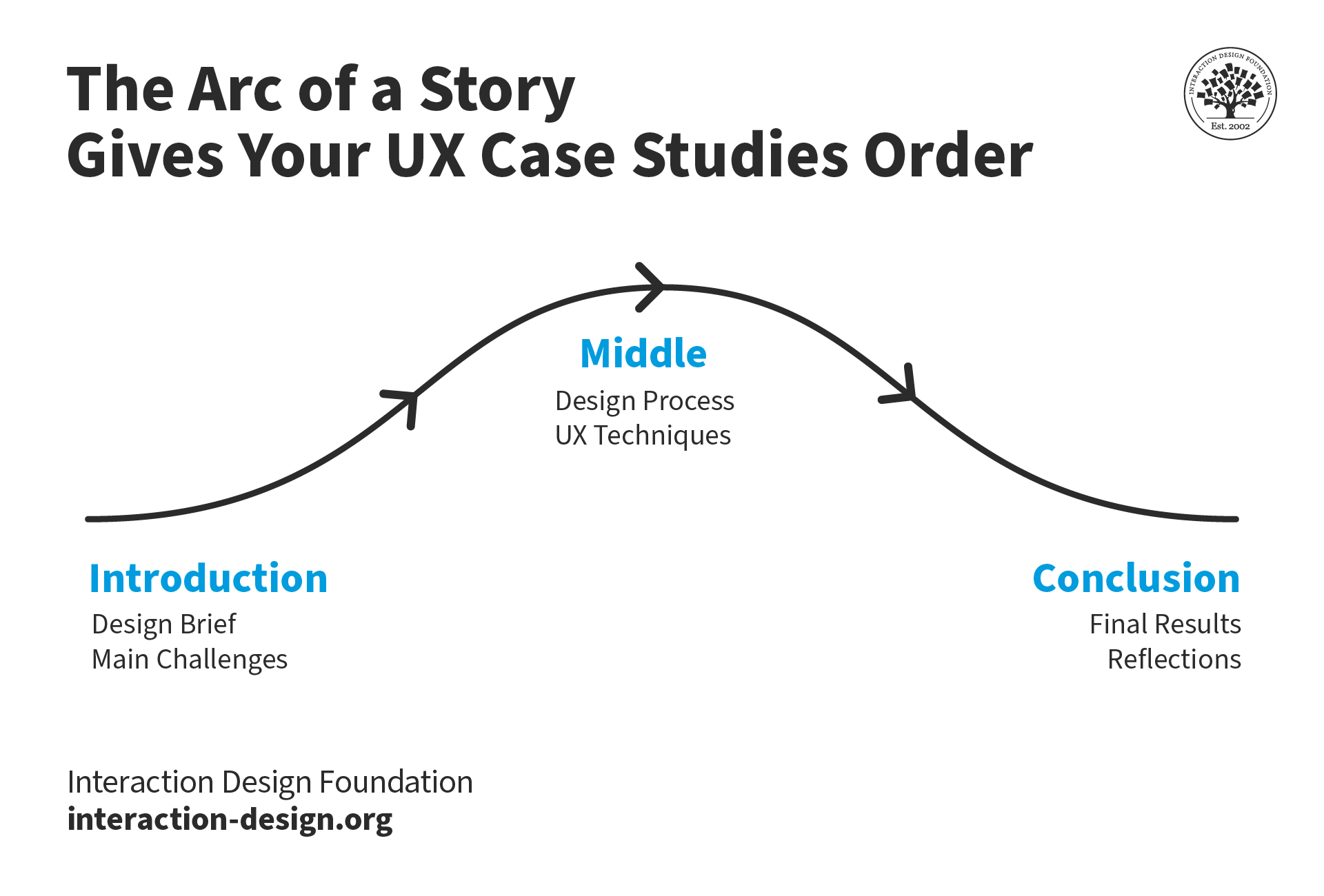

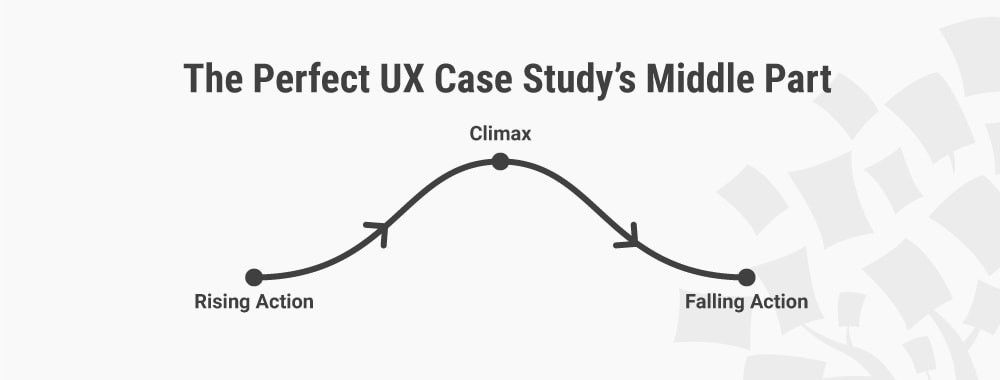

All good stories have a beginning, a middle and an end.

© Interaction Design Foundation. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

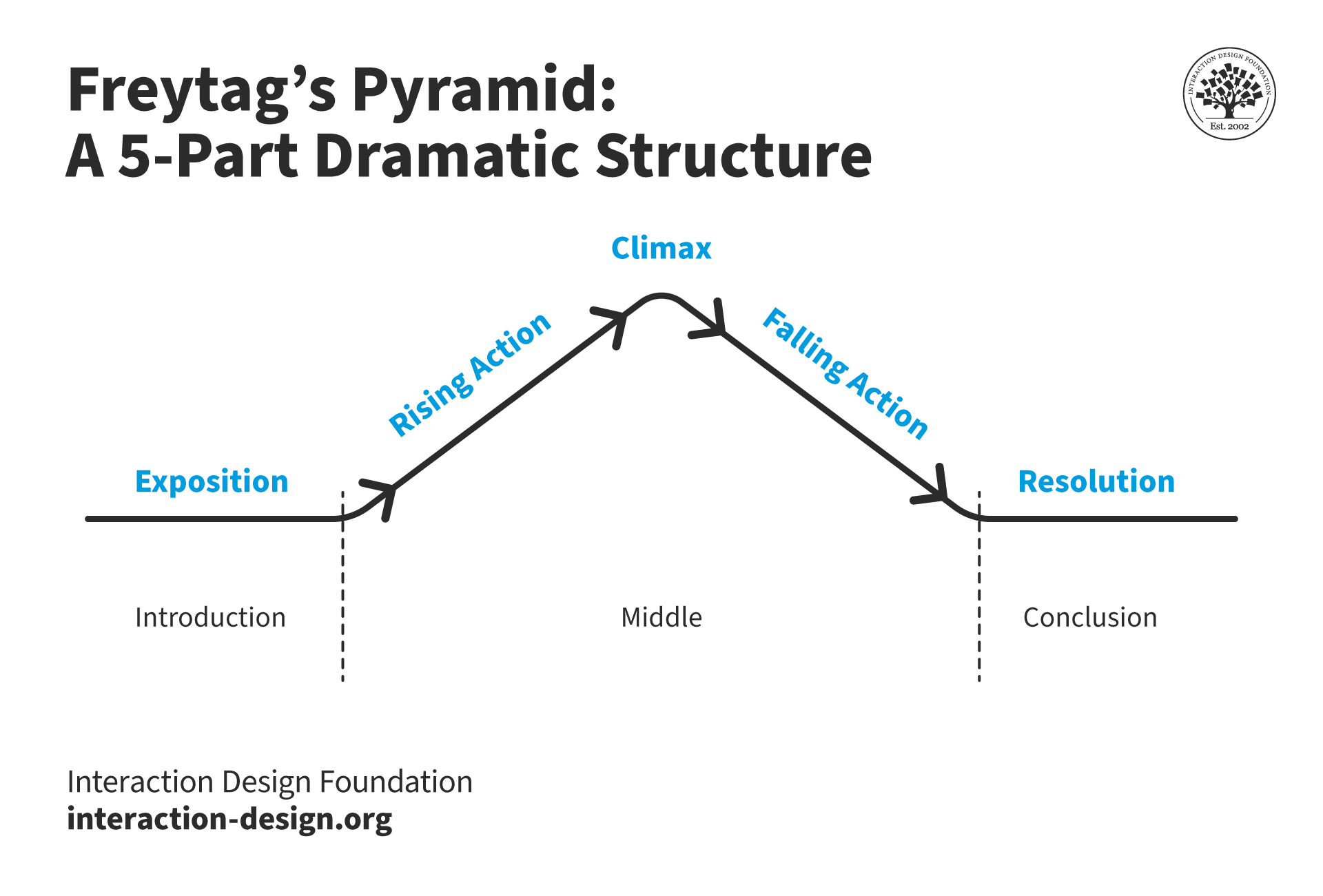

Designers can also take inspiration from German novelist-playwright Gustav Freytag’s 5-part pyramid to structure their case studies and add a narrative flow:

Typical dramatic structure consists of an exposition and resolution with rising action, climax and falling action in between.

Exposition — the introduction or hook (4–5 sentences) . This should describe the:

Problem statement : Include the motivations and thoughts/feelings about the problem.

The solution : Outline the approach. Hint at the outcome by describing the deliverables/final output.

The role: What role was played, what contribution was made.

Stages 2-4 form the middle (more than 5 sentences). Summarize the process and highlight the decisions:

Rising action : Outline some obstacles/constraints (e.g., budget) to build conflict and explain the design process (e.g., design thinking ). Describe how certain methods were used, e.g., qualitative research to progress to one or two key moments of climax.

Climax : Highlight this, the story’s apex, with an intriguing factor (e.g., unexpected challenges). Choose only the most important information and insights to tighten the narrative and build intrigue.

Falling action: Show how the combination of user insights, ideas and decisions guided the project’s final iterations. Explain how, e.g., usability testing helped shape the final product.

Stage 5 is the conclusion:

Resolution (4–5 sentences) : Showcase the end results as how the work achieved its business-oriented goal and what was learned. Refer to the motivations and problems described earlier to bring the story to an impressive close.

Overall, the case study should:

Tell a design story that progresses meaningfully and smoothly.

Tighten/rearrange the account into a linear, straightforward narrative .

Reinforce each “what” that’s introduced with a “how” and “why”.

Support text with the most appropriate visuals (e.g., screenshots of the final product, wireframing , user personas , flowcharts , customer journey maps , Post-it notes from brainstorming ). Use software (e.g., Canva, Illustrator) to customize visually appealing graphics that help tell a story.

Balance “I” with “we” to acknowledge team members’ contributions and shared victories/setbacks.

Make the case study scannable , e.g., Use headings, subheadings etc.

Remove anything that doesn’t help explain the thought process or advance the story.

Learn More about UX Case Studies

Take our course Build a Standout UX/UI Portfolio: Land Your Dream Job .

Read our article Turn Your Non-Design Experience into Design Portfolio Gold .

Read our article 7 Design Portfolio Mistakes That Are Costing You Jobs! And How to Fix Them .

UX designer and entrepreneur Sarah Doody offers advice in How to write a UX case study .

Learn what can go wrong in UX case studies in the article 7 Case Study Mistakes You Are Making in Your UX Portfolio .

Questions related to UX Case Studies

A UX case study showcases a designer's process in solving a specific design problem. It includes a problem statement, the designer's role, and the solution approach. The case study details the challenges and methods used to overcome them. It highlights critical decisions and their impact on the project.

The narrative often contains visuals like wireframes or user flowcharts. These elements demonstrate the designer's skills and thought process. The goal is to show potential employers or clients the value the designer can bring to a team or project. This storytelling approach helps the designer stand out in the industry.

To further illustrate this, consider watching this insightful video on the role of UX design in AI projects. It emphasizes the importance of credibility and user trust in technology.

Consider these three detailed UX/UI case studies:

Travel UX & UI Case Study : This case study examines a travel-related project. It emphasizes user experience and interface design. It also provides insights into the practical application of UX/UI design in the travel industry.

HAVEN — UX/UI Case Study : This explores the design of a fictional safety and emergency assistance app, HAVEN. The study highlights user empowerment, interaction, and interface design. It also talks about the importance of accessibility and inclusivity.

UX Case Study — Whiskers : This case study discusses a fictional pet care mobile app, Whiskers. It focuses on the unique needs of pet care users. It shows the user journey, visual design, and integration of community and social features.

Writing a UX case study involves several key steps:

Identify a project you have worked on. Describe the problem you addressed.

Detail your role in the project and the specific actions you took.

Explain your design process, including research , ideation , and user testing.

Highlight key challenges and how you overcame them.