Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

103 Prison Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Prison Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Prisons are an integral part of the criminal justice system, serving as a means of punishment, rehabilitation, and deterrence for individuals who have committed crimes. Writing an essay on prison-related topics can be a thought-provoking and challenging task. To help you get started, here are 103 prison essay topic ideas and examples:

- The effectiveness of prison as a form of punishment

- The impact of incarceration on mental health

- The role of prisons in reducing recidivism rates

- The overcrowding crisis in prisons

- The ethics of for-profit prisons

- The impact of prison privatization on inmate rights

- The experiences of LGBTQ+ individuals in prison

- The racial disparities in the criminal justice system

- The challenges faced by elderly inmates

- The impact of the war on drugs on mass incarceration

- The rehabilitation programs offered in prisons

- The use of solitary confinement as a punishment

- The mental health treatment available to inmates

- The impact of prison labor on inmate rights

- The role of education in prisoner rehabilitation

- The impact of family visitation policies on inmates

- The experiences of women in prison

- The impact of the death penalty on prison populations

- The debate over juvenile sentencing and incarceration

- The impact of COVID-19 on prison populations

- The role of faith-based programs in prisoner rehabilitation

- The impact of parole policies on recidivism rates

- The experiences of individuals with disabilities in prison

- The impact of immigration detention on inmates

- The role of mental health courts in diverting individuals from prison

- The impact of mandatory minimum sentencing laws on prison populations

- The experiences of transgender individuals in prison

- The role of restorative justice programs in prisoner rehabilitation

- The impact of drug addiction on incarceration rates

- The use of technology in prison management

- The experiences of individuals with mental illnesses in prison

- The impact of mass incarceration on communities of color

- The role of reentry programs in reducing recidivism rates

- The impact of the school-to-prison pipeline on youth incarceration rates

- The experiences of individuals serving life sentences

- The impact of pretrial detention on inmates

- The role of mental health diversion programs in reducing incarceration rates

- The impact of retribution on prison policies

- The experiences of individuals serving long-term sentences

- The impact of the criminalization of poverty on incarceration rates

- The role of prison industries in inmate rehabilitation

- The impact of solitary confinement on mental health

- The experiences of individuals serving death row sentences

- The impact of mandatory drug sentencing laws on prison populations

- The role of restorative justice in reducing recidivism rates

- The impact of the cash bail system on pretrial detention rates

- The experiences of individuals who have been wrongfully convicted

- The impact of the school-to-prison pipeline on youth of color

- The role of community-based alternatives to incarceration

- The impact of the war on drugs on incarceration rates

- The experiences of individuals serving life without parole sentences

- The role of for-profit prisons in the criminal justice system

- The impact of solitary confinement on inmate mental health

- The role of rehabilitation programs in reducing recidivism rates

- The impact of overcrowding in prisons

- The ethics of capital punishment

- The impact of racial disparities in the criminal justice system

- The impact of the privatization of prisons

- The role of mental health treatment in inmate rehabilitation

- The experiences of juvenile inmates

- The impact of restorative justice programs on recidivism rates

- The role of parole boards in determining release dates

- The impact of mandatory sentencing laws on prison populations

- The impact of immigration policies on inmate populations

- The impact of reentry programs on reducing recidivism rates

- The role of technology in prison management

These essay topic ideas cover a wide range of issues related to prisons and incarceration. Whether you are interested in the ethics of for-profit prisons, the impact of mental health treatment on inmate rehabilitation, or the experiences of transgender individuals in prison, there is a topic here for you. Use these ideas as a starting point for your research and writing, and delve deeper into the complex and challenging world of prisons and the criminal justice system.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

- IELTS Scores

- Life Skills Test

- Find a Test Centre

- Alternatives to IELTS

- All Lessons

- General Training

- IELTS Tests

- Academic Word List

- Topic Vocabulary

- Collocation

- Phrasal Verbs

- Writing eBooks

- Reading eBook

- All eBooks & Courses

Prison Essays

by Hayder Ahmed (Leeds, UK)

I also agree

| Jan 04, 2016 | It's a nice essay, but it's too long, u can't manage to write such a long essay in 40 minutes only. Another problem is that there is no precise conclusion. Though there is, its very vague. Another problem is lack of connective words. |

| Jan 26, 2017 | Gooooooooooooood essay |

| Jan 26, 2017 | Great essay I agree with the essay. |

| Feb 11, 2017 | I like this essay, It's giving me a lot of ideas that I needed. Love it so much. Thank you for posting this wonderful essay. |

| Sep 08, 2020 | The person who commented that this needs to be done in under 40 min is braindead. It's for aice, nice essay bro. |

| Oct 14, 2020 | It's not islamic society is it, it's certain countries such as Saudi Arabia that do it, not islamic society's. Apart from that very good. |

Click here to add your own comments

Alternatives to Prison

by Lenah (Yemen)

Some people think that the best way to reduce crime is to give longer prison sentences. Others, however, believe there are better alternative ways of reducing crime. Discuss both views and give your opinion. Crime by all of its types is a dangerous problem which start expanding in some countries. A lot of governments trying to reduce its. Some people think that the best way to stop this problem is put criminals in the prison for longer period. Others, believe that there are more different solutions can effect better than first opinion. In this essay I am going to discuss these two opinions. There are benefits for give longer prison sentences. Firstly, this judgment will be a strong deterrent for the criminal. Furthermore, it isolates the offender from society. Therefore will produce a safety society and free of crime. Moreover, when the prisoner spends long time in the prison that will help an opportunely service to rehabilitate him. However, Some people believe that spending longer time in prison will mix the prisoner with other criminals, so his character will not improve and this thing increases the problem worse. One thing will solve that is Judgment on the prisoner's civil and social work service with an electronic bracelet around his foot to follow him. This solution has a lot of advantages. First of all, this thing will improve the behavior of offender. Another advantage is this thing will help prisoner to be more respectable with everybody. Therefore, prisoner can mix with society under government following. In my opinion, Making the criminal acts of the civil and social service with an electronic device will create a safety society. This solution is very useful than other. Finally, government should decided which ways are have more positive effects than other, for a society free of crimes and dangerous. *** Help this IELTS candidate to improve their score by commenting below on this essay on reducing crime.

|

| |

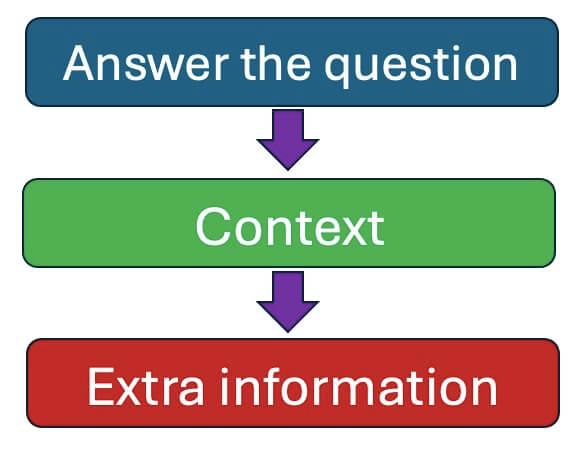

| Hi Lenah, Your content (answering the question) and organisation are generally ok, even though a bit mechanical. But you have very noticeable problems with grammar. You need to fix this if you want to achieve a good IELTS score. |

Band 7+ eBooks

"I think these eBooks are FANTASTIC!!! I know that's not academic language, but it's the truth!"

Linda, from Italy, Scored Band 7.5

Bargain eBook Deal! 30% Discount

All 4 Writing eBooks for just $25.86 Find out more >>

IELTS Modules:

Other resources:.

- Band Score Calculator

- Writing Feedback

- Speaking Feedback

- Teacher Resources

- Free Downloads

- Recent Essay Exam Questions

- Books for IELTS Prep

- Useful Links

Recent Articles

Selling a Mobile Phone to a Friend

Sep 15, 24 02:20 AM

Tips and Technique for IELTS Speaking Part 1

Sep 14, 24 02:41 AM

Grammar in IELTS Listening

Aug 22, 24 02:54 PM

Important pages

IELTS Writing IELTS Speaking IELTS Listening IELTS Reading All Lessons Vocabulary Academic Task 1 Academic Task 2 Practice Tests

Connect with us

Before you go...

30% discount - just $25.86 for all 4 writing ebooks.

Copyright © 2022- IELTSbuddy All Rights Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

- Criminal Procedure Research Topics Topics: 55

- Contract Law Research Topics Topics: 113

- Crime Investigation Topics Topics: 131

- Sex Offender Research Topics Topics: 54

- Criminal Justice Paper Topics Topics: 218

- Fourth Amendment Research Topics Topics: 49

- Intellectual Property Topics Topics: 107

- Criminal Behavior Essay Topics Topics: 71

- Juvenile Delinquency Research Topics Topics: 133

- Civil Law Topics Topics: 54

- Organized Crime Topics Topics: 52

- Criminology Research Topics Topics: 163

- Court Topics Topics: 140

- Supreme Court Paper Topics Topics: 87

- Drug Trafficking Research Topics Topics: 52

153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers

Welcome to our list of prison research topics! Here, you will find a vast collection of corrections topics, research papers ideas, and issues for group discussion. In addition, we’ve included research questions about prisons related to mass incarceration and other controversial problems.

🏆 Best Essay Topics on Prison

✍️ prison essay topics for college, 👍 good prison research topics & essay examples, 🎓 controversial corrections research topics, 💡 hot corrections topics for research papers, ❓ prison research questions.

- Overcrowding in Prisons and Its Impact on Health

- Prisons Are Ineffective in Rehabilitating Prisoners

- Prison Reform in the US Criminal Justice System

- The Stanford Prison Experiment

- How Education in Prisons Help Inmates Rehabilitate

- Prison System in the United States

- American Prisons as Social Institutions

- Prisons as a Response to Crimes Prisons are not adequate measures for limiting long-term crime rates or rehabilitating inmates, yet other alternatives are either undeveloped or too costly to ensure public safety.

- Mass Incarceration in American Prisons This research paper describes the definition of incarceration and focuses on the reasons for imprisonment in the United States of America.

- The Comfort and Luxury of Prison Life The main aims of the penal system are the rehabilitation of criminals and the reform of their behavior to make them model citizens as well as the deterrence of crime in society.

- American Prison Systems and Areas of Improvement The current operation of the prison system in America can no longer be deemed effective, in the correctional sense of this word.

- The Issue of Overcrowding in the Prison System Similar to terrorist attacks and the financial recession, jail overcrowding is an international issue that concerns all countries, regardless of their status.

- Alcatraz Prison and Its History With Criminals Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary famously referred to as “The Rock”, served as a maximum prison from 1934-1963. It was located on Alcatraz Island.

- The Electronic Monitoring of Offenders Released From Jail or Prison The paper analyzes the issue of electronic monitoring for offenders who have been released from prison or jail.

- Prison System Issues: Mistreatment and Abuse This research paper suggests solutions to the issue of prisoner abuse by exploring the causes of violence and discussing various types of assault in the prison system.

- Prison Staffing and Correctional Officers’ Duties The rehabilitative philosophy in corrective facilities continually prompts new reinforced efforts to transform inmates.

- Prison Makes Criminals Worse This paper discusses if prisons are effective in making criminals better for society or do they make them worse.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment Review The video presents an experiment held in 1971. In general, a viewer can observe that people are subjected to behavior and opinion change when affected by others.

- Discrimination in Prison Problem The problem of discrimination requires a great work of social workers, especially in such establishments like prisons.

- Prison Culture: Term Definition There has been contention in the area of literature whether prison culture results from the environment within the prison or is as a result of the culture that inmates bring into prison.

- Basic Literacy and School-to-Prison Pipeline Basic literacy is undoubtedly important for students to be successful in school and beyond, but it is not the only factor in stemming the school-to-prison pipeline.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment Analysis Abuse between guards and prisoners is an imminent factor attributed to the differential margin on duties and responsibilities.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment’s Historical Record The Stanford Prison Experiment is a seminal investigation into the dynamics of peer pressure in human psychology.

- The Lucifer Effect: Stanford County Prison In 1971, a group of psychologists led by Philip Zimbardo invited mentally healthy students from the USA and Canada, selected from 70 volunteers, to take part in the experiment.

- The Prison Effect Based on Philip Zimbardo’s Book This paper explores the lessons that can be learned from Philip Zimbardo’s book “The Lucifer Effect” and highlights the experiment’s findings and their implications.

- Ethical Decision-Making for Public Administrators at Abu Ghraib Prison The subject of prisoner mistreatment at Abu Ghraib Prison has garnered global attention and a prominent role in arguments over the Iraq War.

- Bruce Western’s Book Homeward: Life in the Year After Prison The book by Bruce Western Homeward: Life in the Year after Prison provides different perspectives on the struggles that ex-prisoners face once released from jail.

- Psychology: Zimbardo Prison Experiment Despite all the horrors that contradict ethics, Zimbardo’s research contributed to the formation of social psychology. It was unethical to conduct this experiment.

- Economic Differences in the US Prison System The main research question is, “What is the significant difference in the attitude toward prisoners based on their financial situation?”

- Transgender People in Prisons: Rights Violations There are many instances of how transgender rights are violated in jails: from misgendering from the staff and other prisoners to isolation and refusal to provide healthcare.

- The Prison-Based Community and Intervention Efforts The prison-based community is a population that should be supported in diverse spheres such as healthcare, psychological health, social interactions, and work.

- The Canadian Prison System: Problems and Proposed Solutions The state of Canadian prisons has been an issue of concern for more than a century now. Additionally, prisons are run in a manner that does not promote rehabilitation.

- Prison Population by Ethnic Group and Sex Labeling theory, which says that women being in “inferior” positions will get harsher sentences, and the “evil women hypothesis” are not justified.

- The State of Prisons in the United Kingdom and Wales Since 1993, there has been a steady increase in the prison population in the UK, hitting a record highest of 87,000 inmates in 2012.

- Drug Abuse Demographics in Prisons Drug abuse, including alcohol, is a big problem for the people contained in prisons, both in the United States and worldwide.

- Norway Versus US Prison and How They Differ The paper states that the discrepancies between the US and Norwegian prison systems can be influenced or determined by various factors.

- My Prison System: Incarceration, Deterrence, Rehabilitation, and Retribution The prison system described in the paper belongs to medium-security prisons which will apply to most types of criminals.

- The Criminal Justice System: The Prison Industrial Complex The criminal justice system is the institution which is present in every advanced country, and it is responsible for punishing individuals for their wrongdoings.

- Penal Labor in the American Prison System The 13th Amendment allows for the abuse of the American prison system. This is because it permits the forced labor of convicted persons.

- Mental Health Institutions in Prisons Mental institutions in prisons are essential and might be helpful to inmates, and prevention, detection, and proper mental health issues treatment should be a priority in prisons.

- Private and Public Prisons’ Functioning The purpose of this paper is to discuss the functioning of modern private and public prisons. There is a significant need to change the approach for private prisons.

- “Picking Battles: Correctional Officers, Rules, and Discretion in Prison”: Research Question The “Picking Battles: Correctional Officers, Rules, and Discretion in Prison” aims to define the extent to which correctional officers use discretion in their work.

- Understanding Recidivism in America’s Prisons One of the main issues encountered by the criminal justice system remains recidivism which continues to stay topical.

- Researching of the Reasons Prisons Exist While prisons are the most common way of punishing those who have committed a crime, the efficiency of prisons is still being questioned.

- “Episode 66: Yard of Dreams — Ear Hustle’’: Sports in Prison “Episode 66: Yard of dreams — Ear hustle’’ establishes that prison sports are an important aspect of transforming the lives of prisoners in the correctional system.

- The Concept of PREA (Prison Rape Elimination Act) Rape remains among the dominant crimes in the USA; almost every minute an American becomes a victim of it. The problem is especially acute in penitentiaries.

- Recidivism in the Criminal Justice: Prison System of America The position of people continuously returning to prisons in the United States is alarming due to their high rates.

- Prison’s Impact on People’s Health The paper explains experts believe that the prison situation contributes to the negative effects on the health of the convicted person.

- Prisons and the Different Security Levels Prisons are differentiated with regard to the extent of security, including supermax, maximum, medium, and minimum levels. This paper discusses prison security levels.

- Prisons in the United States In the present day, prisons may be regarded as the critical components of the federal criminal justice system.

- Understanding the U.S. Prison System This study will look at the various issues surrounding the punishment and rehabilitative aspects of U.S. prisons and determine what must be done to improve the system.

- American Criminal Justice System: Prison Reform Public safety and prison reform go hand-in-hand. Rethinking the way in which security is established within society is the first step toward the reform.

- Private Prisons: Review In the following paper, the issues that are rife in connection with contracting out private prisons will be examined along with the pros and cons of private prisons’ functioning.

- Women Serving Time With Their Children: The Challenge of Prison Mothers The law in America requires that mothers stay with their children as a priority. Prisons have therefore opened nurseries for children of mothers who are serving short terms.

- Arkansas Prison Scandals Regarding Contaminated Blood A number of scandals occurred around the infamous Cummins State Prison Farm in Arkansas in 1967-1969 and 1982-1983.

- Early Prison Release to Reduce a Prison’s Budget The primary goal of releasing nonviolent offenders before their sentences are finished is cutting down on expenses.

- State Prison System v. Federal Prison System The essay sums that the main distinction between these two prison systems is based on the type of criminals it handles, which means a difference in the level of security employed.

- Prisons in the United States Analysis The whole aspect of medical facilities in prisons is a very complex issue that needs to be evaluated and looked at critically for sustainability.

- Sex Offenders and Their Prison Sentences Both authors do not fully support this sanction due to many reasons, including medical, social, ethical, and even legal biases, where the latter is fully ignored.

- Security Threat Groups: The Important Elements in Prison Riots Security Threat Groups appear to be an a priori element of prison culture, inspired and cultivated by its fundamental principles of power.

- Criminal Punishment, Inmates on Death Row, and Prison Educational Programs This paper will review the characteristics of inmates, including those facing death penalties and the benefits of educational programs for prisoners.

- Prison System for a Democratic Society This report is designed to transform the corrections department to form a system favorable for democracy, seek to address the needs of different groups of offenders.

- Healthcare Among the Elderly Prison Population The purpose of this article is to address the ever-increasing cost of older prisoners in correctional facilities.

- Women’s Issues and Trends in the Prison System The government has to consider the specific needs of the female population in the prison system and work on preventing incarceration.

- What Makes Family Learning in Prisons Effective? This paper aims to discuss the family learning issue and explain the benefits and challenges of family learning in prisons.

- Overcrowding in Jails and Prisons In a case of a crime, the offender is either incarcerated, placed on probation or required to make restitution to the victim, usually in the form of monetary compensation.

- Unethical and Ethical Issues in the Prison System of Honduras Honduras has some of the highest homicide rates in the world and prisons in Honduras are associated with high levels of violence.

- Prison Reform in the US Up until this day, the detention facilities remain the restricting measure common for each State. The U.S. remains one of the most imprisoning countries.

- Whether Socrates Should Have Disobeyed the Terms of His Conviction and Escaped Prison? Socrates wanted to change manners and customs, he denounced the evil, deception, undeserved privileges, and thereby he aroused hatred among contemporaries and must pay for it.

- The Role of Culture in the School-to-Prison Pipeline The school-to-prison pipeline is based on many social factors and cannot be recognized as only an outcome of harsh disciplinary policies.

- Psychological and Sociological Aspects of the School-to-Prison Pipeline The tendency of sending children to prisons is examined from the psychological and sociological point of view with the use of two articles regarding the topic.

- School-to-Prison Pipeline: Roots of the Problem The term “school-to-prison pipeline” refers to the tendency of children and young adults to be put in prison because of harsh disciplinary policies within schools.

- US Prisons Review and Recidivism Prevention This research paper will focus on prison life in American prisons and the strategies to decrease recidivism once the inmates are released from prison.

- Administrative Segregation in California Prisons In California prisons, administrative segregation is applied to control safety as well as prisoners who are disruptive within the jurisdiction.

- Meditation in American Prisons from 1981 to 2004 Staggering statistics reveal that the United States has the highest rate of imprisonment of any country in the world, with the cost of imprisonment of this many people is now at twenty-seven billion dollars.

- How ”Prison Life” Affects Inmates Lifes As statistics indicate, 98% of those released from American prisons, after having served their sentences, do not consider themselves being “corrected”.

- Impact of the Stanford Prison Experiment Have on Psychology This essay will begin with a brief description of Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment then it will move to explore two main issues that arose from the said experiment.

- Use of Contingent Employees at the Federal Bureau of Prisons Contingent employment is a staffing strategy that the Federal Bureau of Prisons can use to address its staffing needs as well as achieve its budgetary target.

- Privatization of Prisons in the US, Australia and UK The phenomenon of modern prison privatization emerged in the United States in the mid-1980s and spread to Australia and the United Kingdom from there.

- Death Penalty from a Prison Officer’s Perspective The death penalty can be considered as an ancient form of punishment in relation to the type of crime that had been committed.

- Rehabilitation Programs Offered in Prisons The paper, am going to try and analyze some of the rehabilitation programs which will try to deter the majority of the inmates from been convicted of many crimes they are involved in.

- Prison Reform: Rethinking and Improving The topic of prison reform has been highly debated as the American Criminal Justice System has failed to address the practical and social challenges.

- Recidivism in American Prisons At present, recidivism is a severe problem for the United States. Many prisoners are released from jails but do not change their criminal behavior due to a few reasons.

- The Grizzly Conditions Prisoners Endure in Private Prisons The present paper will explore the issue of these ‘grizzly’ conditions in public prisons, arguing that private prisons need to be strictly regulated in order to prevent harm to inmates.

- Evaluation of the Stanford Prison Experiment’ Role The Stanford Prison Experiment is a study that was conducted on August 20, 1971 by a group of researchers headed by the psychology professor Philip Zimbardo.

- Women in Prison in the United States: Article and Book Summary A personal account of a woman prisoner known as Julie demonstrates that sexual predation/abuse is a common occurrence in most U.S. prisons.

- Prison Life in Nineteenth-Century Massachusetts In the article Larry Goldsmith has attempted to provide a detailed history of prison life and prison system during the 19th century.

- Prison Crowding in the US Most prisons in the United States and other parts of the world are overcrowded. They hold more prisoners that the initial capacity they were designed to accommodate.

- School-to-Prison Pipeline in Political Aspect This paper investigates the school-to-prison pipeline from the political point of view using the two articles concerning the topic.

- School-to-Prison Pipeline in American Justice This paper studies the problem by reviewing two articles regarding the school-to-prison pipeline and its aspects related to justice systems.

- Prison Population and Healthcare Models in the USA This paper focuses on the prison population with a view to apply the Vulnerable Population Conceptual Model, and summarizes US healthcare models.

- Prisoners’ Rights and Prison System Reform Criminal justice laws are antiquated and no longer serve their purposes. Instead, they cause harms to society, Americans and cost taxpayers billions of dollars.

- ICE Detention Surge: Impact of Legislative Changes and Border Security The issue of contracting the private prisons for accommodating the inmates has been challenged by various law suits over the quality of service that this companies offer to the inmates.

- Drugs and Prison Overcrowding There are a number of significant sign of the impact that the “war on drugs” has had on the communities in the United States.

- Prison Dog Training Program by Breakthrough Buddies

- Prison Abuse and Its Effect On Society

- The Truth About the Cruelty of Privatized Prison Health Care

- Prison Incarceration and Its Effects On The United States

- The United States Crime Problem and Our Prison System

- Prison Overcrowding and Its Effects On Living Conditions

- General Information about Prison and Capital Punishment Impact

- Problems With The American Prison System

- Prison and County Correctional Faculties Overcrowding

- People Who Commit Murder Should Be A Prison For An Extended

- African American Men and The United States Prison System

- Prison Gangs and the Community Responsibility System

- Prison Overcrowding and Its Effects On The United States

- Prison Should Not Receive Free College Education

- Pregnant Behind Bars and The United States Prison System

- Prison Life and Strategies to Decrease Recidivism

- Penitentiary Ideal and Models Of American Prison

- The Various Rehabilitation and Treatment Programs in Prison

- Prison and Mandatory Minimum Sentences

- Prisoner Visit and Rape Issue In Thai Prison

- Private Prisons Are Far Worse Than Any Maximum Security State Prison

- Prison Gangs and Their Effect on Prison Populations

- Overview of Prison Overcrowding and Staff Violence

- Classification and Prison Security Levels

- Prison and Positive Effects Rehabilitation Assignment

- Can Prison Deter Crime?

- What Are the Two Theories Regarding How Inmate Culture Becomes a Part of Prison Life?

- What Prison Is Mentioned in the Movie “Red Notice”?

- What’s the Worst Prison in Tennessee?

- What Causes Students to Enter the School of Prison Pipeline?

- How Can the Prison System Rehabilitate Prisoners So That They Will Enter the Society as Equals?

- Should Prison and Jail Be the Primary Service Provider?

- How Can Illegal Drugs Be Prevented From Entering Prison?

- How Does the Prison System Treat Trans Inmates?

- What Is the Deadliest Prison in America?

- Should Prison and Death Be an Easy Decision for a Court?

- Why Is It Called Black Dolphin Prison?

- Does Prison Strain Lead to Prison Misbehavior?

- Why Is the American Prison System Failing?

- What Country Has the Best Prison System?

- Does Prison Work for Offenders?

- Should Prison for Juveniles Be a Crime?

- What Is the Most Infamous Prison in America?

- What Is the World’s Most Secure Prison?

- What Do Russian Prison Tattoos Mean?

- What Causes Convicted Felons to Commit Another Crime After Release From Prison?

- What Are the Implications of Prison Overcrowding and Are More Prisons the Answer?

- Can Private Prisons Save Tax Dollars?

- Is Incarceration the Answer to Crime in Prison?

- What Are Prison Conditions Like in the US?

- Who Escaped From Brushy Mountain Prison?

- Why Does the Public Love Television Show, Prison Break?

- What Is the Scariest Prison in the World?

- When Did Brushy Mountain Prison Close?

- Which State Has the Most Overcrowded Prison?

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, December 21). 153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/prison-essay-topics/

"153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers." StudyCorgi , 21 Dec. 2021, studycorgi.com/ideas/prison-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers'. 21 December.

1. StudyCorgi . "153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers." December 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/prison-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers." December 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/prison-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers." December 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/prison-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Prison were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 24, 2024 .

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Rehabilitation Programs — Prison Reform

Prison Reform

- Categories: Rehabilitation Programs

About this sample

Words: 627 |

Published: Mar 13, 2024

Words: 627 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Nursing & Health

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1049 words

2 pages / 759 words

4 pages / 1596 words

8 pages / 3463 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Rehabilitation Programs

Drug addiction is a complex and pervasive issue that affects millions of individuals worldwide. It not only harms the individual struggling with addiction but also has far-reaching consequences for their families, communities, [...]

The question of whether criminals deserve a second chance is a complex and contentious issue that lies at the intersection of criminal justice, ethics, and social policy. This essay delves into the arguments surrounding this [...]

The question of whether ex-offenders should be given a second chance in society is a contentious and morally complex issue that sparks debates about rehabilitation, recidivism, and social responsibility. As the criminal justice [...]

Recidivism, or the tendency for a convicted criminal to reoffend, is a significant issue in the criminal justice system. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, approximately 68% of released prisoners are rearrested [...]

Culture is the qualities and learning of a specific gathering of individuals, enveloping dialect, religion, cooking, social propensities, music and expressions. There is an immaterial esteem which originates from adapting in [...]

In recent times there is a lot of emphasis on the importance of energy rehabilitation of the housing stock of our cities, giving more weight to the renovation of existing neighborhoods in front of the construction of new [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Essays on Prison

Faq about prison.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Why Write About Life in Prison?

Because every story needs hope..

This essay is excerpted from The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting A Writer’s Life in Prison, a recently released collection of essays from Haymarket Book and PEN America. Edited by PEN America’s Director of Prison and Justice Writing, Caits Meissner, the book weaves together insights from over 50 justice-involved contributors and their allies to offer inspiration and resources for creating a literary life in prison.

It started out just another day in prison: I shuffled the deck for a game of spades. My opponents had either been cheating or were having one hell of a lucky streak. Or maybe I just sucked at stacking the deck. I was certain I’d gotten all the cards just where I’d wanted them, when everyone stopped talking, eyes wide.

With my back to the window, I smelled the acrid stench of old insulation and smoldering cloth before turning toward the flames. Outside, grown men with faces covered in towels and T-shirts ran every which way. Prisoners were laying waste to the building’s weak points: the windows and doors. I’d later hear that some officers—fearing for their own safety—opened doors and stood back as their prisoners revolted in response to the warden’s lockdown orders. A billowy plume of smoke rose from where the chow hall used to be. A brick exploded against the metal grate barricading the window, and glass shards cascaded through the room. As my opponents rushed out into the chaos, the cards fell to the floor, the king of spades staring up.

The entire prison began to riot.

The year was 2009. The aftermath was Kentucky’s costliest riot in history. A friend of mine asked if I could help him put the experience into words for his family. For the first time since my imprisonment, I sat down to capture the havoc and devastation on paper. With pen to paper, my words flowed like the tears I was too ashamed to cry.

I’d never before been asked to describe the hell of prison. Why had I resisted depicting my environment for so long? I’d always wanted to be a creator of worlds, an author, an artist with words. Only somewhere along the way, I’d become convinced I wasn’t smart, educated, or articulate enough to say anything someone else would ever give a damn to hear. My dream of being an author was beat down by the poverty I was raised in, my inability to focus on my teachers, their lessons, and my grades, and eventually by the drug addiction I used to mask my inadequacies.

Three years into my incarceration, I was asked, “When you were little, what did you want to be when you grew up?”

It was then I decided to do something different. My pursuits turned to writing. I’d ask any and everyone for help. I’d finally dream. I’d change! But there was the nagging thought: Would anything I put down on the page make a difference? It was discomforting to not know where to begin, or what I wished to say.

Who was I as a writer? I found myself emulating all of my favorite authors in an attempt to locate my voice. But everything I wrote received the same critiques. Despite my imitation, I wasn’t making the progress I wanted. I still needed to work on my dialogue, characters, and plots. Discouraged, I stopped showing anyone my work. For a time, I stopped writing altogether.

It was only after my success with the riot piece that I felt comfortable enough to want people to read my work again. I felt validated, even if only temporarily. By then, the piece had been published on prisonwriters.com, and now all I had to do was wait. Someone would recognize my greatness, I thought to myself. And someone did—just not in the way I’d imagined it.

The friend who I’d written the riot piece for signed me up to join a group from Pioneer Playhouse, a local theater bringing the arts to prison. I was less than thrilled. Though I had zero interest in acting or writing plays, the prison offered nothing else.

I took the risk and joined the Voices Inside program.

“Write about what you know,” said the instructor. “Write from the gut.”

“I’m not writing about prison. Nobody gives a damn about prison,” I replied.

As it turned out, though my prison riot piece had been published, aside from pats on the back from a few of my fellow inmates and a small fifteen-dollar payment for the article, no one else said a thing about it. I’d bled on the page, and no one seemed to care, or even notice. The other twenty inmates of the very first Voices Inside class all agreed—no one wanted to write about the hell we all woke up to every morning. Instead, we showed up with our knockoffs of popular sitcoms, SNL skits, and all too many thinly veiled retellings of Romeo and Juliet.

The work was uninspired. The plays we would go on to write and perform in class all suffered greatly for our avoidance. With excuses of writer’s block, procrastination, and sheer refusal, we were lying to ourselves.

In attempting to tell stories—any stories—to avoid the topic of prison, we weren’t being true to our stories. I decided to set down the heavy sack of shame that I’d lugged around everywhere since my conviction. I wrote a new play in which I spoke of my own incarceration, not as something that had taken my life from me, but as something that had allowed me the time, separation, freedom to examine “my life.”

I wasn’t dead. None of us were. And though we’d all been stripped away from our families, our comforts, our routines and were confined to this “new normal,” our lives had not come to an end.

My first prison play involved the very people I’d spend the next twenty-five years locked away from: my children. With myself as the protagonist, I used my children’s hypothetical questions, blame, and confusion over my absence as the antagonist to reveal every truth I’d once steered clear of. Ultimately, guilt and innocence aside, it was my own poor choices that had put me in a prison of my own making.

I staged the play in the crowded classroom we used each week. Desks were moved aside to make an improvised auditorium with a few rows of plastic chairs. The play took place in the span of a visit with my now-grown children—strangers to me, with the names and once-familiar faces of the young people they’d been fifteen years before.

I wrote them as tragic characters who’d missed out on the father who had never put down roots, never truly loved their mother, never even attempted to be the man his children needed him to be. In the play, my daughter, the eldest, arrived on the scene to confront me with her anger. How could I ever leave her alone with two small brothers and a drug addict for a mother? Had I been the one to put the pipe to her mother’s lips, the needle in her veins? Did I know about the overdoses? All the strange men who’d found their way into my daughter’s bedroom in the middle of the night? Did I know all of the pain my being incarcerated had caused? Was I happy? Did I know all of the terrible things my children had grown up hearing about me? Did I know?

The man playing my daughter slapped me in the face with her last question before rushing offstage in tears. A voice from the audience called out: “Fucking go after her, man!” But the play ended with my character being restrained by an officer’s single hand.

Afterwards, I sat devastated and exposed. But as I glanced around the room, everyone’s resentment toward the man playing the officer was clear. I could feel them stewing on the same question. How do we begin to comfort the loved ones our decisions have taken us away from?

“That child needed her father,” said the man beside me. “I hate prison,” he said, placing his own comforting hand on my shoulder. “That really happens.”

Eleven years later, I still hear my fellow prisoners complain of having to share the details with those in their lives who know nothing about the realities of prison. No one wants to relive the grief of their incarceration. Ripping off scabs is painful. Their reticence is valid. I am patient. They have to find the courage on their own terms, within their own voices.

Why write about prison? Every story needs hope.

In our stories, we may have started out the murderers, rapists, thieves, and addicts, the monsters, the bad guys, the adversaries, the villains, the defendants, but prison does not have to be the end of our tale. If we don’t write our own endings, we hand our pens over to the legislators, owners of privatized prisons, and propagators of the lies behind mass incarceration.

I write about prison because there are more people in prisons in America than populate some small countries.

Because my experiences are the experiences of countless others. I write because there is truth in our stories that cannot, must not, be denied: the separation from our families, the toll on our loved ones, all the wasted time, the warehousing of our bodies, and our fruitless efforts to prevail against a flawed reality of incarceration.

That is the story I dare everyone to acknowledge. And only people behind bars can tell it as it truly is.

Prison Banned Books Week: Mark Twain Goes to Prison

"I treated each book I examined like it was a precious gem."

Kelly Jensen

Kelly is a former librarian and a long-time blogger at STACKED. She's the editor/author of (DON'T) CALL ME CRAZY: 33 VOICES START THE CONVERSATION ABOUT MENTAL HEALTH and the editor/author of HERE WE ARE: FEMINISM FOR THE REAL WORLD. Her next book, BODY TALK, will publish in Fall 2020. Follow her on Instagram @heykellyjensen .

View All posts by Kelly Jensen

This essay is part of a series to raise awareness during the second annual Prison Banned Books Week. Each essay, written by a currently incarcerated person, details the author’s experience of reading on prison tablets. Because every one of the 52 carceral jurisdictions in the country have different prison telecom contracts and censorship policies, it’s important to hear from incarcerated people across the country.

Single-state prison systems censor more books than all state schools and libraries combined. Recently, prisons and jails have been contracting with private telecom companies to provide tablets to detained and incarcerated people. Tablets have been used to curtail paper literature under specious claims that mail is the primary conduit of contraband. Most also have highly limited content. In many states, accessing the content is costly, despite companies acquiring these titles for free. This inaccessible and outdated reading material is used to justify preventing people from receiving paper literature and information.

This year, the organizers and supporters of Prison Banned Books Week encourage libraries to follow the example of San Francisco Public Library, which recently extended their catalog to local prisons and jails.

To learn more, visit the Prison Banned Books Week website or purchase a copy of Books through Bars: Stories from the Prison Books Movement edited by Moira Marquis and Dave “Mac” Marquis.

You can read the first essay in this series, Free Prison Tablets Aren’t Actually Free by Ezzial Williams, right here . The second essay in this series, Uninspired Reading by Ken Meyers, is available here .

Thank you for signing up! Keep an eye on your inbox. By signing up you agree to our terms of use

Mark Twain Goes to Prison by Derek Trumbo

Nearly twenty years ago, when I first got to prison I never thought I would become a writer, read John Updike, Luigi Pirandello, have a tablet that allowed me to play games and listen to music, or debate the merit of an old Mark Twain quote. Yet I here I am.

Entering the prison library as a fish or newbie, I was astounded to find so many books on the shelves, and to notice how reverently the other prisoners treated them. On my first day, I was shocked to see an older prisoner chastise a younger man for cracking the spine of a larger book he was perusing. “Young man, don’t do that. Don’t crack the spine on that book. It causes the pages to fall out. What we’ve got, we’ve got to take care of.” When the younger prisoner didn’t scoff at the older prisoner’s advice, I figured I’d best follow suit. I treated each book I examined like it was a precious gem.

I searched the shelves for Stephen King and anything else horror I could find. All I could find was a dog eared copy of IT. I’d read IT a few times, and watched the movie so many times I could practically quote it. There appeared to be only three other guys in line at the counter, so I took the book to the checkout and began to read as I waited. There were somewhere between four to ten other people in line doing the same thing I was doing. The man in front of me changed spots with two other guys who rushed up with books in their hands once they spotted me walk up. “I’m holding their spot,” said the guy ahead of me. “It’s called good looking out. These guys are super slow round here.” I could only nod my head, and step back, as the line of four prisoners grew.

Holding a spot turned out to be a convenience for several of the other guys in line as well. A laminated quote was hanging up beside the checkout counter, and I read it as the prisoners in line waited for the prisoners checking out their books took their sweet time to do so. The quote said, “When the rapture comes I’d rather be in Kentucky. Everything happens twenty years later there…” — Mark Twain.

By the time I got to the checkout counter and was able to place my book on the desk — the spot holders ahead of me finally ran out of friends to look out for — I’d already read nearly an entire chapter. That’s when I saw the plethora of boxes and index cards the prisoners behind the counter had to go through to find the book I wanted to check out. The man behind the counter took my book and searched the boxes for the corresponding checkout card. “I can’t find the card,” he finally told me. “Which mean this book is already checked out. You’ll have to find another book.”

Beside the Mark Twain quote was a small sign: No checkout card, no book. I returned the book to the shelf where I’d found it, and returned to the dorm.

Many years later — nearly twenty to be exact — recalling the quote by Samuel Clemens–better known as Mark Twain–I couldn’t help but to smirk at how accurate his words were.

I was in need of a book on writing, and there wasn’t one in the eBooks library on my prison issued Securus tablet. It was time to make a trip to the prison library. Many things had changed over the years since I first stepped foot into the prison’s library. We had a riot in 2009 that burned much of the prison to the ground, including the library and all of its books. I’d become a writer, and I’d turned into the old prisoner who warned younger prisoners not to destroy the few good things we had. Noticing a young man about to rip another page from one of the few art books on the shelves, I asked him, “What happens when there aren’t any more pages left to rip out?” The young man said he was going to use the drawing for a tattoo design he was working on. The prison wouldn’t allow tattoo books or magazines to be sent in, and he didn’t have anyone to send him pictures on the stupid tablets. He ripped the page out anyway, and gave me a look that told me to mind my own damn business.

I sat down with a book on writing, and began to study. Today’s subject was theme. I turned to John Updike’s short story A and P. The young man sat down at the table across from me. “What you reading?” he asked. “A book on writing,” I said. “What for?” “Because the tablets don’t have anything about how to become a writer on them,” I explained. “Just like they don’t have anything on how to draw.” “I’m taping the page back in the book,” the young man said. “I guess I can just study it here. Um, what are you trying to learn?”

I told the young man about how I was working on incorporating the use of theme into my stories more, and how the theme of Updike’s particular story, A and P, is that vanity or false heroics can prove extremely costly in some situations. In good stories the theme is backed up by a string of events that lay out the plot and lead the reader to the conclusion in such a way that they feel satisfied. I showed the young man another story I was studying War by Luigi Pirandello, and explained how just the day before I’d studied how Pirandello set his story in the passenger compartment of a train leading them into the battlefields of Italy at the start of World War I.

“World War I? That had to be like a lifetime ago,” the young man said. “I bet that’s on the tablet.” I explained how the tablets eBooks library only has things that are in the public domain. Plenty of World War I, but no Updike or Pirandello. It has to be 70 years old or older.

“I had a real tablet on the streets, and I could use it for everything. What I’ve got now is a joke,” said the young man. “Do you think the prison will ever update it, or let us actually use the damn thing the way it’s supposed to be used? Theres no streaming, or magazines, or Audible. Nothing but high priced music, Game Boy-era video games, and old ass books from people I don’t know nothing about. I tried to look up urban fiction and it gave me Unknown Mexico. What’s the use? It’s like all they want me to do is play video games, listen to music, and get into trouble.”

I glanced at the checkout, and smiled. The Mark Twain quote and numerous boxes of index cards had been gone since the riot of 2009. Only recently had the prison switched over from index cards and updated the library system to use computers for book checkouts.

“Sooner or later,” I said. “At least we’ve got tablets now. We’ve got to make the best of what we have. This is Kentucky we’re talking about after all.”

Prison censorship is a topic that has been covered in depth here at Book Riot for many years. Take some time this week to dive into those posts, including:

- Ending Censorship Applies to Prisons, Too

- Why and How Censorship Thrives in Prisons

- Censorship in Prisons Is Part of Slavery’s Legacy

- The Ever-Growing Challenge of Getting Books into Prisons

- Taking From The Vulnerable: JPay, States Charge Incarcerated for Free Ebooks

You Might Also Like

- Death Penalty

- Children in Adult Prison

- Wrongful Convictions

- Excessive Punishment

Prison Conditions

- Legacy of Slavery

- Racial Terror Lynching

- Racial Segregation

- Presumption of Guilt

- Community Remembrance Project

- Hunger Relief

- Unjust Fees and Fines

- Health Care

- True Justice Documentary

- A History of Racial Injustice Calendar

- Donation Questions

124 results for "Prison"

Millions of Americans are incarcerated in overcrowded, violent, and inhumane jails and prisons that do not provide treatment, education, or rehabilitation. EJI is fighting for reforms that protect incarcerated people.

As prison populations surged nationwide in the 1990s and conditions began to deteriorate, lawmakers made it harder for incarcerated people to file and win civil rights lawsuits in federal court and largely eliminated court oversight of prisons and jails. 1 Meredith Booker, “ 20 Years Is Enough: Time to Repeal the Prison Litigation Reform Act ,” Prison Policy Initiative (May 5, 2016).

Today, prisons and jails in America are in crisis. Incarcerated people are beaten, stabbed, raped, and killed in facilities run by corrupt officials who abuse their power with impunity. People who need medical care, help managing their disabilities, mental health and addiction treatment, and suicide prevention are denied care , ignored, punished, and placed in solitary confinement. And despite growing bipartisan support for criminal justice reform, the private prison industry continues to block meaningful proposals. 2 The Sentencing Project, “ Capitalizing on Mass Incarceration: U.S. Growth in Private Prisons ” (2018).

Escalating Violence

Related Article

Alabama’s Prisons Are Deadliest in the Nation

Over the last decade, there has been a dramatic increase in the level of violence in Alabama state prisons.

Alabama’s prisons are the most violent in the nation. The U.S. Department of Justice found in a statewide investigation that Alabama routinely violates the constitutional rights of people in its prisons, where homicide and sexual abuse is common, knives and dangerous drugs are rampant, and incarcerated people are extorted, threatened, stabbed, raped, and even tied up for days without guards noticing.

Serious understaffing, systemic classification failures, and official misconduct and corruption have left thousands of incarcerated individuals across Alabama and the nation vulnerable to abuse, assaults, and uncontrolled violence. 3 Matt Ford, “ The Everyday Brutality of America’s Prisons ,” The New Republic (Apr. 5, 2019).

Denying Treatment

Related Resource

The Marshall Project

A tragic case in New York illustrates how prisons are failing to provide adequate mental health treatment.

More than half of all Americans in prison or jail have a mental illness. 4 Mental Health America, “ Access to Mental Health Care and Incarceration .”’ Prison officials often fail to provide appropriate treatment for people whose behavior is difficult to manage, instead resorting to physical force and solitary confinement, which can aggravate mental health problems.

More than 60,000 people in the U.S. are held in solitary confinement. 5 Liman Center for Public Interest Law & Association of State Correctional Administrators, “ Reforming Restrictive Housing: The 2018 ASCA-Liman Nationwide Survey of Time-in-Cell ” (Oct. 2018). They’re isolated in small cells for 23 hours a day, allowed out only for showers, brief exercise, or medical visits, and denied calls or visits from family members. Studies show that people held in long-term solitary confinement suffer from anxiety, paranoia, perceptual disturbances, and deep depression. Nationwide, suicides among people held in isolation account for almost 50% of all prison suicides, even though less than 8% of the prison population is in isolation. 6 Erica Goode, “ Solitary Confinement: Punished for Life,” New York Times (Aug. 4, 2015).

The Supreme Court signaled in 2011 that failing to provide adequate medical and mental health care to incarcerated people could result in drastic consequences for states. It found that California’s grossly inadequate medical and mental health care is “incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society” and ordered the state to release up to 46,000 people from its “horrendous” prisons. 7 ‘ Brown v. Plata , 563 U.S. 493 (2011).’

But states like Alabama continue to fall far below basic constitutional requirements. In 2017, a federal court found Alabama’s “ horrendously inadequate ” mental health services had led to a “skyrocketing suicide rate” among incarcerated people. The court found that prison officials don’t identify people with serious mental health needs. There’s no adequate treatment for incarcerated people who are suicidal. And Alabama prisons discipline people with mental illness, often putting them in isolation for long periods of time.

Tolerating Abuse

Related Case

The Murder of Rocrast Mack

A 24-year-old man was beaten to death by guards at Alabama’s Ventress Prison.

A handful of abusive officers can engage in extreme cruelty and criminal misconduct if their supervisors look the other way. When violent correctional officers are not held accountable, a dangerous culture of impunity flourishes.

The culture of impunity in Alabama, and in many other states, starts at the leadership level. The Justice Department found in 2019 that the Alabama Department of Corrections had long been aware of the unconstitutional conditions in its prisons, yet “little has changed.” In fact, the violence has gotten worse since the Justice Department announced its statewide investigation in 2016.

Similarly, ADOC failed to do anything about the “toxic, sexualized environment that permit[ted] staff sexual abuse and harassment” at Tutwiler Prison for Women despite “repeated notification of the problems.”

In the face of rising homicide rates, Alabama officials misrepresented causes of death and the number of homicides in the state’s prisons. The Justice Department reported that Alabama officials knew that staff were smuggling dangerous drugs into prisons. But rather than address staff corruption and illegal activity, state officials tried to hide the alarming number of drug overdose deaths in Alabama prisons by misreporting the data.

Enriching Corporations

No universal decline in mass incarceration.

Report from the Vera Institute of Justice shows “the specter of mass incarceration is alive and well.”

Mass incarceration is “an expensive way to achieve less public safety.” 8 Don Stemen, “ The Prison Paradox: More Incarceration Will Not Make Us Safer ,” Vera Institute of Justice (2017). It cost taxpayers almost $87 billion in 2015 for roughly the same level of public safety achieved in 1978 for $5.5 billion. 9 Bureau of Justice Statistics, “ Summary Report: Expenditure and Employment Data for the Criminal Justice System 1978 ” (Sept. 1980). Factoring in policing and court costs, and expenses paid by families to support incarcerated loved ones, mass incarceration costs state and federal governments and American families $182 billion each year. 10 Peter Wagner and Bernadette Rabuy, “ Following the Money of Mass Incarceration ,” Prison Policy Initiative (2017).

Rising costs have spurred some local, state, and federal policymakers to reduce incarceration. But private corrections companies are heavily invested in keeping more than two million Americans behind bars. 11 Eric Markowitz, “ Making Profits on the Captive Prison Market ,” The New Yorker (Sept. 4, 2016).

The U.S. has the world’s largest private prison population. 12 The Sentencing Project, “ Capitalizing on Mass Incarceration: U.S. Growth in Private Prisons ” (2018). Private prisons house 8.2% (121,420) of the 1.5 million people in state and federal prisons. 13 Jennifer Bronson & E. Ann Carson, “ Prisoners in 2017 ,” Bureau of Justice Statistics (Apr. 2019). Private prison corporations reported revenues of nearly $4 billion in 2017. 14 Peter Wagner and Bernadette Rabuy, “ Following the Money of Mass Incarceration,” Prison Policy Initiative (2017). The private prison population is on the rise , despite growing evidence that private prisons are less safe, do not promote rehabilitation, and do not save taxpayers money.

The fastest-growing incarcerated population is people detained by immigration officials. 15 Gretchen Gavett, “ Map: The U.S. Immigration Detention Boom ,” PBS Frontline (Oct. 18, 2011). The federal government is increasingly relying on private, profit-based immigration detention facilities . 16 Madison Pauly, “ Trump’s Immigration Crackdown is a Boom Time for Private Prisons ,” Mother Jones (May/June 2018). Private detention companies are paid a set fee per detainee per night, and they negotiate contracts that guarantee a minimum daily headcount, creating perverse incentives for government officials. Many run notoriously dangerous facilities with horrific conditions that operate far outside federal oversight. 17 Emily Ryo & Ian Peacock, “ The Landscape of Immigration Detention in the United States ,” American Immigration Council (Dec. 2018).

Private prison companies profit from providing services at virtually every step of the criminal justice process, from privatized fine and ticket collection to bail bonds and privatized probation services. Profits come from charging high fees for services like GPS ankle monitoring, drug testing, phone and video calls, and even health care. 18 In the Public Interest, “ Private Companies Profit from Almost Every Function of America’s Criminal Justice System ” (Jan. 20, 2016).

Many state and local governments have entered into expensive long-term contracts with private prison corporations to build and sometimes operate prison facilities. Since these contracts prevent prison capacity from being changed or reduced, they effectively block criminal justice and immigration policy changes. 19 Bryce Covert, “ How Private Prison Companies Could Get Around a Federal Ban ,” The American Prospect (June 28, 2019).

Featured Work

EJI is confronting the nation’s most deadly and overcrowded prison system by investigating, documenting, and filing federal lawsuits and complaints about conditions in Alabama’s prisons.

Challenging Violent Prison Culture

EJI is suing the Alabama Department of Corrections for failing to respond to dangerous conditions and a high rate of violence at St. Clair Correctional Facility.

Investigating Sexual Abuse

EJI exposed the widespread sexual abuse of women incarcerated at Tutwiler Prison for Women, leading to a federal investigation.

Exposing Corruption, Violence, and Abuse

EJI has documented severe physical and sexual abuse and violence perpetrated by correctional officers and officials in three Alabama prisons for men.

Related Articles

Fourth Homicide in Six Months at Alabama’s Limestone Prison

Another Alabama Man Killed at Ventress Prison

Third Homicide in Four Months at Alabama’s Limestone Correctional Facility

Another Alabama Prison Homicide at Donaldson Correctional Facility

Explore more in Criminal Justice Reform

Life Behind the Wall

| who are often called to help during wildfire season. |

| that on-screen depictions of prison life, particularly in the context of documentary and reality programming, play a significant role in shaping Americans’ impressions of incarceration. But TV shows tend to skip the daily routines of prison life—work, classes, watching television—in favor of conflict and extreme behavior. |

| , including shows titled “Jailbirds,” “I Am A Killer” and “Inside the World’s Toughest Prisons.” Reality shows can only film what they can get access to through prison officials and what their incarcerated subjects are willing to do on camera. Scripted dramas have far more leeway, and are often more violent as a result. While Netflix’s “Orange is the New Black” has been and dramatizing systemic injustice, shows like NBC’s “Law and Order: SVU” and HBO’s now defunct “Oz” make prison rape an inevitability—and often a punchline. |

| , is one of the best representations of the often lurid and contradictory fascination that prison holds over . The NYPD detectives on “Law and Order” rarely pass up an opportunity to weaponize prison gang violence or the threat of prison rape during the questioning of suspects. At the same time, entire episodes have been dedicated to exploring crucial prison issues like solitary confinement, transwomen in male-populated prisons, and pervasive sexual assault and coercion in women’s facilities. |

| . Prison accelerates the aging process, shortens life expectancy and makes prisoners and staff . And the effects of prison aren’t just physical. The stress, boredom and violence of prison can affect prisoners’ mental health. |

| “At the very least, prison is painful, and incarcerated persons often suffer long-term consequences from having been subjected to pain, deprivation, and extremely atypical patterns and norms of living and interacting with others.” |

| , and call it a form of torture. suggests that sustained isolation can increase levels of anxiety, depression, paranoia and PTSD. It can also exacerbate chronic physical health problems such obesity, high blood pressure and asthma and , even post-release. |

| on services in prison, like phone calls and commissary items. |

| and into a prisoner’s account. |

| each year. |

| profit from the prison system. Securus, one of the leading prison telecommunications companies, makes roughly in revenue. From 2004 to 2014 the company paid over to prison officials and state and local governments. |

| to see a doctor or nurse. Prison wages are so low that these fees can be the equivalent of a month’s earnings. |

| narrated by Michael K. Williams, illustrated by Molly Crabapple, and drawn from a huge collection of letters compiled by the American Prison Writing Archive. |

| many prisoners—and their families—call home. More than 63 percent of people in state prisons are locked up over 100 miles from their families, a from the Prison Policy Initiative found. Black and Latino people make up a disproportionate share of the prison population, but many prison towns are majority White. |

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

To help you get started, here are 103 prison essay topic ideas and examples: The effectiveness of prison as a form of punishment. The impact of incarceration on mental health. The role of prisons in reducing recidivism rates. The overcrowding crisis in prisons. The ethics of for-profit prisons. The impact of prison privatization on inmate rights.

Researching of Prisons in Corcoran. The present essay explains an ornate connection link between agriculture and prisons and discusses the influence of political and economic trends in the US from the 1970-s the 1990-s on some of the failures of […] Mass Incarceration: Prison System in America.

First, violence can be controlled through supervision and management. Second, there can be provision of adequate services in the prison. Thirdly, it can be ensured that the prison is serving its incarceration purpose. Another solution is the provision of gang members' segregation housing units.

Prison Essays. Some people think that the best way to reduce crime is to give longer prison sentences. Others, however, believe there are better alternative ways of reducing crime. Discuss both views and give your opinion. Day by day, the rate of crimes in the world is increasing rapidly and there are many ways both individuals and government ...

153 Prison Essay Topics & Corrections Topics for Research Papers. Welcome to our list of prison research topics! Here, you will find a vast collection of corrections topics, research papers ideas, and issues for group discussion. In addition, we've included research questions about prisons related to mass incarceration and other controversial ...

Get original essay. One of the key aspects of prison reform is the implementation of rehabilitation programs within correctional facilities. These programs aim to provide inmates with the necessary skills and resources to reintegrate into society upon their release. Research has shown that inmates who participate in educational and vocational ...

The issue of violent behavior is commonly associated with life in prison, and many inmates try to exhibit violent tendencies in a bid to ensure their survival. Prison subcultures are directly related to violent behavior in that there may be situations. One example is a situation whereby the gangs that have been formed in prison may not relate ...

Essays on Prison. Free essays on prison are online resources that provide insight into various topics related to prison, including the effects of incarceration on mental health, the privatization of prisons, and the impact of the prison industrial complex on society. These essays offer different perspectives on the issue, ranging from personal ...

According to research conducted by Hurd (2005: 26-27), prisons don't work at all. Increase in imprisonment doesn't reduce crime. He used England and Wales as an example. Number of prisoners increased from 44,000 to 60,000 from 1986 to 1997, but no reduction in crime was recorded.

This essay is excerpted from The Sentences That Create Us: Crafting A Writer's Life in Prison, a recently released collection of essays from Haymarket Book and PEN America. Edited by PEN America ...

Count times in prison are an imprecise science, from a convict's point of view. Sure, they start at the same times each day: 5 a.m., 11:30 a.m., 4 p.m., 9 p.m., and midnight. But when each one might end is anybody's guess. It's basically purgatory. On this particular day, I get lucky.

Pages: 4 Words: 1540. Prisons. Prison is a place where, for the protection of society, those found guilty of crimes are sent to be incarcerated. Prisons are a relative new invention, being created in the modern world, and therefore the social effects on inmates are not well-known.

Prisons And Prisons : Prisons Essay. Prisons are supposed to be good thing, but when so much trouble comes out of them it's hard to remember what they're there for. Criminals go in to be rehabilitated and to be able to come out as a better citizen. But when the prisons and jails effect that in a negative way things are not working the way ...

Each essay, written by a currently incarcerated person, details the author's experience of reading on prison tablets. Because every one of the 52 carceral jurisdictions in the country have different prison telecom contracts and censorship policies, it's important to hear from incarcerated people across the country.

As prison populations surged nationwide in the 1990s and conditions began to deteriorate, lawmakers made it harder for incarcerated people to file and win civil rights lawsuits in federal court and largely eliminated court oversight of prisons and jails. 1 Meredith Booker, "20 Years Is Enough: Time to Repeal the Prison Litigation Reform Act," Prison Policy Initiative (May 5, 2016).

People in prison are sicker than their peers on the outside, research shows. Prison accelerates the aging process, shortens life expectancy and makes prisoners and staff particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. And the effects of prison aren't just physical. The stress, boredom and violence of prison can affect prisoners' mental health.

How Atrocious Prisons Conditions Make Us All Less Safe. The American prison system seems designed to ensure that people return to incarceration instead of successfully reentering society. This essay is part of the Brennan Center's series examining the punitive excess that has come to define America's criminal legal system.

The disturbing fact in the United States is that today, the American. 'Correctional' system has the largest population of prisoners in the world. According to the U.S. Bureau of Justice statistics, "2,299,116 prisoners were held in federal or state prisons or in local jails" (2008, para 1) as on 30 June 2007. Such a large population has ...

Prison time can result in increased impulsiveness and poorer attentional control (Credit: Alamy) The researchers think the changes they observed are likely due to the impoverished environment of ...

The U.S. has seen a steady decline in the federal and state prison population over the last eleven years, with a 2019 population of about 1.4 million men and women incarcerated at year-end ...

prison, an institution for the confinement of persons who have been remanded (held) in custody by a judicial authority or who have been deprived of their liberty following conviction for a crime.A person found guilty of a felony or a misdemeanour may be required to serve a prison sentence.The holding of accused persons awaiting trial remains an important function of contemporary prisons, and ...

September 2, 2023. Illustration by Isabel Seliger. The first time I heard about Taylor Swift, I was in a Los Angeles County jail, waiting to be sent to prison for murder. Sheriffs would hand out ...

Social Psychology Issues: The Stanford Prison Experiment Essay. Social psychology examines how the personality, attitudes, motivations and actions of individuals are influenced by social groups. Researchers in the field have always been interested in the effects that social and environmental elements have on individuals' perceptions and behavior.

Scotland's papers: Prison overcrowding and Starmer under pressure. 21 hrs ago. Scotland. More. 23 Aug 2024. Scottish island recognised among world's best night skies.