100 Qualitative Research Titles For High School Students

Are you brainstorming for excellent qualitative research titles for your high school curriculum? If yes, then this blog is for you! Academic life throws a lot of thesis and qualitative research papers and essays at you. Although thesis and essays may not be much of a hassle. However, when it comes to your research paper title, you must ensure that it is qualitative, and not quantitative.

Qualitative research is primarily focused on obtaining data through case studies, artifacts, interviews, documentaries, and other first-hand observations. It focuses more on these natural settings rather than statistics and numbers. If you are finding it difficult to find a topic, then worry not because the high schooler has this blog post curated for you with 100 qualitative research titles that can help you get started!

Qualitative research prompts for high schoolers

Qualitative research papers are written by gathering and analyzing non-numerical data. Generally, teachers allot a list of topics that you can choose from. However, if you aren’t given the list, you need to search for a topic for yourself.

Qualitative research topics mostly deal with the happenings in society and nature. There are endless topics that you can choose from. We have curated a list of 100 qualitative research titles for you to choose from. Read on and pick the one that best aligns with your interests!

- Why is there a pressing need for wildlife conservation?

- Discuss the impacts of climate change on future generations.

- Discuss the impact of overpopulation on sustainable resources.

- Discuss the factors considered while establishing the first 10 engineering universities in the world.

- What is the contribution of AI to emotional intelligence? Explain.

- List out the effective methods to reduce the occurrences of fraud through cybercrimes.

- With case studies, discuss some of the greatest movements in history leading to independence.

- Discuss real-life scenarios of gender-based discrimination.

- Discuss disparities in income and opportunities in developing nations.

- How to deal with those dealing with ADHD?

- Describe how life was before the invention of the air conditioner.

- Explain the increasing applications of clinical psychology.

- What is psychology? Explain the career opportunities it brings forth for youngsters.

- Covid lockdown: Is homeschooling the new way to school children?

- What is the role of army dogs? How are they trained for the role?

- What is feminism to you? Mention a feminist and his/her contributions to making the world a better place for women.

- What is true leadership quality according to you? Explain with a case study of a famous personality you admire for their leadership skills.

- Is wearing a mask effective in preventing covid-19? Explain the other practices that can help one prevent covid-19.

- Explain how teachers play an important role in helping students with disabilities improve their learning.

- Is ‘E business’ taking over traditional methods of carrying out business?

- What are the implications of allowing high schoolers to use smartphones in classes?

- Does stress have an effect on human behavior?

- Explain the link between poverty and education.

- With case studies, explain the political instability in developing nations.

- Are ‘reality television shows’ scripted or do they showcase reality?

- Online vs Offline teaching: which method is more effective and how?

- Does there exist an underlying correlation between education and success? Explain with case studies.

- Explain the social stigma associated with menstruation.

- Are OTT entertainment platforms like Netflix and Amazon Prime beneficial in any other way?

- Does being physically active help reverse type 2 diabetes?

- Does pop culture influence today’s youth and their behavior?

- ‘A friend in need is a friend in deed.’ Explain with case studies of famous personalities.

- Do books have greater importance in the lives of children from weaker economic backgrounds? Explain in detail.

- Give an overview of the rise of spoken arts.

- Explain the problem of food insecurity in developing nations.

- How related are Windows and Apple products?

- Explore the methods used in schools to promote cultural diversity.

- Has social media replaced the physical social engagement of children in society?

- Give an overview of allopathic medicine in treating mental disorders.

- Explain if and how willpower plays a role in overcoming difficulties in life.

- Are third-world countries seeing a decline in academic pursuit? Explain with real-life scenarios.

- Can animals predict earthquakes in advance? Explain which animals have this ability and how they do it.

- Discuss if the education system in America needs to improve. If yes, list out how this can be achieved.

- Discuss democracy as a government of the people, by the people, and for the people.’

- Discuss the increasing rate of attention deficit disorder among children.

- Explain fun games that can help boost the morale of kids with dyslexia.

- Explain the causes of youth unemployment.

- Explain some of the ways you think might help in making differently-abled students feel inclusive in the mainstream.

- Explain in detail the challenges faced by students with special needs to feel included when it comes to accessibility to education.

- Discuss the inefficiency of the healthcare system brought about by the covid-19 pandemic.

- Does living in hostels instill better life skills among students than those who are brought up at home? Explain in detail.

- What is Advanced Traffic Management? Explain the success cases of countries that have deployed it.

- Elaborate on the ethnic and socioeconomic reasons leading to poor school attendance in third-world nations.

- Do preschoolers benefit from being read to by their parents? Discuss in detail.

- What is the significance of oral learning in classrooms?

- Does computer literacy promise a brighter future? Analyze.

- What people skills are enhanced in a high school classroom?

- Discuss in detail the education system in place of a developing nation. Highlight the measures you think are impressive and those that you think need a change.

- Apart from the drawbacks of UV rays on the human body, explain how it has proven to be beneficial in treating diseases.

- Discuss why or why not wearing school uniforms can make students feel included in the school environment.

- What are the effective ways that have been proven to mitigate child labor in society?

- Explain the contributions of arts and literature to the evolving world.

- How do healthcare organizations cope with patients living with transmissive medical conditions?

- Why do people with special abilities still face hardships when it comes to accessibility to healthcare and education?

- What are the prevailing signs of depression in small children?

- How to identify the occurrences and onset of autism in kids below three years of age?

- Explain how SWOT and PESTLE analysis is important for a business.

- Why is it necessary to include mental health education in the school curriculum?

- What is adult learning and does it have any proven benefits?

- What is the importance of having access to libraries in high school?

- Discuss the need for including research writing in school curriculums.

- Explain some of the greatest non-violent movements of ancient history.

- Explain the reasons why some of the species of wildlife are critically endangered today.

- How is the growing emission of co2 bringing an unprecedented change in the environment?

- What are the consequences of an increasing population in developing nations like India? Discuss in detail.

- Are remote tests as effective as in-class tests?

- Explain how sports play a vital role in schools.

- What do you understand about social activities in academic institutions? Explain how they pose as a necessity for students.

- Are there countries providing free healthcare? How are they faring in terms of their economy? Discuss in detail.

- State case studies of human lives lost due to racist laws present in society.

- Discuss the effect of COVID-19 vaccines in curbing the novel coronavirus.

- State what according to you is more effective: e-learning or classroom-based educational systems.

- What changes were brought into the e-commerce industry by the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Name a personality regarded as a youth icon. Explain his or her contributions in detail.

- Discuss why more and more people are relying on freelancing as a prospective career.

- Does virtual learning imply lesser opportunities? What is your take?

- Curbing obesity through exercise: Analyze.

- Discuss the need and importance of health outreach programs.

- Discuss in detail how the upcoming generation of youngsters can do its bit and contribute to afforestation.

- Discuss the 2020 budget allocation of the United States.

- Discuss some of the historic ‘rags to riches’ stories.

- What according to you is the role of nurses in the healthcare industry?

- Will AI actually replace humans and eat up their jobs? Discuss your view and also explain the sector that will benefit the most from AI replacing humans.

- Is digital media taking over print media? Explain with case studies.

- Why is there an increasing number of senior citizens in the elderly homes?

- Are health insurances really beneficial?

- How important are soft skills? What role do they play in recruitment?

- Has the keto diet been effective in weight loss? Explain the merits and demerits.

- Is swimming a good physical activity to curb obesity?

- Is work from home as effective as work from office? Explain your take.

Tips to write excellent qualitative research papers

Now that you have scrolled through this section, we trust that you have picked up a topic for yourself from our list of 100 brilliant qualitative research titles for high school students. Deciding on a topic is the very first step. The next step is to figure out ways how you can ensure that your qualitative research paper can help you grab top scores.

Once you have decided on the title, you are halfway there. However, deciding on a topic signals the next step, which is the process of writing your qualitative paper. This poses a real challenge!

To help you with it, here are a few tips that will help you accumulate data irrespective of the topic you have chosen. Follow these four simple steps and you will be able to do justice to the topic you have chosen!

- Create an outline based on the topic. Jot down the sub-topics you would like to include.

- Refer to as many sources as you can – documentaries, books, news articles, case studies, interviews, etc. Make a note of the facts and phrases you would like to include in your research paper.

- Write the body. Start adding qualitative data.

- Re-read and revise your paper. Make it comprehensible. Check for plagiarism, and proofread your research paper. Try your best and leave no scope for mistakes.

Wrapping it up!

To wrap up, writing a qualitative research paper is almost the same as writing other research papers such as argumentative research papers , English research papers , Biology research papers , and more. Writing a paper on qualitative research titles promotes analytical and critical thinking skills among students. Moreover, it also helps improve data interpretation and writing ability, which are essential for students going ahead.

Having a 10+ years of experience in teaching little budding learners, I am now working as a soft skills and IELTS trainers. Having spent my share of time with high schoolers, I understand their fears about the future. At the same time, my experience has helped me foster plenty of strategies that can make their 4 years of high school blissful. Furthermore, I have worked intensely on helping these young adults bloom into successful adults by training them for their dream colleges. Through my blogs, I intend to help parents, educators and students in making these years joyful and prosperous.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

139+ Best Qualitative Research Topics for High School Students

Explore exciting qualitative research topics for high school students. Find ideas that spark curiosity and make learning about human behavior and culture fun and engaging.

Ever wondered what makes people tick or how different cultures live? Qualitative research is a great way to explore these questions. It goes beyond numbers to dive into real-life stories and experiences.

This guide will help you start your journey into qualitative research, no matter your interests. Let’s uncover the fascinating stories and insights that this method can reveal!

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research Topics for High School Students PDF

What is qualitative research.

Qualitative research focuses on understanding people’s experiences and perspectives. It goes beyond numbers to explore the “why” and “how” of a situation.

Key features

- Exploratory: Finds new insights.

- In-depth: Provides detailed data.

- Subjective: Considers the researcher’s role.

- Contextual: Looks at social and cultural factors.

Common methods include

- Focus groups

Observations

- Document analysis

It helps us understand complex social issues and human behavior.

| : |

Qualitative Research Topics for High School Students

Check out qualitative research topics for high school students:-

Social Issues

- How Social Media Affects Teen Self-Esteem

- Student Experiences with School Bullying

- The Role of School Counselors in Mental Health

- Diversity in High Schools: Student Views

- Economic Disparities and Student Success

- Effectiveness of Anti-Bullying Programs

- Peer Pressure and Risk-Taking Behaviors

- School Policies for Students with Disabilities

- Gender Equality in Sports

- Impact of School Uniforms on Students

- Online vs. In-Person Learning: Student Views

- How Teacher Expectations Affect Performance

- Students with Learning Disabilities in Classrooms

- Extracurriculars and Academic Success

- Relevance of School Curriculum

- Impact of Student Feedback on Class Policies

- Fairness of Grading Systems

- Effect of Homework on Students

- Tech’s Role in Learning

- Peer Tutoring’s Impact on Learning

Health and Wellbeing

- Teen Views on Healthy Eating

- Physical Exercise and School Performance

- Stress and Coping Strategies for Students

- Importance of Sleep for Teens

- Attitudes Toward Substance Use

- Family Diets and Teen Eating Habits

- Mental Health Resources at School

- Body Image and Self-Esteem

- Schools and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion

- Sexual Health Education

Technology and Media

- Teens Using Social Media for News

- Video Games and Social Interaction

- Cyberbullying: Causes and Effects

- Media’s Influence on Teen Fashion

- Privacy and Security Online

- Tech’s Effect on Communication Skills

- Influencers and Teen Trends

- Digital Devices in Learning

- Screen Time and Health

- Streaming Services and Entertainment Choices

Culture and Identity

- Family Traditions and Teen Identity

- Cultural Heritage and Integration

- Impact of Cultural Festivals

- Navigating Multiple Cultural Identities

- Media’s Influence on Body Image

- Cultural Appropriation Views

- Religion’s Role in Teen Values

- Multicultural Education’s Impact

- Cultural Exchange Programs

- Language Barriers and Social Integration

Environment and Community

- Teens in Environmental Conservation

- Local Community Services and Resources

- Urban vs. Rural Living Effects

- Community Volunteer Work

- Schools and Environmental Issues

- Local Government and Teen Views

- Youth’s Role in Environmental Policies

- Green Spaces and Teen Wellbeing

- Community Events and Social Life

- Climate Change Awareness

Family Dynamics

- Family Structure and Academic Performance

- Parental Involvement in Education

- Single-Parent Family Experiences

- Family Communication and Conflict

- Role of Siblings in Teen Behavior

- Family Financial Issues and Stress

- Family Traditions and Teen Values

- Family Support Systems

- Parental Work Schedules and Social Life

- Parenting Styles and Effects

Career and Future Aspirations

- Career Exploration and Planning

- Impact of Internships on Career Choices

- Career Counseling Services

- Extracurriculars and Career Goals

- Job Shadowing and Work Experiences

- Career Fairs and Aspirations

- College vs. Vocational Training

- Part-Time Jobs and Academics

- Parental Expectations and Careers

- Entrepreneurship and Business Ownership

Arts and Creativity

- Creative Arts and Emotional Expression

- Importance of Arts Education

- Theater and Confidence

- Music’s Impact on Mood

- Creative Outlets and Self-Expression

- Art’s Role in Identity

- Creative Writing and Wellbeing

- Visual Arts and Critical Thinking

- Arts Integration in Curriculum

- Arts Festivals and Student Creativity

Consumer Behavior

- Brand Loyalty and Consumerism

- Advertising’s Effect on Purchases

- Sustainable and Ethical Choices

- Peer Pressure in Shopping

- Trends in Fashion and Tech

- Influencers and Consumer Preferences

- Economic Conditions and Spending

- Luxury Brands and Teens

- Online vs. In-Store Shopping

- Parental Influence on Purchases

Sports and Recreation

- Sports and Social Skills

- School Sports Programs and Team Spirit

- Recreational Activities and Stress

- Sports and Leadership Skills

- Physical Education Classes

- Competitive Sports and Mental Health

- Non-Traditional Sports and Activities

- Sports Injuries and Health

- Gender Equality in Sports Programs

- Sports and School Spirit

Personal Development

- Goal Setting and Achievement

- Self-Help Books and Personal Growth

- Time Management and Responsibilities

- Mentorship and Development

- Perceptions of Success and Failure

- Self-Reflection Practices

- Volunteering and Personal Growth

- Leadership Roles in School Projects

- Hobbies and Skill Development

- Accountability and Responsibility

Social Relationships

- Dynamics of High School Friendships

- Romantic Relationships and School Life

- Family Relationships and Social Support

- Peer Groups and Behavior

- Social Media’s Role in Relationships

- Friendships in Diverse Environments

- Importance of Social Skills

- Social Dynamics and Self-Esteem

- Peer Mentorship Programs

- Navigating Social Conflicts

Local and Global Issues

- Global Environmental Issues

- Local Community Initiatives

- Globalization and Local Cultures

- Youth Engagement in Humanitarian Efforts

- International News and Worldviews

- Local Government Policies and Teen Life

- Global Health Crises and Local Effects

- Youth Activism and Global Issues

- Global Economic Inequality

- International Events and Citizenship

Why is qualitative research important for high school students?

Qualitative research is great for high school students because it:

- Deepens Understanding: Explores complex issues in detail.

- Addresses Real-World Issues: Tackles relevant social problems.

- Builds Skills: Enhances observation, interviewing, and analysis.

- Boosts Critical Thinking: Encourages questioning and data interpretation.

- Improves Communication: Strengthens writing and speaking skills.

- Fosters Empathy: Helps understand different viewpoints.

- Prepares for College: Develops essential research skills.

It helps students become active learners and gain a better understanding of their world.

The benefits of conducting qualitative research

Qualitative research offers several key benefits:

Deeper Understanding

- Rich Data: Reveals detailed perspectives.

- Contextualization: Shows real-life situations.

- Exploration: Finds new phenomena.

Flexibility and Adaptability

- Open-ended: Adapts to new findings.

- Focused: Investigates specific topics.

- Participant-driven: Values participants’ input.

Theory Building

- Inductive Reasoning: Develops new theories.

- Contextual: Bases theories on real experiences.

- Knowledge Expansion: Adds to existing knowledge.

Enhanced Validity

- Thick Description: Offers detailed accounts.

- Triangulation: Combines data sources.

- Member Checking: Validates with participants.

These benefits show why qualitative research is valuable for deep insights and theory development.

Understanding Qualitative Research Methods

Let’s understand qualitative research methods:-

Observation: Watching and recording behavior.

- Participant: Joins the group being observed.

- Non-participant: Observes without joining.

- Interviews: Conversations to collect information.

Structured: Fixed questions.

- Semi-structured: Guided but flexible.

- Unstructured: Open-ended conversation.

Focus Groups: Group discussions for insights.

Document analysis: reviewing existing documents..

- Types: Texts, images, audio, video.

Case Studies: Detailed study of one person, group, or event.

These methods can be used alone or together to gather detailed data.

Choosing a Qualitative Research Topic

Check out the best tips to choose a qualitative research topic:-

Identify Interests

Find out what excites you. Think about issues or questions from your experiences and studies.

Develop a Research Question

- Make it specific and relevant.

- Example: Instead of “What is the impact of social media on teenagers?” ask “How does excessive Instagram use affect body image in teenage girls?”

Narrow Down the Topic

- Scope: Set limits (e.g., time, location).

- Feasibility: Ensure you can access the needed data.

- Relevance: Consider the research’s potential impact.

Consider Ethics

- Participant Rights: Keep privacy and confidentiality.

- Informed Consent: Get clear permission from participants.

- Minimize Harm: Protect participants from harm.

- Data Management: Secure your research data.

Following these steps will help you choose a research topic that is both meaningful and manageable.

Conducting Qualitative Research

Check out the best tips for conducting qualitative research:-

Data Collection Methods: Gather detailed data using

- Interviews: Structured, semi-structured, or unstructured conversations.

- Observations: Watching participants in their natural settings.

- Focus Groups: Group discussions to explore shared perspectives.

- Document Analysis: Reviewing existing documents for insights.

Sampling Techniques: Select participants based on criteria relevant to your research

- Purposive Sampling: Choose participants with specific characteristics.

- Snowball Sampling: Find new participants through referrals.

- Convenience Sampling: Select participants who are easily accessible.

Interviewing and Observation Techniques

- Develop Guides: Create structured or semi-structured interview guides.

- Active Listening: Focus on both verbal and nonverbal cues.

- Probing Questions: Ask follow-ups to gain deeper insights.

- Field Notes: Record detailed observations and interview notes.

Data Analysis Techniques: Analyze data through

- Transcription: Convert recordings into text.

- Coding: Identify patterns and themes.

- Thematic Analysis: Organize data into categories.

- Narrative Analysis: Explore participants’ stories and experiences.

Writing a Research Report: Communicate your research clearly

- Introduction: State the research problem and objectives.

- Literature Review: Summarize relevant research.

- Methodology: Describe your research design and methods.

- Findings: Present results with detailed descriptions and quotes.

- Discussion: Interpret findings and discuss their implications.

- Conclusion: Summarize key findings and contributions.

- References: List all sources cited.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Check out data analysis and interpretation:-

Thematic Analysis

- Coding: Break data into smaller pieces to find patterns.

- Categorizing: Group codes into broader themes.

- Identifying Patterns: Find recurring themes and subthemes.

Identifying Patterns and Themes

- Compare Data: Look for similarities and differences.

- Create a Thematic Map: Visualize how themes relate.

- Refine Themes: Continuously revise and improve themes.

Writing a Research Report

- Clear Language: Use simple, direct language.

- Rich Descriptions: Include vivid quotes and examples.

- Theoretical Framework: Link findings to existing theories.

- Limitations: Note any study limitations.

- Implications: Discuss the impact on theory and practice.

Data analysis is iterative—be prepared to revisit and refine your findings.

Research Methods for High School Students

Check out the research methods for high school students:-

- Develop Guides: Create a list of structured or semi-structured questions.

- Active Listening: Focus on participants’ responses.

- Probing Questions: Ask follow-ups for deeper understanding.

- Building Rapport: Establish trust with participants.

- Ethics: Get consent, ensure confidentiality, and respect participants.

- Participant Observation: Join the environment to experience it firsthand.

- Non-participant Observation: Watch without joining in.

- Field Notes: Record observations systematically.

- Key Behaviors: Focus on relevant actions.

- Ethics: Respect privacy and avoid disruption.

Focus Groups

- Group Selection: Recruit participants with similar traits.

- Moderator Role: Guide and keep the discussion focused.

- Comfortable Atmosphere: Encourage open sharing.

- Active Listening: Monitor group dynamics and ask clarifying questions.

- Data Analysis: Record and analyze key themes from discussions.

Document Analysi s

- Select Documents: Choose relevant documents for your research.

- Close Reading: Examine content, structure, and language.

- Coding: Identify and categorize key themes.

- Contextualization: Consider the historical and social context.

- Ethics: Follow copyright and privacy laws.

Choose the method that fits your research question and resources. Combining methods can provide a fuller understanding of your topic.

Ethical Considerations in Qualitative Research

Check out the ethical considerations in qualitative research:-

Informed Consent

- Explain Purpose: Clearly state the research aims.

- Detail Procedures: Describe what participants will do.

- Discuss Risks and Benefits: Outline any potential risks and benefits.

- Obtain Consent: Get written or verbal consent, based on literacy levels.

- Withdrawal: Ensure participants know they can leave at any time.

Confidentiality and Anonymity

- Protect Identity: Use pseudonyms or codes.

- Secure Data: Store data safely to prevent unauthorized access.

- Consent for Sharing: Get explicit consent for any data sharing.

- Data Management: Be clear about how data is stored and disposed of.

Respect for Participants

- Dignity and Respect: Treat participants with care.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Be aware of cultural and social differences.

- Avoid Harm: Prevent causing any distress.

- Build Trust: Communicate openly with participants.

Avoiding Harm

- Minimize Risks: Reduce potential risks to participants.

- Provide Support: Offer help if needed.

- Impact Awareness: Consider how findings may affect participants.

- Power Dynamics: Be mindful of power imbalances between researcher and participants.

Following these ethical principles ensures responsible and respectful research.

Writing a Qualitative Research Paper

Check out the best tips for writing a qualitative research paper:-

- Introduction: State your question, background, and outline.

- Literature Review: Summarize related research.

- Methodology: Describe your design, participants, and methods.

- Findings: Present results with quotes and examples.

- Discussion: Interpret findings and discuss implications.

- Conclusion: Summarize key points and suggest future research.

- References: List all sources.

Data Analysis

- Coding: Identify patterns in data.

- Thematic Analysis: Describe main themes.

- Member Checking: Verify findings with participants.

- Reflexivity: Acknowledge your biases.

Citation and Referencing

- Style: Use APA, MLA, or Chicago .

- In-text Citations: Cite sources within the text.

- Reference List: Provide full details of sources.

Presenting Findings

- Vivid Language: Use clear, descriptive language.

- Visual Aids: Add graphs, charts, or images.

- Clear Writing: Avoid jargon.

- Logical Structure: Organize information clearly.

These steps will help you write a clear and effective qualitative research paper.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Check out the common challenges and solutions:-

Researcher Bias

- Reflexivity: Regularly reflect on your own biases.

- Triangulation: Use multiple sources and methods to validate findings.

- Peer Review: Get feedback from colleagues to spot potential biases.

Data Saturation

- Theoretical Saturation: Identify when new data adds little new insight.

- Time Management: Balance data collection and analysis to stay organized.

- Focus on Core Themes: Stick to data related to your research questions.

Time Management

- Prioritize Tasks: Develop a clear research timeline.

- Efficient Data Management: Use tools or software to organize data.

- Seek Support: Collaborate or delegate tasks as needed.

Ethical Considerations

- Informed Consent: Ensure clear and ongoing consent from participants.

- Confidentiality: Protect participant identities and data.

- Harm Minimization: Be aware of and mitigate potential negative impacts.

- Ethical Review: Submit to an ethics board if required.

Using Technology in Qualitative Research

Leveraging technology in qualitative research:-

Data Collection

- Online Surveys: Use open-ended questions to gather qualitative data.

- Social Media Analysis: Study online interactions for insights.

- Video Conferencing: Conduct remote interviews or focus groups.

- Audio and Video Recording: Capture detailed data for later analysis.

Data Management and Analysis

- CAQDAS: Use tools like NVivo, Atlas.ti, or MAXQDA for organizing and analyzing data.

- Transcription Software: Convert recordings into text for easier analysis.

- Cloud Storage: Store and access data securely from anywhere.

Challenges and Considerations

- Digital Divide: Ensure all participants have access to technology.

- Data Privacy and Security: Protect participant information.

- Technical Issues: Prepare for potential technical problems.

- Ethical Implications: Address the ethics of online data collection.

Using technology effectively can improve the efficiency, rigor, and depth of your qualitative research.

Presenting Qualitative Research Findings

Check out the best tips to present qualitative research findings:-

Storytelling with Data

- Narrative Approach: Turn findings into a compelling story.

- Thick Description: Provide detailed context to bring findings to life.

- Vivid Language: Use descriptive language to engage your audience.

- Participant Voices: Include direct quotes to highlight key points.

Visual Aids

- Tables and Figures: Summarize data visually.

- Diagrams and Charts: Show relationships between themes.

- Images and Photographs: Enhance understanding and engagement.

- Participant Anonymity: Use pseudonyms or codes to protect identities.

- Sensitive Information: Handle data with care.

- Research Integrity: Present findings accurately without exaggeration.

Audience Adaptation

- Tailor Presentation: Adjust for audience knowledge and interests.

- Clear Language: Avoid jargon and complex terms.

- Engage Audience: Use interactive elements or questions to stimulate discussion.

Following these strategies will help you effectively convey the insights and significance of your qualitative research.

How to choose a qualitative research topic?

Check out the best tips to choose a qualiative research topic:-

Identify Your Interests

- Personal Passion: Pick a topic that genuinely excites you.

- Academic Alignment: Choose something relevant to your studies.

- Social Relevance: Focus on issues impacting your community or society.

Explore Potential Topics

- Brainstorm: Create a list of possible topics.

- Literature Review: Look at existing research to find gaps.

- Mind Mapping: Visualize connections between ideas.

Narrow Down Your Focus

- Define Your Question: Clearly state what you want to investigate.

- Consider Feasibility: Check if you have access to the necessary data and resources.

- Assess Ethics: Evaluate any potential ethical concerns.

These steps will help you select a meaningful and manageable research topic.

Qualitative research lets high school students explore their world with curiosity. By choosing a topic, using the right methods, and being ethical, you’ll build skills in thinking, communication, and problem-solving. Your discoveries can deepen your understanding of social issues and human behavior.

Start with a question, and dive in. There are so many stories waiting to be uncovered!

Related Posts

149+ Most Interesting Civil Engineering Research Topics For Undergraduates

179+ Top-Rated Quantitative Research Topics For Accounting Students [Updated 2024]

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Qualitative Research for Senior High School Students

2019, SAMSUDIN N. ABDULLAH, PhD

This power-point presentation (pdf) is specially prepared for the teachers who are teaching Practical Research 1 (Qualitative Research) in senior high school curriculum. Practical Research 1 aims to develop the critical thinking and problem solving skills of senior high school students through Qualitative Research. Its goal is to equip them with necessary skills and experience to write their own research paper. The actual research process will let the students experience conducting a research; from conceptualization of the research topic or title until the actual writing of their own research paper. Towards the end of the subject, the students are expected to produce their own research paper in group with four members.

Related Papers

Hernando Jr L Bernal PhD

Teaching Practical Research in the Senior High School was a challenge but at the same time a room for exploration. This study investigated the key areas in the interconnected teaching strategies employed to grade 12 students of which are most and least helpful in coming up with a good research output and what suggestions can be given to improve areas that are least useful. It is qualitative in nature and used phenomenological design. Reflection worksheets and interview schedule were the main sources of data. Results reveal that students come up with a good research output because of the following key areas: 'guidance from someone who is passionate with research' as represented by their research critique, research teacher, resource speaker from the seminar conducted, and group mates; 'guidance from something or activities conducted' like the sample researches in the library visitation, worksheets answered, and the research defenses; and 'teamwork' among the members of the group. On the other hand, key areas which are least useful are: 'clash of ideas and unequal effort' among the members; 'time consuming for some of the written works'; and 'no review of related literature' during the library hopping. Suggestions given where: to choose your own group mates of which each member should have the same field of interest, to remove worksheets not needed in the research paper; and to check online regarding availability of literature in the library. Further suggestions are to rearranged the sequence of the interconnected strategies which are as follows: grouping of students, having a research critique, seminar in conducting research, library visitation/work activity, proposal defense, final defense and the worksheet activities be given throughout the semester. Furthermore, there should be a culminating activity for students to share their outputs. Teaching research is a wholesome process. By then, the researcher recommends to organize a group orientation for the teacher-coaches/mentors on the creation of school research council or school mentoring committee for peer reviewing on the students research output. Further, student research presentation (oral, poster, gallery type, etc.), student research conference/colloquium, student research journal, etc. be organized to further nourish the culture of research in the part of the students, teachers and staffs involve.

Marcella Stark , Julie Combs , John Slate Ph. D.

In this article, we outline a course wherein the instructors teach students how to conduct rigorous qualitative research. We discuss the four major distinct, but overlapping, phases of the course: conceptual/theoretical, technical, applied, and emergent scholar. Students write several qualitative reports, called qualitative notebooks, which involve data that they collect (via three different types of interviews), analyze (using nine qualitative analysis techniques via qualitative software), and interpret. Each notebook is edited by the instructors to help them improve the quality of subsequent notebook reports. Finally, we advocate asking students who have previously taken this course to team-teach future courses. We hope that our exemplar for teaching and learning qualitative research will be useful for teachers and students alike.

Dr. Purnima Trivedi

Mjhae Corinthians

Can tenth graders go beyond writing reports to conduct "authentic" research? English teachers and the school librarian collaborate to gather data in a qualitative action research study that investigates the effectiveness of an assignment that requires primary research methods and an essay of two thousand words. The unit is designed as a performance-based assessment task, including rubrics, student journals, and peer editing. Students develop research questions, write proposals, design questionnaires and interviews, and learn techniques of display and analysis. Concurrently, their teachers gather data from observation, journals, and questionnaires to determine the strengths and weaknesses of the assignment. The research assignment has become analogous to "Take two aspirins and call me in the morning." It doesn't seem to do any harm and may even do some good. Educators adjust the dosage for older students: the length of the paper grows with the time allotted to the task but the prescription is the same. It is universally accepted as a benign activity, as evidenced by the prevalence of standards and objectives for research skills in school curricula. It has become a staple in the educational diet of the high school student. Librarians promote the research assignment because they want students to get better at searching, retrieving, and evaluating information. English teachers see it as an opportunity for sustained writing. Parents like it because it is good preparation for college. Everyone likes it because it gets students into the library and reading. So, what is wrong with research as it is traditionally taught in secondary schools? And what do students think?

Methodological Issues in Management Research: Advances, Challenges, and the Way Ahead

Richa Awasthy

Current paper is an overview of qualitative research. It starts with discussing meaning of research and links it with a framework of experiential learning. Complexity of socio-political environment can be captured with methodologies appropriate to capture dynamism and intricacy of human life. Qualitative research is a process of capturing lived-in experiences of individuals, groups, and society. It is an umbrella concept which involves variety of methods of data collection such as interviews, observations, focused group discussions, projective tools, drawings, narratives, biographies, videos, and anything which helps to understand world of participants. Researcher is an instrument of data collection and plays a crucial role in collecting data. Main steps and key characteristics of qualitative research are covered in this paper. Reader would develop appreciation for methodiness in qualitative research. Quality of qualitative research is explained referring to aspects related to rigor...

Nurse Education Today

Stefanos Mantzoukas

SAMSUDIN N. ABDULLAH, PhD, MOHAMAD T. SIMPAL, MAST & ARJEY B. MANGAKOY

SAMSUDIN N ABDULLAH, PhD

This Self-Instructional Module (SIM) in Practical Research 2 (Quantitative Research) is specially designed for the senior high school students and teachers. The explanation and examples in this SIM are based from the personal experiences of the authors in actual conduct of both basic and action researches. There is a YOUTUBE Channel of the major author (Samsudin Noh Abdullah) for the detailed video lessons anchored on this module.

Psychology Teaching Review

Adam Danquah

This paper describes the development and delivery of an innovative approach to teaching qualitative research methods in psychology. The teaching incorporated a range of ‘active’ pedagogical practices that it shares with other teaching in this area, but was designed in such a way as to follow the arc of a qualitative research project in its entirety over several sessions, whilst episodicallydealing with distinct methodological approaches along the way. In line with this design, and the mutuality of the learning, it was called a ‘qualitative learning series’. Following Mason (2002), the paper also considers the challenge of qualitative teaching in the context of academic psychology, and touches upon whether developments in theyears since have made for much difference. These strands of the paper come together in how the teaching met these challenges.

Language Teaching Research

Hossein Nassaji

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Thomas Dana

Oliver Mason

Quality & Quantity

Mansoor Niaz

UNICAF University - Zambia

Ivan Steenkamp

Barbara Kawulich

Victoria Clarke

Serdar Kaya

Dr. CHINAZO ECHEZONA-JOHNSON

Research on humanities and social sciences

Maxwell Musingafi

Psychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary Journal

Psychology and Education , RUTH VILLARTA

The Qualitative Report

yuliang liu

Rose Barbour

keith grammer

Juliette Galonnier

Carol Mullen

International Journal of Research

Enas Abuhamda , Islam Asim Ismail

Nursing Research

Janice Morse

Qualitative Research in Education

Mahmut Kalman

Bisector Marumo

International Forum Journal

David Osorio

South East Asia Journal of Medical Sciences

Ishwar Bagoji

Ali Kılıçoglu

Ntibaziyaremye Alexis

Review of Applied Management and Social Sciences

hassan raza

SEID A H M E D MUHE

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

100 Interesting Research Paper Topics for High Schoolers

What’s covered:, how to pick the right research topic, elements of a strong research paper.

- Interesting Research Paper Topics

Composing a research paper can be a daunting task for first-time writers. In addition to making sure you’re using concise language and your thoughts are organized clearly, you need to find a topic that draws the reader in.

CollegeVine is here to help you brainstorm creative topics! Below are 100 interesting research paper topics that will help you engage with your project and keep you motivated until you’ve typed the final period.

A research paper is similar to an academic essay but more lengthy and requires more research. This added length and depth is bittersweet: although a research paper is more work, you can create a more nuanced argument, and learn more about your topic. Research papers are a demonstration of your research ability and your ability to formulate a convincing argument. How well you’re able to engage with the sources and make original contributions will determine the strength of your paper.

You can’t have a good research paper without a good research paper topic. “Good” is subjective, and different students will find different topics interesting. What’s important is that you find a topic that makes you want to find out more and make a convincing argument. Maybe you’ll be so interested that you’ll want to take it further and investigate some detail in even greater depth!

For example, last year over 4000 students applied for 500 spots in the Lumiere Research Scholar Program , a rigorous research program founded by Harvard researchers. The program pairs high-school students with Ph.D. mentors to work 1-on-1 on an independent research project . The program actually does not require you to have a research topic in mind when you apply, but pro tip: the more specific you can be the more likely you are to get in!

Introduction

The introduction to a research paper serves two critical functions: it conveys the topic of the paper and illustrates how you will address it. A strong introduction will also pique the interest of the reader and make them excited to read more. Selecting a research paper topic that is meaningful, interesting, and fascinates you is an excellent first step toward creating an engaging paper that people will want to read.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is technically part of the introduction—generally the last sentence of it—but is so important that it merits a section of its own. The thesis statement is a declarative sentence that tells the reader what the paper is about. A strong thesis statement serves three purposes: present the topic of the paper, deliver a clear opinion on the topic, and summarize the points the paper will cover.

An example of a good thesis statement of diversity in the workforce is:

Diversity in the workplace is not just a moral imperative but also a strategic advantage for businesses, as it fosters innovation, enhances creativity, improves decision-making, and enables companies to better understand and connect with a diverse customer base.

The body is the largest section of a research paper. It’s here where you support your thesis, present your facts and research, and persuade the reader.

Each paragraph in the body of a research paper should have its own idea. The idea is presented, generally in the first sentence of the paragraph, by a topic sentence. The topic sentence acts similarly to the thesis statement, only on a smaller scale, and every sentence in the paragraph with it supports the idea it conveys.

An example of a topic sentence on how diversity in the workplace fosters innovation is:

Diversity in the workplace fosters innovation by bringing together individuals with different backgrounds, perspectives, and experiences, which stimulates creativity, encourages new ideas, and leads to the development of innovative solutions to complex problems.

The body of an engaging research paper flows smoothly from one idea to the next. Create an outline before writing and order your ideas so that each idea logically leads to another.

The conclusion of a research paper should summarize your thesis and reinforce your argument. It’s common to restate the thesis in the conclusion of a research paper.

For example, a conclusion for a paper about diversity in the workforce is:

In conclusion, diversity in the workplace is vital to success in the modern business world. By embracing diversity, companies can tap into the full potential of their workforce, promote creativity and innovation, and better connect with a diverse customer base, ultimately leading to greater success and a more prosperous future for all.

Reference Page

The reference page is normally found at the end of a research paper. It provides proof that you did research using credible sources, properly credits the originators of information, and prevents plagiarism.

There are a number of different formats of reference pages, including APA, MLA, and Chicago. Make sure to format your reference page in your teacher’s preferred style.

- Analyze the benefits of diversity in education.

- Are charter schools useful for the national education system?

- How has modern technology changed teaching?

- Discuss the pros and cons of standardized testing.

- What are the benefits of a gap year between high school and college?

- What funding allocations give the most benefit to students?

- Does homeschooling set students up for success?

- Should universities/high schools require students to be vaccinated?

- What effect does rising college tuition have on high schoolers?

- Do students perform better in same-sex schools?

- Discuss and analyze the impacts of a famous musician on pop music.

- How has pop music evolved over the past decade?

- How has the portrayal of women in music changed in the media over the past decade?

- How does a synthesizer work?

- How has music evolved to feature different instruments/voices?

- How has sound effect technology changed the music industry?

- Analyze the benefits of music education in high schools.

- Are rehabilitation centers more effective than prisons?

- Are congestion taxes useful?

- Does affirmative action help minorities?

- Can a capitalist system effectively reduce inequality?

- Is a three-branch government system effective?

- What causes polarization in today’s politics?

- Is the U.S. government racially unbiased?

- Choose a historical invention and discuss its impact on society today.

- Choose a famous historical leader who lost power—what led to their eventual downfall?

- How has your country evolved over the past century?

- What historical event has had the largest effect on the U.S.?

- Has the government’s response to national disasters improved or declined throughout history?

- Discuss the history of the American occupation of Iraq.

- Explain the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict.

- Is literature relevant in modern society?

- Discuss how fiction can be used for propaganda.

- How does literature teach and inform about society?

- Explain the influence of children’s literature on adulthood.

- How has literature addressed homosexuality?

- Does the media portray minorities realistically?

- Does the media reinforce stereotypes?

- Why have podcasts become so popular?

- Will streaming end traditional television?

- What is a patriot?

- What are the pros and cons of global citizenship?

- What are the causes and effects of bullying?

- Why has the divorce rate in the U.S. been declining in recent years?

- Is it more important to follow social norms or religion?

- What are the responsible limits on abortion, if any?

- How does an MRI machine work?

- Would the U.S. benefit from socialized healthcare?

- Elderly populations

- The education system

- State tax bases

- How do anti-vaxxers affect the health of the country?

- Analyze the costs and benefits of diet culture.

- Should companies allow employees to exercise on company time?

- What is an adequate amount of exercise for an adult per week/per month/per day?

- Discuss the effects of the obesity epidemic on American society.

- Are students smarter since the advent of the internet?

- What departures has the internet made from its original design?

- Has digital downloading helped the music industry?

- Discuss the benefits and costs of stricter internet censorship.

- Analyze the effects of the internet on the paper news industry.

- What would happen if the internet went out?

- How will artificial intelligence (AI) change our lives?

- What are the pros and cons of cryptocurrency?

- How has social media affected the way people relate with each other?

- Should social media have an age restriction?

- Discuss the importance of source software.

- What is more relevant in today’s world: mobile apps or websites?

- How will fully autonomous vehicles change our lives?

- How is text messaging affecting teen literacy?

Mental Health

- What are the benefits of daily exercise?

- How has social media affected people’s mental health?

- What things contribute to poor mental and physical health?

- Analyze how mental health is talked about in pop culture.

- Discuss the pros and cons of more counselors in high schools.

- How does stress affect the body?

- How do emotional support animals help people?

- What are black holes?

- Discuss the biggest successes and failures of the EPA.

- How has the Flint water crisis affected life in Michigan?

- Can science help save endangered species?

- Is the development of an anti-cancer vaccine possible?

Environment

- What are the effects of deforestation on climate change?

- Is climate change reversible?

- How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect global warming and climate change?

- Are carbon credits effective for offsetting emissions or just marketing?

- Is nuclear power a safe alternative to fossil fuels?

- Are hybrid vehicles helping to control pollution in the atmosphere?

- How is plastic waste harming the environment?

- Is entrepreneurism a trait people are born with or something they learn?

- How much more should CEOs make than their average employee?

- Can you start a business without money?

- Should the U.S. raise the minimum wage?

- Discuss how happy employees benefit businesses.

- How important is branding for a business?

- Discuss the ease, or difficulty, of landing a job today.

- What is the economic impact of sporting events?

- Are professional athletes overpaid?

- Should male and female athletes receive equal pay?

- What is a fair and equitable way for transgender athletes to compete in high school sports?

- What are the benefits of playing team sports?

- What is the most corrupt professional sport?

Where to Get More Research Paper Topic Ideas

If you need more help brainstorming topics, especially those that are personalized to your interests, you can use CollegeVine’s free AI tutor, Ivy . Ivy can help you come up with original research topic ideas, and she can also help with the rest of your homework, from math to languages.

Disclaimer: This post includes content sponsored by Lumiere Education.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 December 2020

Enhancing senior high school student engagement and academic performance using an inclusive and scalable inquiry-based program

- Locke Davenport Huyer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1526-7122 1 , 2 na1 ,

- Neal I. Callaghan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8214-3395 1 , 3 na1 ,

- Sara Dicks 4 ,

- Edward Scherer 4 ,

- Andrey I. Shukalyuk 1 ,

- Margaret Jou 4 &

- Dawn M. Kilkenny ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3899-9767 1 , 5

npj Science of Learning volume 5 , Article number: 17 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

7 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

The multi-disciplinary nature of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) careers often renders difficulty for high school students navigating from classroom knowledge to post-secondary pursuits. Discrepancies between the knowledge-based high school learning approach and the experiential approach of future studies leaves some students disillusioned by STEM. We present Discovery , a term-long inquiry-focused learning model delivered by STEM graduate students in collaboration with high school teachers, in the context of biomedical engineering. Entire classes of high school STEM students representing diverse cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds engaged in iterative, problem-based learning designed to emphasize critical thinking concomitantly within the secondary school and university environments. Assessment of grades and survey data suggested positive impact of this learning model on students’ STEM interests and engagement, notably in under-performing cohorts, as well as repeating cohorts that engage in the program on more than one occasion. Discovery presents a scalable platform that stimulates persistence in STEM learning, providing valuable learning opportunities and capturing cohorts of students that might otherwise be under-engaged in STEM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Subject integration and theme evolution of STEM education in K-12 and higher education research

Skill levels and gains in university STEM education in China, India, Russia and the United States

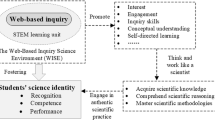

Exploring the impact of web-based inquiry on elementary school students’ science identity development in a STEM learning unit

Introduction.

High school students with diverse STEM interests often struggle to understand the STEM experience outside the classroom 1 . The multi-disciplinary nature of many career fields can foster a challenge for students in their decision to enroll in appropriate high school courses while maintaining persistence in study, particularly when these courses are not mandatory 2 . Furthermore, this challenge is amplified by the known discrepancy between the knowledge-based learning approach common in high schools and the experiential, mastery-based approaches afforded by the subsequent undergraduate model 3 . In the latter, focused classes, interdisciplinary concepts, and laboratory experiences allow for the application of accumulated knowledge, practice in problem solving, and development of both general and technical skills 4 . Such immersive cooperative learning environments are difficult to establish in the secondary school setting and high school teachers often struggle to implement within their classroom 5 . As such, high school students may become disillusioned before graduation and never experience an enriched learning environment, despite their inherent interests in STEM 6 .

It cannot be argued that early introduction to varied math and science disciplines throughout high school is vital if students are to pursue STEM fields, especially within engineering 7 . However, the majority of literature focused on student interest and retention in STEM highlights outcomes in US high school learning environments, where the sciences are often subject-specific from the onset of enrollment 8 . In contrast, students in the Ontario (Canada) high school system are required to complete Level 1 and 2 core courses in science and math during Grades 9 and 10; these courses are offered as ‘applied’ or ‘academic’ versions and present broad topics of content 9 . It is not until Levels 3 and 4 (generally Grades 11 and 12, respectively) that STEM classes become subject-specific (i.e., Biology, Chemistry, and/or Physics) and are offered as “university”, “college”, or “mixed” versions, designed to best prepare students for their desired post-secondary pursuits 9 . Given that Levels 3 and 4 science courses are not mandatory for graduation, enrollment identifies an innate student interest in continued learning. Furthermore, engagement in these post-secondary preparatory courses is also dependent upon achieving successful grades in preceding courses, but as curriculum becomes more subject-specific, students often yield lower degrees of success in achieving course credit 2 . Therefore, it is imperative that learning supports are best focused on ensuring that those students with an innate interest are able to achieve success in learning.

When given opportunity and focused support, high school students are capable of successfully completing rigorous programs at STEM-focused schools 10 . Specialized STEM schools have existed in the US for over 100 years; generally, students are admitted after their sophomore year of high school experience (equivalent to Grade 10) based on standardized test scores, essays, portfolios, references, and/or interviews 11 . Common elements to this learning framework include a diverse array of advanced STEM courses, paired with opportunities to engage in and disseminate cutting-edge research 12 . Therein, said research experience is inherently based in the processes of critical thinking, problem solving, and collaboration. This learning framework supports translation of core curricular concepts to practice and is fundamental in allowing students to develop better understanding and appreciation of STEM career fields.

Despite the described positive attributes, many students do not have the ability or resources to engage within STEM-focused schools, particularly given that they are not prevalent across Canada, and other countries across the world. Consequently, many public institutions support the idea that post-secondary led engineering education programs are effective ways to expose high school students to engineering education and relevant career options, and also increase engineering awareness 13 . Although singular class field trips are used extensively to accomplish such programs, these may not allow immersive experiences for application of knowledge and practice of skills that are proven to impact long-term learning and influence career choices 14 , 15 . Longer-term immersive research experiences, such as after-school programs or summer camps, have shown successful at recruiting students into STEM degree programs and careers, where longevity of experience helps foster self-determination and interest-led, inquiry-based projects 4 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 .

Such activities convey the elements that are suggested to make a post-secondary led high school education programs successful: hands-on experience, self-motivated learning, real-life application, immediate feedback, and problem-based projects 20 , 21 . In combination with immersion in university teaching facilities, learning is authentic and relevant, similar to the STEM school-focused framework, and consequently representative of an experience found in actual STEM practice 22 . These outcomes may further be a consequence of student engagement and attitude: Brown et al. studied the relationships between STEM curriculum and student attitudes, and found the latter played a more important role in intention to persist in STEM when compared to self-efficacy 23 . This is interesting given that student self-efficacy has been identified to influence ‘motivation, persistence, and determination’ in overcoming challenges in a career pathway 24 . Taken together, this suggests that creation and delivery of modern, exciting curriculum that supports positive student attitudes is fundamental to engage and retain students in STEM programs.

Supported by the outcomes of identified effective learning strategies, University of Toronto (U of T) graduate trainees created a novel high school education program Discovery , to develop a comfortable yet stimulating environment of inquiry-focused iterative learning for senior high school students (Grades 11 & 12; Levels 3 & 4) at non-specialized schools. Built in strong collaboration with science teachers from George Harvey Collegiate Institute (Toronto District School Board), Discovery stimulates application of STEM concepts within a unique term-long applied curriculum delivered iteratively within both U of T undergraduate teaching facilities and collaborating high school classrooms 25 . Based on the volume of medically-themed news and entertainment that is communicated to the population at large, the rapidly-growing and diverse field of biomedical engineering (BME) were considered an ideal program context 26 . In its definition, BME necessitates cross-disciplinary STEM knowledge focused on the betterment of human health, wherein Discovery facilitates broadening student perspective through engaging inquiry-based projects. Importantly, Discovery allows all students within a class cohort to work together with their classroom teacher, stimulating continued development of a relevant learning community that is deemed essential for meaningful context and important for transforming student perspectives and understandings 27 , 28 . Multiple studies support the concept that relevant learning communities improve student attitudes towards learning, significantly increasing student motivation in STEM courses, and consequently improving the overall learning experience 29 . Learning communities, such as that provided by Discovery , also promote the formation of self-supporting groups, greater active involvement in class, and higher persistence rates for participating students 30 .

The objective of Discovery , through structure and dissemination, is to engage senior high school science students in challenging, inquiry-based practical BME activities as a mechanism to stimulate comprehension of STEM curriculum application to real-world concepts. Consequent focus is placed on critical thinking skill development through an atmosphere of perseverance in ambiguity, something not common in a secondary school knowledge-focused delivery but highly relevant in post-secondary STEM education strategies. Herein, we describe the observed impact of the differential project-based learning environment of Discovery on student performance and engagement. We identify the value of an inquiry-focused learning model that is tangible for students who struggle in a knowledge-focused delivery structure, where engagement in conceptual critical thinking in the relevant subject area stimulates student interest, attitudes, and resulting academic performance. Assessment of study outcomes suggests that when provided with a differential learning opportunity, student performance and interest in STEM increased. Consequently, Discovery provides an effective teaching and learning framework within a non-specialized school that motivates students, provides opportunity for critical thinking and problem-solving practice, and better prepares them for persistence in future STEM programs.

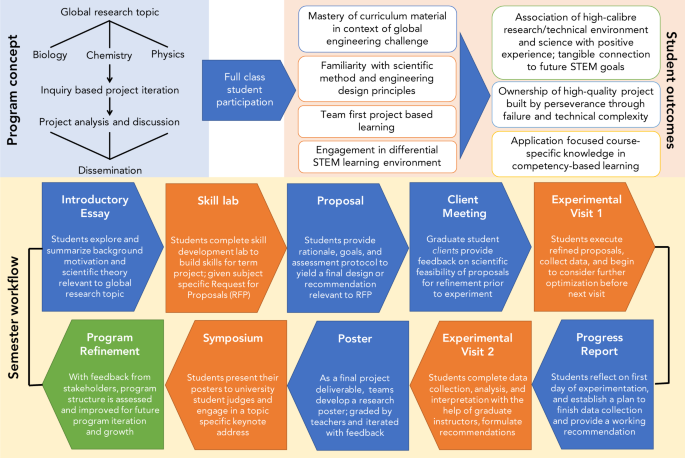

Program delivery

The outcomes of the current study result from execution of Discovery over five independent academic terms as a collaboration between Institute of Biomedical Engineering (graduate students, faculty, and support staff) and George Harvey Collegiate Institute (science teachers and administration) stakeholders. Each term, the program allowed senior secondary STEM students (Grades 11 and 12) opportunity to engage in a novel project-based learning environment. The program structure uses the problem-based engineering capstone framework as a tool of inquiry-focused learning objectives, motivated by a central BME global research topic, with research questions that are inter-related but specific to the curriculum of each STEM course subject (Fig. 1 ). Over each 12-week term, students worked in teams (3–4 students) within their class cohorts to execute projects with the guidance of U of T trainees ( Discovery instructors) and their own high school teacher(s). Student experimental work was conducted in U of T teaching facilities relevant to the research study of interest (i.e., Biology and Chemistry-based projects executed within Undergraduate Teaching Laboratories; Physics projects executed within Undergraduate Design Studios). Students were introduced to relevant techniques and safety procedures in advance of iterative experimentation. Importantly, this experience served as a course term project for students, who were assessed at several points throughout the program for performance in an inquiry-focused environment as well as within the regular classroom (Fig. 1 ). To instill the atmosphere of STEM, student teams delivered their outcomes in research poster format at a final symposium, sharing their results and recommendations with other post-secondary students, faculty, and community in an open environment.

The general program concept (blue background; top left ) highlights a global research topic examined through student dissemination of subject-specific research questions, yielding multifaceted student outcomes (orange background; top right ). Each program term (term workflow, yellow background; bottom panel ), students work on program deliverables in class (blue), iterate experimental outcomes within university facilities (orange), and are assessed accordingly at numerous deliverables in an inquiry-focused learning model.

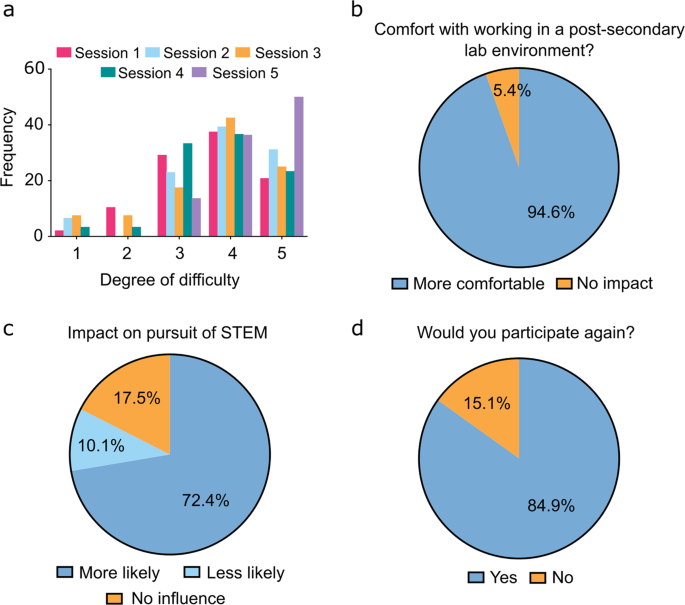

Over the course of five terms there were 268 instances of tracked student participation, representing 170 individual students. Specifically, 94 students participated during only one term of programming, 57 students participated in two terms, 16 students participated in three terms, and 3 students participated in four terms. Multiple instances of participation represent students that enrol in more than one STEM class during their senior years of high school, or who participated in Grade 11 and subsequently Grade 12. Students were surveyed before and after each term to assess program effects on STEM interest and engagement. All grade-based assessments were performed by high school teachers for their respective STEM class cohorts using consistent grading rubrics and assignment structure. Here, we discuss the outcomes of student involvement in this experiential curriculum model.

Student performance and engagement

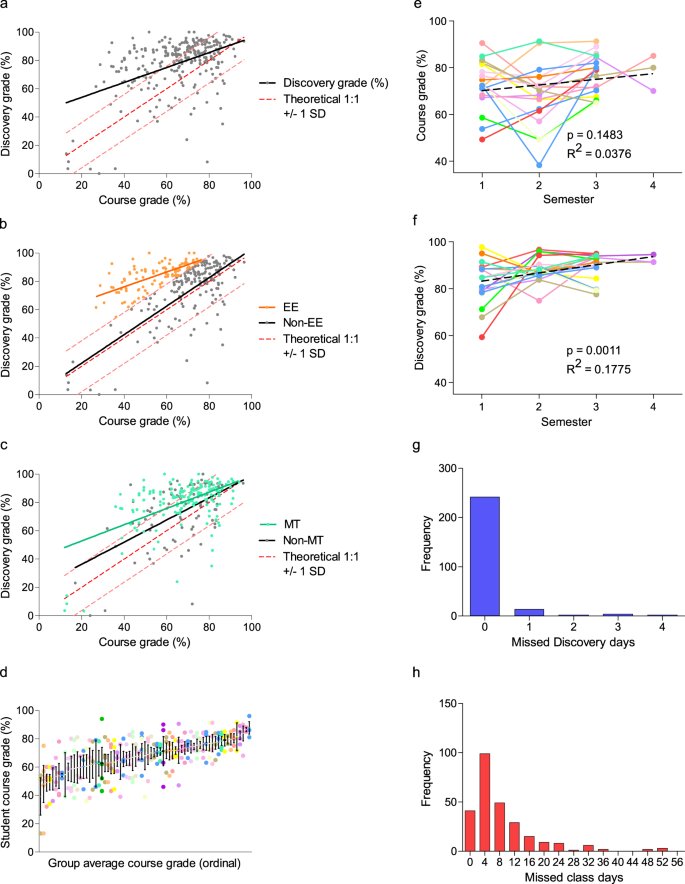

Student grades were assigned, collected, and anonymized by teachers for each Discovery deliverable (background essay, client meeting, proposal, progress report, poster, and final presentation). Teachers anonymized collective Discovery grades, the component deliverable grades thereof, final course grades, attendance in class and during programming, as well as incomplete classroom assignments, for comparative study purposes. Students performed significantly higher in their cumulative Discovery grade than in their cumulative classroom grade (final course grade less the Discovery contribution; p < 0.0001). Nevertheless, there was a highly significant correlation ( p < 0.0001) observed between the grade representing combined Discovery deliverables and the final course grade (Fig. 2a ). Further examination of the full dataset revealed two student cohorts of interest: the “Exceeds Expectations” (EE) subset (defined as those students who achieved ≥1 SD [18.0%] grade differential in Discovery over their final course grade; N = 99 instances), and the “Multiple Term” (MT) subset (defined as those students who participated in Discovery more than once; 76 individual students that collectively accounted for 174 single terms of assessment out of the 268 total student-terms delivered) (Fig. 2b, c ). These subsets were not unrelated; 46 individual students who had multiple experiences (60.5% of total MTs) exhibited at least one occasion in achieving a ≥18.0% grade differential. As students participated in group work, there was concern that lower-performing students might negatively influence the Discovery grade of higher-performing students (or vice versa). However, students were observed to self-organize into groups where all individuals received similar final overall course grades (Fig. 2d ), thereby alleviating these concerns.

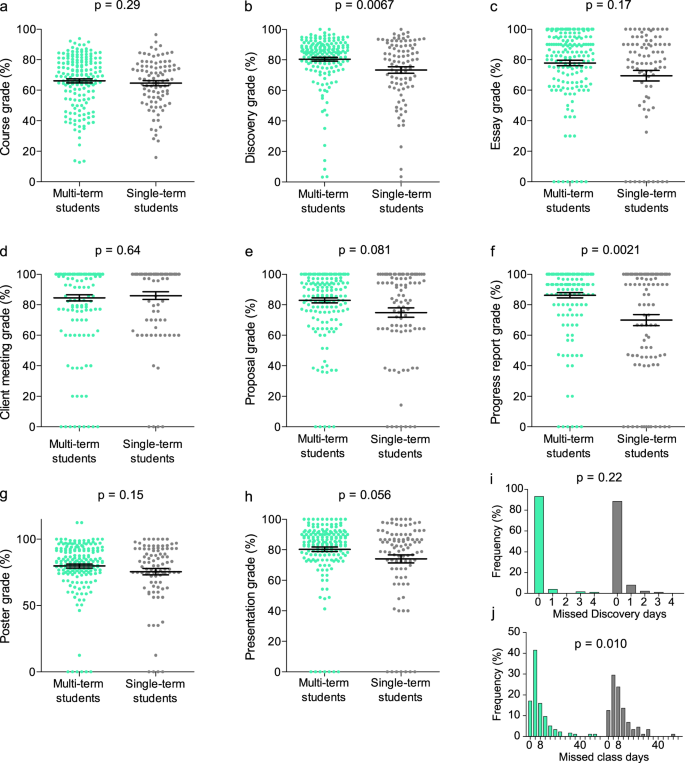

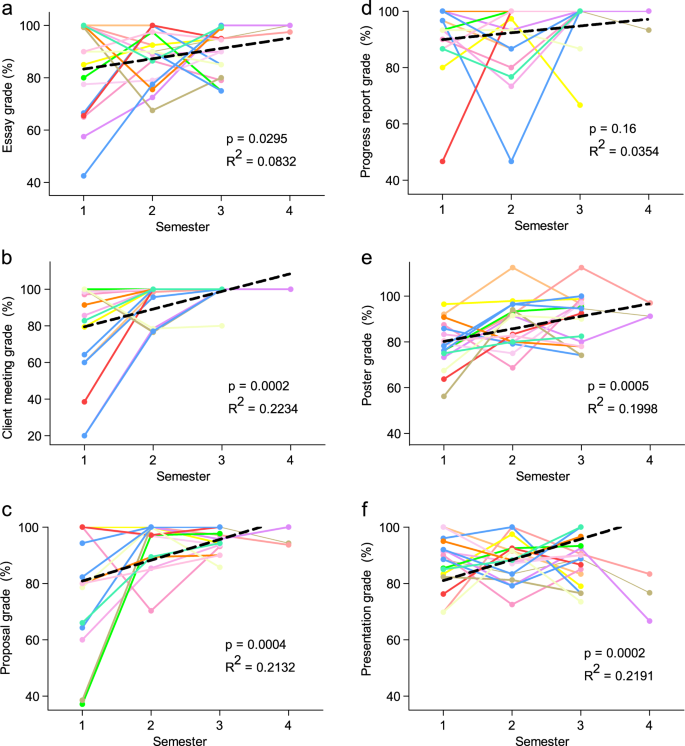

a Linear regression of student grades reveals a significant correlation ( p = 0.0009) between Discovery performance and final course grade less the Discovery contribution to grade, as assessed by teachers. The dashed red line and intervals represent the theoretical 1:1 correlation between Discovery and course grades and standard deviation of the Discovery -course grade differential, respectively. b , c Identification of subgroups of interest, Exceeds Expectations (EE; N = 99, orange ) who were ≥+1 SD in Discovery -course grade differential and Multi-Term (MT; N = 174, teal ), of which N = 65 students were present in both subgroups. d Students tended to self-assemble in working groups according to their final course performance; data presented as mean ± SEM. e For MT students participating at least 3 terms in Discovery , there was no significant correlation between course grade and time, while ( f ) there was a significant correlation between Discovery grade and cumulative terms in the program. Histograms of total absences per student in ( g ) Discovery and ( h ) class (binned by 4 days to be equivalent in time to a single Discovery absence).

The benefits experienced by MT students seemed progressive; MT students that participated in 3 or 4 terms ( N = 16 and 3, respectively ) showed no significant increase by linear regression in their course grade over time ( p = 0.15, Fig. 2e ), but did show a significant increase in their Discovery grades ( p = 0.0011, Fig. 2f ). Finally, students demonstrated excellent Discovery attendance; at least 91% of participants attended all Discovery sessions in a given term (Fig. 2g ). In contrast, class attendance rates reveal a much wider distribution where 60.8% (163 out of 268 students) missed more than 4 classes (equivalent in learning time to one Discovery session) and 14.6% (39 out of 268 students) missed 16 or more classes (equivalent in learning time to an entire program of Discovery ) in a term (Fig. 2h ).

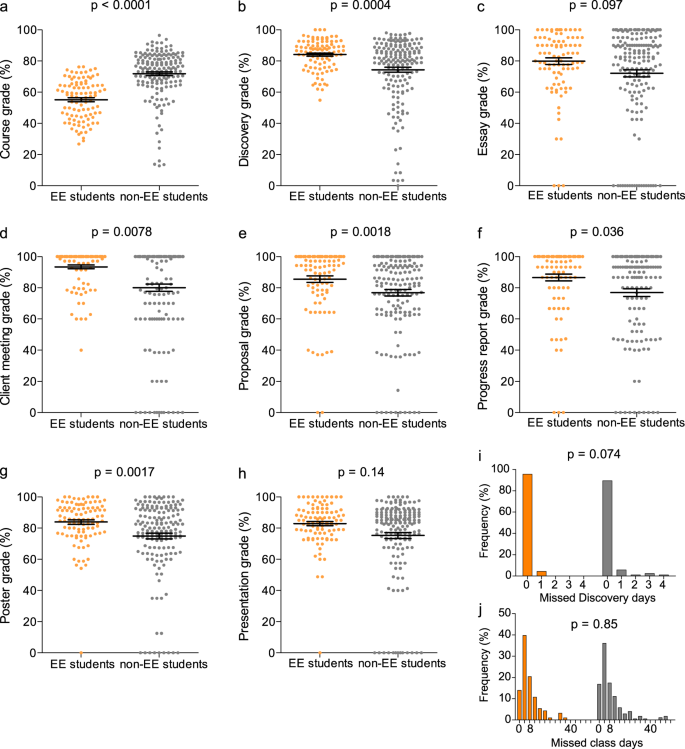

Discovery EE students (Fig. 3 ), roughly by definition, obtained lower course grades ( p < 0.0001, Fig. 3a ) and higher final Discovery grades ( p = 0.0004, Fig. 3b ) than non-EE students. This cohort of students exhibited program grades higher than classmates (Fig. 3c–h ); these differences were significant in every category with the exception of essays, where they outperformed to a significantly lesser degree ( p = 0.097; Fig. 3c ). There was no statistically significant difference in EE vs. non-EE student classroom attendance ( p = 0.85; Fig. 3i, j ). There were only four single day absences in Discovery within the EE subset; however, this difference was not statistically significant ( p = 0.074).

The “Exceeds Expectations” (EE) subset of students (defined as those who received a combined Discovery grade ≥1 SD (18.0%) higher than their final course grade) performed ( a ) lower on their final course grade and ( b ) higher in the Discovery program as a whole when compared to their classmates. d – h EE students received significantly higher grades on each Discovery deliverable than their classmates, except for their ( c ) introductory essays and ( h ) final presentations. The EE subset also tended ( i ) to have a higher relative rate of attendance during Discovery sessions but no difference in ( j ) classroom attendance. N = 99 EE students and 169 non-EE students (268 total). Grade data expressed as mean ± SEM.