Directional Hypothesis: Definition and 10 Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

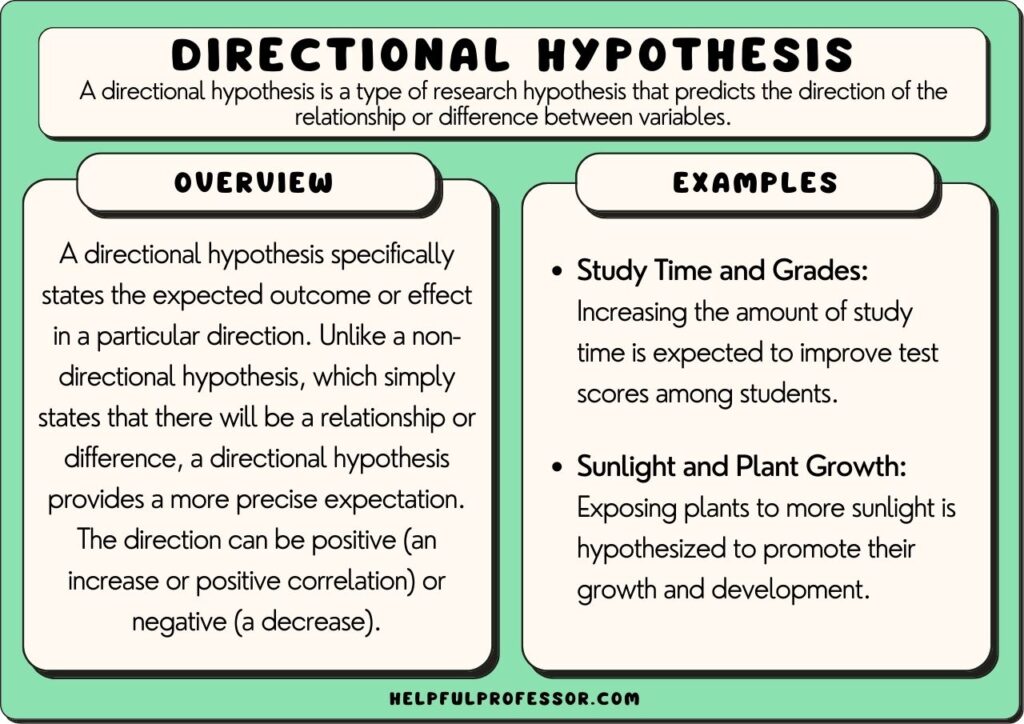

A directional hypothesis refers to a type of hypothesis used in statistical testing that predicts a particular direction of the expected relationship between two variables.

In simpler terms, a directional hypothesis is an educated, specific guess about the direction of an outcome—whether an increase, decrease, or a proclaimed difference in variable sets.

For example, in a study investigating the effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance, a directional hypothesis might state that as sleep deprivation (Independent Variable) increases, cognitive performance (Dependent Variable) decreases (Killgore, 2010). Such a hypothesis offers a clear, directional relationship whereby a specific increase or decrease is anticipated.

Global warming provides another notable example of a directional hypothesis. A researcher might hypothesize that as carbon dioxide (CO2) levels increase, global temperatures also increase (Thompson, 2010). In this instance, the hypothesis clearly articulates an upward trend for both variables.

In any given circumstance, it’s imperative that a directional hypothesis is grounded on solid evidence. For instance, the CO2 and global temperature relationship is based on substantial scientific evidence, and not on a random guess or mere speculation (Florides & Christodoulides, 2009).

Directional vs Non-Directional vs Null Hypotheses

A directional hypothesis is generally contrasted to a non-directional hypothesis. Here’s how they compare:

- Directional hypothesis: A directional hypothesis provides a perspective of the expected relationship between variables, predicting the direction of that relationship (either positive, negative, or a specific difference).

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis denotes the possibility of a relationship between two variables ( the independent and dependent variables ), although this hypothesis does not venture a prediction as to the direction of this relationship (Ali & Bhaskar, 2016). For example, a non-directional hypothesis might state that there exists a relationship between a person’s diet (independent variable) and their mood (dependent variable), without indicating whether improvement in diet enhances mood positively or negatively. Overall, the choice between a directional or non-directional hypothesis depends on the known or anticipated link between the variables under consideration in research studies.

Another very important type of hypothesis that we need to know about is a null hypothesis :

- Null hypothesis : The null hypothesis stands as a universality—the hypothesis that there is no observed effect in the population under study, meaning there is no association between variables (or that the differences are down to chance). For instance, a null hypothesis could be constructed around the idea that changing diet (independent variable) has no discernible effect on a person’s mood (dependent variable) (Yan & Su, 2016). This proposition is the one that we aim to disprove in an experiment.

While directional and non-directional hypotheses involve some integrated expectations about the outcomes (either distinct direction or a vague relationship), a null hypothesis operates on the premise of negating such relationships or effects.

The null hypotheses is typically proposed to be negated or disproved by statistical tests, paving way for the acceptance of an alternate hypothesis (either directional or non-directional).

Directional Hypothesis Examples

1. exercise and heart health.

Research suggests that as regular physical exercise (independent variable) increases, the risk of heart disease (dependent variable) decreases (Jakicic, Davis, Rogers, King, Marcus, Helsel, Rickman, Wahed, Belle, 2016). In this example, a directional hypothesis anticipates that the more individuals maintain routine workouts, the lesser would be their odds of developing heart-related disorders. This assumption is based on the underlying fact that routine exercise can help reduce harmful cholesterol levels, regulate blood pressure, and bring about overall health benefits. Thus, a direction – a decrease in heart disease – is expected in relation with an increase in exercise.

2. Screen Time and Sleep Quality

Another classic instance of a directional hypothesis can be seen in the relationship between the independent variable, screen time (especially before bed), and the dependent variable, sleep quality. This hypothesis predicts that as screen time before bed increases, sleep quality decreases (Chang, Aeschbach, Duffy, Czeisler, 2015). The reasoning behind this hypothesis is the disruptive effect of artificial light (especially blue light from screens) on melatonin production, a hormone needed to regulate sleep. As individuals spend more time exposed to screens before bed, it is predictably hypothesized that their sleep quality worsens.

3. Job Satisfaction and Employee Turnover

A typical scenario in organizational behavior research posits that as job satisfaction (independent variable) increases, the rate of employee turnover (dependent variable) decreases (Cheng, Jiang, & Riley, 2017). This directional hypothesis emphasizes that an increased level of job satisfaction would lead to a reduced rate of employees leaving the company. The theoretical basis for this hypothesis is that satisfied employees often tend to be more committed to the organization and are less likely to seek employment elsewhere, thus reducing turnover rates.

4. Healthy Eating and Body Weight

Healthy eating, as the independent variable, is commonly thought to influence body weight, the dependent variable, in a positive way. For example, the hypothesis might state that as consumption of healthy foods increases, an individual’s body weight decreases (Framson, Kristal, Schenk, Littman, Zeliadt, & Benitez, 2009). This projection is based on the premise that healthier foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are generally lower in calories than junk food, assisting in weight management.

5. Sun Exposure and Skin Health

The association between sun exposure (independent variable) and skin health (dependent variable) allows for a definitive hypothesis declaring that as sun exposure increases, the risk of skin damage or skin cancer increases (Whiteman, Whiteman, & Green, 2001). The premise aligns with the understanding that overexposure to the sun’s ultraviolet rays can deteriorate skin health, leading to conditions like sunburn or, in extreme cases, skin cancer.

6. Study Hours and Academic Performance

A regularly assessed relationship in academia suggests that as the number of study hours (independent variable) rises, so too does academic performance (dependent variable) (Nonis, Hudson, Logan, Ford, 2013). The hypothesis proposes a positive correlation , with an increase in study time expected to contribute to enhanced academic outcomes.

7. Screen Time and Eye Strain

It’s commonly hypothesized that as screen time (independent variable) increases, the likelihood of experiencing eye strain (dependent variable) also increases (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018). This is based on the idea that prolonged engagement with digital screens—computers, tablets, or mobile phones—can cause discomfort or fatigue in the eyes, attributing to symptoms of eye strain.

8. Physical Activity and Stress Levels

In the sphere of mental health, it’s often proposed that as physical activity (independent variable) increases, levels of stress (dependent variable) decrease (Stonerock, Hoffman, Smith, Blumenthal, 2015). Regular exercise is known to stimulate the production of endorphins, the body’s natural mood elevators, helping to alleviate stress.

9. Water Consumption and Kidney Health

A common health-related hypothesis might predict that as water consumption (independent variable) increases, the risk of kidney stones (dependent variable) decreases (Curhan, Willett, Knight, & Stampfer, 2004). Here, an increase in water intake is inferred to reduce the risk of kidney stones by diluting the substances that lead to stone formation.

10. Traffic Noise and Sleep Quality

In urban planning research, it’s often supposed that as traffic noise (independent variable) increases, sleep quality (dependent variable) decreases (Muzet, 2007). Increased noise levels, particularly during the night, can result in sleep disruptions, thus, leading to poor sleep quality.

11. Sugar Consumption and Dental Health

In the field of dental health, an example might be stating as one’s sugar consumption (independent variable) increases, dental health (dependent variable) decreases (Sheiham, & James, 2014). This stems from the fact that sugar is a major factor in tooth decay, and increased consumption of sugary foods or drinks leads to a decline in dental health due to the high likelihood of cavities.

See 15 More Examples of Hypotheses Here

A directional hypothesis plays a critical role in research, paving the way for specific predicted outcomes based on the relationship between two variables. These hypotheses clearly illuminate the expected direction—the increase or decrease—of an effect. From predicting the impacts of healthy eating on body weight to forecasting the influence of screen time on sleep quality, directional hypotheses allow for targeted and strategic examination of phenomena. In essence, directional hypotheses provide the crucial path for inquiry, shaping the trajectory of research studies and ultimately aiding in the generation of insightful, relevant findings.

Ali, S., & Bhaskar, S. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662-669. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F0019-5049.190623

Chang, A. M., Aeschbach, D., Duffy, J. F., & Czeisler, C. A. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep, circadian timing, and next-morning alertness. Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (4), 1232-1237. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1418490112

Cheng, G. H. L., Jiang, D., & Riley, J. H. (2017). Organizational commitment and intrinsic motivation of regular and contractual primary school teachers in China. New Psychology, 19 (3), 316-326. Doi: https://doi.org/10.4103%2F2249-4863.184631

Curhan, G. C., Willett, W. C., Knight, E. L., & Stampfer, M. J. (2004). Dietary factors and the risk of incident kidney stones in younger women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Archives of Internal Medicine, 164 (8), 885–891.

Florides, G. A., & Christodoulides, P. (2009). Global warming and carbon dioxide through sciences. Environment international , 35 (2), 390-401. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2008.07.007

Framson, C., Kristal, A. R., Schenk, J. M., Littman, A. J., Zeliadt, S., & Benitez, D. (2009). Development and validation of the mindful eating questionnaire. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 109 (8), 1439-1444. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2009.05.006

Jakicic, J. M., Davis, K. K., Rogers, R. J., King, W. C., Marcus, M. D., Helsel, D., … & Belle, S. H. (2016). Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: The IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 316 (11), 1161-1171.

Khan, S., & Iqbal, N. (2013). Study of the relationship between study habits and academic achievement of students: A case of SPSS model. Higher Education Studies, 3 (1), 14-26.

Killgore, W. D. (2010). Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. Progress in brain research , 185 , 105-129. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5

Marczinski, C. A., & Fillmore, M. T. (2014). Dissociative antagonistic effects of caffeine on alcohol-induced impairment of behavioral control. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 22 (4), 298–311. doi: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1064-1297.11.3.228

Muzet, A. (2007). Environmental Noise, Sleep and Health. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 11 (2), 135-142. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2006.09.001

Nonis, S. A., Hudson, G. I., Logan, L. B., & Ford, C. W. (2013). Influence of perceived control over time on college students’ stress and stress-related outcomes. Research in Higher Education, 54 (5), 536-552. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018753706925

Sheiham, A., & James, W. P. (2014). A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public health nutrition, 17 (10), 2176-2184. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001400113X

Sheppard, A. L., & Wolffsohn, J. S. (2018). Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. BMJ open ophthalmology , 3 (1), e000146. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2018-000146

Stonerock, G. L., Hoffman, B. M., Smith, P. J., & Blumenthal, J. A. (2015). Exercise as Treatment for Anxiety: Systematic Review and Analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 49 (4), 542–556. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-014-9685-9

Thompson, L. G. (2010). Climate change: The evidence and our options. The Behavior Analyst , 33 , 153-170. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03392211

Whiteman, D. C., Whiteman, C. A., & Green, A. C. (2001). Childhood sun exposure as a risk factor for melanoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic studies. Cancer Causes & Control, 12 (1), 69-82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008980919928

Yan, X., & Su, X. (2009). Linear regression analysis: theory and computing . New Jersey: World Scientific.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions & Examples

Null & Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions, Templates & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shaun Turney . Revised on June 22, 2023.

The null and alternative hypotheses are two competing claims that researchers weigh evidence for and against using a statistical test :

- Null hypothesis ( H 0 ): There’s no effect in the population .

- Alternative hypothesis ( H a or H 1 ) : There’s an effect in the population.

Table of contents

Answering your research question with hypotheses, what is a null hypothesis, what is an alternative hypothesis, similarities and differences between null and alternative hypotheses, how to write null and alternative hypotheses, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions.

The null and alternative hypotheses offer competing answers to your research question . When the research question asks “Does the independent variable affect the dependent variable?”:

- The null hypothesis ( H 0 ) answers “No, there’s no effect in the population.”

- The alternative hypothesis ( H a ) answers “Yes, there is an effect in the population.”

The null and alternative are always claims about the population. That’s because the goal of hypothesis testing is to make inferences about a population based on a sample . Often, we infer whether there’s an effect in the population by looking at differences between groups or relationships between variables in the sample. It’s critical for your research to write strong hypotheses .

You can use a statistical test to decide whether the evidence favors the null or alternative hypothesis. Each type of statistical test comes with a specific way of phrasing the null and alternative hypothesis. However, the hypotheses can also be phrased in a general way that applies to any test.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

The null hypothesis is the claim that there’s no effect in the population.

If the sample provides enough evidence against the claim that there’s no effect in the population ( p ≤ α), then we can reject the null hypothesis . Otherwise, we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

Although “fail to reject” may sound awkward, it’s the only wording that statisticians accept . Be careful not to say you “prove” or “accept” the null hypothesis.

Null hypotheses often include phrases such as “no effect,” “no difference,” or “no relationship.” When written in mathematical terms, they always include an equality (usually =, but sometimes ≥ or ≤).

You can never know with complete certainty whether there is an effect in the population. Some percentage of the time, your inference about the population will be incorrect. When you incorrectly reject the null hypothesis, it’s called a type I error . When you incorrectly fail to reject it, it’s a type II error.

Examples of null hypotheses

The table below gives examples of research questions and null hypotheses. There’s always more than one way to answer a research question, but these null hypotheses can help you get started.

| ( ) | ||

| Does tooth flossing affect the number of cavities? | Tooth flossing has on the number of cavities. | test: The mean number of cavities per person does not differ between the flossing group (µ ) and the non-flossing group (µ ) in the population; µ = µ . |

| Does the amount of text highlighted in the textbook affect exam scores? | The amount of text highlighted in the textbook has on exam scores. | : There is no relationship between the amount of text highlighted and exam scores in the population; β = 0. |

| Does daily meditation decrease the incidence of depression? | Daily meditation the incidence of depression.* | test: The proportion of people with depression in the daily-meditation group ( ) is greater than or equal to the no-meditation group ( ) in the population; ≥ . |

*Note that some researchers prefer to always write the null hypothesis in terms of “no effect” and “=”. It would be fine to say that daily meditation has no effect on the incidence of depression and p 1 = p 2 .

The alternative hypothesis ( H a ) is the other answer to your research question . It claims that there’s an effect in the population.

Often, your alternative hypothesis is the same as your research hypothesis. In other words, it’s the claim that you expect or hope will be true.

The alternative hypothesis is the complement to the null hypothesis. Null and alternative hypotheses are exhaustive, meaning that together they cover every possible outcome. They are also mutually exclusive, meaning that only one can be true at a time.

Alternative hypotheses often include phrases such as “an effect,” “a difference,” or “a relationship.” When alternative hypotheses are written in mathematical terms, they always include an inequality (usually ≠, but sometimes < or >). As with null hypotheses, there are many acceptable ways to phrase an alternative hypothesis.

Examples of alternative hypotheses

The table below gives examples of research questions and alternative hypotheses to help you get started with formulating your own.

| Does tooth flossing affect the number of cavities? | Tooth flossing has an on the number of cavities. | test: The mean number of cavities per person differs between the flossing group (µ ) and the non-flossing group (µ ) in the population; µ ≠ µ . |

| Does the amount of text highlighted in a textbook affect exam scores? | The amount of text highlighted in the textbook has an on exam scores. | : There is a relationship between the amount of text highlighted and exam scores in the population; β ≠ 0. |

| Does daily meditation decrease the incidence of depression? | Daily meditation the incidence of depression. | test: The proportion of people with depression in the daily-meditation group ( ) is less than the no-meditation group ( ) in the population; < . |

Null and alternative hypotheses are similar in some ways:

- They’re both answers to the research question.

- They both make claims about the population.

- They’re both evaluated by statistical tests.

However, there are important differences between the two types of hypotheses, summarized in the following table.

| A claim that there is in the population. | A claim that there is in the population. | |

|

| ||

| Equality symbol (=, ≥, or ≤) | Inequality symbol (≠, <, or >) | |

| Rejected | Supported | |

| Failed to reject | Not supported |

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

To help you write your hypotheses, you can use the template sentences below. If you know which statistical test you’re going to use, you can use the test-specific template sentences. Otherwise, you can use the general template sentences.

General template sentences

The only thing you need to know to use these general template sentences are your dependent and independent variables. To write your research question, null hypothesis, and alternative hypothesis, fill in the following sentences with your variables:

Does independent variable affect dependent variable ?

- Null hypothesis ( H 0 ): Independent variable does not affect dependent variable.

- Alternative hypothesis ( H a ): Independent variable affects dependent variable.

Test-specific template sentences

Once you know the statistical test you’ll be using, you can write your hypotheses in a more precise and mathematical way specific to the test you chose. The table below provides template sentences for common statistical tests.

| ( ) | ||

| test

with two groups | The mean dependent variable does not differ between group 1 (µ ) and group 2 (µ ) in the population; µ = µ . | The mean dependent variable differs between group 1 (µ ) and group 2 (µ ) in the population; µ ≠ µ . |

| with three groups | The mean dependent variable does not differ between group 1 (µ ), group 2 (µ ), and group 3 (µ ) in the population; µ = µ = µ . | The mean dependent variable of group 1 (µ ), group 2 (µ ), and group 3 (µ ) are not all equal in the population. |

| There is no correlation between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; ρ = 0. | There is a correlation between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; ρ ≠ 0. | |

| There is no relationship between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; β = 0. | There is a relationship between independent variable and dependent variable in the population; β ≠ 0. | |

| Two-proportions test | The dependent variable expressed as a proportion does not differ between group 1 ( ) and group 2 ( ) in the population; = . | The dependent variable expressed as a proportion differs between group 1 ( ) and group 2 ( ) in the population; ≠ . |

Note: The template sentences above assume that you’re performing one-tailed tests . One-tailed tests are appropriate for most studies.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Descriptive statistics

- Measures of central tendency

- Correlation coefficient

Methodology

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Types of interviews

- Cohort study

- Thematic analysis

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Survivorship bias

- Availability heuristic

- Nonresponse bias

- Regression to the mean

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

The null hypothesis is often abbreviated as H 0 . When the null hypothesis is written using mathematical symbols, it always includes an equality symbol (usually =, but sometimes ≥ or ≤).

The alternative hypothesis is often abbreviated as H a or H 1 . When the alternative hypothesis is written using mathematical symbols, it always includes an inequality symbol (usually ≠, but sometimes < or >).

A research hypothesis is your proposed answer to your research question. The research hypothesis usually includes an explanation (“ x affects y because …”).

A statistical hypothesis, on the other hand, is a mathematical statement about a population parameter. Statistical hypotheses always come in pairs: the null and alternative hypotheses . In a well-designed study , the statistical hypotheses correspond logically to the research hypothesis.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Turney, S. (2023, June 22). Null & Alternative Hypotheses | Definitions, Templates & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/statistics/null-and-alternative-hypotheses/

Is this article helpful?

Shaun Turney

Other students also liked, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, hypothesis testing | a step-by-step guide with easy examples, type i & type ii errors | differences, examples, visualizations, what is your plagiarism score.

Directional and non-directional hypothesis: A Comprehensive Guide

Karolina Konopka

Customer support manager

Want to talk with us?

In the world of research and statistical analysis, hypotheses play a crucial role in formulating and testing scientific claims. Understanding the differences between directional and non-directional hypothesis is essential for designing sound experiments and drawing accurate conclusions. Whether you’re a student, researcher, or simply curious about the foundations of hypothesis testing, this guide will equip you with the knowledge and tools to navigate this fundamental aspect of scientific inquiry.

Understanding Directional Hypothesis

Understanding directional hypotheses is crucial for conducting hypothesis-driven research, as they guide the selection of appropriate statistical tests and aid in the interpretation of results. By incorporating directional hypotheses, researchers can make more precise predictions, contribute to scientific knowledge, and advance their fields of study.

Definition of directional hypothesis

Directional hypotheses, also known as one-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that make specific predictions about the direction of a relationship or difference between variables. Unlike non-directional hypotheses, which simply state that there is a relationship or difference without specifying its direction, directional hypotheses provide a focused and precise expectation.

A directional hypothesis predicts either a positive or negative relationship between variables or predicts that one group will perform better than another. It asserts a specific direction of effect or outcome. For example, a directional hypothesis could state that “increased exposure to sunlight will lead to an improvement in mood” or “participants who receive the experimental treatment will exhibit higher levels of cognitive performance compared to the control group.”

Directional hypotheses are formulated based on existing theory, prior research, or logical reasoning, and they guide the researcher’s expectations and analysis. They allow for more targeted predictions and enable researchers to test specific hypotheses using appropriate statistical tests.

The role of directional hypothesis in research

Directional hypotheses also play a significant role in research surveys. Let’s explore their role specifically in the context of survey research:

- Objective-driven surveys : Directional hypotheses help align survey research with specific objectives. By formulating directional hypotheses, researchers can focus on gathering data that directly addresses the predicted relationship or difference between variables of interest.

- Question design and measurement : Directional hypotheses guide the design of survey question types and the selection of appropriate measurement scales. They ensure that the questions are tailored to capture the specific aspects related to the predicted direction, enabling researchers to obtain more targeted and relevant data from survey respondents.

- Data analysis and interpretation : Directional hypotheses assist in data analysis by directing researchers towards appropriate statistical tests and methods. Researchers can analyze the survey data to specifically test the predicted relationship or difference, enhancing the accuracy and reliability of their findings. The results can then be interpreted within the context of the directional hypothesis, providing more meaningful insights.

- Practical implications and decision-making : Directional hypotheses in surveys often have practical implications. When the predicted relationship or difference is confirmed, it informs decision-making processes, program development, or interventions. The survey findings based on directional hypotheses can guide organizations, policymakers, or practitioners in making informed choices to achieve desired outcomes.

- Replication and further research : Directional hypotheses in survey research contribute to the replication and extension of studies. Researchers can replicate the survey with different populations or contexts to assess the generalizability of the predicted relationships. Furthermore, if the directional hypothesis is supported, it encourages further research to explore underlying mechanisms or boundary conditions.

By incorporating directional hypotheses in survey research, researchers can align their objectives, design effective surveys, conduct focused data analysis, and derive practical insights. They provide a framework for organizing survey research and contribute to the accumulation of knowledge in the field.

Examples of research questions for directional hypothesis

Here are some examples of research questions that lend themselves to directional hypotheses:

- Does increased daily exercise lead to a decrease in body weight among sedentary adults?

- Is there a positive relationship between study hours and academic performance among college students?

- Does exposure to violent video games result in an increase in aggressive behavior among adolescents?

- Does the implementation of a mindfulness-based intervention lead to a reduction in stress levels among working professionals?

- Is there a difference in customer satisfaction between Product A and Product B, with Product A expected to have higher satisfaction ratings?

- Does the use of social media influence self-esteem levels, with higher social media usage associated with lower self-esteem?

- Is there a negative relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover, indicating that lower job satisfaction leads to higher turnover rates?

- Does the administration of a specific medication result in a decrease in symptoms among individuals with a particular medical condition?

- Does increased access to early childhood education lead to improved cognitive development in preschool-aged children?

- Is there a difference in purchase intention between advertisements with celebrity endorsements and advertisements without, with celebrity endorsements expected to have a higher impact?

These research questions generate specific predictions about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables and can be tested using appropriate research methods and statistical analyses.

Definition of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses, also known as two-tailed hypotheses, are statements in research that indicate the presence of a relationship or difference between variables without specifying the direction of the effect. Instead of making predictions about the specific direction of the relationship or difference, non-directional hypotheses simply state that there is an association or distinction between the variables of interest.

Non-directional hypotheses are often used when there is no prior theoretical basis or clear expectation about the direction of the relationship. They leave the possibility open for either a positive or negative relationship, or for both groups to differ in some way without specifying which group will perform better or worse.

Advantages and utility of non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses in survey s offer several advantages and utilities, providing flexibility and comprehensive analysis of survey data. Here are some of the key advantages and utilities of using non-directional hypotheses in surveys:

- Exploration of Relationships : Non-directional hypotheses allow researchers to explore and examine relationships between variables without assuming a specific direction. This is particularly useful in surveys where the relationship between variables may not be well-known or there may be conflicting evidence regarding the direction of the effect.

- Flexibility in Question Design : With non-directional hypotheses, survey questions can be designed to measure the relationship between variables without being biased towards a particular outcome. This flexibility allows researchers to collect data and analyze the results more objectively.

- Open to Unexpected Findings : Non-directional hypotheses enable researchers to be open to unexpected or surprising findings in survey data. By not committing to a specific direction of the effect, researchers can identify and explore relationships that may not have been initially anticipated, leading to new insights and discoveries.

- Comprehensive Analysis : Non-directional hypotheses promote comprehensive analysis of survey data by considering the possibility of an effect in either direction. Researchers can assess the magnitude and significance of relationships without limiting their analysis to only one possible outcome.

- S tatistical Validity : Non-directional hypotheses in surveys allow for the use of two-tailed statistical tests, which provide a more conservative and robust assessment of significance. Two-tailed tests consider both positive and negative deviations from the null hypothesis, ensuring accurate and reliable statistical analysis of survey data.

- Exploratory Research : Non-directional hypotheses are particularly useful in exploratory research, where the goal is to gather initial insights and generate hypotheses. Surveys with non-directional hypotheses can help researchers explore various relationships and identify patterns that can guide further research or hypothesis development.

It is worth noting that the choice between directional and non-directional hypotheses in surveys depends on the research objectives, existing knowledge, and the specific variables being investigated. Researchers should carefully consider the advantages and limitations of each approach and select the one that aligns best with their research goals and survey design.

- Share with others

- Twitter Twitter Icon

- LinkedIn LinkedIn Icon

Related posts

Mastering matrix questions: the complete guide + one special technique, microsurveys: complete guide, recurring surveys: the ultimate guide, close-ended questions: definition, types, and examples, top 10 typeform alternatives and competitors, 15 best google forms alternatives and competitors, get answers today.

- No credit card required

- No time limit on Free plan

You can modify this template in every possible way.

All templates work great on every device.

What is a Directional Hypothesis? (Definition & Examples)

A statistical hypothesis is an assumption about a population parameter . For example, we may assume that the mean height of a male in the U.S. is 70 inches.

The assumption about the height is the statistical hypothesis and the true mean height of a male in the U.S. is the population parameter .

To test whether a statistical hypothesis about a population parameter is true, we obtain a random sample from the population and perform a hypothesis test on the sample data.

Whenever we perform a hypothesis test, we always write down a null and alternative hypothesis:

- Null Hypothesis (H 0 ): The sample data occurs purely from chance.

- Alternative Hypothesis (H A ): The sample data is influenced by some non-random cause.

A hypothesis test can either contain a directional hypothesis or a non-directional hypothesis:

- Directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the less than (“”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is a positive or negative effect.

- Non-directional hypothesis: The alternative hypothesis contains the not equal (“≠”) sign. This indicates that we’re testing whether or not there is some effect, without specifying the direction of the effect.

Note that directional hypothesis tests are also called “one-tailed” tests and non-directional hypothesis tests are also called “two-tailed” tests.

Check out the following examples to gain a better understanding of directional vs. non-directional hypothesis tests.

Example 1: Baseball Programs

A baseball coach believes a certain 4-week program will increase the mean hitting percentage of his players, which is currently 0.285.

To test this, he measures the hitting percentage of each of his players before and after participating in the program.

He then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = .285 (the program will have no effect on the mean hitting percentage)

- H A : μ > .285 (the program will cause mean hitting percentage to increase)

This is an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the greater than “>” sign. The coach believes that the program will influence the mean hitting percentage of his players in a positive direction.

Example 2: Plant Growth

A biologist believes that a certain pesticide will cause plants to grow less during a one-month period than they normally do, which is currently 10 inches.

To test this, she applies the pesticide to each of the plants in her laboratory for one month.

She then performs a hypothesis test using the following hypotheses:

- H 0 : μ = 10 inches (the pesticide will have no effect on the mean plant growth)

This is also an example of a directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the less than “negative direction.

Example 3: Studying Technique

A professor believes that a certain studying technique will influence the mean score that her students receive on a certain exam, but she’s unsure if it will increase or decrease the mean score, which is currently 82.

To test this, she lets each student use the studying technique for one month leading up to the exam and then administers the same exam to each of the students.

- H 0 : μ = 82 (the studying technique will have no effect on the mean exam score)

- H A : μ ≠ 82 (the studying technique will cause the mean exam score to be different than 82)

This is an example of a non-directional hypothesis because the alternative hypothesis contains the not equal “≠” sign. The professor believes that the studying technique will influence the mean exam score, but doesn’t specify whether it will cause the mean score to increase or decrease.

Additional Resources

Introduction to Hypothesis Testing Introduction to the One Sample t-test Introduction to the Two Sample t-test Introduction to the Paired Samples t-test

How to Perform a Partial F-Test in Excel

4 examples of confidence intervals in real life, related posts, how to normalize data between -1 and 1, vba: how to check if string contains another..., how to interpret f-values in a two-way anova, how to create a vector of ones in..., how to find the mode of a histogram..., how to find quartiles in even and odd..., how to determine if a probability distribution is..., what is a symmetric histogram (definition & examples), how to calculate sxy in statistics (with example), how to calculate sxx in statistics (with example).

How to Write a Directional Hypothesis: A Step-by-Step Guide

In research, hypotheses play a crucial role in guiding investigations and making predictions about relationships between variables.

In this blog post, we’ll explore what a directional hypothesis is, why it’s important, and provide a step-by-step guide on how to write one effectively.

What is a Directional Hypothesis?

Examples of directional hypotheses, why to write a directional hypothesis.

Directional hypotheses offer several advantages in research. They provide researchers with a more focused prediction, allowing them to test specific hypotheses rather than exploring all possible relationships between variables.

Step 1: Identify the Variables

Step 2: predict the direction.

Based on your understanding of the relationship between the variables, predict the direction of the effect.

Step 3: Use Clear Language

Write your directional hypothesis using clear and concise language. Avoid technical jargon or terms that may be difficult for readers to understand. Your hypothesis should be easily understood by both researchers and non-experts.

Step 4: Ensure Testability

Step 5: revise and refine.

Writing a directional hypothesis is an essential skill for researchers conducting experiments and investigations.

Whether you’re a researcher or just starting out in the field, mastering the art of writing directional hypotheses will enhance the quality and rigor of your research endeavors.

Related Posts

Types of research questions, 8 types of validity in research | examples, operationalization of variables in research | examples | benefits, 10 types of variables in research: definitions and examples, what is a theoretical framework examples, types of reliability in research | example | ppt, independent vs. dependent variable, 4 research proposal examples | proposal sample, how to write a literature review in research: a step-by-step guide, how to write an abstract for a research paper.

Tools, Technologies and Training for Healthcare Laboratories

- Z-Stats / Basic Statistics

Z-8: Two-Sample and Directional Hypothesis Testing

This lesson describes some refinements to the hypothesis testing approach that was introduced in the previous lesson. The truth of the matter is that the previous lesson was somewhat oversimplified in order to focus on the concept and general steps in the hypothesis testing procedure. With that background, we can now get into some of the finer points of hypothesis testing.

EdD, Assistant Professor Clinical Laboratory Science Program, University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky October 1999

Refinements in calculations, refinements in procedure, a two-tailed test for our mice, a one-tailed test for our mice.

- Critical t-values for one-tailed and two-tailed tests

- About the Author

Two sample case

The "two sample case" is a special case in which the difference between two sample means is examined. This sounds like what we did in the last lesson, but we actually looked at the difference between an observed or sample group mean and a control group mean, which was treated as if it were a population mean (rather than an observed or sample mean). There are some fine points that need to be considered about the calculations and the procedure.

Mathematically, there are some differences in the formula that should be used. Recall the form of the equation for calculating a t-value:

where Xbar is the mean of the experimental group, and µ is a population parameter or the mean of the population. In the last lesson, we substituted the control group mean XbarB for µ. However, the control group was actually a sample from the population of all such mice (in this example) and following suit, the experimental group was also just a sample from its population. Phrasing the situation this way, there are now two sets of differences that must be considered: the difference between sample means or XbarA-XbarB and the difference between population means from which these samples came or µA-µB. Those expressions should be substituted into the t calc formula to give the proper mathematical form:

- In this new equation, the difference between means (Xbar A - XbarB) is called bias and is important in determining test accuracy, so even though this discussion is getting more complicated, the statistic that we are deriving is very important.

- When the square root is taken, the result is called the standard deviation of the difference between means , SDd , which is shown by the formula:

- The proper equation for calculating the t-value for the two-sample case then becomes:

Remember the steps for testing a hypothesis are: (1) State the hypotheses; (2) Set the criterion for rejection of Ho; (3) Compute the test statistic; (4) Decide about Ho.

- The null hypothesis can be stated as: Ho: µA = µB or µA - µB = 0. But it may be more revealing to say Ho: (XbarA-XbarB) - (µA - µB) = 0. The difference between the sample means minus the difference between the population means equals zero.

- The alternative hypothesis can be stated as: Ha: µA is not equal to µB or Ha: (XbarA-XbarB) - (µA - µB) is not equal to 0, i.e., the means of the two groups are not equal.

- The criteria for rejection or the alpha level is 0.05.

- The test statistic is computed as:

- Since it is hypothesized that the two methods are comparable and the difference between the means of the two populations is zero (µA - µB = 0), the calculation can be simplified as follows:

- If this t calc is greater than 1.96 then the null hypothesis of no difference can be overturned (p0.05).

- Even though we have used several different mathematical formulae, the interpretations are the same as before.

Directional hypothesis testing vs non-directional testing

Remember the example of testing the effect of antibiotics on mice in Lesson 7. The point of the study was to find out if the mice who were treated with the antibiotic would outlive those who were not treated (i.e., the control group). Are you surprised that the researcher did not hypothesize that the control group might outlive the treatment group? Would it make any difference in how the hypothesis testing were carried out? These questions raise the issue of directional testing, or one-tailed vs two-tailed tests.

The issue of two-side vs one-side tests becomes important when selecting the critical t-value. In the earlier discussion of this example, the alpha level was set to 0.05, but that 0.05 was actually divided equally between the left and right tails of the distribution curve. The condition being tested is that group A has a "different" life span as compared to group B, which represents a two-tailed test as illustrated in Figure 8-2.

Critical t-values for one-tailed and two tailed tests

This can be confusing and it should be helpful to think about having one or two gates on the curve. For example, for an alpha level of 0.05 and a two-tail test, there are two gates - one at -1.96 and one at +1.96. If you "walk" out of either of those gates, then you have demonstrated significance at p=0.05 or less. For a one-tail test, there is only one gate at +1.65. If you "walk" out of this gate, you have demonstrated significance at p=0.05 or less.

To reiterate, if you are standing right at the gate (1.96) for a two-tail test, then you have just barely met the p=0.05 requirement. However, if you are standing at the 1.96 point when running a one-tail test, then you have already exceeded the 1.65 gate and the probability must be even more significant, say p=0.025. It's important to find the critical t-value that is correct for the intended directional nature of the test.

About the author: Madelon F. Zady

Madelon F. Zady is an Assistant Professor at the University of Louisville, School of Allied Health Sciences Clinical Laboratory Science program and has over 30 years experience in teaching. She holds BS, MAT and EdD degrees from the University of Louisville, has taken other advanced course work from the School of Medicine and School of Education, and also advanced courses in statistics. She is a registered MT(ASCP) and a credentialed CLS(NCA) and has worked part-time as a bench technologist for 14 years. She is a member of the: American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science, Kentucky State Society for Clinical Laboratory Science, American Educational Research Association, and the National Science Teachers Association. Her teaching areas are clinical chemistry and statistics. Her research areas are metacognition and learning theory.

- "Westgard Rules"

- Basic QC Practices

- High Reliability

- "Housekeeping"

- Maryland General

- Method Validation

- Quality Requirements and Standards

- Quality of Laboratory Testing

- Guest Essay

- Risk Management

- Sigma Metric Analysis

- Quality Standards

- Basic Planning for Quality

- Basic Method Validation

- Quality Management

- Advanced Quality Management / Six Sigma

- Patient Safety Concepts

- Quality Requirements

- CLIA Final Rule

- Course Orders

- Feedback Form

Directional vs Non-Directional Hypothesis: Key Difference

In statistics, a directional hypothesis, also known as a one-tailed hypothesis, is a type of hypothesis that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables or the direction of the difference between groups.

The introduction of a directional hypothesis in a research study provides an overview of the specific prediction being made about the relationship between variables or the difference between groups. It sets the stage for the research question and outlines the expected direction of the findings. The introduction typically includes the following elements:

Research Context: Begin by introducing the general topic or research area that the study is focused on. Provide background information and highlight the significance of the research question.

Research Question: Clearly state the specific research question that the study aims to answer. This question should be directly related to the variables being investigated.

Previous Research: Summarize relevant literature or previous studies that have explored similar or related topics. This helps establish the existing knowledge base and provides a rationale for the hypothesis.

Hypothesis Statement: Present the directional hypothesis clearly and concisely. State the predicted relationship between variables or the expected difference between groups. For example, if studying the impact of a new teaching method on student performance, a directional hypothesis could be, “Students who receive the new teaching method will demonstrate higher test scores compared to students who receive the traditional teaching method.”

Justification: Provide a logical explanation for the directional hypothesis based on the existing literature or theoretical framework . Discuss any previous findings, theories, or empirical evidence that support the predicted direction of the relationship or difference.

Objectives: Outline the specific objectives or aims of the study, which should align with the research question and hypothesis. These objectives help guide the research process and provide a clear focus for the study.

By including these elements in the introduction of a research study, the directional hypothesis is introduced effectively, providing a clear and justified prediction about the expected outcome of the research.

When formulating a directional hypothesis, researchers make a specific prediction about the expected relationship or difference between variables. They specify whether they expect an increase or decrease in the dependent variable, or whether one group will score higher or lower than another group

What is Directional Hypothesis?

With a correlational study, a directional hypothesis states that there is a positive (or negative) correlation between two variables. When a hypothesis states the direction of the results, it is referred to as a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis; this is because it states that the results go in one direction.

Definition:

A directional hypothesis is a one-tailed hypothesis that states the direction of the difference or relationship (e.g. boys are more helpful than girls).

Research Question: Does exercise have a positive impact on mood?

Directional Hypothesis: Engaging in regular exercise will result in an increase in positive mood compared to a sedentary lifestyle.

In this example, the directional hypothesis predicts that regular exercise will have a specific effect on mood, specifically leading to an increase in positive mood. The researcher expects that individuals who engage in regular exercise will experience improvements in their overall mood compared to individuals who lead a sedentary lifestyle.

It’s important to note that this is just one example, and directional hypotheses can be formulated in various research areas and contexts. The key is to make a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables based on prior knowledge or theoretical considerations.

Advantages of Directional Hypothesis

There are several advantages to using a directional hypothesis in research studies. Here are a few key benefits:

Specific Prediction:

A directional hypothesis allows researchers to make a specific prediction about the expected relationship or difference between variables. This provides a clear focus for the study and helps guide the research process. It also allows for more precise interpretation of the results.

Testable and Refutable:

Directional hypotheses can be tested and either supported or refuted by empirical evidence. Researchers can design their study and select appropriate statistical tests to specifically examine the predicted direction of the relationship or difference. This enhances the rigor and validity of the research.

Efficiency and Resource Allocation:

By making a specific prediction, researchers can allocate their resources more efficiently. They can focus on collecting data and conducting analyses that directly test the directional hypothesis, rather than exploring all possible directions or relationships. This can save time, effort, and resources.

Theory Development:

Directional hypotheses contribute to the development of theories and scientific knowledge. When a directional hypothesis is supported by empirical evidence, it provides support for existing theories or helps generate new theories. This advancement in knowledge can guide future research and understanding in the field.

Practical Applications:

Directional hypotheses can have practical implications and applications. If a hypothesis predicts a specific direction of change, such as the effectiveness of a treatment or intervention, it can inform decision-making and guide practical applications in fields such as medicine, psychology, or education.

Enhanced Communication:

Directional hypotheses facilitate clearer communication of research findings. When researchers have made specific predictions about the direction of the relationship or difference, they can effectively communicate their results to both academic and non-academic audiences. This promotes better understanding and application of the research outcomes.

It’s important to note that while directional hypotheses offer advantages, they also require stronger evidence to support them compared to non-directional hypotheses. Researchers should carefully consider the research context, existing literature, and theoretical considerations before formulating a directional hypothesis.

Disadvantages of Directional Hypothesis

While directional hypotheses have their advantages, there are also some potential disadvantages to consider:

Risk of Type I Error:

Directional hypotheses increase the risk of committing a Type I error , also known as a false positive. By focusing on a specific predicted direction, researchers may overlook the possibility of an opposite or null effect. If the actual relationship or difference does not align with the predicted direction, researchers may incorrectly conclude that there is no effect when, in fact, there may be.

Narrow Focus:

Directional hypotheses restrict the scope of investigation to a specific predicted direction. This narrow focus may overlook other potential relationships, nuances, or alternative explanations. Researchers may miss valuable insights or unexpected findings by excluding other possibilities from consideration.

Limited Generalizability:

Directional hypotheses may limit the generalizability of findings. If the study supports the predicted direction, the results may only apply to the specific context and conditions outlined in the hypothesis. Generalizing the findings to different populations, settings, or variables may require further research.

Biased Interpretation:

Directional hypotheses can introduce bias in the interpretation of results. Researchers may be inclined to selectively focus on evidence that supports the predicted direction while downplaying or ignoring contradictory evidence. This can hinder objectivity and lead to biased conclusions.

Increased Sample Size Requirements:

Directional hypotheses often require larger sample sizes compared to non-directional hypotheses. This is because statistical power needs to be sufficient to detect the predicted direction with a reasonable level of confidence. Larger samples can be more time-consuming and resource-intensive to obtain.

Reduced Flexibility:

Directional hypotheses limit flexibility in data analysis and statistical testing. Researchers may feel compelled to use specific statistical tests or analytical approaches that align with the predicted direction, potentially overlooking alternative methods that may be more appropriate or informative.

It’s important to weigh these disadvantages against the specific research context and objectives when deciding whether to use a directional hypothesis. In some cases, a non-directional hypothesis may be more suitable, allowing for a more exploratory and comprehensive investigation of the research question.

Non-Directional Hypothesis:

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, is a type of hypothesis that does not specify the direction of the relationship between variables or the difference between groups. Instead of predicting a specific direction, a non-directional hypothesis suggests that there will be a significant relationship or difference, without indicating whether it will be positive or negative, higher or lower, etc.

The introduction of a non-directional hypothesis in a research study provides an overview of the general prediction being made about the relationship between variables or the difference between groups, without specifying the direction. It sets the stage for the research question and outlines the expectation of a significant relationship or difference. The introduction typically includes the following elements:

Research Context:

Begin by introducing the general topic or research area that the study is focused on. Provide background information and highlight the significance of the research question.

Research Question:

Clearly state the specific research question that the study aims to answer. This question should be directly related to the variables being investigated.

Previous Research:

Summarize relevant literature or previous studies that have explored similar or related topics. This helps establish the existing knowledge base and provides a rationale for the hypothesis.

Hypothesis Statement:

Present the non-directional hypothesis clearly and concisely. State that there is an expected relationship or difference between variables or groups without specifying the direction. For example, if studying the relationship between socioeconomic status and academic achievement, a non-directional hypothesis could be, “There is a significant relationship between socioeconomic status and academic achievement.”

Justification:

Provide a logical explanation for the non-directional hypothesis based on the existing literature or theoretical framework. Discuss any previous findings, theories, or empirical evidence that support the notion of a relationship or difference between the variables or groups.

Objectives:

Outline the specific objectives or aims of the study, which should align with the research question and hypothesis. These objectives help guide the research process and provide a clear focus for the study.

By including these elements in the introduction of a research study, the non-directional hypothesis is introduced effectively, indicating the expectation of a significant relationship or difference without specifying the direction

What is Non-directional hypothesis?

In a non-directional hypothesis, researchers acknowledge that there may be an effect or relationship between variables but do not make a specific prediction about the direction of that effect. This allows for a more exploratory approach to data analysis and interpretation

If a hypothesis does not state a direction but simply says that one factor affects another, or that there is an association or correlation between two variables then it is called a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

Research Question: Is there a relationship between social media usage and self-esteem ?

Non-Directional Hypothesis: There is a significant relationship between social media usage and self-esteem.

In this example, the non-directional hypothesis suggests that there is a relationship between social media usage and self-esteem without specifying whether higher social media usage is associated with higher or lower self-esteem. The hypothesis acknowledges the possibility of an effect but does not make a specific prediction about the direction of that effect.

It’s important to note that this is just one example, and non-directional hypotheses can be formulated in various research areas and contexts. The key is to indicate the expectation of a significant relationship or difference without specifying the direction, allowing for a more exploratory approach to data analysis and interpretation.

Advantages of Non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses, also known as two-tailed hypotheses, offer several advantages in research studies. Here are some of the key advantages:

Flexibility in Data Analysis:

Non-directional hypotheses allow for flexibility in data analysis. Researchers are not constrained by a specific predicted direction and can explore the relationship or difference in various ways. This flexibility enables a more comprehensive examination of the data, considering both positive and negative associations or differences.

Objective and Open-Minded Approach:

Non-directional hypotheses promote an objective and open-minded approach to research. Researchers do not have preconceived notions about the direction of the relationship or difference, which helps mitigate biases in data interpretation. They can objectively analyze the data without being influenced by their initial expectations.

Comprehensive Understanding:

By not specifying the direction, non-directional hypotheses facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the relationship or difference being investigated. Researchers can explore and consider all possible outcomes, leading to a more nuanced interpretation of the findings. This broader perspective can provide deeper insights into the research question.

Greater Sensitivity:

Non-directional hypotheses can be more sensitive to detecting unexpected or surprising relationships or differences. Researchers are not solely focused on confirming a specific predicted direction, but rather on uncovering any significant association or difference. This increased sensitivity allows for the identification of novel patterns and relationships that may have been overlooked with a directional hypothesis.

Replication and Generalizability:

Non-directional hypotheses support replication studies and enhance the generalizability of findings. By not restricting the investigation to a specific predicted direction, the results can be more applicable to different populations, contexts, or conditions. This broader applicability strengthens the validity and reliability of the research.

Hypothesis Generation:

Non-directional hypotheses can serve as a foundation for generating new hypotheses and research questions. Significant findings without a specific predicted direction can lead to further investigations and the formulation of more focused directional hypotheses in subsequent studies.

It’s important to consider the specific research context and objectives when deciding between a directional or non-directional hypothesis. Non-directional hypotheses are particularly useful when researchers are exploring new areas or when there is limited existing knowledge about the relationship or difference being studied.

Disadvantages of Non-directional hypothesis

Non-directional hypotheses have their advantages, there are also some potential disadvantages to consider:

Lack of Specificity: Non-directional hypotheses do not provide a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables. This lack of specificity may limit the interpretability and practical implications of the findings. Stakeholders may desire clear guidance on the expected direction of the effect.

Non-directional hypotheses often require larger sample sizes compared to directional hypotheses. This is because statistical power needs to be sufficient to detect any significant relationship or difference, regardless of the direction. Obtaining larger samples can be more time-consuming, resource-intensive, and costly.

Reduced Precision:

By not specifying the direction, non-directional hypotheses may result in less precise findings. Researchers may obtain statistically significant results indicating a relationship or difference, but the lack of direction may hinder their ability to understand the practical implications or mechanism behind the effect.

Potential for Post-hoc Interpretation:

Non-directional hypotheses can increase the risk of post-hoc interpretation of results. Researchers may be tempted to selectively interpret and highlight only the significant findings that support their preconceived notions or expectations, leading to biased interpretations.

Limited Theoretical Guidance:

Non-directional hypotheses may lack theoretical guidance in terms of understanding the underlying mechanisms or causal pathways. Without a specific predicted direction, it can be challenging to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework to explain the relationship or difference being studied.

Potential Missed Opportunities:

Non-directional hypotheses may limit the exploration of specific directions or subgroups within the data. By not focusing on a specific direction, researchers may miss important nuances or interactions that could contribute to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

It’s important to carefully consider the research question, available literature, and research objectives when deciding whether to use a non-directional hypothesis. Depending on the context and goals of the study, a non-directional hypothesis may be appropriate, but researchers should also be aware of the potential limitations and address them accordingly in their research design and interpretation of results.

Difference between directional and non-directional hypothesis

the main difference between a directional hypothesis and a non-directional hypothesis lies in the specificity of the prediction made about the relationship between variables or the difference between groups.

Directional Hypothesis:

A directional hypothesis, also known as a one-tailed hypothesis, makes a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference. It states the expected outcome, whether it is a positive or negative relationship, a higher or lower value, an increase or decrease, etc. The directional hypothesis guides the research in a focused manner, specifying the direction to be tested.

Example: “Students who receive tutoring will demonstrate higher test scores compared to students who do not receive tutoring.”

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, does not specify the direction of the relationship or difference. It acknowledges the possibility of a relationship or difference between variables without predicting a specific direction. The non-directional hypothesis allows for exploration and analysis of both positive and negative associations or differences.

Example: “There is a significant relationship between sleep quality and academic performance.”

In summary, a directional hypothesis makes a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference, while a non-directional hypothesis suggests a relationship or difference without specifying the direction. The choice between the two depends on the research question, existing literature, and the researcher’s objectives. Directional hypotheses provide a focused prediction, while non-directional hypotheses allow for more exploratory analysis .

When to use Directional Hypothesis?

A directional hypothesis is appropriate to use in specific situations where researchers have a clear theoretical or empirical basis for predicting the direction of the relationship or difference between variables. Here are some scenarios where a directional hypothesis is commonly employed:

Prior Research and Theoretical Framework: When previous studies, existing theories, or established empirical evidence strongly suggest a specific direction of the relationship or difference, a directional hypothesis can be formulated. Researchers can build upon the existing knowledge base and make a focused prediction based on this prior information.

Cause-and-Effect Relationships: In studies aiming to establish cause-and-effect relationships, directional hypotheses are often used. When there is a clear theoretical understanding of the causal relationship between variables, researchers can predict the expected direction of the effect based on the proposed mechanism.

Specific Research Objectives: If the research study has specific objectives that require a clear prediction about the direction, a directional hypothesis can be appropriate. For instance, if the aim is to test the effectiveness of a particular intervention or treatment, a directional hypothesis can guide the evaluation by predicting the expected positive or negative outcome.

Practical Applications: Directional hypotheses are useful when the research findings have direct practical implications. For example, in fields such as medicine, psychology, or education, researchers may formulate directional hypotheses to predict the effects of certain interventions or treatments on patient outcomes or educational achievement.

Hypothesis-Testing Approach: Researchers who adopt a hypothesis-testing approach, where they aim to confirm or disconfirm specific predictions, often use directional hypotheses. This approach involves formulating a specific hypothesis and conducting statistical tests to determine whether the data support or refute the predicted direction of the relationship or difference.

When to use non directional hypothesis?

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, is appropriate to use in several situations where researchers do not have a specific prediction about the direction of the relationship or difference between variables. Here are some scenarios where a non-directional hypothesis is commonly employed:

Exploratory Research:

When the research aims to explore a new area or investigate a relationship that has limited prior research or theoretical guidance, a non-directional hypothesis is often used. It allows researchers to gather initial data and insights without being constrained by a specific predicted direction.

Preliminary Studies:

Non-directional hypotheses are useful in preliminary or pilot studies that seek to gather preliminary evidence and generate hypotheses for further investigation. By using a non-directional hypothesis, researchers can gather initial data to inform the development of more specific hypotheses in subsequent studies.

Neutral Expectations:

If researchers have no theoretical or empirical basis to predict the direction of the relationship or difference, a non-directional hypothesis is appropriate. This may occur in situations where there is a lack of prior research, conflicting findings, or inconclusive evidence to support a specific direction.

Comparative Studies:

In studies where the objective is to compare two or more groups or conditions, a non-directional hypothesis is commonly used. The focus is on determining whether a significant difference exists, without making specific predictions about which group or condition will have higher or lower values.

Data-Driven Approach:

When researchers adopt a data-driven or exploratory approach to analysis, non-directional hypotheses are preferred. Instead of testing specific predictions, the aim is to explore the data, identify patterns, and generate hypotheses based on the observed relationships or differences.

Hypothesis-Generating Studies:

Non-directional hypotheses are often used in studies aimed at generating new hypotheses and research questions. By exploring associations or differences without specifying the direction, researchers can identify potential relationships or factors that can serve as a basis for future research.

Strategies to improve directional and non-directional hypothesis

To improve the quality of both directional and non-directional hypotheses, researchers can employ various strategies. Here are some strategies to enhance the formulation of hypotheses:

Strategies to Improve Directional Hypotheses:

Review existing literature:.

Conduct a thorough review of relevant literature to identify previous research findings, theories, and empirical evidence related to the variables of interest. This will help inform and support the formulation of a specific directional hypothesis based on existing knowledge.

Develop a Theoretical Framework:

Build a theoretical framework that outlines the expected causal relationship between variables. The theoretical framework should provide a clear rationale for predicting the direction of the relationship based on established theories or concepts.

Conduct Pilot Studies:

Conducting pilot studies or preliminary research can provide valuable insights and data to inform the formulation of a directional hypothesis. Initial findings can help researchers identify patterns or relationships that support a specific predicted direction.

Seek Expert Input:

Seek input from experts or colleagues in the field who have expertise in the area of study. Discuss the research question and hypothesis with them to obtain valuable insights, perspectives, and feedback that can help refine and improve the directional hypothesis.

Clearly Define Variables:

Clearly define and operationalize the variables in the hypothesis to ensure precision and clarity. This will help avoid ambiguity and ensure that the hypothesis is testable and measurable.

Strategies to Improve Non-Directional Hypotheses:

Preliminary exploration:.

Conduct initial exploratory research to gather preliminary data and insights on the relationship or difference between variables. This can provide a foundation for formulating a non-directional hypothesis based on observed patterns or trends.

Analyze Existing Data:

Analyze existing datasets to identify potential relationships or differences. Exploratory data analysis techniques such as data visualization, descriptive statistics, and correlation analysis can help uncover initial insights that can guide the formulation of a non-directional hypothesis.

Use Exploratory Research Designs:

Employ exploratory research designs such as qualitative studies, case studies, or grounded theory approaches. These designs allow researchers to gather rich data and explore relationships or differences without preconceived notions about the direction.

Consider Alternative Explanations:

When formulating a non-directional hypothesis, consider alternative explanations or potential factors that may influence the relationship or difference between variables. This can help ensure a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the phenomenon under investigation.

Refine Based on Initial Findings: